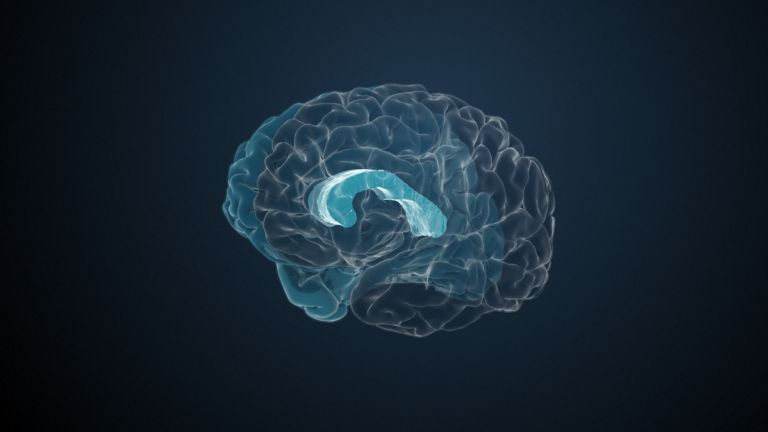

The Pallidum

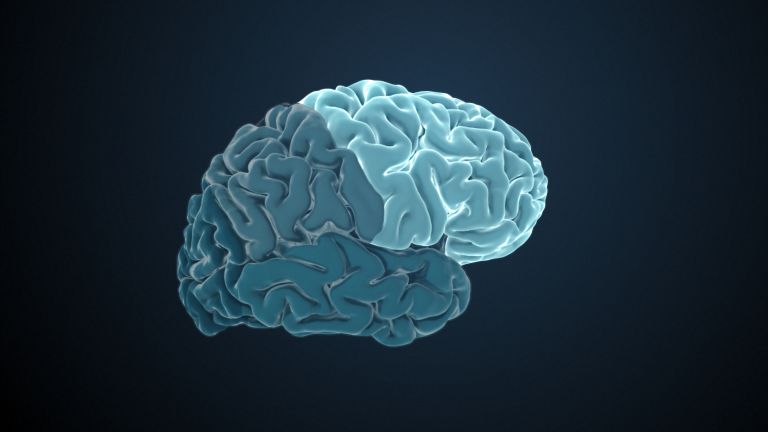

Movements are the result of a delicate balance between inhibition and excitation. The globus pallidus, the pale nucleus of the basal ganglia, does both, providing a prime example of highly complex feedback loops.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Horst-Werner Korf

Published: 23.11.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

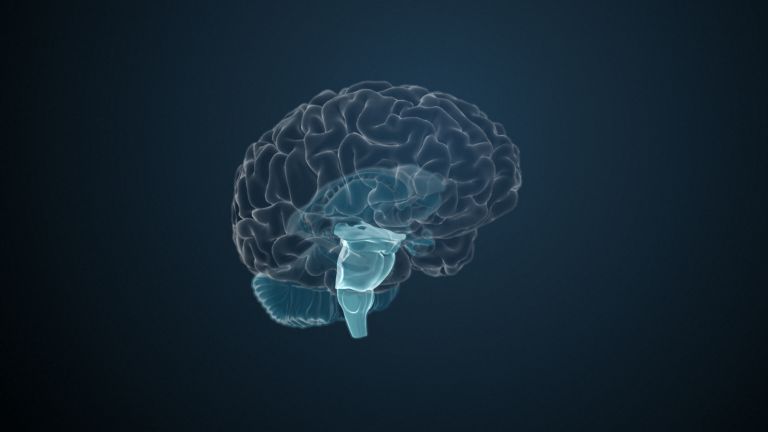

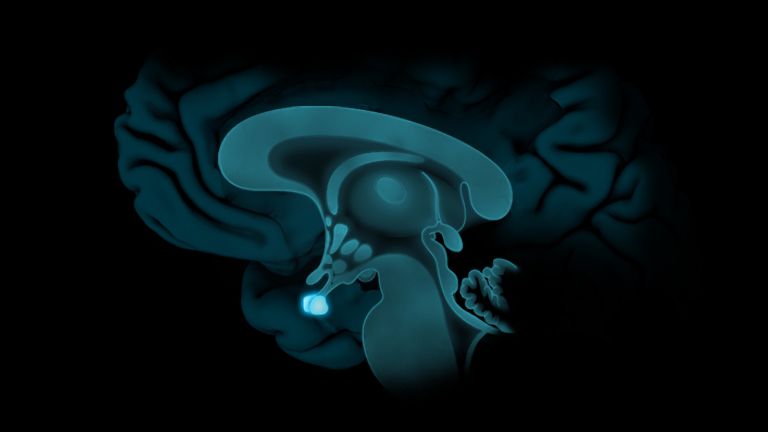

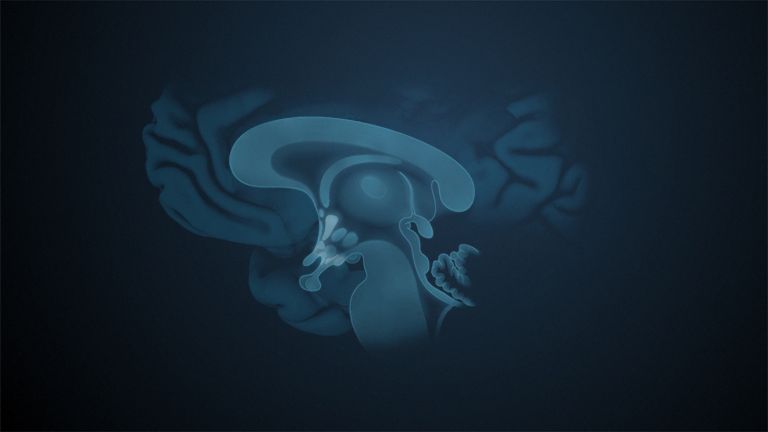

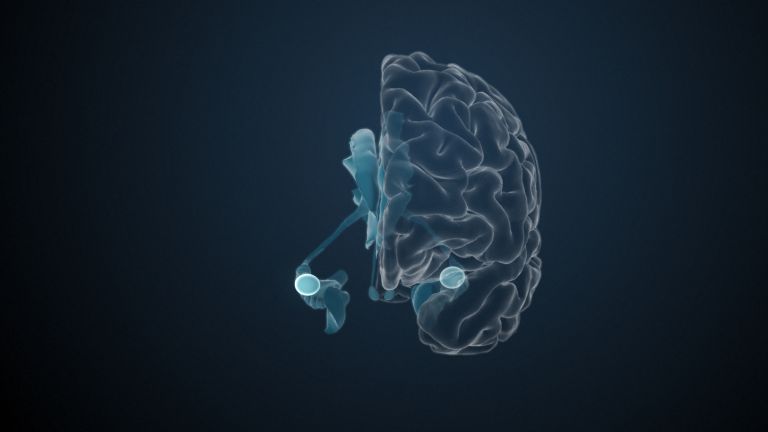

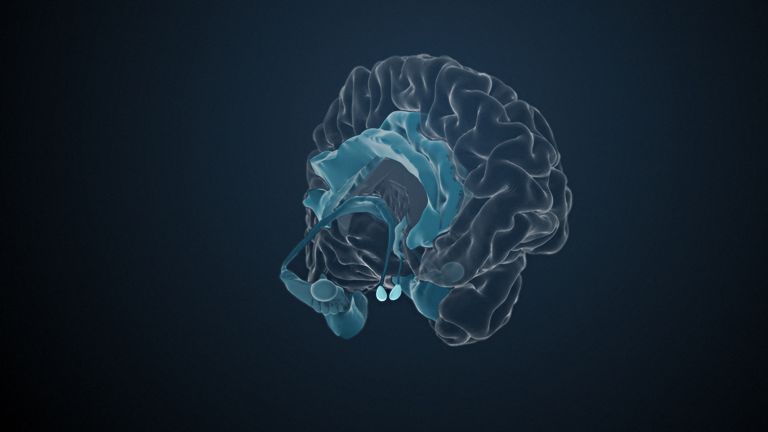

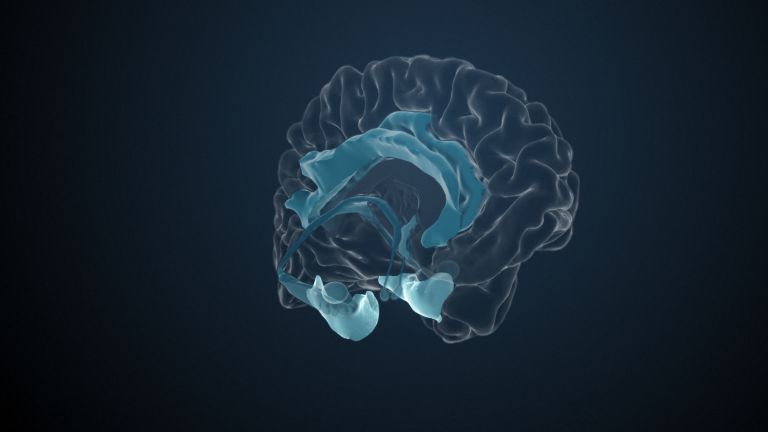

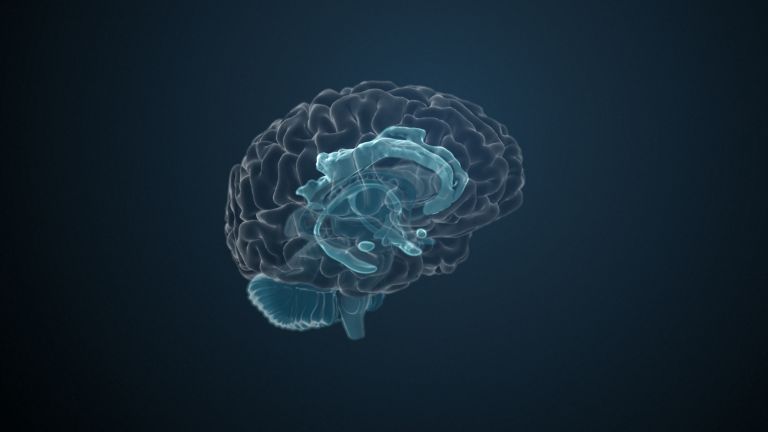

The pallidum is the output element of the basal ganglia. It modulates the motor activity of the cortex via the thalamus. Inhibitory and excitatory feedback loops between the cortex, striatum, globus pallidus, subthalamic nucleus, and thalamus play an important role in this process.

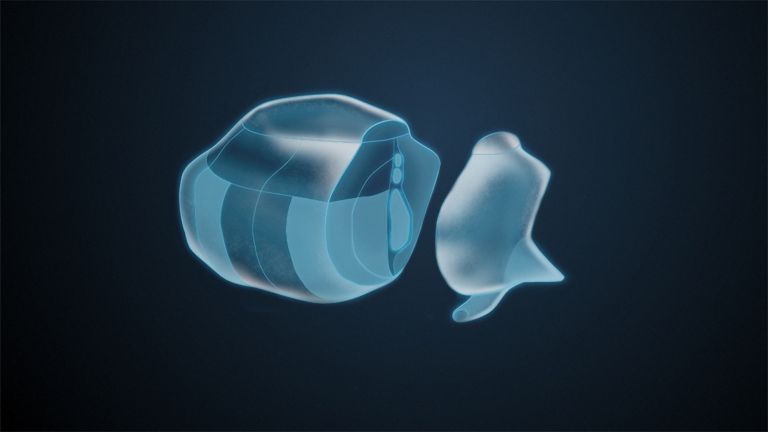

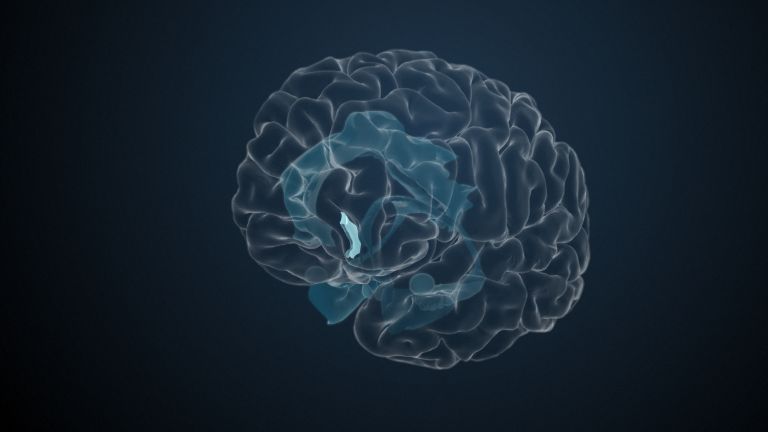

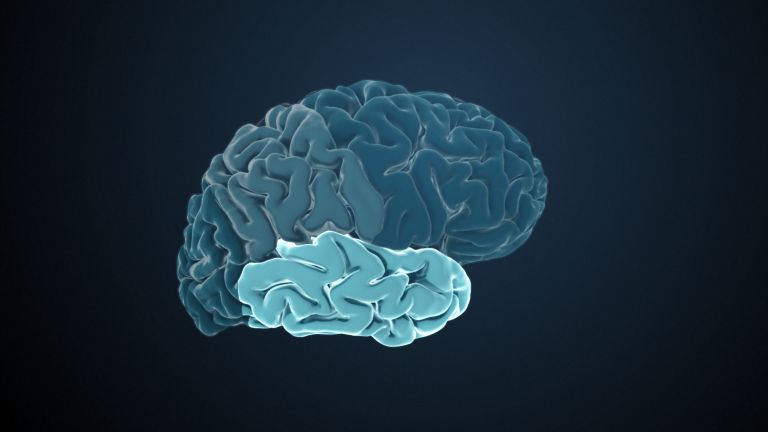

On a fresh brain section, the pale nucleus – the globus pallidus, or pallidum for short –lives up to its name: Especially when compared to the putamen, which lies next to it, it appears rather pale. The pallidum owes its striking colorlessness to many large, pigment-poor nerve cells. As part of the basal ganglia, it plays an important role in voluntary motor function – and does so in a highly complex manner.

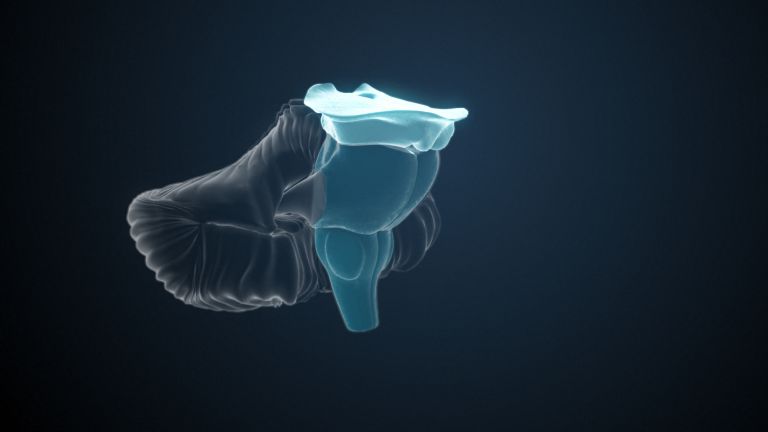

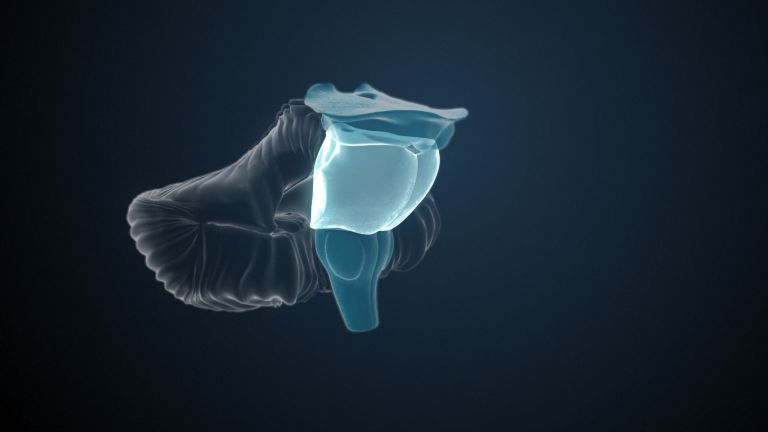

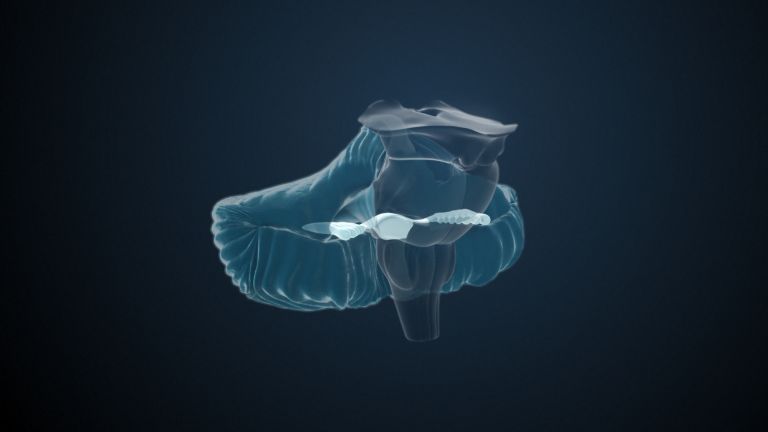

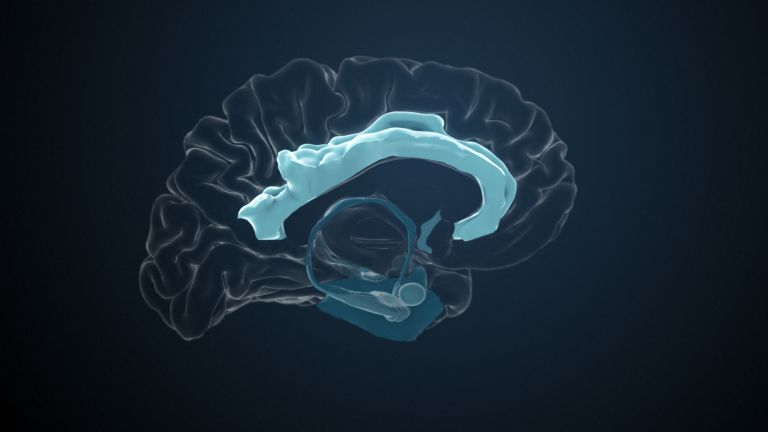

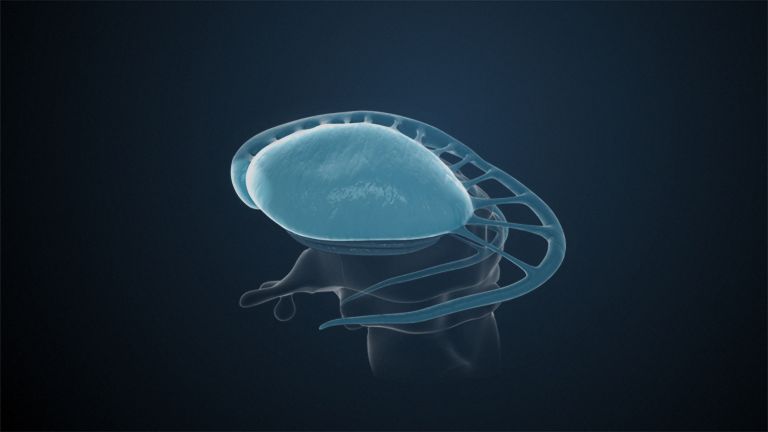

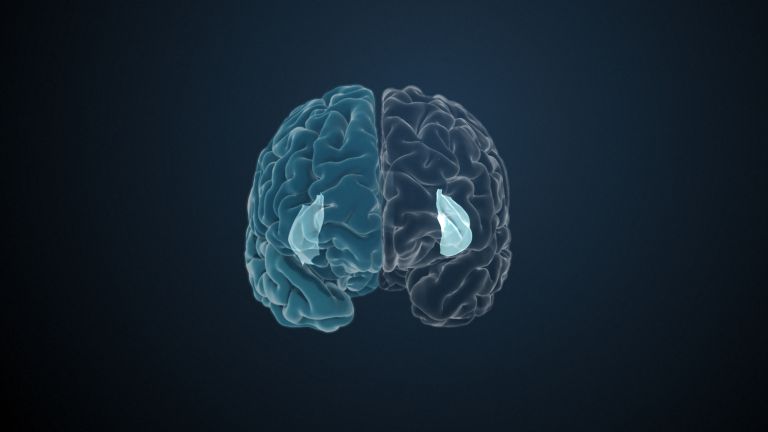

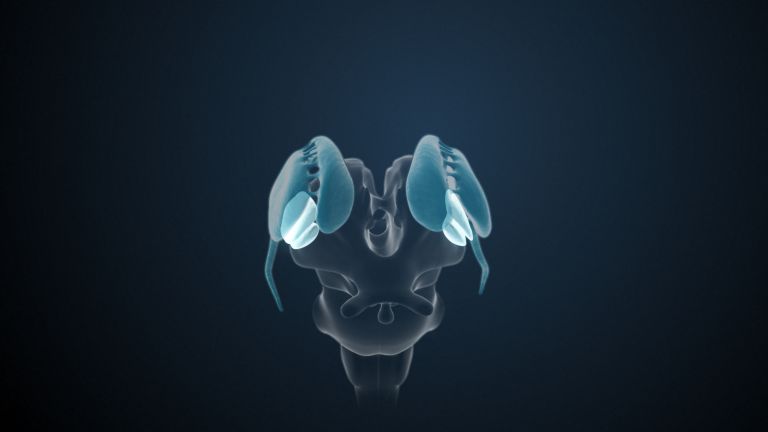

The globus pallidus consists of an inner part – the globus pallidus internus – and an outer part – the globus pallidus externus – which are separated from each other by a thin layer of white matter. Topographically speaking, it nestles closely against the putamen. Functionally and embryologically, however, the putamen and pallidum are very different. In fact, the globus pallidus is a scattered part of the diencephalon, more precisely – the ventral thalamus – which has been pushed to the side by the fibers of the internal capsule. And so it is also the diencephalon to which the pale nucleus sends the mass of its axons.

Recommended articles

Loops of inhibition and excitation

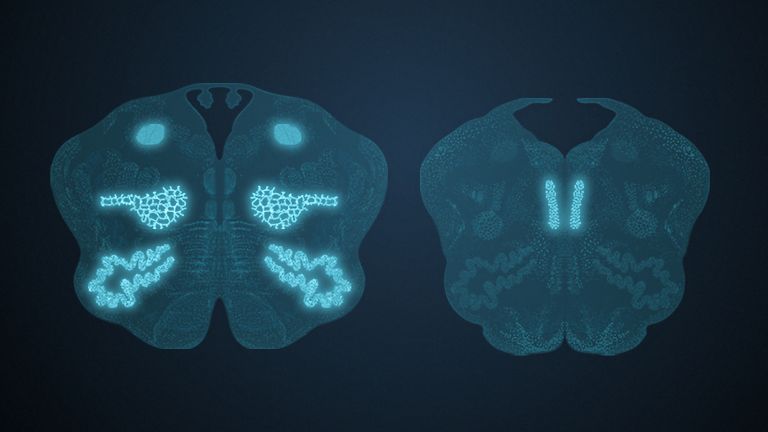

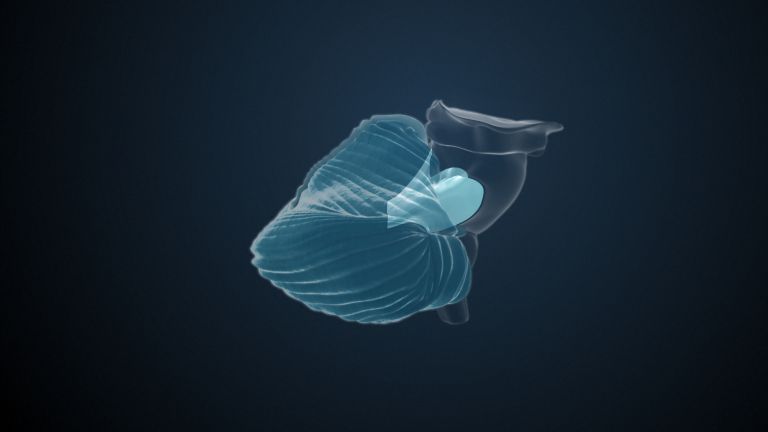

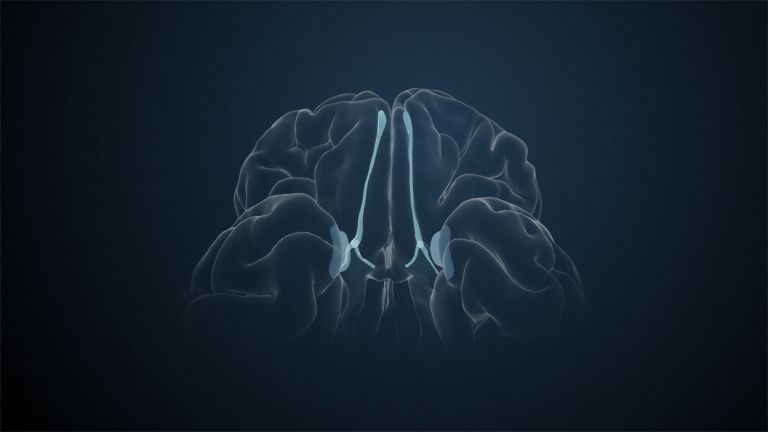

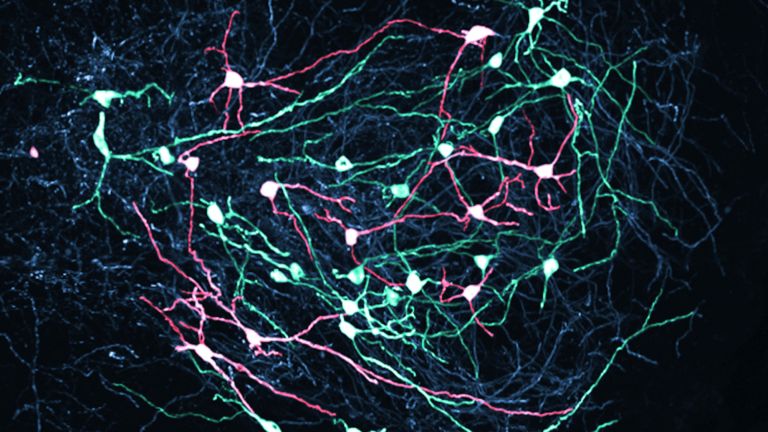

Voluntary movements are the most natural thing in the world; they come easily to us. However, once again, highly complex processes are at work behind the scenes. In this case, they manifest themselves in the interconnection of the pallidum: both the internal and external pallidum are influenced by nerve cells in the striatum, the uppermost area of the basal ganglia. The medium spiny neurons of the striatum are GABAergic, and GABA is an inhibitory neurotransmitter: the striatum therefore inhibits the activity of the pallidum. Its internal segment sends inhibitory axons to a nucleus of the thalamus, which in turn sends excitatory fibers to the cortex. This is where the loop closes, because the cortex excites the striatum.

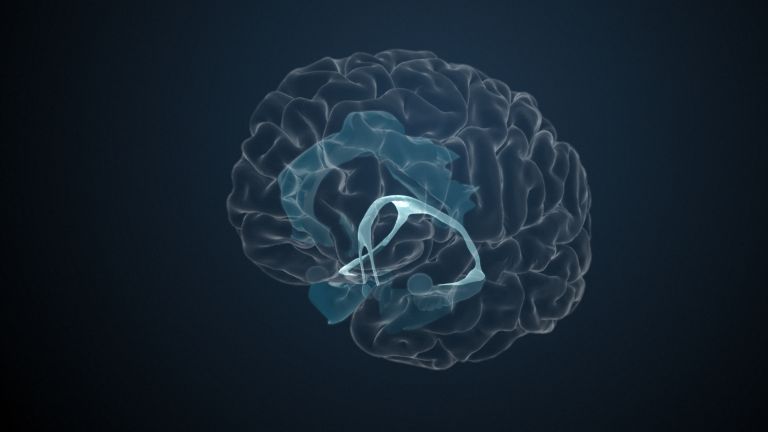

At the end, this loop creates positive feedback: the cortex fires into the system, thereby inhibiting the inhibition of the thalamic centers that excite it. This should actually lead to a feedback catastrophe, to excessive excitation of the cortical motor centers – if it weren't for a damper.

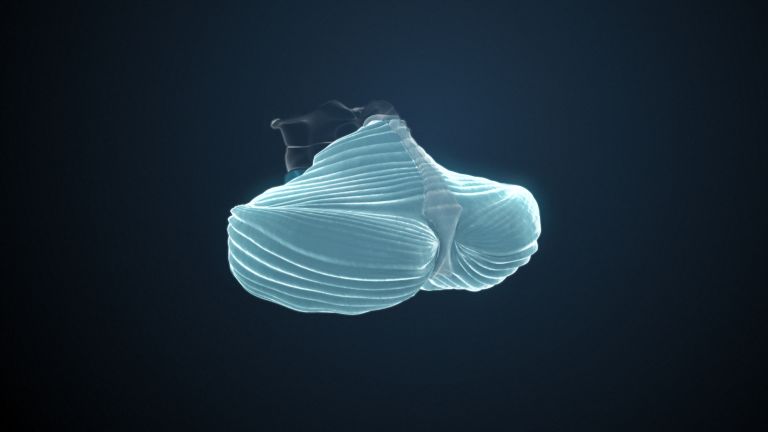

This damper consists of the external pallidum and the subthalamic nucleus, which is also located in the diencephalon. As mentioned above, the former is influenced by the inhibitory medium spiny neurons of the striatum and in turn inhibits the activity of the neurons in the subthalamic nucleus. However, the subthalamic nucleus sends excitatory fibers to the internal pallidum. This, as we mentioned, sends inhibitory fibers back to the thalamus, which excites the cortex. This loop is just as confusing as the first one, but a closer comparison reveals that there is one more inhibitory synapse at play here via the globus pallidus externus. Therefore it is a negative feedback loop that keeps the activity of the system in check.

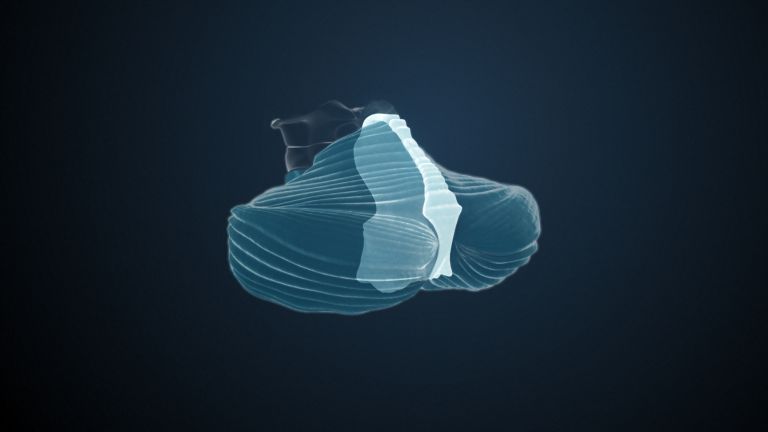

So, we can conclude that balance is crucial. This becomes most apparent when a “feedback catastrophe” actually occurs – for example, when the subthalamic nucleus is destroyed. Those affected suffer from uncontrollable, seizure-like, seemingly senseless movements of the extremities. This is called “ballism” (from the Greek “ballein”: to throw) and it looks as if the patients are trying to kick imaginary soccer balls or throw handballs. They can endanger themselves and others without being able to control their movements.

First published on August 23, 2011

Last updated on November 28, 2025