The Corpus Callosum

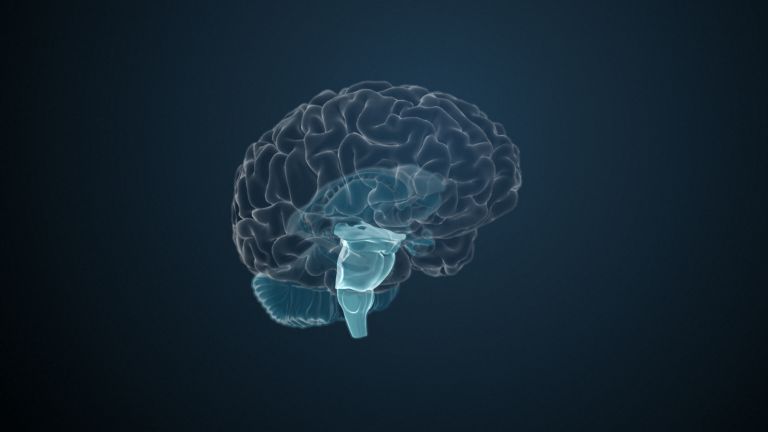

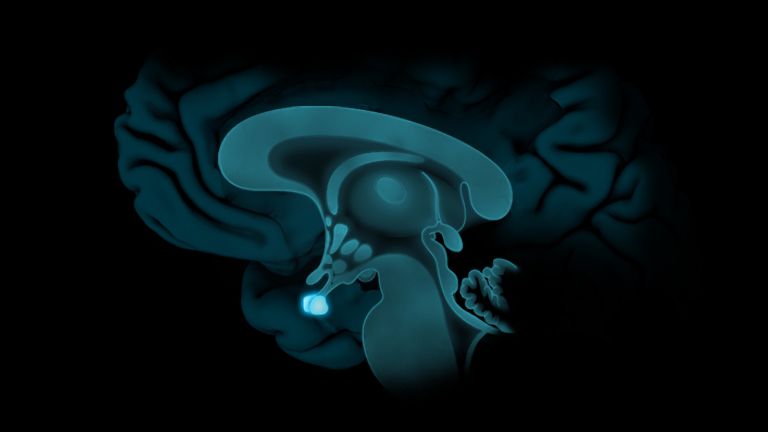

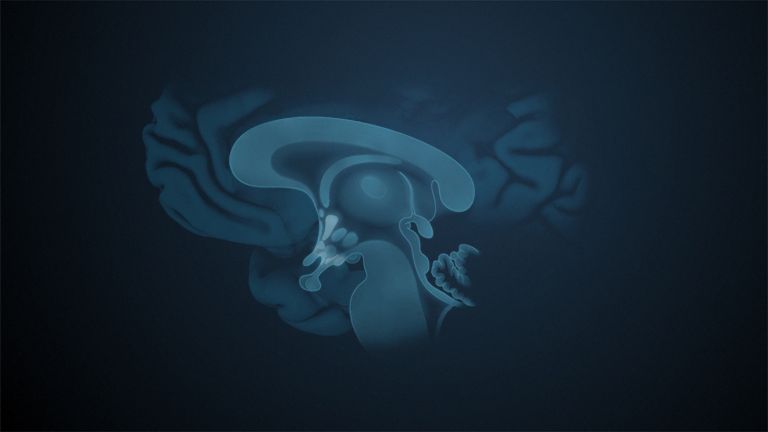

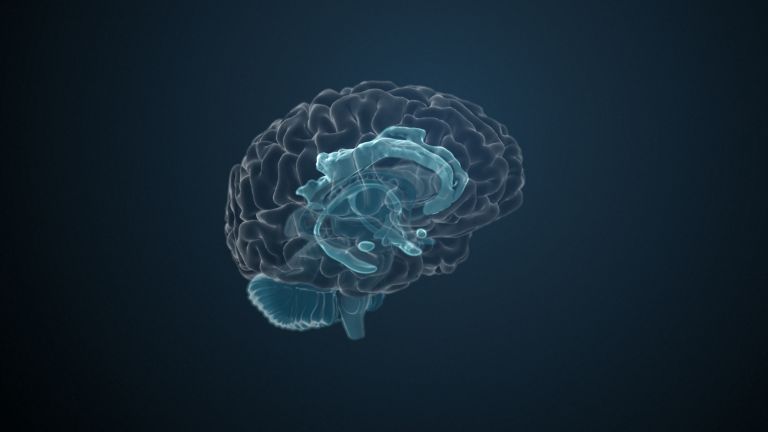

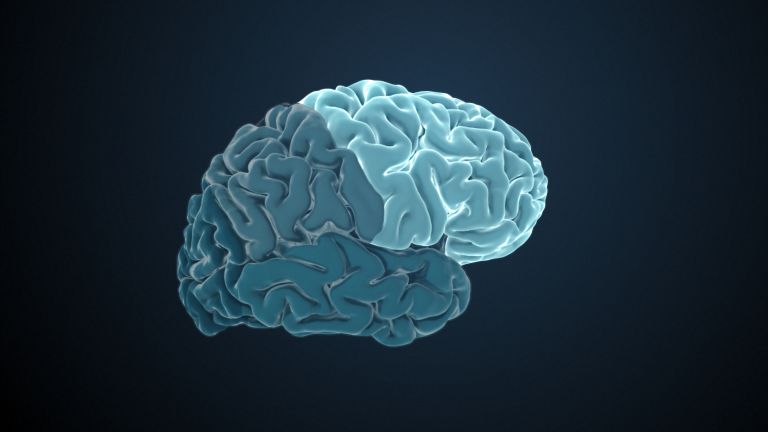

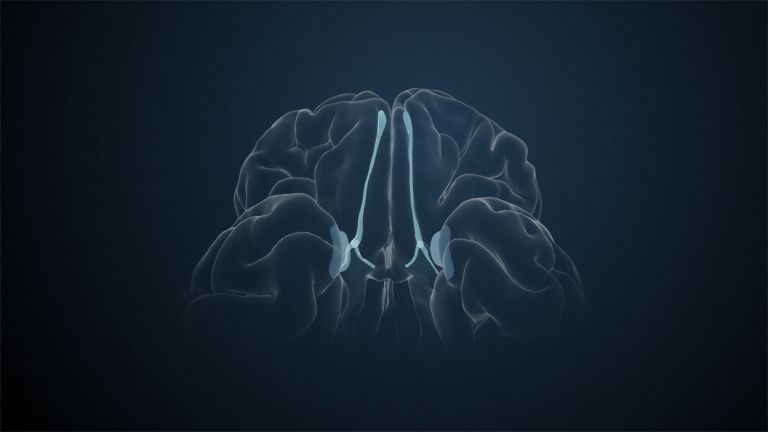

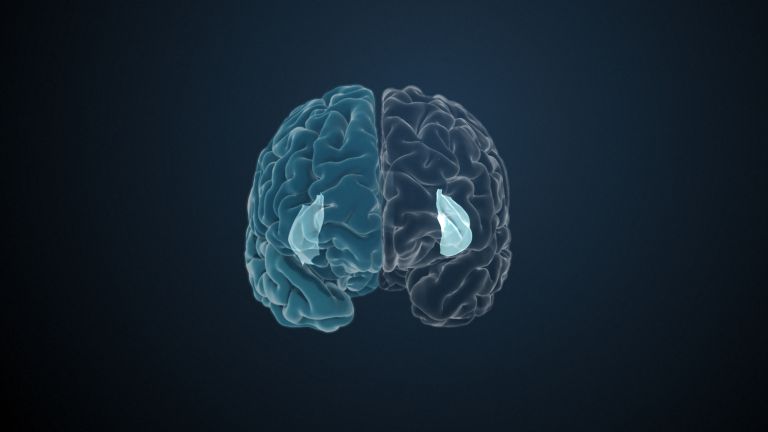

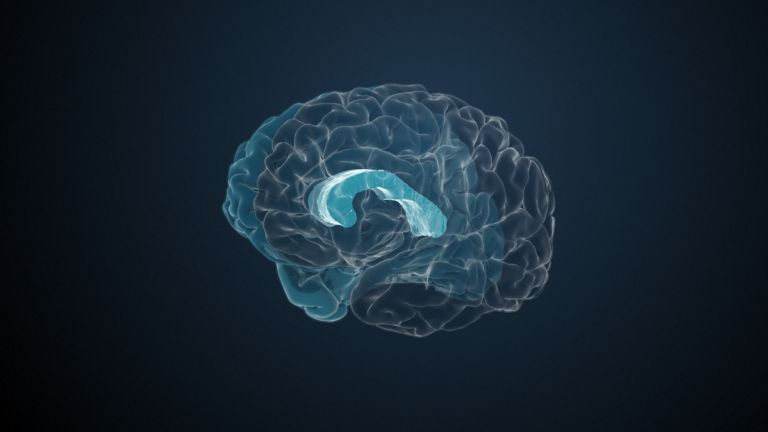

The brain has two halves – the observer can see this at first glance, as the edge of the mantle, the longitudinal fissure, divides the cerebrum into two hemispheres. This separating gap is bridged by the corpus callosum, a powerful structure consisting of around 200 million fibers in humans.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Oliver von Bohlen und Halbach

Published: 01.07.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

The corpus callosum is the most important pathway system for connecting the two hemispheres. It carries around 200 million fibers that enable the exchange of information. As the example of split-brain patients shows, this exchange of information is very important.

Within the brain, nearly everything revolves around the networking of neurons: Ascending and descending information must be transmitted from one nerve cell to the next, even if they are located in completely different brain regions. The brain can be considered a "small world" from the perspective of its connectivity, where each neuron is linked to any other neuron through only a few intermediaries. Within this networking, three functional types of fibers can be distinguished within the cortex:

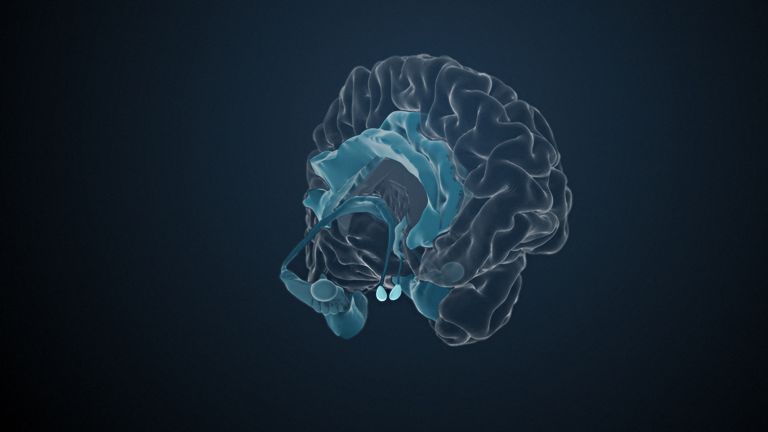

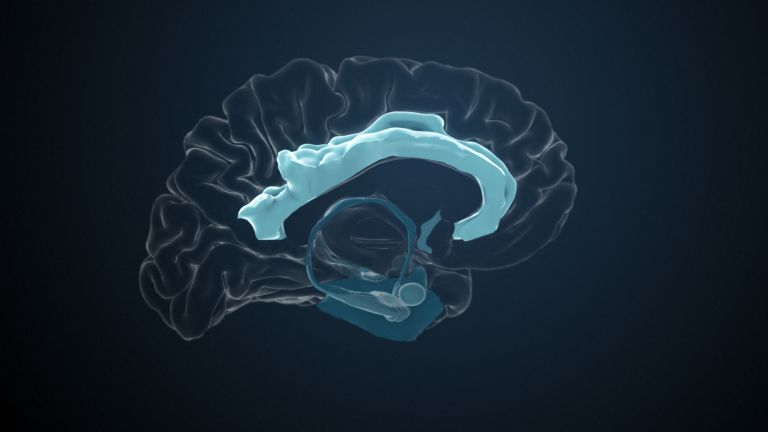

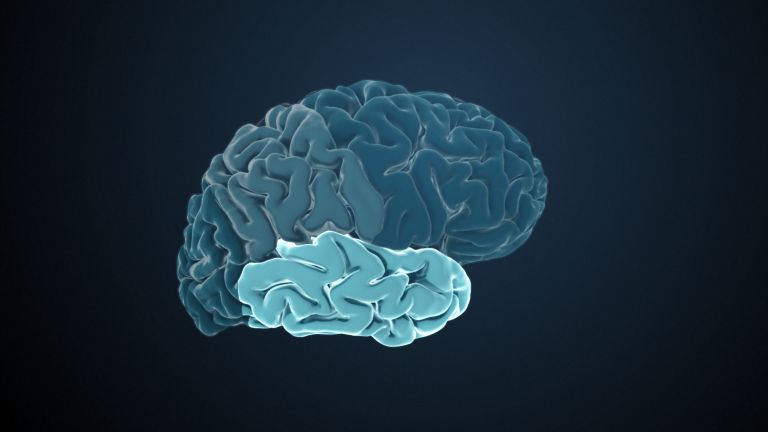

- Commissural fibers: These are represented by the corpus callosum, which connects the two hemispheres. In addition to the corpus callosum, other commissures include the anterior commissure, posterior commissure, and fornix.

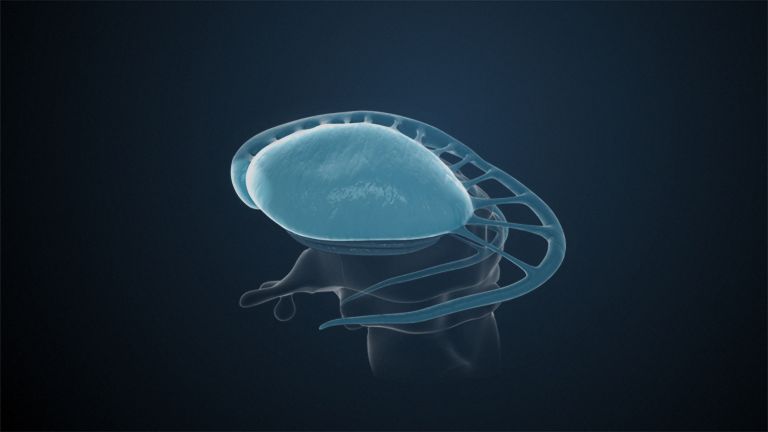

- Projection fibers: These fibers connect the cortex to subcortical regions, such as the thalamus or brainstem. One of the most prominent fiber tracts is the internal capsule (capsula interna).

- Association fibers: These fibers link individual cortical areas within one hemisphere, such as the prefrontal cortex with the motor cortices.

A connecting structure is urgently needed, as the two cerebral hemispheres not only perform partially distinct functions but also process, in most cases, information from the opposite side of the body. In the primary visual cortex, for instance, information from the left visual field is processed by the right hemisphere. Nevertheless, we do not experience an overlap of slightly different perspectives from each visual field – we perceive a single, coherent image of the environment. This clearly illustrates the importance of information exchange between both hemispheres.

Fanning out

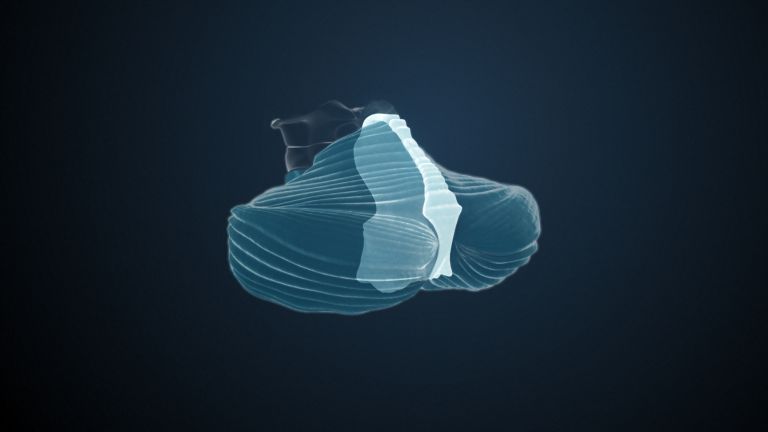

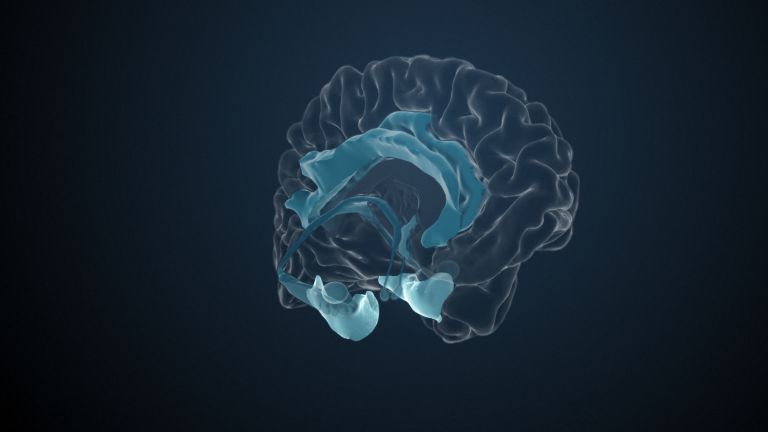

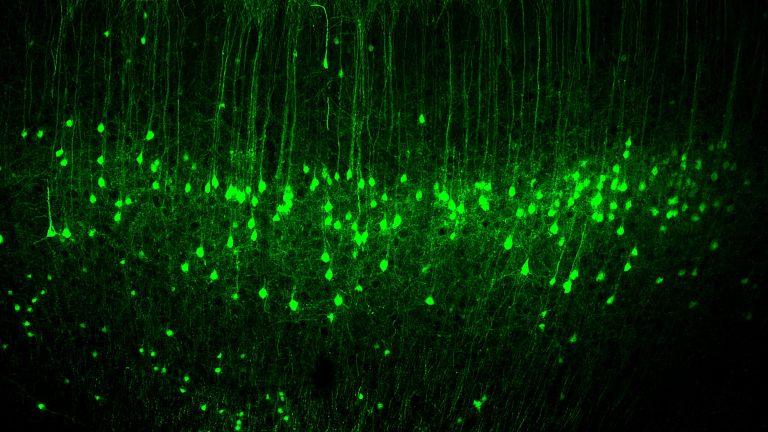

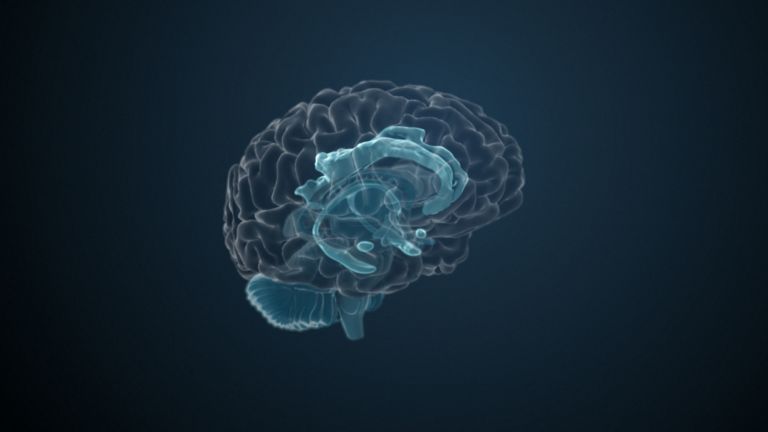

The corpus callosum is the critical structure for this information exchange – throughout its entire length, so-called commissural fibers cross from one hemisphere to the other. These fibers are composed of the axons of pyramidal cells from one cortical area and connect it to the corresponding area of the opposite hemisphere.

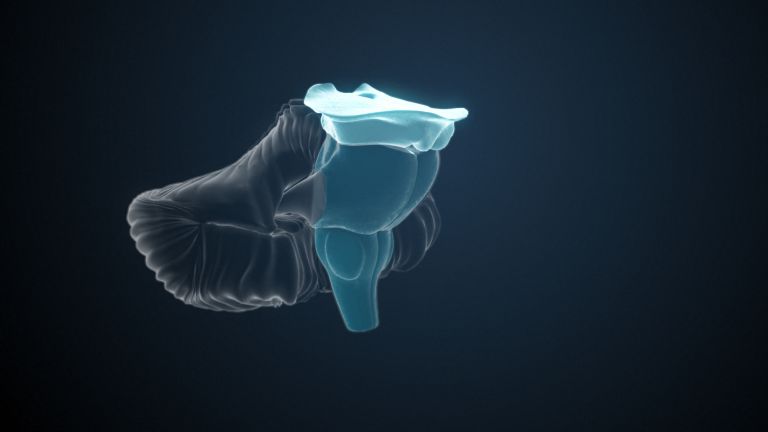

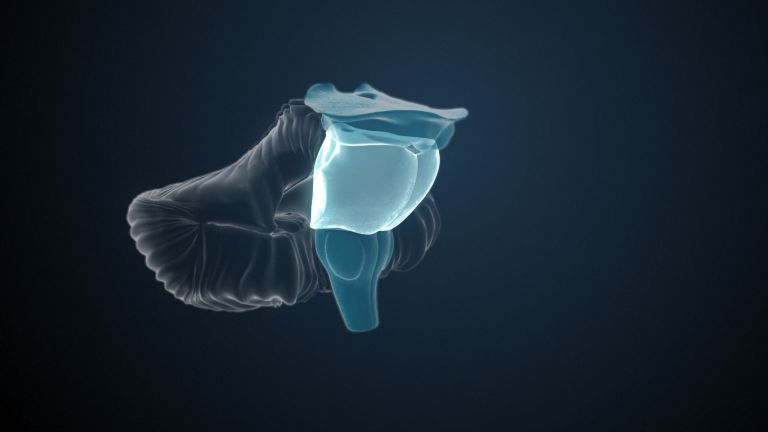

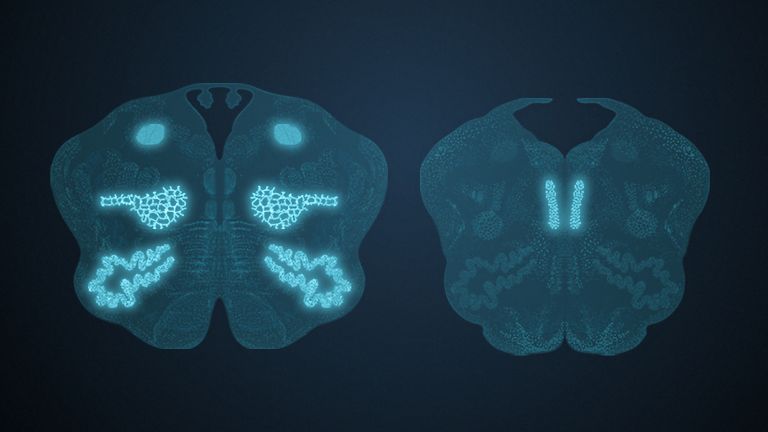

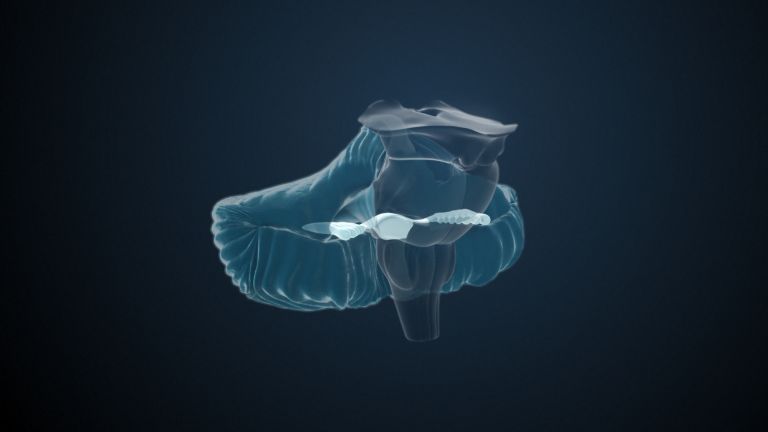

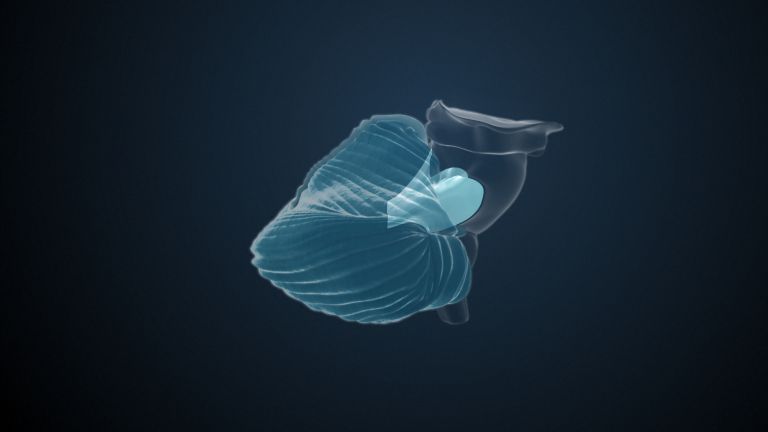

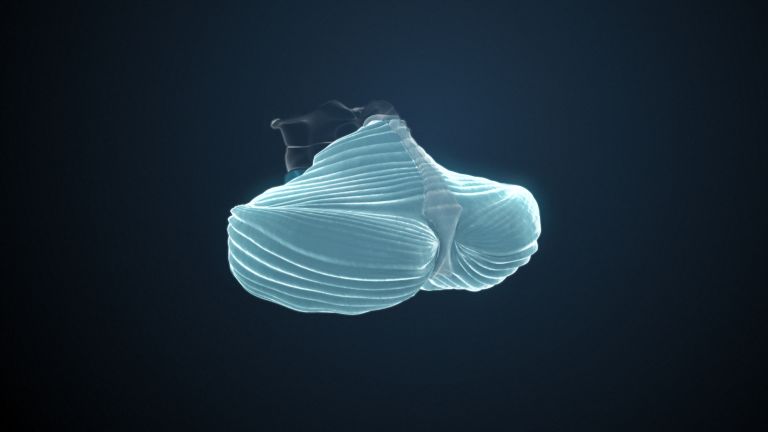

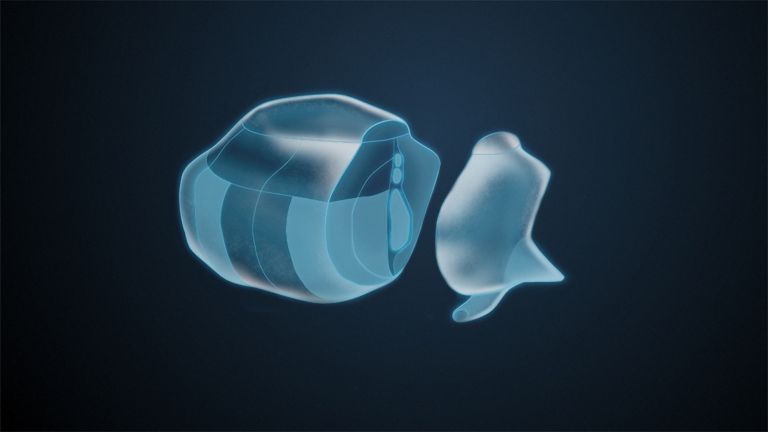

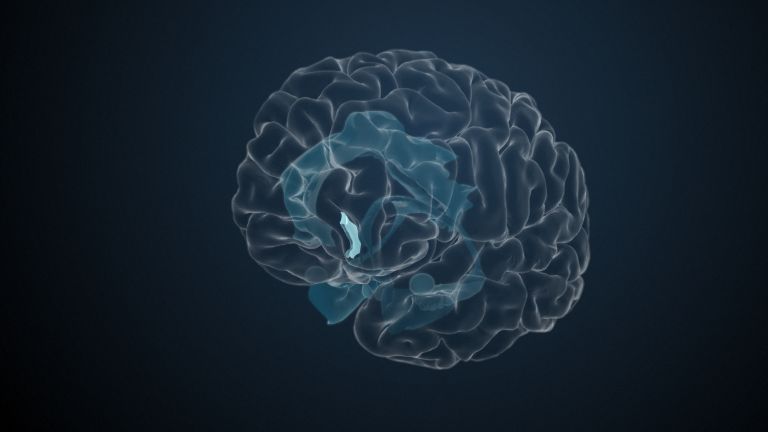

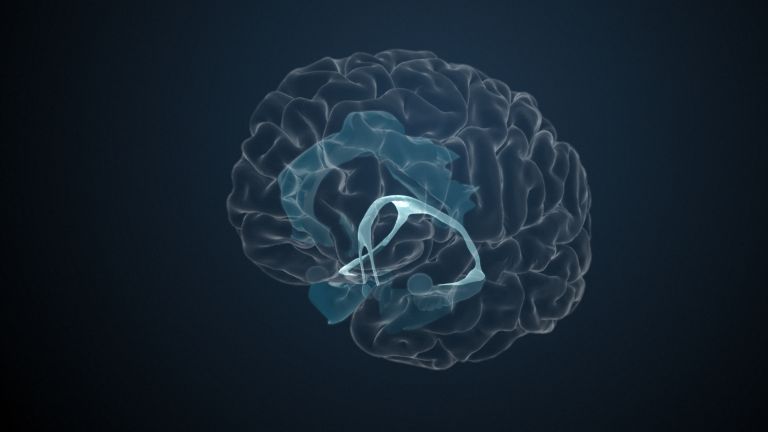

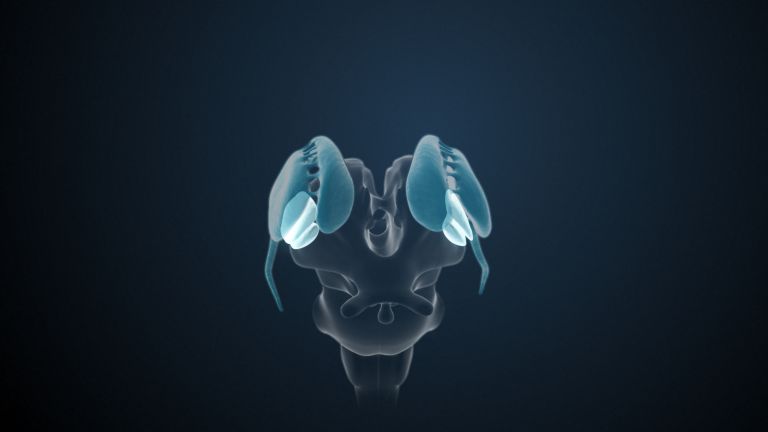

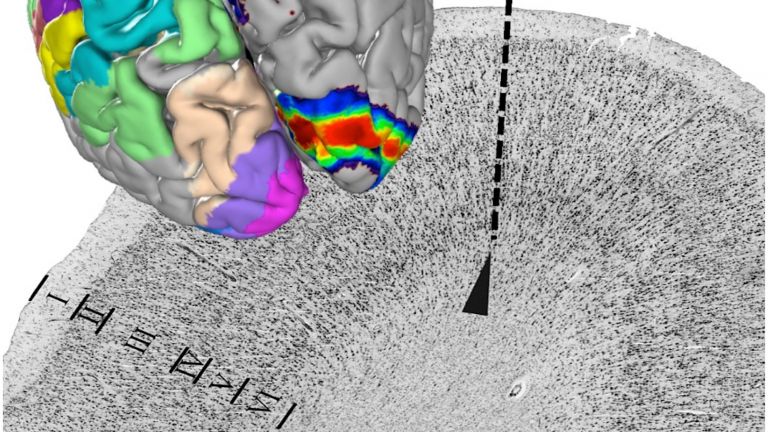

The curved structure of the corpus callosum is particularly well visible in a longitudinal section along the central sulcus. Individual sections can then be distinguished, which anatomists refer to as the rostrum, genu, truncus, and splenium. When dissected from above, the corpus callosum appears as a beautiful fan-shaped fiber system. Its fibers run transversely in the central region, bend in a frontal direction in the anterior part, and curve in an occipital direction in the posterior part. Within the corpus callosum, fibers connecting the two frontal lobes are termed the forceps frontalis, while those linking the two occipital lobes are referred to as the forceps occipitalis.

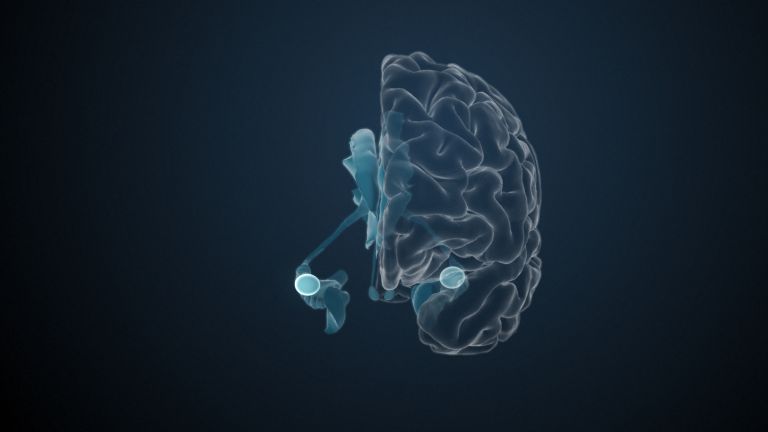

All this sounds very dry and anatomical, and hardly does justice to the corpus callosum. Its true beauty has only been revealed since we have been able to examine it using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and process the data accordingly. Jeff Lichtman was one of the first researchers to succeed in creating such a “work of art.” At the same time, these images also give us an initial idea of how ambitious the goal of connectome research is: the aim is to identify the connections between each neuron and every other neuron – and this goes far beyond the corpus callosum.

Recommended articles

Failures

As already mentioned, the commissural fibers serve to transmit impulses from one hemisphere of the brain to the other. In the case of severe epileptic seizures, this is not desirable, as the seizure can jump from one hemisphere to the other via the corpus callosum. For this reason, the corpus callosum has been surgically severed in particularly severe cases of epilepsy (so-called “callosotomy”). Surprisingly, this drastic intervention resulted in no noticeable impairments in the daily lives of so-called “split-brain” patients. Among medical professionals, this has even led to humorous speculation that the primary function of the corpus callosum might simply be holding the two hemispheres together.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Roger Sperry, along with Michael Gazzaniga and Joseph LeDoux, conducted detailed studies on split-brain patients. Images were presented to these patients, but only to either the left or right visual field, and thus only to one hemisphere – the opposite hemisphere, because processing always takes place contralaterally.

This yielded surprising findings: the test subjects were able to correctly describe an image that was presented in the right visual field and therefore processed in the left hemisphere. However, if the image was only presented in the left visual field – and thus processed on the right – the test subjects reacted as if they had not seen the image. And they were certainly unable to name its content. However, they were able to correctly identify the object shown, such as a screw or a pair of scissors, by touching it with their left hand.

This small mystery is solved relatively quickly: in most right-handed people, the language centers are located in the left hemisphere. When the right visual field “informed” it about the image, it was able to respond accordingly. The right hemisphere does not have access to language production, but it can always move the left arm and process its tactile information. In normal everyday life, this separation is eliminated because both hemispheres receive visual impressions.

The bigger mystery, however, is part of the big question “Who am I?” Because it is quite obvious that under these experimental conditions, one half of the brain of split-brain patients does not know what the other half knows. And it acts autonomously, so to speak. Further research showed impressive results in terms of consciousness and cognitive organization, and Roger Sperry received the Nobel Prize for his research in 1981.

In addition to this well-known disconnection syndrome, the corpus callosum seems to play a role in other diseases as well. For instance, it is reduced in size in cases of schizophrenia and altered in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

Published on September 22, 2011

Last updated on July 1, 2025