The Ventricular System

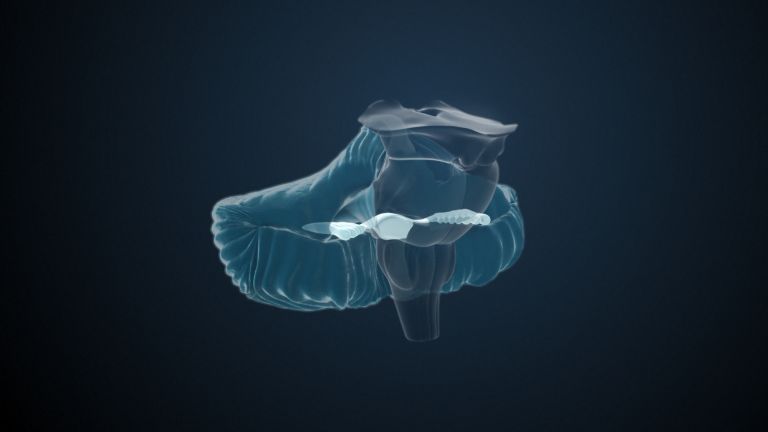

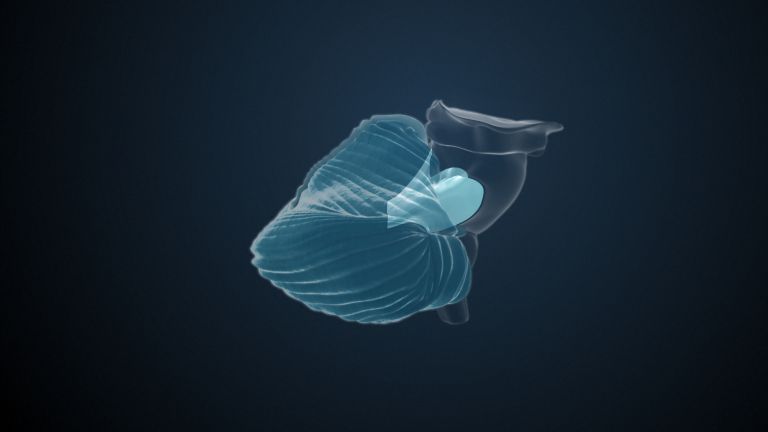

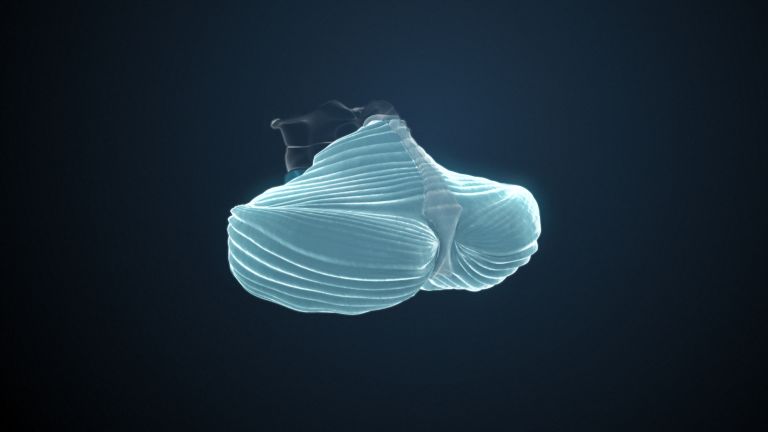

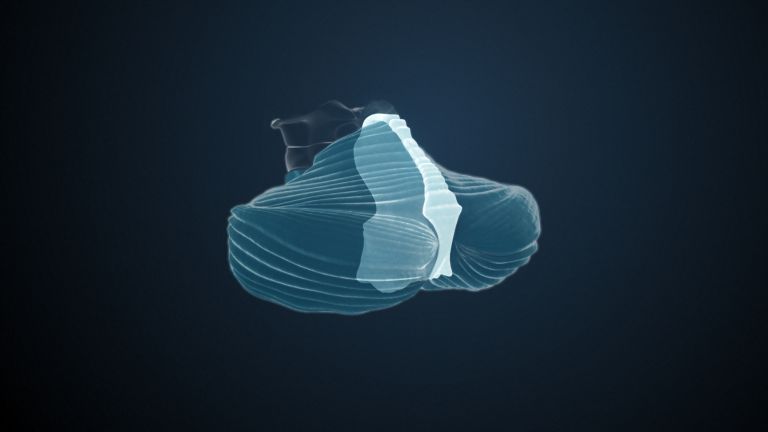

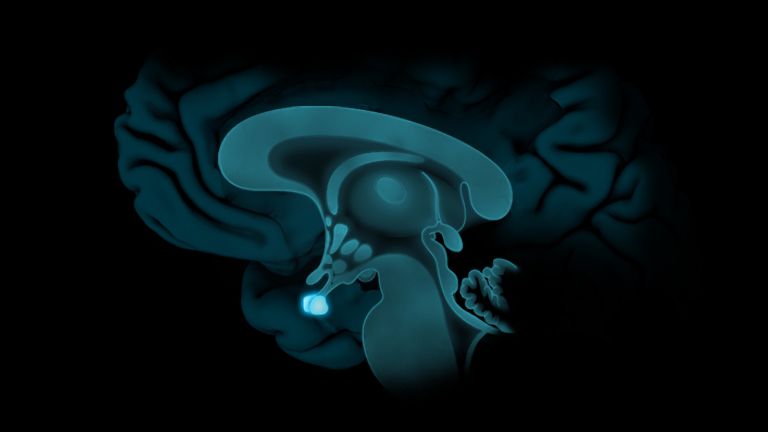

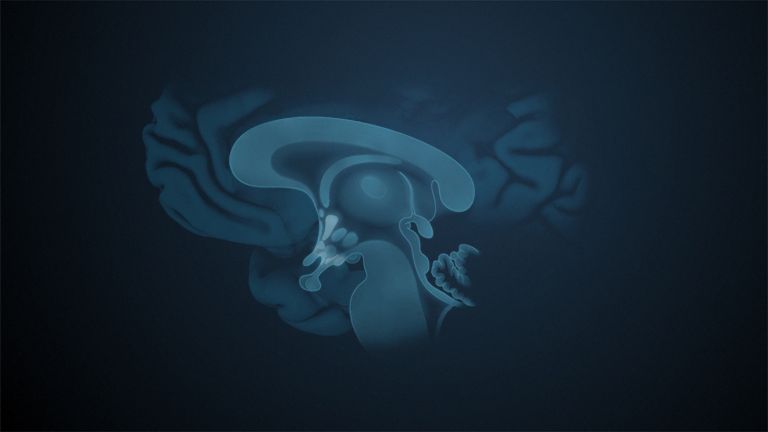

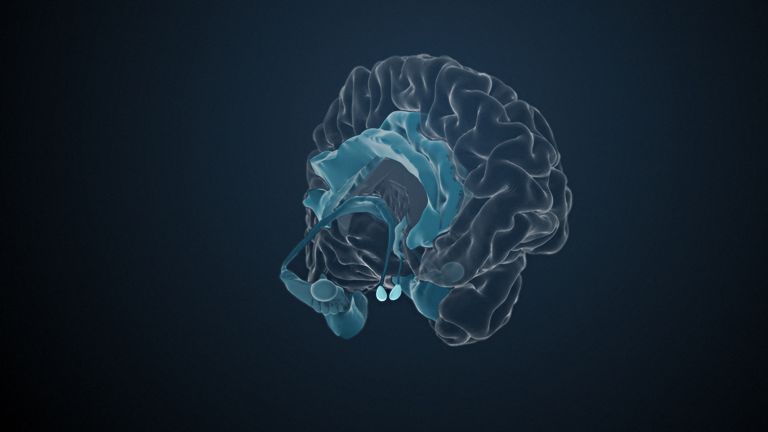

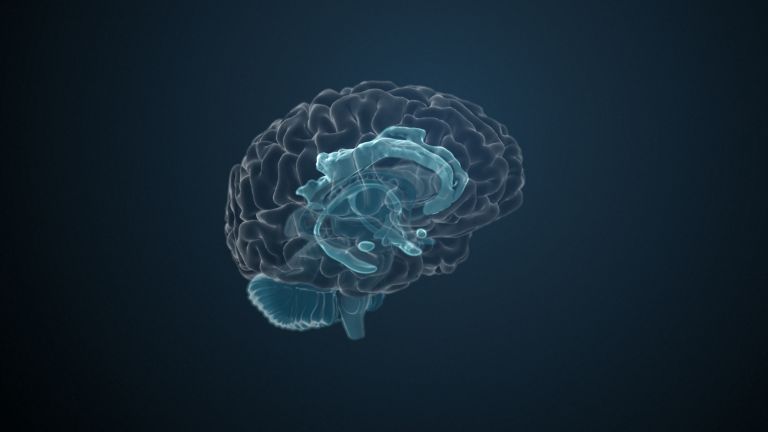

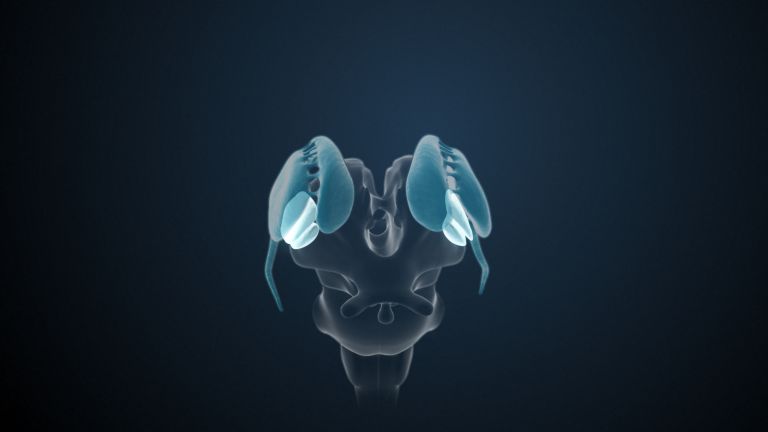

Anyone seeing what lies hidden deep within our brain for the first time may be amazed: a cave system filled with clear fluid and shaped by nature in a peculiar way. Is it an alien wearing a helmet? Or rather a human being with ram's horns?

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Jochen F. Staiger

Published: 20.09.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

The cavity system inside our brain consists of four interconnected chambers, the Ventricular system They are filled with cerebrospinal fluid, a clear, low-protein and almost cell-free liquid. It serves to mechanically cushion the central nervous system and facilitate humoral communication.

Ventricular system

A system of cavities in the brain filled with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). This provides protection, nutrition, homeostasis, and waste removal for the brain.

For diagnostic purposes, the doctor can extract Cerebrospinal fluid from the subarachnoid space via a lumbar puncture. To do this, he inserts a long needle between the third and fourth lumbar vertebrae. More rarely – only if a lumbar puncture is not possible – he punctures the external cerebrospinal fluid space directly on the skull.

This sounds very unpleasant, but it can be worthwhile in order to confirm a diagnosis and develop a specific treatment plan on this basis. For example, cerebrospinal fluid is an excellent way to detect inflammation of the central nervous system and the meninges: the fluid then contains more cells and proteins than normal, including white blood cells. Occasionally, bacterial pathogens are also found directly in the cerebrospinal fluid. In the autoimmune disease multiple sclerosis, antibodies, specifically immunoglobulin G, accumulate in the cerebrospinal fluid. In the case of a tumor, cancer cells can also be detected.

The external appearance of the cerebrospinal fluid also reveals a lot: in the case of meningitis, for example, the fluid is cloudy colored. Bloody cerebrospinal fluid is an indication of an often-fatal subarachnoid hemorrhage, in which blood vessels in the outer cerebrospinal fluid space have ruptured.

Cerebrospinal fluid

liquor cerebrospinalis

A clear fluid that fills the ventricular system and bathes the brain and spinal cord in the subarachnoid space, protecting them from impact. Three to five times a day, 100 to 160 ml of fluid is renewed by the choroid plexus. Certain diseases are reflected in the composition of the cerebrospinal fluid.

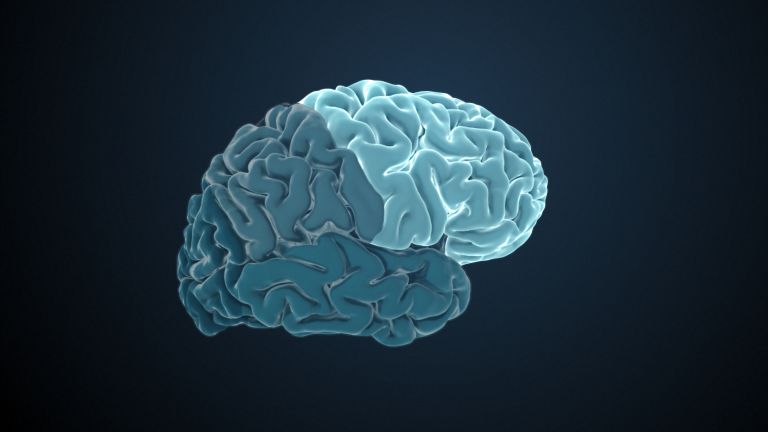

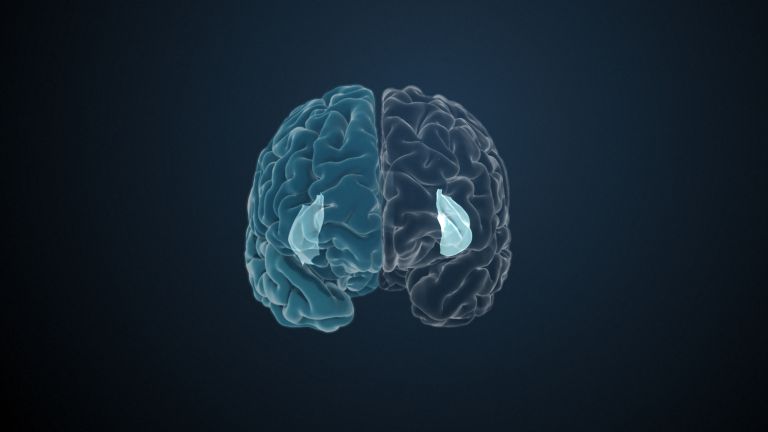

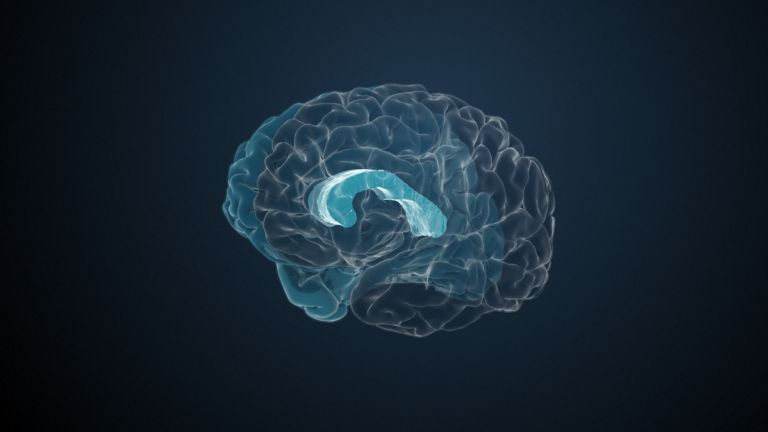

Is this thing really part of my brain? That's often the first thought that comes to mind when looking at images of the Ventricular system You're not quite sure whether it's an April Fool's joke or an inkblot test at the psychologist's office. But no, honestly: the inside of all our brains is partly hollow, and the cavity system actually resembles an alien wearing a helmet! And that's not all: structures with unusual shapes and unique names extend from its chambers – the Bochdalek's flower basket, for example. A quirk of nature? Of course not, because the ventricular system has various functions.

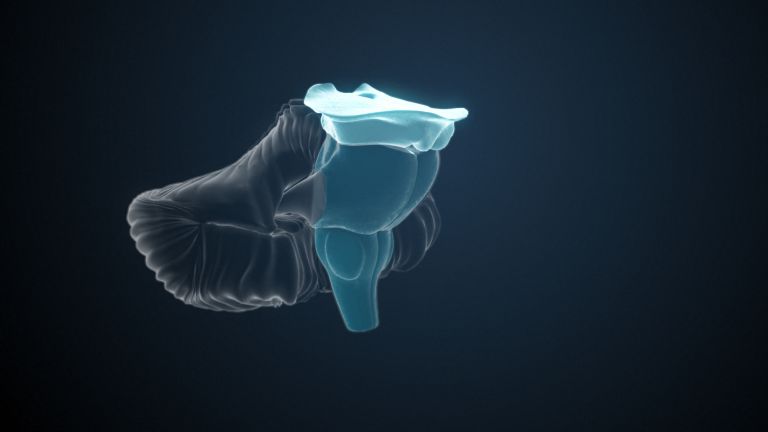

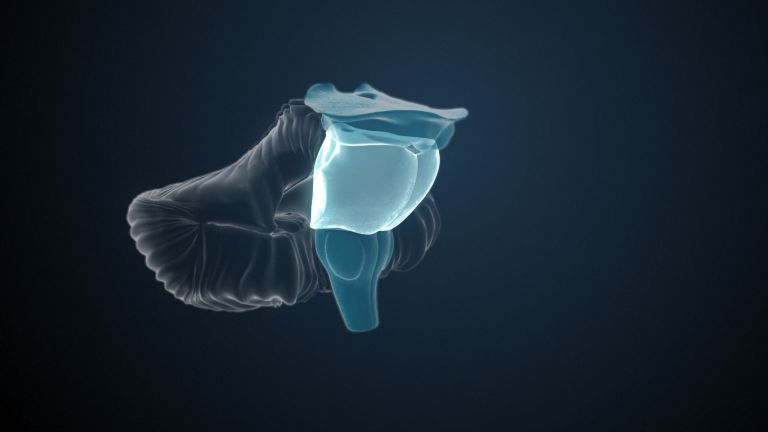

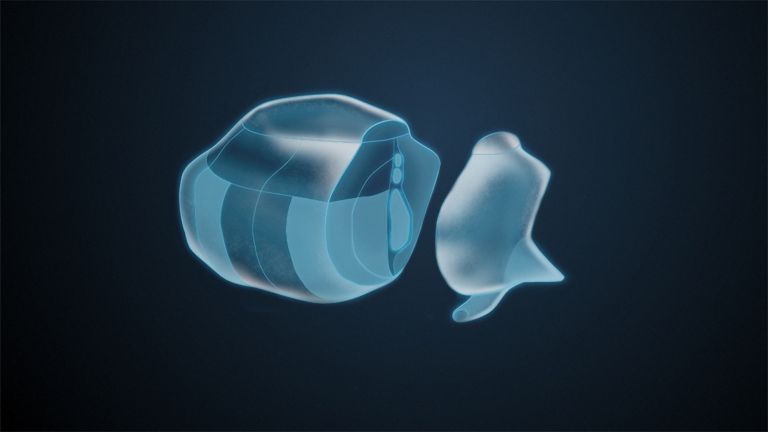

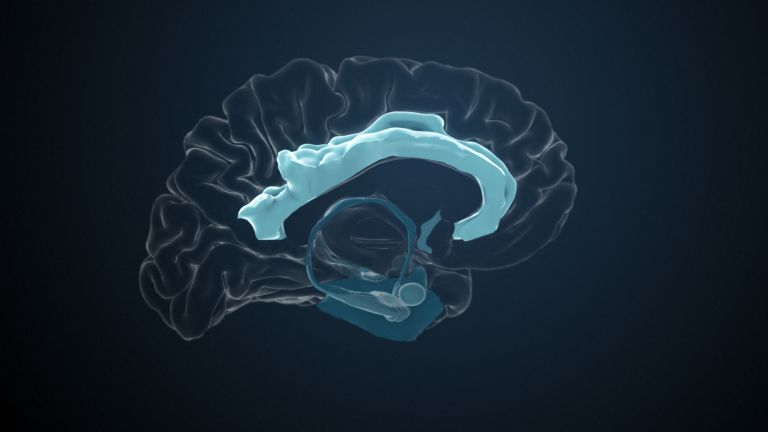

Let's take a closer look at the alien: a flattened head with eyes and an insect-like snout, an unusually long, thin, curved neck on a puny upper body with two scrawny arms and a protruding helmet on its head – this is how a cast of the ventricular system is presented in textbooks. Viewed prosier, it consists of four cavities that are connected to each other and filled with a clear fluid, the Cerebrospinal fluid (liquor cerebrospinalis). This fluid not only fills the ventricles inside, but also envelops the brain and Spinal cord on the outside, forming an effective buffer between the hard skull bone and the soft brain. There are no more than 150 milliliters of fluid in this cerebrospinal fluid system. Anything more than that would be unhealthy, or in other words, a hydrocephalus.

Ventricular system

A system of cavities in the brain filled with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). This provides protection, nutrition, homeostasis, and waste removal for the brain.

Cerebrospinal fluid

liquor cerebrospinalis

A clear fluid that fills the ventricular system and bathes the brain and spinal cord in the subarachnoid space, protecting them from impact. Three to five times a day, 100 to 160 ml of fluid is renewed by the choroid plexus. Certain diseases are reflected in the composition of the cerebrospinal fluid.

Spinal cord

medulla spinalis

The spinal cord is the part of the central nervous system located in the spine. It contains both the white matter of the nerve fibers and the gray matter of the cell nuclei. Simple reflexes such as the knee-jerk reflex are already processed here, as sensory and motor neurons are directly connected. The spinal cord is divided into the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral spinal cord.

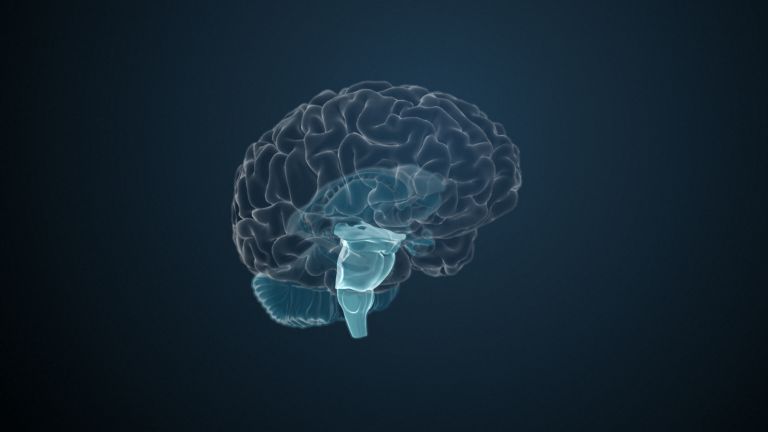

Structure and location

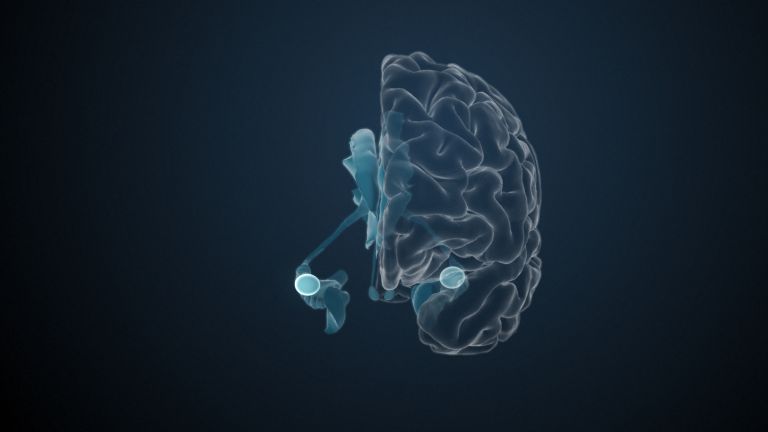

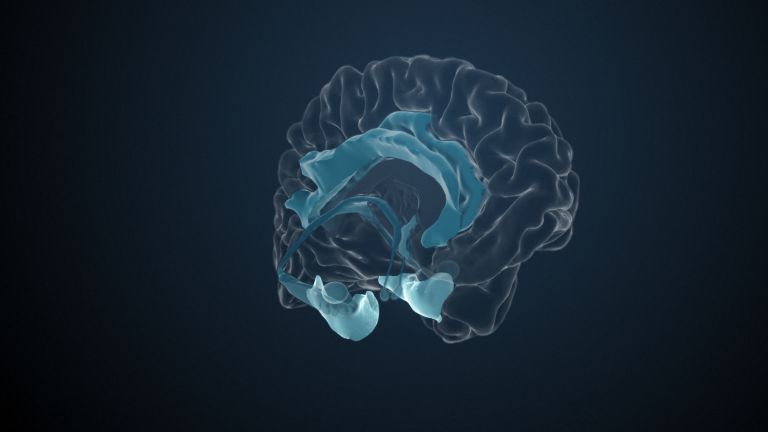

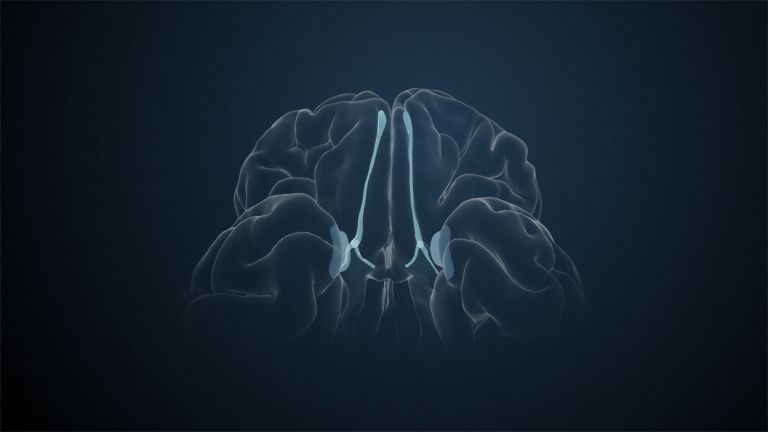

The Ventricular system consists of four chambers, which can be assigned to individual sections of the brain and are numbered with Roman numerals. The two lateral ventricles, numbered I and II, are located in the two hemispheres. They correspond to the helmet of the alien but are often compared to a horn in textbooks. Both chambers are divided into the expansive anterior horn (cornu frontale) in the frontal lobe, the narrower, arched middle part (pars centralis) in the parietal lobe, the small, backward-facing posterior horn (cornu occipitale) in the occipital lobe, and the lateral, forward-running inferior horn (cornu temporale) in the Temporal lobe This borders the Hippocampus at the bottom, while the other sections are bordered by the Corpus callosum at the top and the thalamus at the bottom.

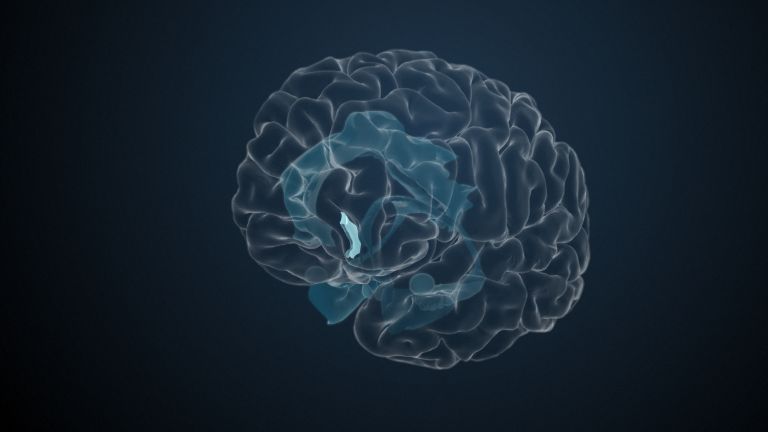

The third ventricle is a narrow, high, slit-shaped space. It forms the head of the alien and can be assigned to the Diencephalon. It abuts the thalamus, epithalamus, and Hypothalamus on the side. Where the right and left thalamus meet – at the interthalamic adhesion – there is a round recess in the third ventricle: the alien's Eye. The cavity ends in four narrow, elongated bulges – two in the alien's face and two at the back of its head.

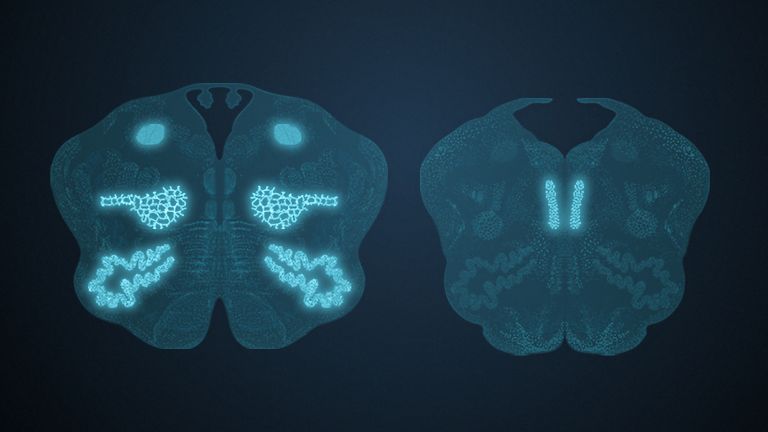

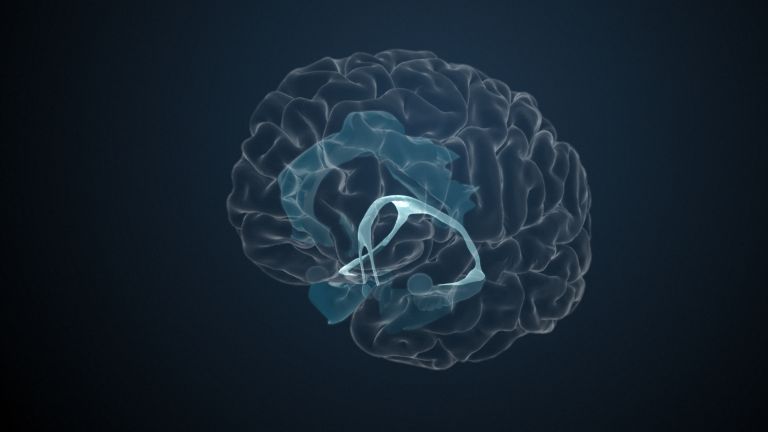

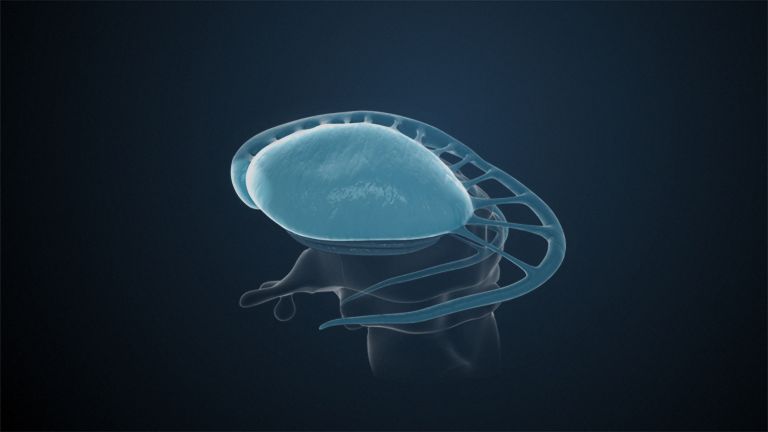

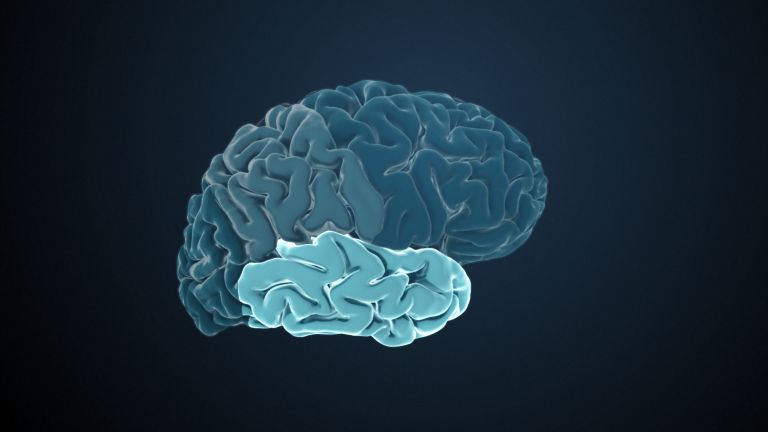

Finally, the fourth ventricle lies between the Brain stem – more precisely, the Medulla oblongata and Pons – on the one hand and the Cerebellum on the other. It forms the body of the alien with its two little arms. At their open ends, the aperturae laterales, they open onto the external Cerebrospinal fluid space between the inner and middle meninges – the aforementioned “buffer” to the skull bone. Another such connection is formed by the apertura mediana – the alien's stubby tail, so to speak. The fourth ventricle continues downwards into the central canal of the spinal cord.

The four ventricles are connected to each other. Two short bulges, the foramina interventricularia, connect each lateral ventricle to the third ventricle. Whether ram's horn or alien helmet: here they are attached to the alien's head. Its long neck is actually the “water pipe of the midbrain”, the aqueductus mesencephali. Through it, the cerebrospinal fluid flows from the third to the fourth ventricle.

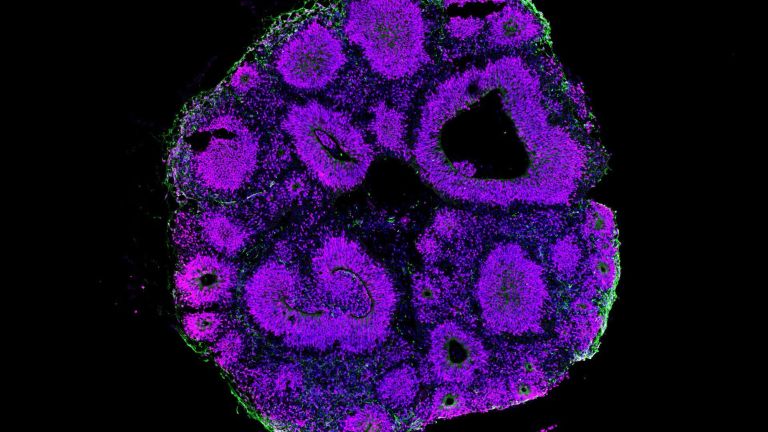

The unusual structures of the ventricular system develop during embryonic development after the neural tube – the origin of the central nervous system – has bulged out to form vesicles. This first creates a single cavity. However, because the different parts of the brain grow at different speeds and rates, it initially divides into three chambers, then into five. This is how the alien in the brain gradually develops.

This alien, this ventricular system, had a very special meaning for the ancient Greeks: here, according to unanimous opinion, was the seat of the human mind, even of the soul. The actual brain, on the other hand, was considered worthless by the ancient Greeks. This opinion persisted into the Middle Ages.

Ventricular system

A system of cavities in the brain filled with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). This provides protection, nutrition, homeostasis, and waste removal for the brain.

lateral

A positional term – lateral means "towards the side." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction at right angles to the neural axis, i.e., to the right or left.

frontal

An anatomical position designation – frontal means "towards the forehead," i.e., at the front.

posterior

A positional term – posterior means "towards the back, located at the rear." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction towards the tail.

inferior

An anatomical position designation – inferior means located further down, the lower part.

Temporal lobe

Lobus temporalis

The temporal lobe is one of the four lobes of the cerebrum and is located laterally (on the side) at the bottom. It contains important areas such as the auditory cortex and parts of Wernicke's area, as well as areas for higher visual processing; deep within it lies the medial temporal lobe with structures such as the hippocampus.

Hippocampus

The hippocampus is the largest part of the archicortex and an area in the temporal lobe. It is also an important part of the limbic system. Functionally, it is involved in memory processes, but also in spatial orientation and learning. It comprises the subiculum, the dentate gyrus, and the Ammon's horn with its four fields CA1-CA4.

Changes in the structure of the hippocampus due to stress are associated with chronic pain. The hippocampus also plays an important role in the amplification of pain through anxiety.

Corpus callosum

As the largest commissure (connection in the brain), the corpus callosum connects the two cerebral hemispheres. It consists of 200-250 million nerve fibers and serves to exchange information.

Diencephalon

The diencephalon (midbrain) includes the thalamus and hypothalamus, among other structures. Together with the cerebrum, it forms the forebrain. The diencephalon contains centers for sensory perception, emotion, and the control of vital functions such as hunger and thirst.

Hypothalamus

The hypothalamus is considered the center of the autonomic nervous system, meaning it controls many motivational states and regulates vegetative aspects such as hunger, thirst, and sexual behavior. As an endocrine gland (which, unlike an exocrine gland, releases its hormones directly into the blood without a duct), it produces numerous hormones, some of which inhibit or stimulate the pituitary gland to release hormones into the blood.In this function, it also plays an important role in the response to pain and is involved in pain modulation.

Eye

bulbus oculi

The eye is the sensory organ responsible for perceiving light stimuli – electromagnetic radiation within a specific frequency range. The light visible to humans lies in the range between 380 and 780 nanometers.

Brain stem

truncus cerebri

The "trunk" of the brain, to which all other brain structures are "attached," so to speak. From bottom to top, it comprises the medulla oblongata, the pons, and the mesencephalon. It transitions into the spinal cord below. It is a center for vital functions such as breathing and heartbeat and contains ascending and descending pathways between the cerebrum, cerebellum, and spinal cord.

Medulla oblongata

Area of the brain that transitions into the spinal cord. The medulla oblongata comprises nerve pathways between the spinal cord and higher brain regions, as well as numerous core areas with functions that are in some cases vital, such as breathing, heartbeat, and certain reflexes.

Pons

pons

Area in the brain stem between the medulla oblongata and the mesencephalon. It acts as a switching station for many nerve pathways between the brain and spinal cord and contains numerous nuclei, including cranial nerves and those involved in controlling motor function in cooperation with the cerebellum.

Cerebellum

Cerebellum

The cerebellum is an important part of the brain, located at the back of the brain stem and below the occipital lobe. It consists of two cerebellar hemispheres covered by the cerebellar cortex and plays an important role in motor processes, among other things. It develops from the rhombencephalon.

Cerebrospinal fluid

liquor cerebrospinalis

A clear fluid that fills the ventricular system and bathes the brain and spinal cord in the subarachnoid space, protecting them from impact. Three to five times a day, 100 to 160 ml of fluid is renewed by the choroid plexus. Certain diseases are reflected in the composition of the cerebrospinal fluid.

Recommended articles

Circulation of cerebrospinal fluid

Our skull contains a total of about 150 milliliters of cerebrospinal fluid, 30 inside and 120 outside the brain. The outer cerebrospinal fluid space has an amazing effect: by enveloping the brain, it reduces its effective weight on the bones from 1500 grams to just 50 grams.

Every day, the body produces about half a liter of cerebrospinal fluid, meaning that the entire contents are replaced about three times a day. If more is produced than is absorbed, the cerebrospinal fluid accumulates in the skull, leading to external hydrocephalus. In infants, the still flexible skull begins to enlarge. However, the narrow aqueduct between the third and fourth ventricles can also become blocked, causing only the Ventricular system I-III to expand – resulting in what is known as internal hydrocephalus. In either case, the result is severe headaches and potential brain dysfunction.

Computed tomography and Magnetic resonance imaging can be used to easily visualize the ventricular system. The physician can then use cross-sectional images to assess whether it is larger than normal. In the case of hydrocephalus, the physician will attempt to restore normal cerebrospinal fluid drainage using a drain.

Cerebrospinal fluid

liquor cerebrospinalis

A clear fluid that fills the ventricular system and bathes the brain and spinal cord in the subarachnoid space, protecting them from impact. Three to five times a day, 100 to 160 ml of fluid is renewed by the choroid plexus. Certain diseases are reflected in the composition of the cerebrospinal fluid.

lateral

A positional term – lateral means "towards the side." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction at right angles to the neural axis, i.e., to the right or left.

Ventricular system

A system of cavities in the brain filled with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). This provides protection, nutrition, homeostasis, and waste removal for the brain.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging scanner

A device used by medical professionals for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI is an imaging technique used to diagnose malformations in various tissues or organs of the body. This method is particularly effective for imaging parts of the body that contain a lot of water. Patients are placed in a tube (scanner) and exposed to a strong magnetic field. However, they are not exposed to X-rays or other forms of ionizing radiation.

First published on August 8, 2011

Last updated on August 5, 2025