The Pons

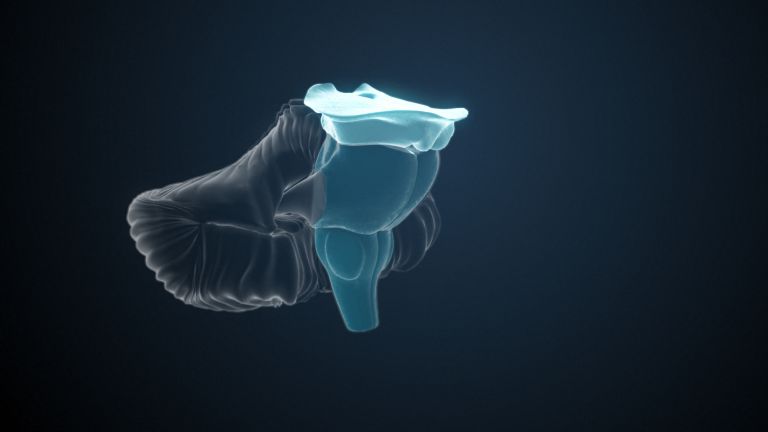

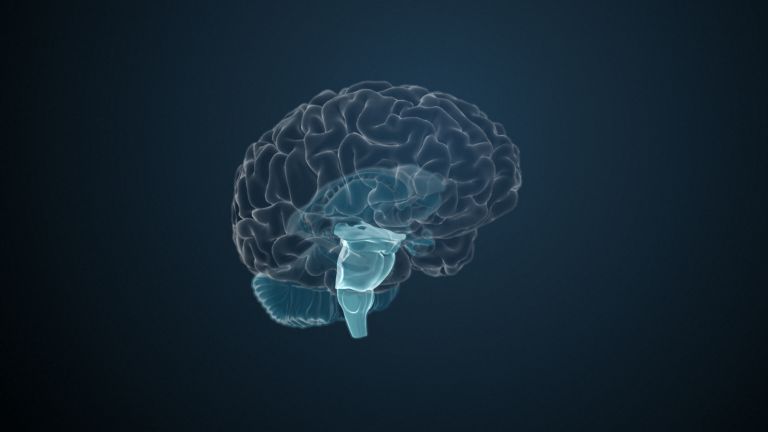

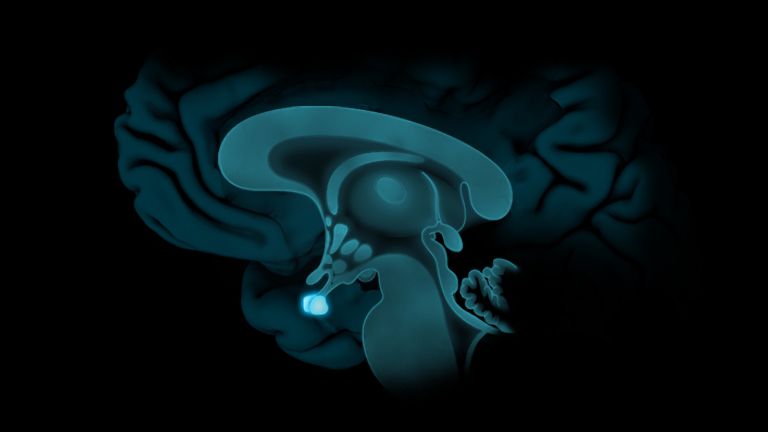

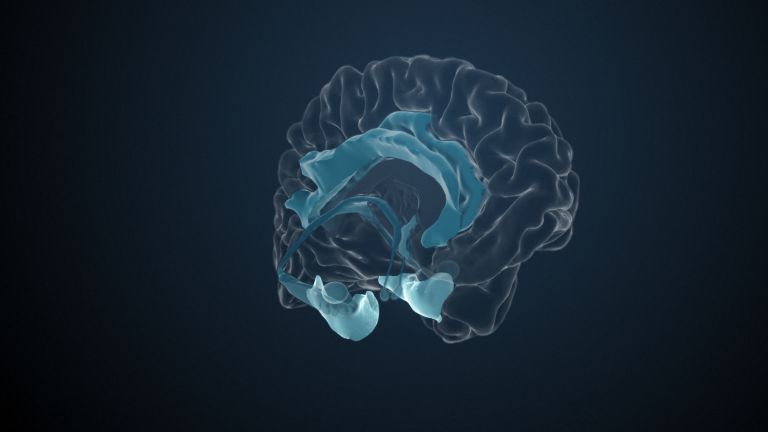

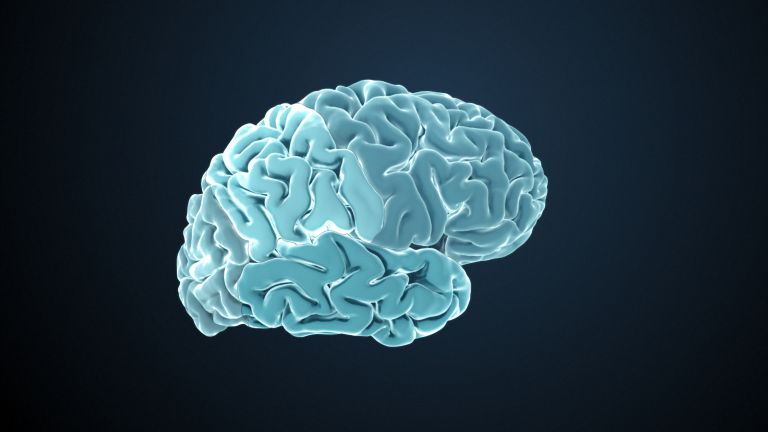

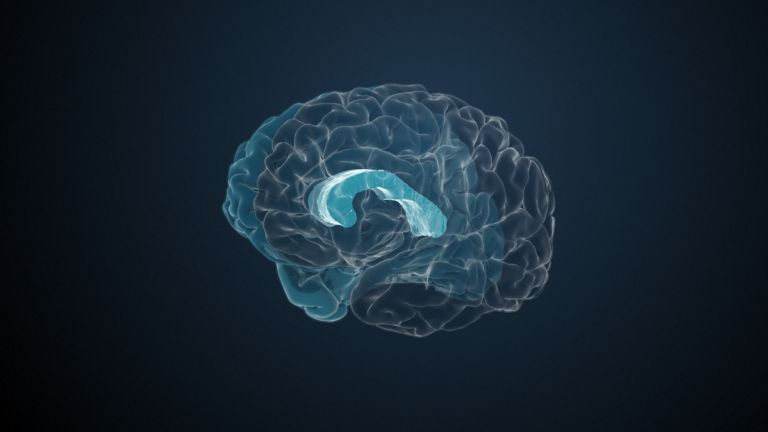

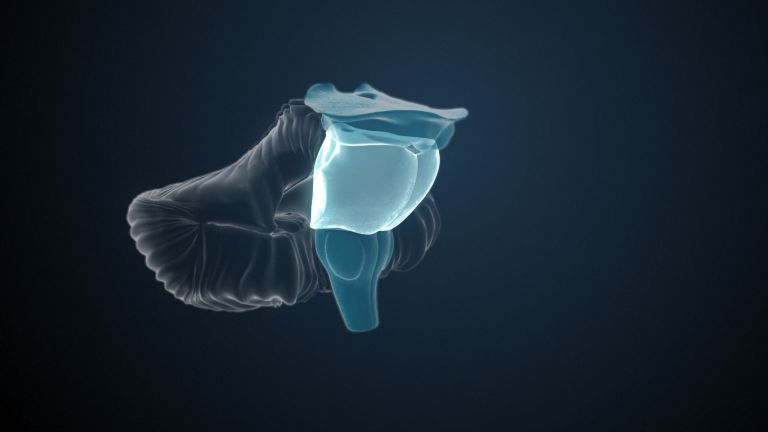

In the middle of the brain stem, a thick bulge protrudes forward, clearly visible: the pons, or bridge in Latin. It gives this section of the brain stem its name. Below it is the medulla oblongata, and above it is the midbrain (mesencephalon).

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Hans-Dieter Hofmann, Prof. Dr. Andreas Vlachos

Published: 20.09.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

- The Pons is a central switching point between the Cerebrum and the cerebellum.

- It plays a key role in controlling movement.

- At the same time, numerous ascending and descending pathways run through it, making the pons an important hub in the entire nervous system.

- In addition, it is part of the network that controls vital vegetative functions – in particular, respiration, the heart, and circulation.

Pons

pons

Area in the brain stem between the medulla oblongata and the mesencephalon. It acts as a switching station for many nerve pathways between the brain and spinal cord and contains numerous nuclei, including cranial nerves and those involved in controlling motor function in cooperation with the cerebellum.

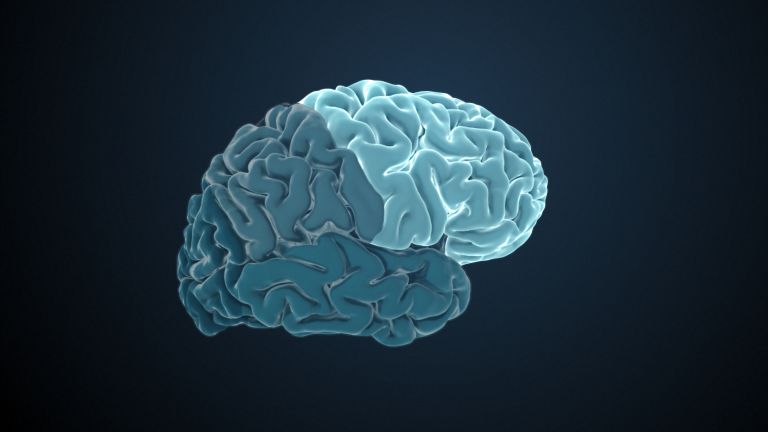

Cerebrum

telencephalon

The cerebrum comprises the cerebral cortex (gray matter), the nerve fibers (white matter), and the basal ganglia. It is the largest part of the brain. The cortex can be divided into four cortical areas: the temporal lobe, frontal lobe, occipital lobe, and parietal lobe.

Its functions include the coordination of perception, motivation, learning, and thinking.

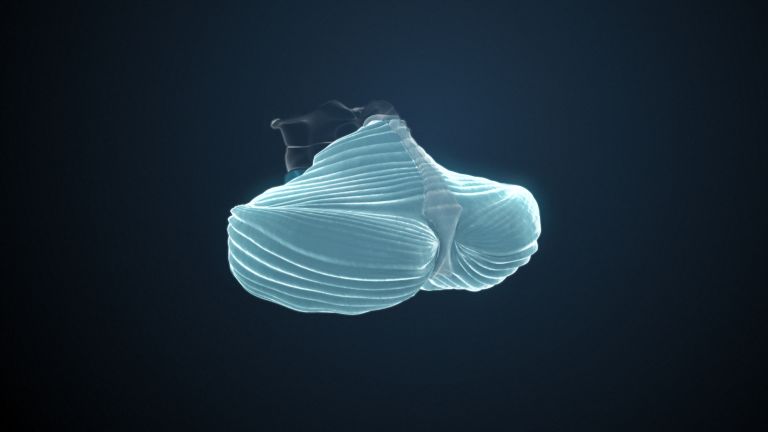

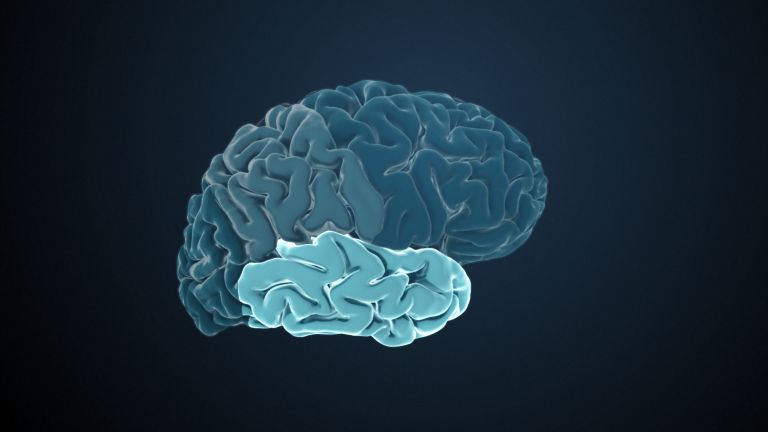

Cerebellum

Cerebellum

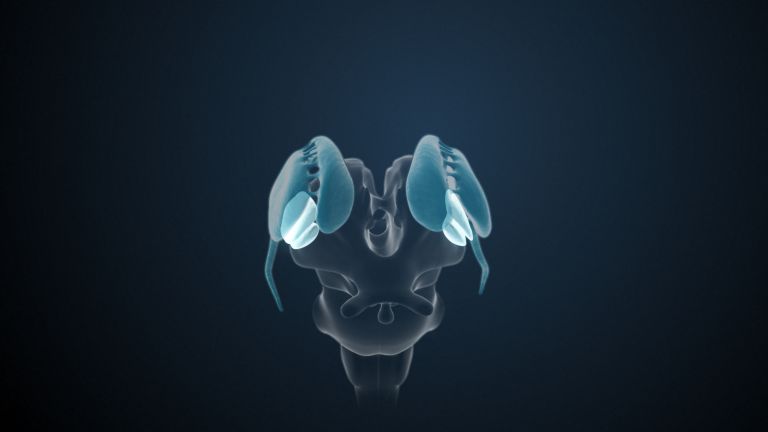

The cerebellum is an important part of the brain, located at the back of the brain stem and below the occipital lobe. It consists of two cerebellar hemispheres covered by the cerebellar cortex and plays an important role in motor processes, among other things. It develops from the rhombencephalon.

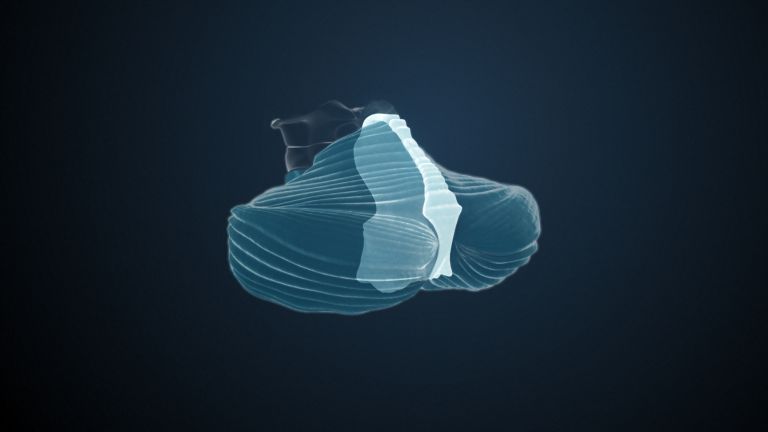

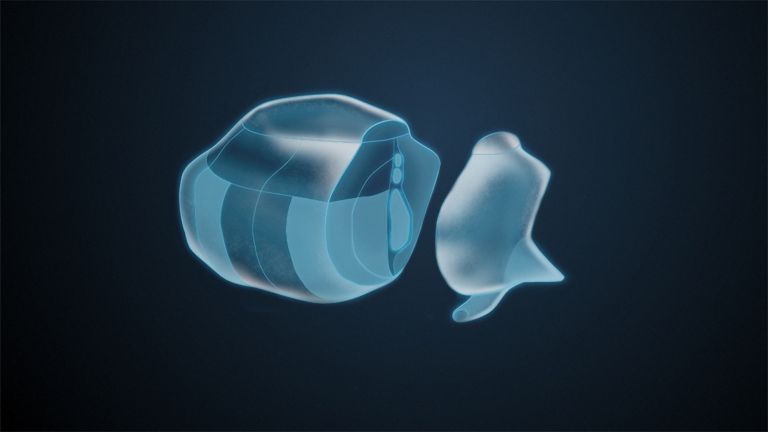

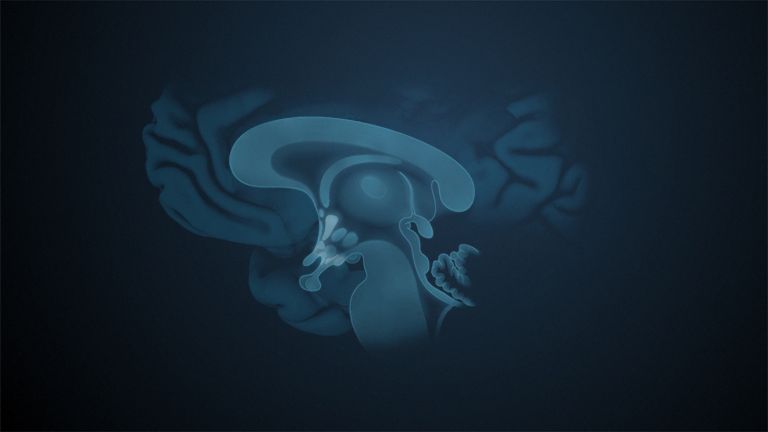

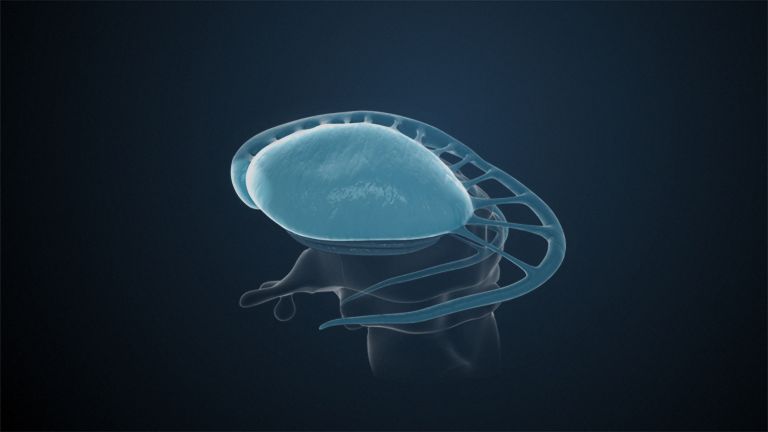

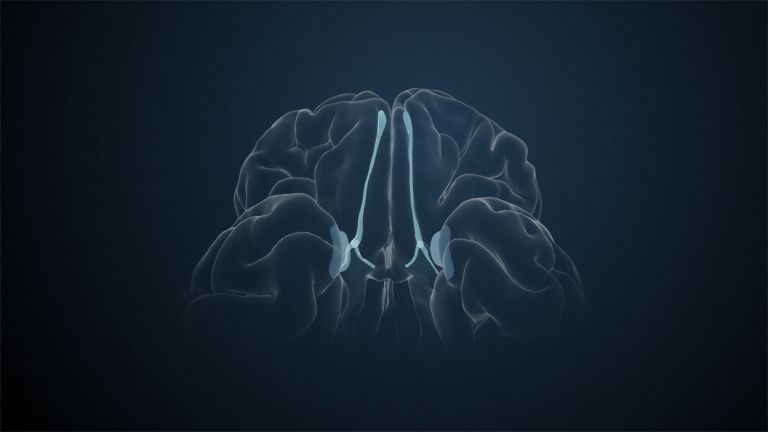

The Medulla oblongata and Pons together form the floor of the fourth ventricle, the rhombic fossa. The floor? Well, basically it is a wall – at least in bipedal animals that stand upright. Furthermore, the medulla and pons are so similar that some anatomists encourage their students to refer to the rhombencephalon instead. Although this also includes the cerebellum, the classification still makes sense when considering the development of the embryo – all three develop from the same vesicle of the neural tube.

Medulla oblongata

Area of the brain that transitions into the spinal cord. The medulla oblongata comprises nerve pathways between the spinal cord and higher brain regions, as well as numerous core areas with functions that are in some cases vital, such as breathing, heartbeat, and certain reflexes.

Pons

pons

Area in the brain stem between the medulla oblongata and the mesencephalon. It acts as a switching station for many nerve pathways between the brain and spinal cord and contains numerous nuclei, including cranial nerves and those involved in controlling motor function in cooperation with the cerebellum.

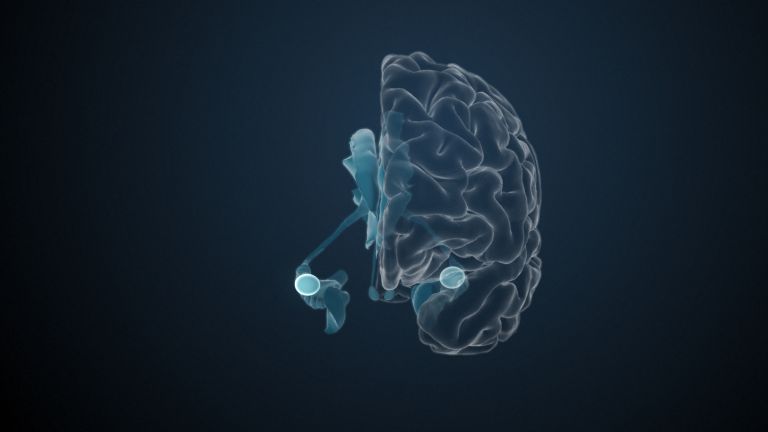

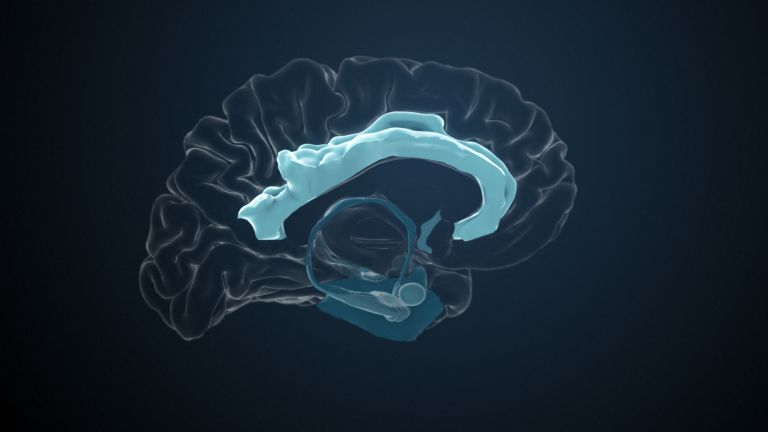

More than a bridge

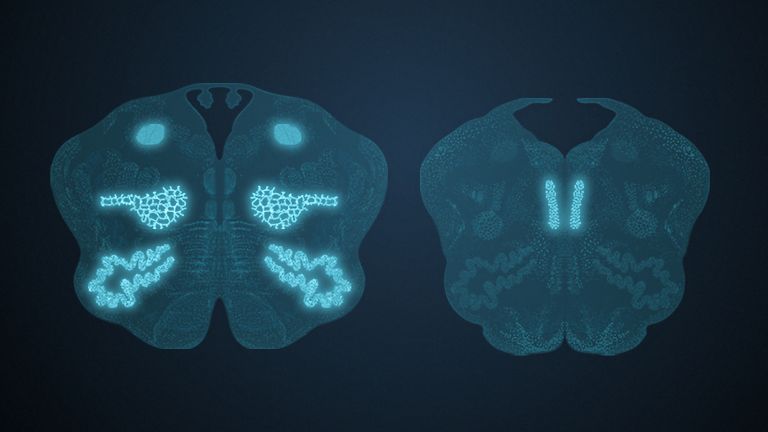

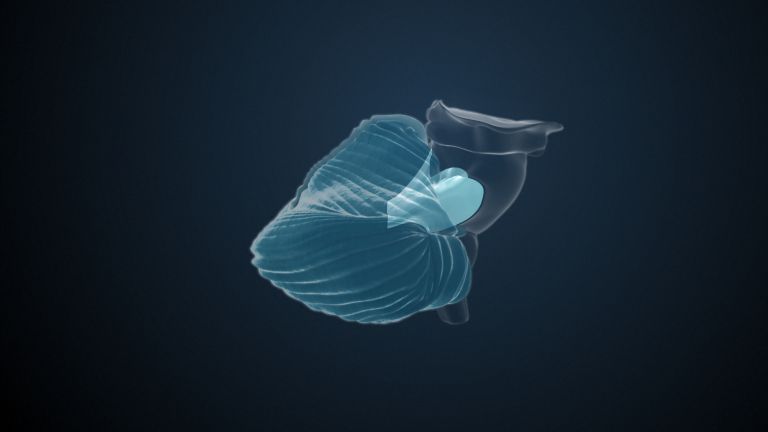

The conspicuous bulge consists mainly of a broad band of fibers. Earlier anatomists considered this to be a bridge connecting the two Cerebellar hemispheres directly – hence the name “bridge” (Pons Varolii), coined by the Italian anatomist Costanzo Varolio (1537–1575). However, this proved to be incorrect. Today we know that these are corticopontine fibers: pathways from the cerebral Cortex are switched in the pons and then continue as pontocerebellar pathways to the opposite cerebellar hemisphere.

But there is much more hidden in the pons. A fine groove, the sulcus basilaris, runs down the center of its front, through which the basilar artery, one of the large cerebral arteries, passes. The two elevations on the right and left give an idea of the course of the pyramidal tract inside. They connect the motor cortex with the spinal cord.

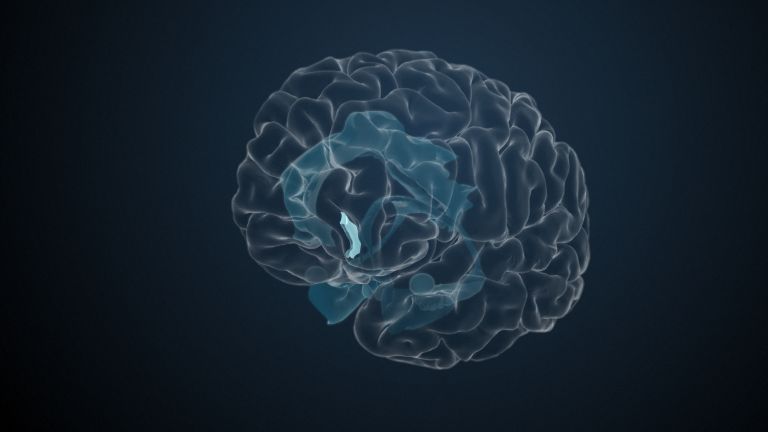

Surrounding these two elevations are numerous nuclei, the nuclei pontis. Their function can perhaps be compared to that of a bridge: by switching the corticopontine fibers mentioned above and sending them as pontocerebellar pathways to the opposite cerebellar hemisphere, they serve as a bridge for motor signals. Here, the voluntary motor signals from the cerebral cortex are forwarded as a kind of copy to the cerebellum, which then fine-tunes and refines the movement. In the front part of the pons, almost everything revolves around the fine-tuning of motor function.

Cerebellar hemispheres

Like the cerebrum, the cerebellum also has two hemispheres. The hemispheres are primarily responsible for finely tuned, purposeful movement control.

Pons

pons

Area in the brain stem between the medulla oblongata and the mesencephalon. It acts as a switching station for many nerve pathways between the brain and spinal cord and contains numerous nuclei, including cranial nerves and those involved in controlling motor function in cooperation with the cerebellum.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Recommended articles

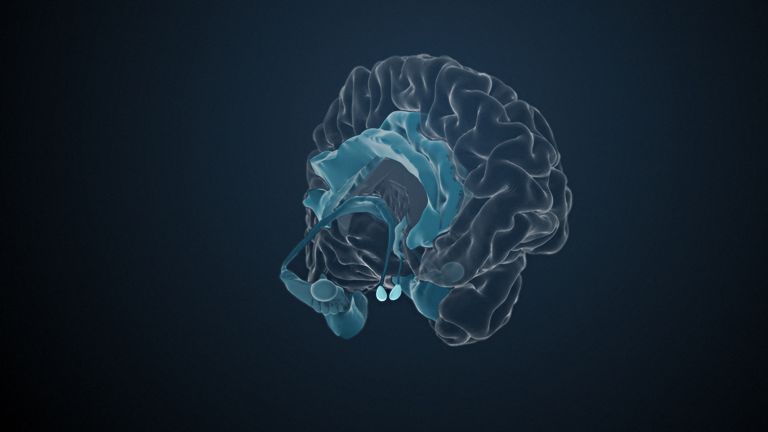

Vegetative tasks and consciousness

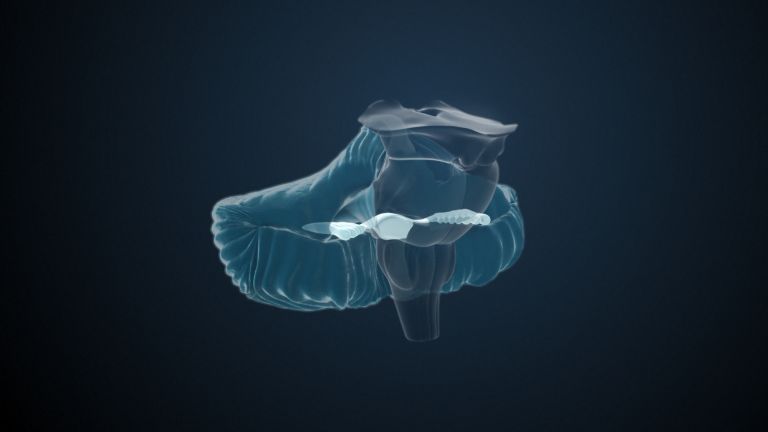

As mentioned above, the Pons is a continuation of the Medulla oblongata The two are closely linked in terms of function and are very similar in structure. The pons is where the Reticular formation network, which performs essential vegetative tasks, continues. While the medulla controls basic vegetative functions such as breathing rhythm, heartbeat, and blood pressure, the pons contains centers that fine-tune these processes. For example, it regulates the duration of inhalation and exhalation, and connects the control of breathing with other brain activities such as sleep or attention.

The ascending reticular activating system also runs through the pons. It transmits signals to the thalamus and from there to the cerebral cortex, ensuring that we remain awake and alert. Without the reticular activating system, consciousness is not possible. If it is severely damaged, consciousness can be lost.

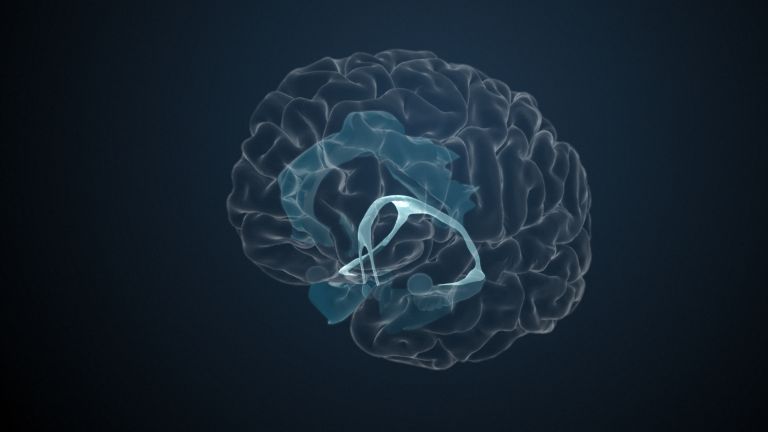

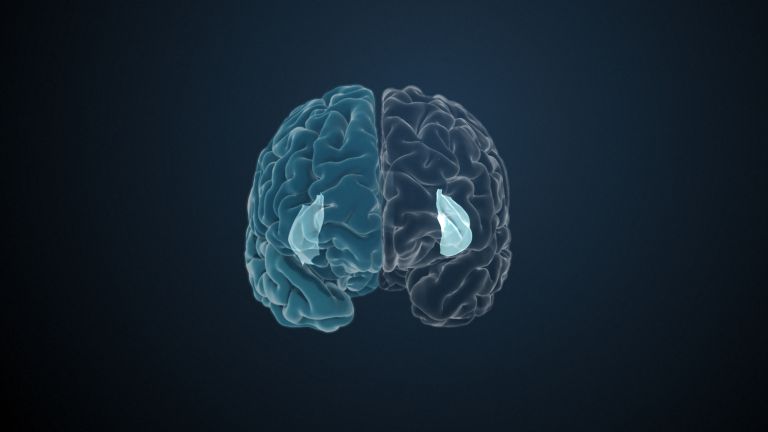

In addition to the countless nuclei of the pons, there are also several Cranial nerve nuclei. Only the fifth cranial nerve (Trigeminal nerve emerges directly from the pons. The third and fourth cranial nerves, on the other hand, leave above the pons fiber bundle, while the sixth, seventh, and eighth cranial nerves leave at the transition between the pons and the medulla oblongata.

The importance of these nuclei is also evident in clinical practice: in unconscious patients, simple reflex tests provide information about the integrity of the pons. The masseter reflex in particular highlights the trigeminal nerve: when the chin is tapped lightly, the jaw muscle contracts briefly, demonstrating the function of this nerve.

In the corneal reflex, on the other hand, the trigeminal nerve works together with the facial nerve, the seventh cranial nerve: when the Cornea is touched, the Eye closes immediately as a reflex. If these reflexes fail, this may indicate damage to the pons.

Pons

pons

Area in the brain stem between the medulla oblongata and the mesencephalon. It acts as a switching station for many nerve pathways between the brain and spinal cord and contains numerous nuclei, including cranial nerves and those involved in controlling motor function in cooperation with the cerebellum.

Medulla oblongata

Area of the brain that transitions into the spinal cord. The medulla oblongata comprises nerve pathways between the spinal cord and higher brain regions, as well as numerous core areas with functions that are in some cases vital, such as breathing, heartbeat, and certain reflexes.

Reticular formation

formatio reticularis

The reticular formation is a network of numerous nuclei in the brain stem. It has a variety of tasks, for example, it is responsible for alertness, the integration of motor, sensory, and vegetative processes, and the sleep-wake cycle.

attention

Attention

Attention serves as a tool for consciously perceiving internal and external stimuli. We achieve this by focusing our mental resources on a limited number of stimuli or pieces of information. While some stimuli automatically attract our attention, we can select others in a controlled manner. The brain also unconsciously processes stimuli that are not currently the focus of our attention.

cranial

A positional term – cranial means "towards the head." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction along the neural axis, i.e., forward.

In animals (without upright gait), the designation is simpler, as it always means forward. Due to the upright gait of humans, the brain bends in relation to the spinal cord, where cranial also means "upward."

Cranial nerve

A group of 12 pairs of nerves that originate directly in the brain, mostly in the brain stem. They are numbered with Roman numerals (I–XII). Unlike the rest, the first and second cranial nerves (olfactory and optic nerves) are not part of the peripheral nervous system, but rather the central nervous system.

Trigeminal nerve

Nervus trigeminus

In accordance with its literal translation, "triple nerve," the trigeminal nerve consists of three main branches: the ophthalmic branch, the maxillary branch, and the mandibular branch. The trigeminal nerve originates in the brain, where it is connected to four different nerve nuclei – three sensory and one motor. It reaches large parts of the head via the three branches. The sensory and motor fibers supply the face, nasal and oral cavities, and masticatory muscles.

Cornea

The cornea is the transparent front part of the outer layer of the eye. It is involved in refracting light, ensuring that the image of a distant object falls on the point of sharpest vision on the retina.

Eye

bulbus oculi

The eye is the sensory organ responsible for perceiving light stimuli – electromagnetic radiation within a specific frequency range. The light visible to humans lies in the range between 380 and 780 nanometers.

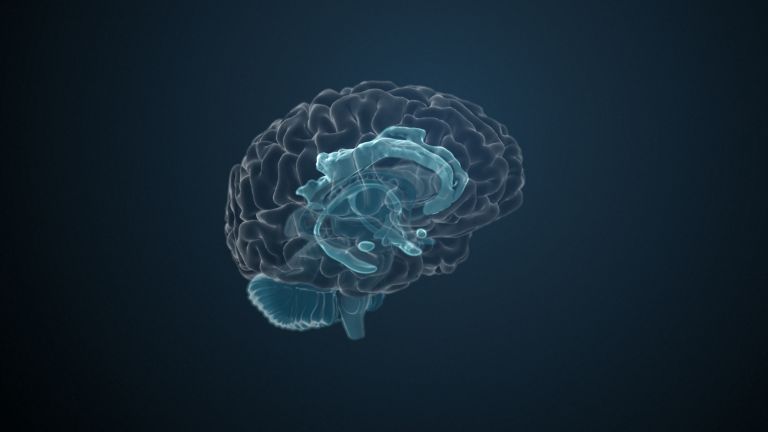

Taste, hearing, and other essential functions

Important sensory systems also converge in the Pons. Here, auditory signals are processed and forwarded to higher centers. Taste impressions reach the pons via special nuclei. Large pathways for touch, pain, and temperature also pass through this section of the brain stem.

Damage in this area is often serious because both vital functions and sensory perceptions can be affected. However, unusual symptoms sometimes occur. Normally, during REM sleep, the muscles are blocked by inhibitory pathways in the pons. If this Inhibition fails, for example in the case of a Lesion of the reticular formation, those affected actually act out their dreams: they lash out, kick, or shout in their sleep – a disorder that can only be controlled with medication.

Even more serious is extensive damage to the anterior pons region. This is where the pyramidal tracts run, which transmit movement commands from the Cerebrum to the Spinal cord If they are destroyed on both sides, for example due to an infarction of the basilar artery, the so-called locked-in syndrome occurs: Those affected are awake and conscious, can perceive their environment, but are almost completely paralyzed and can often only communicate through Eye movements.

Pons

pons

Area in the brain stem between the medulla oblongata and the mesencephalon. It acts as a switching station for many nerve pathways between the brain and spinal cord and contains numerous nuclei, including cranial nerves and those involved in controlling motor function in cooperation with the cerebellum.

Taste

The sensory impression we refer to as "taste" results from the interaction between our senses of smell and taste. In terms of sensory physiology, however, "taste" is limited to the impression conveyed to us by the taste receptors on the tongue and in the surrounding mucous membranes. It is currently assumed that there are five different types of taste receptors that specialize in the taste qualities sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami. In 2005, scientists also identified possible taste receptors for fat, whose role as a distinct taste quality is still being investigated.

Inhibition

Neuronal inhibition describes the phenomenon whereby a sender neuron sends an impulse to a receiver neuron, causing the latter's activity to decrease. The most important inhibitory neurotransmitter is GABA.

Lesion

A lesion is damage to organic tissue.

Cerebrum

telencephalon

The cerebrum comprises the cerebral cortex (gray matter), the nerve fibers (white matter), and the basal ganglia. It is the largest part of the brain. The cortex can be divided into four cortical areas: the temporal lobe, frontal lobe, occipital lobe, and parietal lobe.

Its functions include the coordination of perception, motivation, learning, and thinking.

Spinal cord

medulla spinalis

The spinal cord is the part of the central nervous system located in the spine. It contains both the white matter of the nerve fibers and the gray matter of the cell nuclei. Simple reflexes such as the knee-jerk reflex are already processed here, as sensory and motor neurons are directly connected. The spinal cord is divided into the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral spinal cord.

Eye

bulbus oculi

The eye is the sensory organ responsible for perceiving light stimuli – electromagnetic radiation within a specific frequency range. The light visible to humans lies in the range between 380 and 780 nanometers.

First published on August 28, 2011

Last updated on September 20, 2025