The Cerebellum

The cerebellum is located at the back of the skull and has a precise structure. But its uniform structure is deceptive: it precisely coordinates movements and additionally appears to be involved in a variety of sensory, emotional, and cognitive abilities.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Jochen F. Staiger

Published: 05.08.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

Tightrope walkers, pianists, and baseball players demonstrate the capabilities of the Cerebellum. But even reaching for a full cup of coffee is complex: Where is the cup? Where is the hand that is supposed to grasp it? The cerebellum integrates a wealth of relevant information, coordinates the activity of numerous muscles, and checks the sequence of movements. It is still unclear exactly how it works and to what extent it is involved in many other tasks. What is clear, however, is that its name and small size are deceptive: the cerebellum is in no way inferior to the Cerebrum in terms of the complexity of its tasks and the number of its neurons.

Cerebellum

Cerebellum

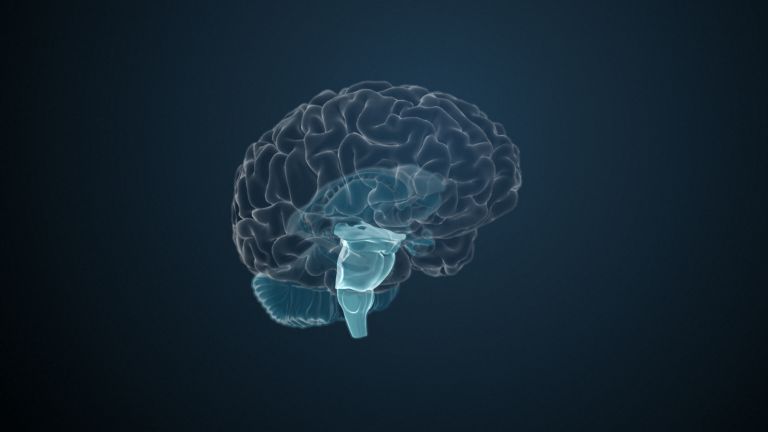

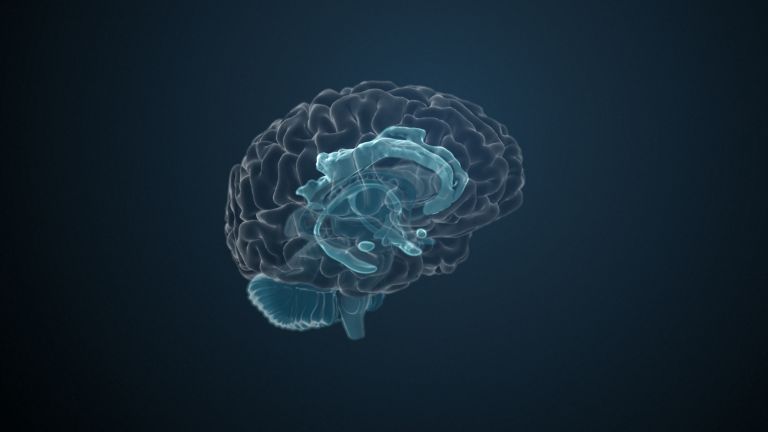

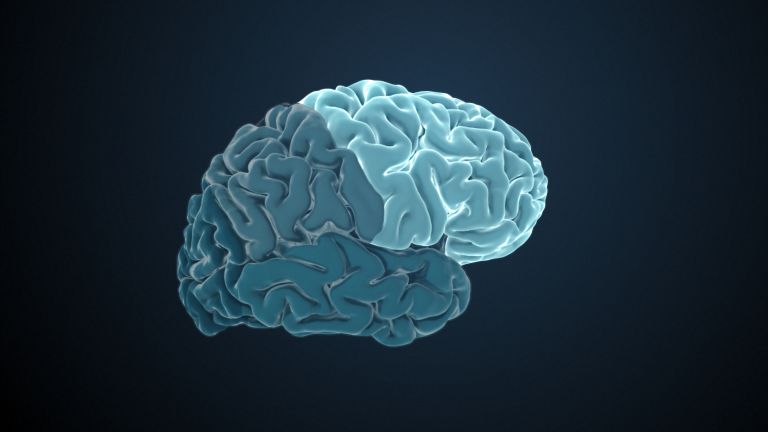

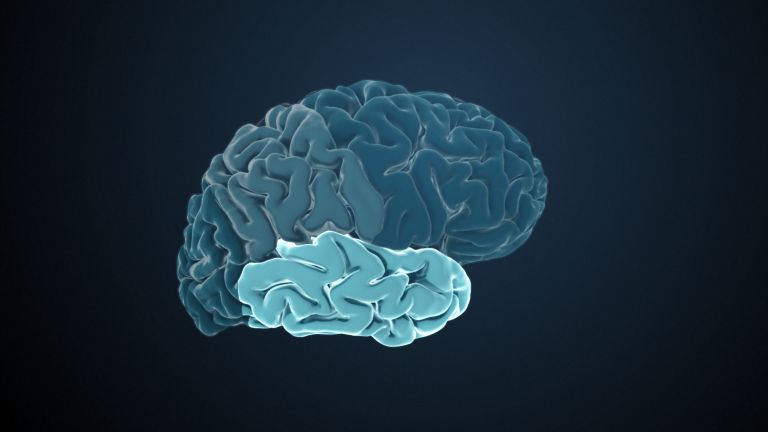

The cerebellum is an important part of the brain, located at the back of the brain stem and below the occipital lobe. It consists of two cerebellar hemispheres covered by the cerebellar cortex and plays an important role in motor processes, among other things. It develops from the rhombencephalon.

inferior

An anatomical position designation – inferior means located further down, the lower part.

Cerebrum

telencephalon

The cerebrum comprises the cerebral cortex (gray matter), the nerve fibers (white matter), and the basal ganglia. It is the largest part of the brain. The cortex can be divided into four cortical areas: the temporal lobe, frontal lobe, occipital lobe, and parietal lobe.

Its functions include the coordination of perception, motivation, learning, and thinking.

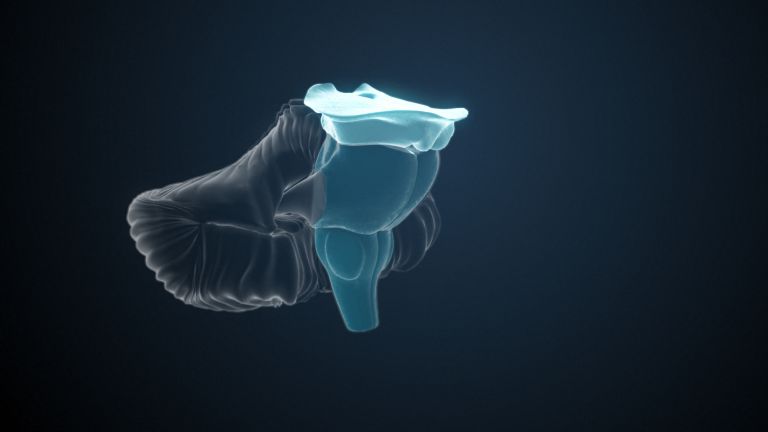

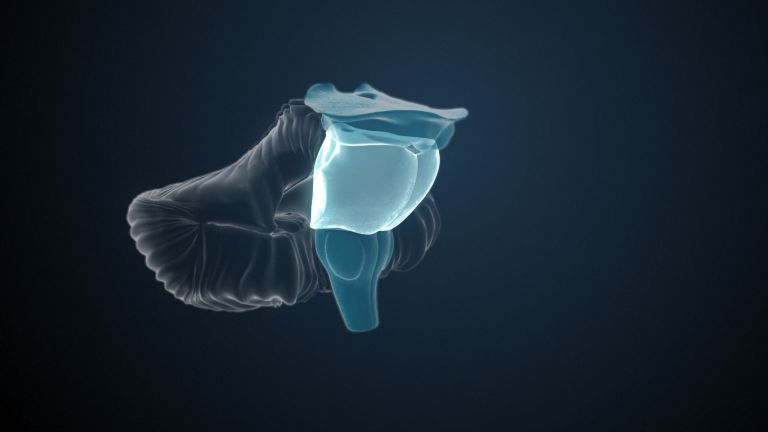

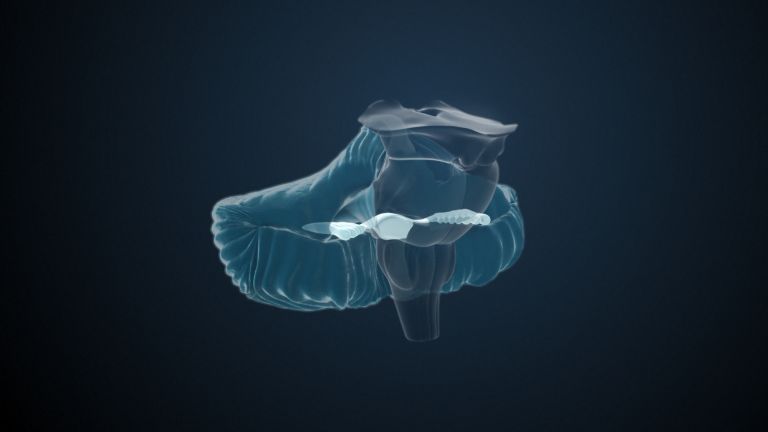

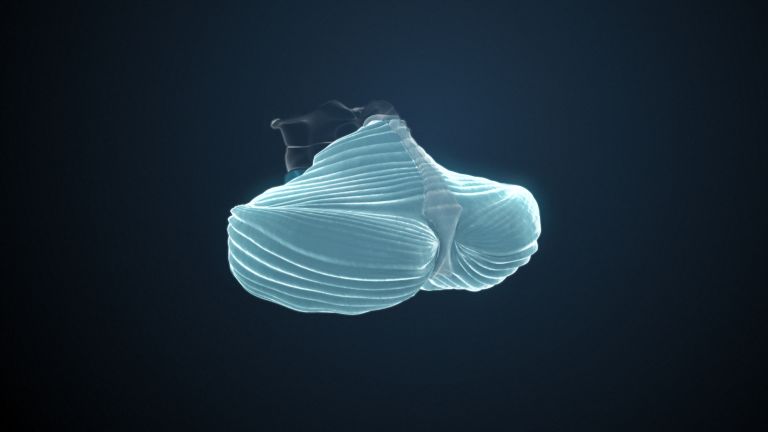

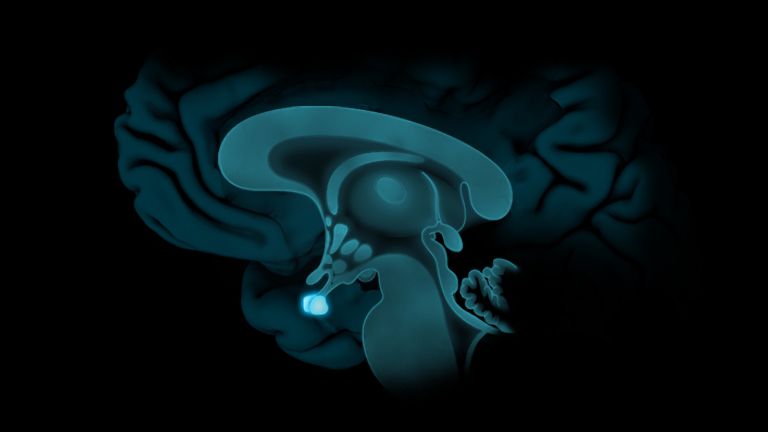

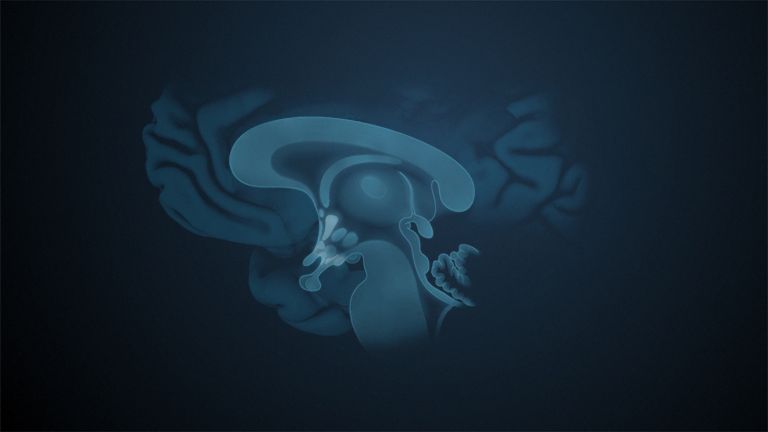

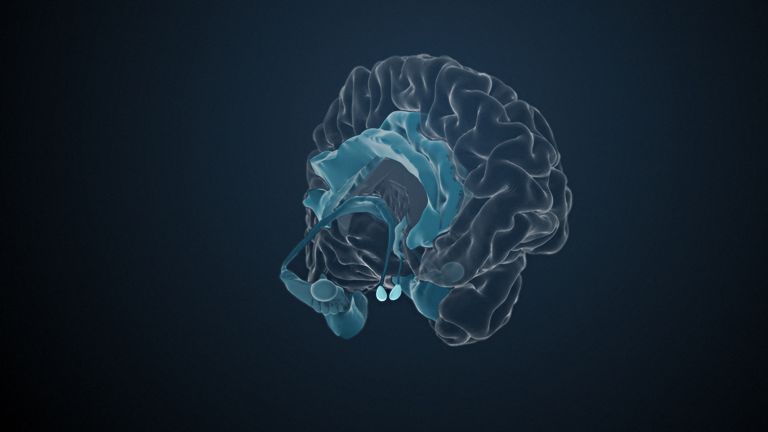

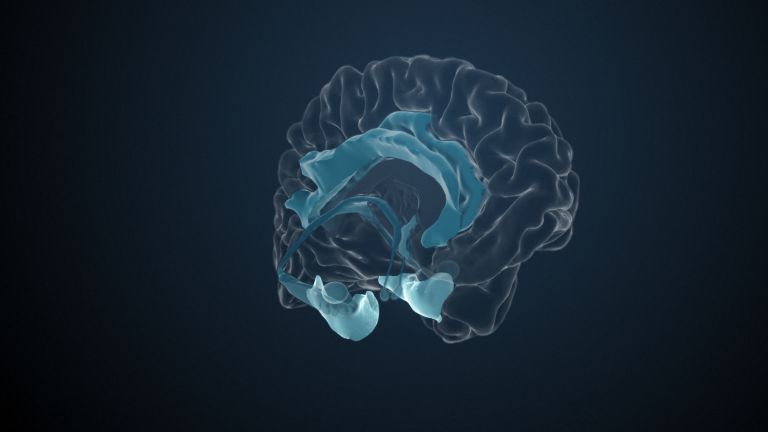

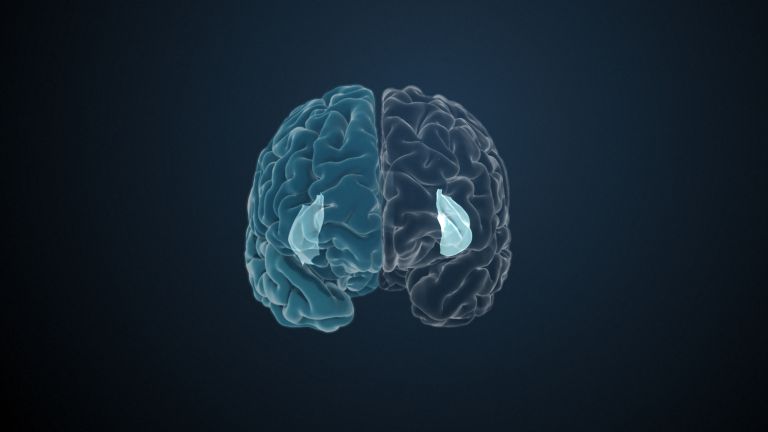

The Cerebellum is located at the back of the skull, below the Cerebrum and behind the Brain stem Its two halves are clearly visible from the outside and, like the halves of the cerebrum, are referred to as hemispheres. They are connected by the vermiform body, the cerebellar worm.

When English neurologist Gordon Holmes (1876−1965) examined soldiers with cerebellar injuries in 1917, he realized: “The cerebellum can be seen as an organ that supports movement.” In fact, imaging techniques now confirm that the cerebellum coordinates and modulates movements: whether you are reaching for a coffee cup, playing the piano, or doing a somersault – the neurons in the cerebellum are firing. But Holmes underestimated the cerebrum's little brother.

Cerebellum

Cerebellum

The cerebellum is an important part of the brain, located at the back of the brain stem and below the occipital lobe. It consists of two cerebellar hemispheres covered by the cerebellar cortex and plays an important role in motor processes, among other things. It develops from the rhombencephalon.

Cerebrum

telencephalon

The cerebrum comprises the cerebral cortex (gray matter), the nerve fibers (white matter), and the basal ganglia. It is the largest part of the brain. The cortex can be divided into four cortical areas: the temporal lobe, frontal lobe, occipital lobe, and parietal lobe.

Its functions include the coordination of perception, motivation, learning, and thinking.

Brain stem

truncus cerebri

The "trunk" of the brain, to which all other brain structures are "attached," so to speak. From bottom to top, it comprises the medulla oblongata, the pons, and the mesencephalon. It transitions into the spinal cord below. It is a center for vital functions such as breathing and heartbeat and contains ascending and descending pathways between the cerebrum, cerebellum, and spinal cord.

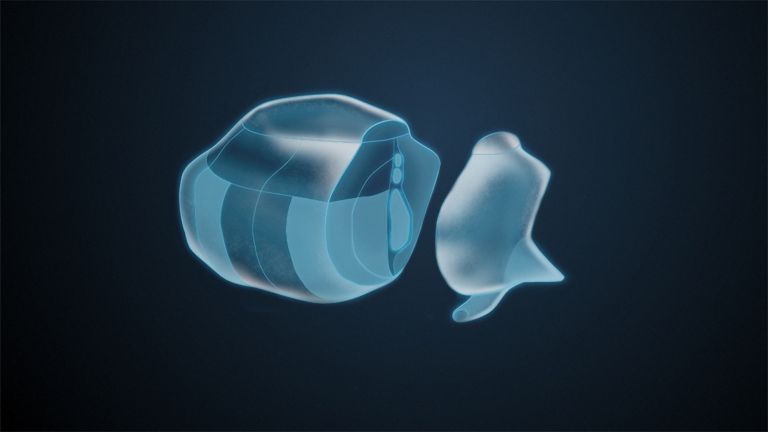

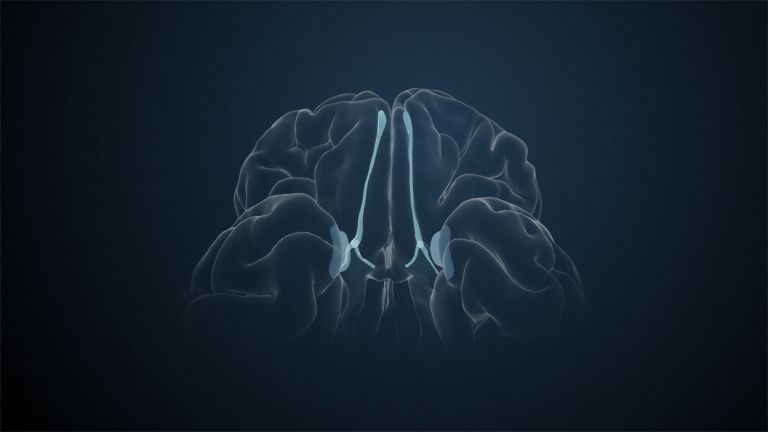

Structure

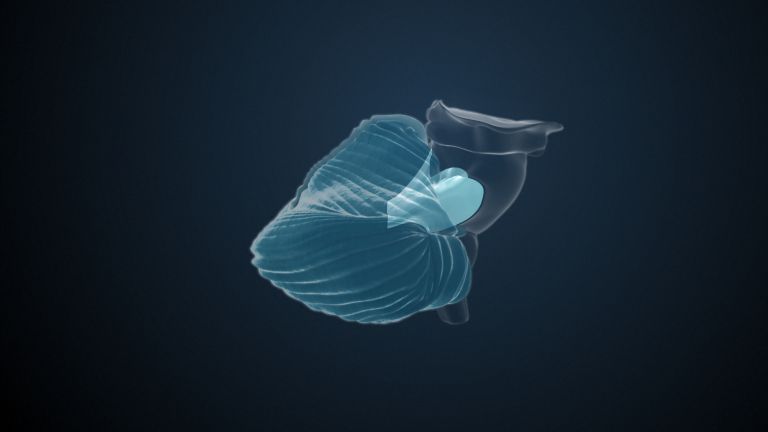

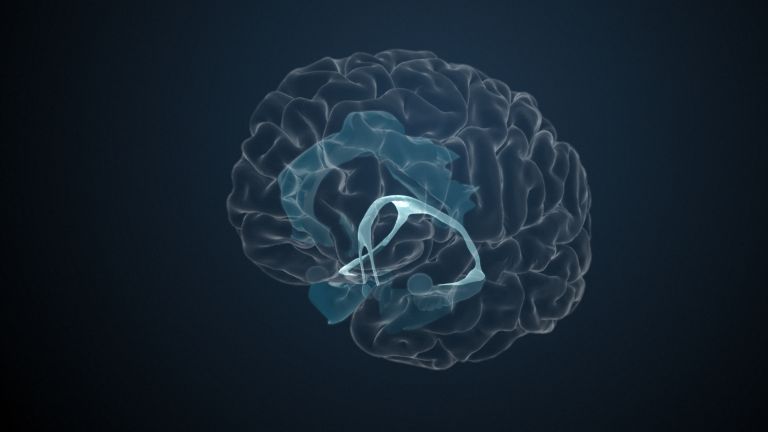

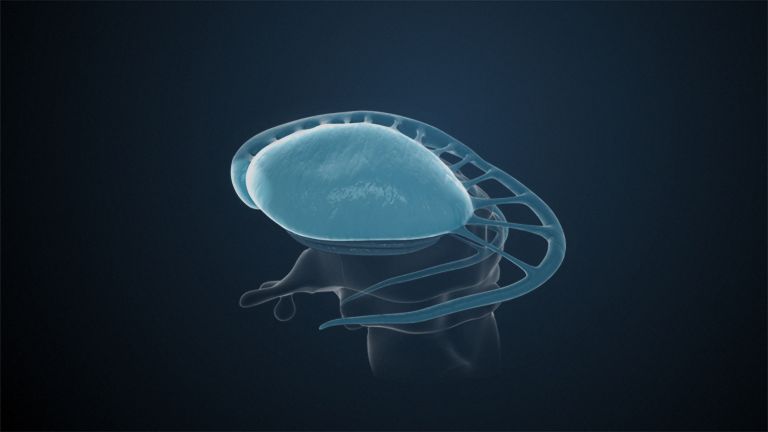

Although it is only about one-sixth the volume of the cerebrum, the Cerebellum has five times more neurons. In order to accommodate so much nerve mass in such a small space, the cerebellar cortex, the outer layer of the cerebellum, is heavily folded. The resulting folds are called folia. If you cut one of the Cerebellar hemispheres lengthwise, you can see the reason for this name: like the branches of a tree, the white matter of nerve fibers branches out inside. Anatomists refer to it as the “tree of life”: the “arbor vitae”. And the folds of the Cerebellar cortex seem to hang like leaves from its branches. The roots of the tree are formed by the cerebellar peduncles, which run from the cerebellum to the Brain stem The cerebellum receives and transmits information via these fibers.

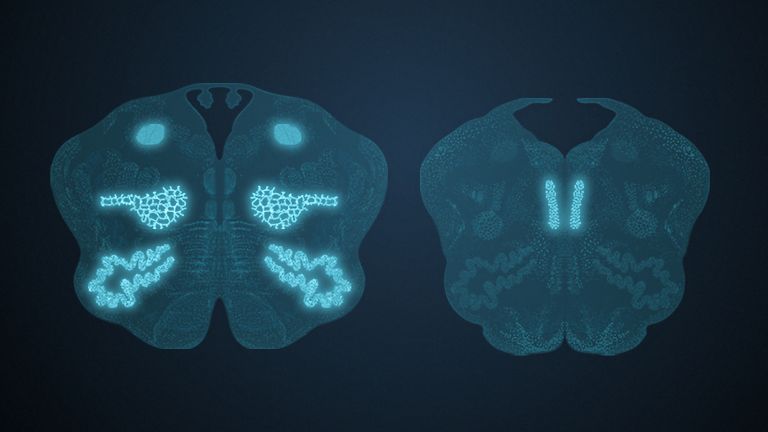

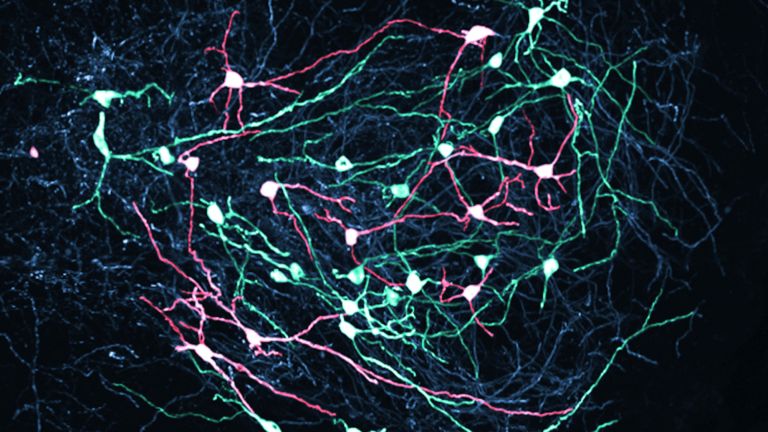

The tree of life is surrounded by the Gray matter of the nerve cells. And as can be seen at the microscopic level, this is also structured with extraordinary precision. The same three cell layers are found throughout the cerebellar Cortex: the molecular layer, the Purkinje cell layer, and the granular cell layer, viewed from the outside in. The middle layer is particularly striking – it contains the large Purkinje cells, neatly arranged next to each other like a layer of cherries in a cake. They are the central switching points of the cerebellar cortex: With their widely branched Dendrite trees, they receive excitatory and inhibitory information from almost all other cortical neurons. There can be up to 200,000 synapses on a single dendrite tree. The Purkinje cells transmit their inhibitory signals to the permanently active cerebellar nuclei, clusters of nerve cells deep in the white matter. From there, the impulses travel via the Cerebellar peduncles to other areas of the brain outside the cerebellum.

Cerebellum

Cerebellum

The cerebellum is an important part of the brain, located at the back of the brain stem and below the occipital lobe. It consists of two cerebellar hemispheres covered by the cerebellar cortex and plays an important role in motor processes, among other things. It develops from the rhombencephalon.

Cerebellar hemispheres

Like the cerebrum, the cerebellum also has two hemispheres. The hemispheres are primarily responsible for finely tuned, purposeful movement control.

white matter

The white matter refers to the myelinated fibers of the nervous system that connect one neuron to another. The white color is caused by the myelin sheath surrounding the fibers.

Cerebellar cortex

Cerebellar cortex

The cortex of the cerebellum, which, like that of the cerebrum, is composed of gray matter, or nerve cells. It consists of three layers and is highly folded, creating what are known as foliae, or leaves.

Brain stem

truncus cerebri

The "trunk" of the brain, to which all other brain structures are "attached," so to speak. From bottom to top, it comprises the medulla oblongata, the pons, and the mesencephalon. It transitions into the spinal cord below. It is a center for vital functions such as breathing and heartbeat and contains ascending and descending pathways between the cerebrum, cerebellum, and spinal cord.

Gray matter

Grey matter refers to a collection of nerve cell bodies, such as those found in nuclei or in the cortex.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Purkinje cell

Purkinje cells are the main output cells of the cerebellar cortex and central switching points of the cerebellum. They have a dense, tree-like dendritic apparatus through which they receive information from thousands of parallel fibers and climbing fibers. Their axons are the only ones that extend out of the cerebellar cortex and project onto the nuclei of the cerebellum, from where signals are transmitted to motor centers. Purkinje cells are among the largest cell types in the cerebellum.

Dendrite

Tree-like branching area of nerve cells whose extensions act as a kind of antenna for receiving electrical impulses from other cells.

excitatory

Exciting synapses are described as excitatory when they depolarize the subsequent cell membrane and can thus lead to the formation of an action potential. An excitatory effect is usually produced by an exciting transmitter (messenger substance), such as glutamate. The opposite is an inhibitory synapse.

Cerebellar peduncles

pedunculi cerebelli

Three fiber connections on the right and left sides that connect the cerebellum to the brain stem. All afferent and efferent fibers of the cerebellum run through these connections.

Recommended articles

Areas and connections

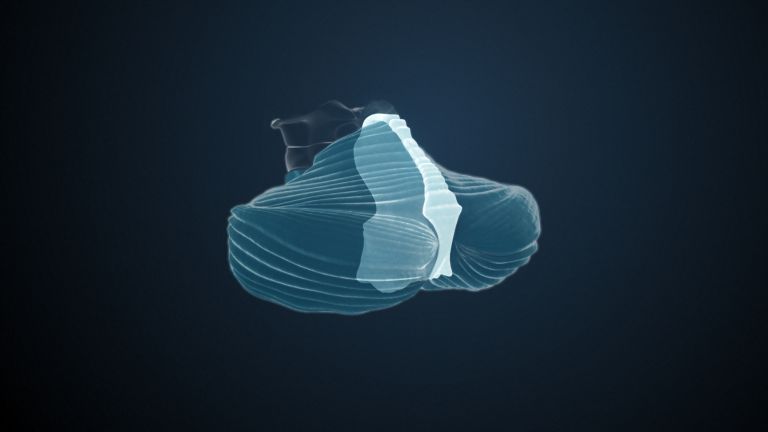

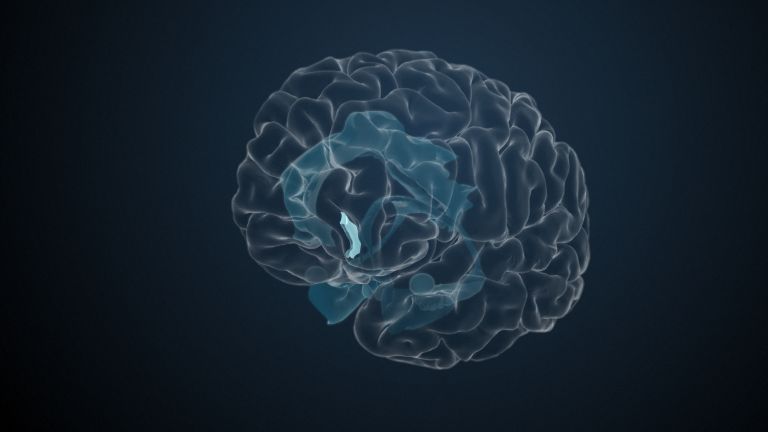

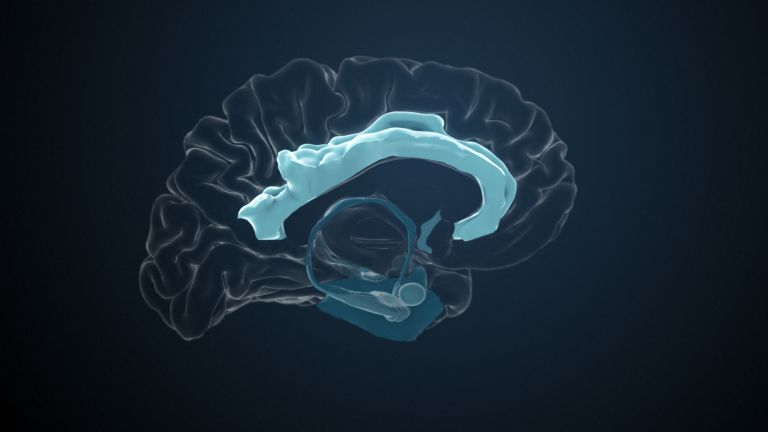

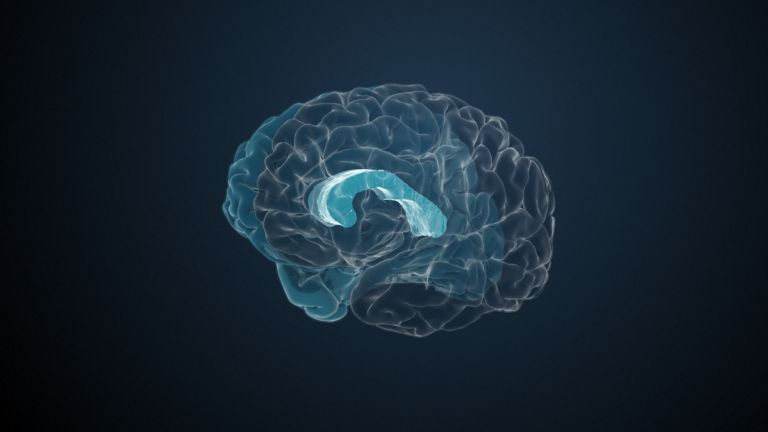

Anatomists divide the Cerebellum functionally into three areas that perform different tasks: the vestibulocerebellum, the spinocerebellum, and the pontocerebellum.

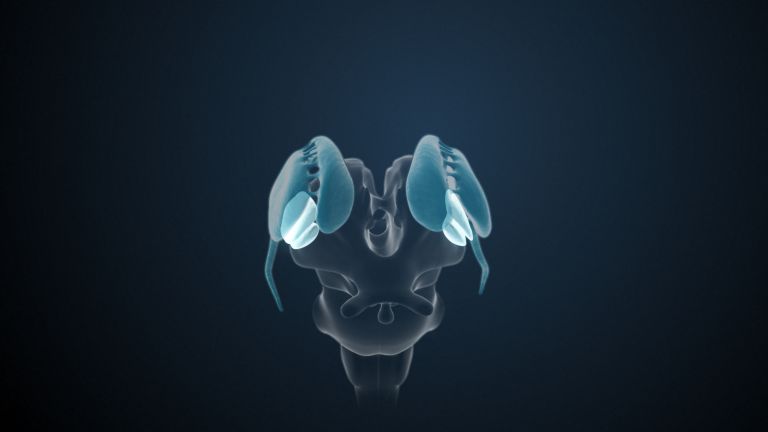

In terms of evolutionary history, the vestibulocerebellum is the oldest: it can even be found in living fossils such as fish-like, eel-shaped lampreys, although these have hardly changed in the last 500 million years. In humans, the vestibulocerebellum essentially consists of the anatomical structures nodulus and flocculus – collectively known as the Flocculonodular lobe – and, as the name suggests, it is functionally connected to the vestibular apparatus, i.e., the balance organ of the inner ear. We owe our ability to balance or walk upright to the vestibulocerebellum. It is also involved in controlling Eye movements.

The largest part of the cerebellar Vermis and a finger-width margin of the adjacent hemispheres together form the Spinocerebellum. It ensures that we can stand and walk without having to think about it. The spinocerebellum receives information from the Spinal cord about the position of the arms, legs, and trunk, as well as which muscles are tense and which are relaxed. It processes this information and sends it to the brain stem.

The pontocerebellum consists of almost the entire Cerebellar hemispheres It is closely connected to the Cerebrum via the pontine nuclei in the Brain stem Whenever we move something voluntarily, the pontocerebellum is involved: its tasks range from precise grasping to coordinating the laryngeal muscles when speaking. The pontocerebellum can be compared to a conductor. Instead of music, it studies movements, tunes them to its musicians – the muscles – and coordinates their interaction. The notes correspond to a movement plan provided by the cerebrum. If something goes wrong, the cerebellum intervenes, for example, if the floor is unexpectedly uneven or the coffee cup is empty and therefore lighter than expected. Cerebellar correction loops are extremely important for successfully completing disrupted movements – or learning them in the first place.

Although brain researchers have a rough idea of the tasks performed by the three areas of the cerebellum, they do not yet understand exactly how the vestibular, spinocerebellar, and pontocerebellar cerebellum perform all these motor tasks.

Cerebellum

Cerebellum

The cerebellum is an important part of the brain, located at the back of the brain stem and below the occipital lobe. It consists of two cerebellar hemispheres covered by the cerebellar cortex and plays an important role in motor processes, among other things. It develops from the rhombencephalon.

Flocculonodular lobe

lobus flocculonodularis

The flocculonodular lobe is an antero-inferior region of the cerebellum. It comprises two structures, the nodulus (nodule) and the flocculus (flocculus). It is involved in balance and spatial orientation, as well as in stabilizing and controlling eye movements. It corresponds to the vestibulocerebellum.

ear

auris

The ear is not only the organ of hearing, but also of balance. A distinction is made between the outer ear with the auricle and external auditory canal, the middle ear with the eardrum and ossicles, and the actual hearing and balance organ, the inner ear with the cochlea and semicircular canals.

Eye

bulbus oculi

The eye is the sensory organ responsible for perceiving light stimuli – electromagnetic radiation within a specific frequency range. The light visible to humans lies in the range between 380 and 780 nanometers.

Vermis

Cerebellar vermis

The vermis is an unpaired structure of the cerebellum located on the midline. It primarily receives somatosensory inputs.

Spinocerebellum

The area of the cerebellum that includes the cerebellar vermis and its adjacent areas. Involved in muscle tone and walking movements.

Spinal cord

medulla spinalis

The spinal cord is the part of the central nervous system located in the spine. It contains both the white matter of the nerve fibers and the gray matter of the cell nuclei. Simple reflexes such as the knee-jerk reflex are already processed here, as sensory and motor neurons are directly connected. The spinal cord is divided into the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral spinal cord.

Cerebellar hemispheres

Like the cerebrum, the cerebellum also has two hemispheres. The hemispheres are primarily responsible for finely tuned, purposeful movement control.

Cerebrum

telencephalon

The cerebrum comprises the cerebral cortex (gray matter), the nerve fibers (white matter), and the basal ganglia. It is the largest part of the brain. The cortex can be divided into four cortical areas: the temporal lobe, frontal lobe, occipital lobe, and parietal lobe.

Its functions include the coordination of perception, motivation, learning, and thinking.

Brain stem

truncus cerebri

The "trunk" of the brain, to which all other brain structures are "attached," so to speak. From bottom to top, it comprises the medulla oblongata, the pons, and the mesencephalon. It transitions into the spinal cord below. It is a center for vital functions such as breathing and heartbeat and contains ascending and descending pathways between the cerebrum, cerebellum, and spinal cord.

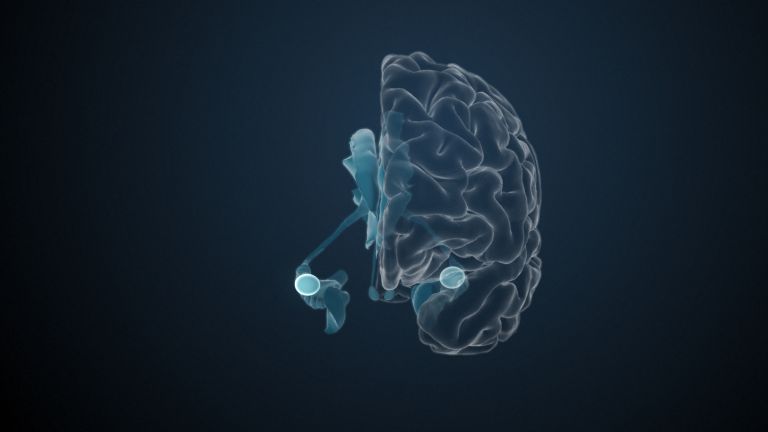

Tasks and failures

Recent studies suggest that the Cerebellum is not only responsible for motor skills. In 2005, neurologist Catherine Limperopoulos and her colleagues at McGill University in Montréal studied children who were born with cerebellar injuries. In addition to motor problems, the young patients also had difficulties with cognitive processes such as communication, social behavior, and visual Perception. Furthermore, imaging techniques show that activity in the cerebellum lights up during a variety of activities: for example, during Short-term memory tasks, the control of impulsive behavior, hearing and smelling, pain, hunger, shortness of breath, and much more. Neuroscientists do not yet know what role the cerebellum plays in these various tasks. A common hypothesis is that the cerebellum is responsible for the temporal coordination of the associated neural activity.

Despite the cognitive deficits mentioned above, motor problems are the main issue in cerebellar injuries. These largely correspond to what Holmes observed in his patients and what neurologists refer to as various types of “ataxia”: those affected have problems with balance and coordination; their gait is unsteady and similar to that of a heavily intoxicated person. When these patients reach for something, their hand trembles more as they get closer to the object. Their movements also often overshoot the target. Their speech sounds choppy. Their muscle tone is often reduced, making their bodies appear limp.

The patients' Eye movements are also noticeable. Their gaze moves jerkily, their eyes seem to tremble, and they often have to correct their eye position several times in order to fixate on an object.

Cerebellum

Cerebellum

The cerebellum is an important part of the brain, located at the back of the brain stem and below the occipital lobe. It consists of two cerebellar hemispheres covered by the cerebellar cortex and plays an important role in motor processes, among other things. It develops from the rhombencephalon.

Perception

The term describes the complex process of gathering and processing information from stimuli in the environment and from the internal states of a living being. The brain combines the information, which is perceived partly consciously and partly unconsciously, into a subjectively meaningful overall impression. If the data it receives from the sensory organs is insufficient for this, it supplements it with empirical values. This can lead to misinterpretations and explains why we succumb to optical illusions or fall for magic tricks.

Short-term memory

Short-term memory is a type of temporary storage in the brain where information can be retained for a few seconds to a few minutes. Its capacity is very limited, at 7±2 units of information (chunks). These can be numbers, letters, or words, for example. Today, this memory is usually considered within the framework of the working memory model, which also emphasizes the active processing of content.

Eye

bulbus oculi

The eye is the sensory organ responsible for perceiving light stimuli – electromagnetic radiation within a specific frequency range. The light visible to humans lies in the range between 380 and 780 nanometers.

First published on July 26, 2011

Last updated on August 5, 2025