Alzheimer's disease

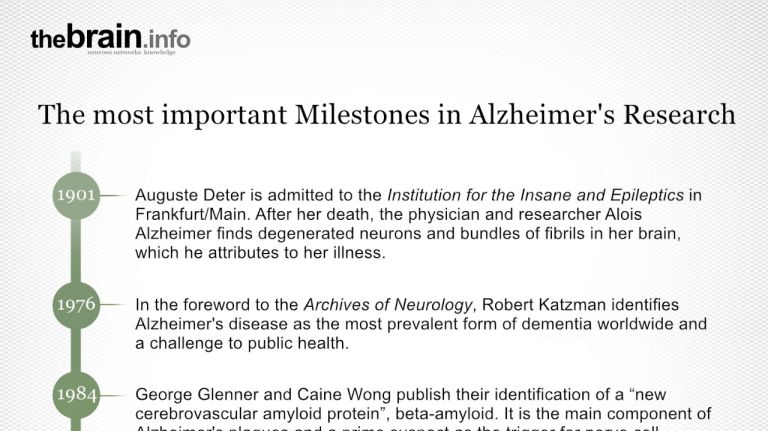

“Mental illnesses are brain diseases.” This credo, formulated in 1845 by Berlin neurologist Wilhelm Griesinger, was also shared by Alois Alzheimer. As a researcher and psychiatrist – known as the “mad-doctor with a microscope” – he discovered in 1906 the biological traces of the dementia disease named after him: plaques between the cells and thread-like structures (fibril bundles) in the cells. However, when he reported on this at a conference, his lecture received little attention – many of his contemporaries did not see the brain as the cause of mental illness, but rather the soul. They preferred to argue about Freud's psychoanalysis rather than look at Dr. Alzheimer's brain sections.

Today, there is a similar conflict: some claim that Alzheimer's is not a disease that can be cured in principle, but rather a normal part of the aging process. They argue that further research funding should be spared and the money better spent on improving care. Others point to astonishing discoveries and are placing their hopes in science more than ever.

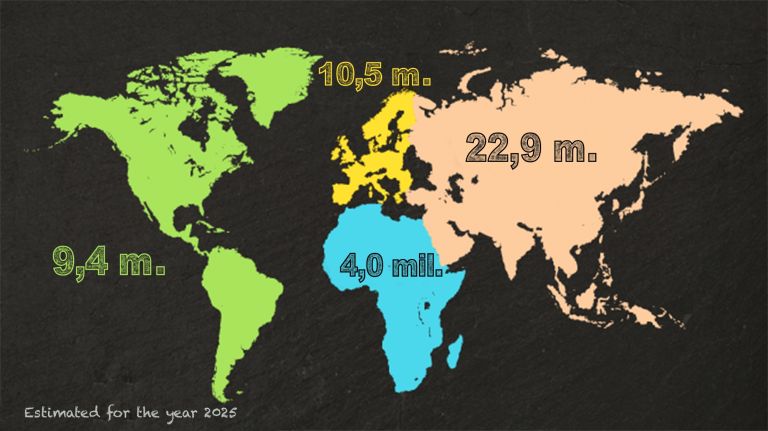

Our focus highlights both sides: the efforts of research and its spectacular successes – because a breakthrough may not be far off – but also the almost unstoppable progression of dementia and the changes it brings for patients and their families. The disease currently affects nearly 60 million people worldwide, and this figure is expected to rise to over 150 million by 2050. This means that decisions with far-reaching consequences for the future need to be made today.