Alzheimer's from the Inside

Alzheimer's disease is still stigmatized. Perhaps that is why patients rarely speak out in the media. Here is a visit to someone affected by the disease.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Anja Schneider

Published: 20.10.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

- In the early stages of Alzheimer's disease, those affected usually sense that their performance is declining.

- Even for some doctors, it is difficult to recognize the symptoms at first, either because patients downplay them or because they are not yet so severe that they can only be detected through extensive neuropsychological testing. Diagnostic classification also plays an important role. Other treatable causes of memory impairment must be ruled out, such as depression.

- The medical diagnosis provides clarity. Patients now know the reasons for their forgetfulness, and the accusations from those around them usually subside. On the other hand, patients sometimes feel stigmatized by the diagnosis.

- Patients must learn to accept help. The burden on relatives grows.

- Friends and acquaintances often withdraw after an Alzheimer's diagnosis becomes known. This exacerbates the suffering of patients and their relatives.

- Society is only gradually becoming aware of how debilitating the stigmatization of Alzheimer's disease is.

Alzheimer's disease

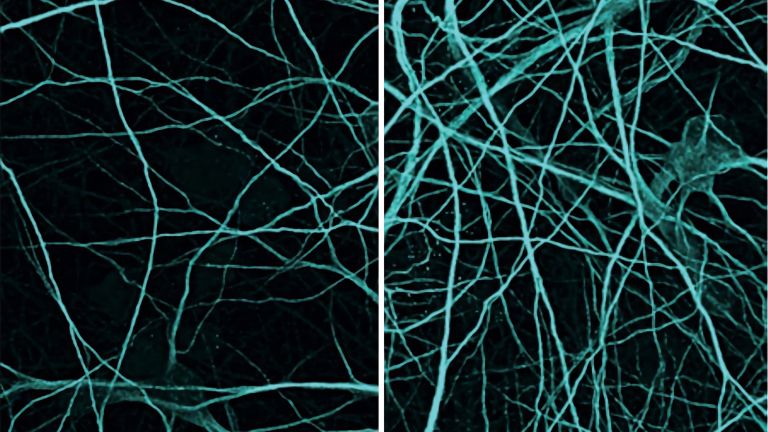

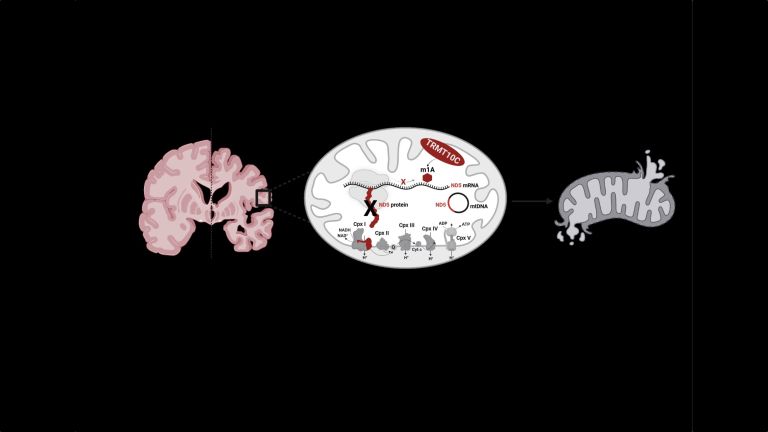

Morbus Alzheimer

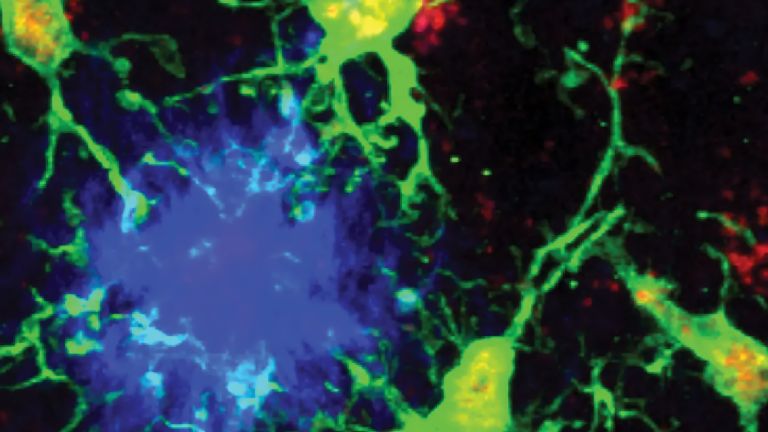

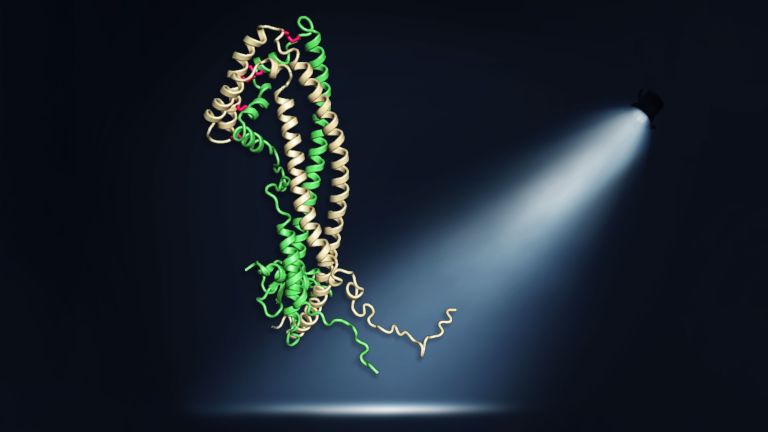

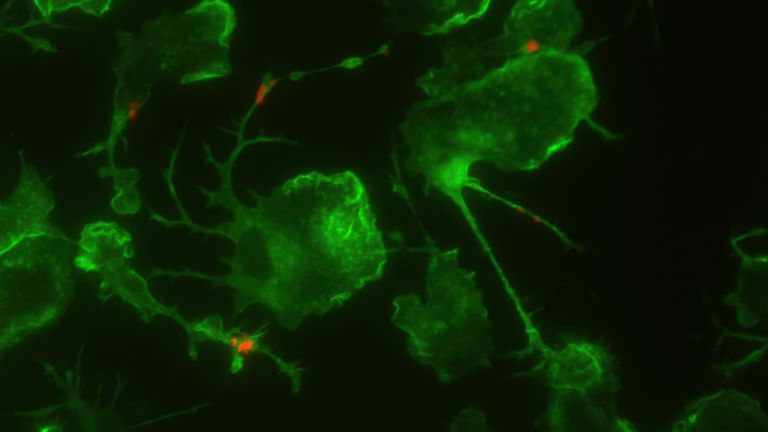

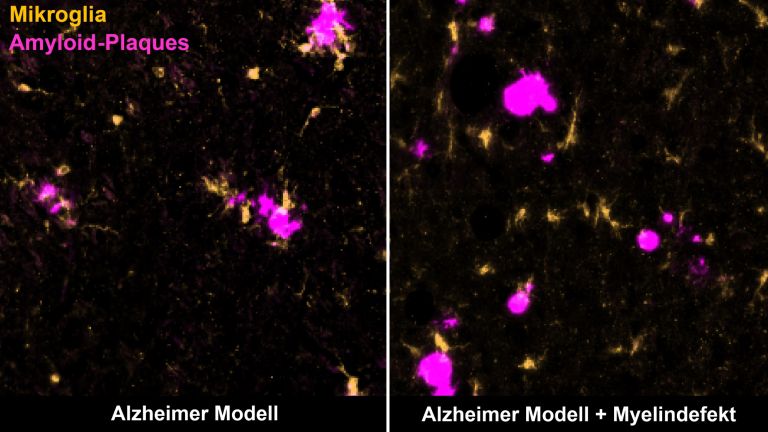

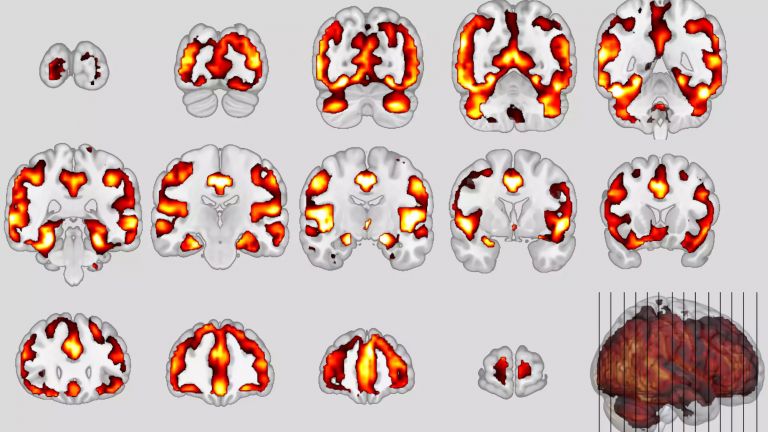

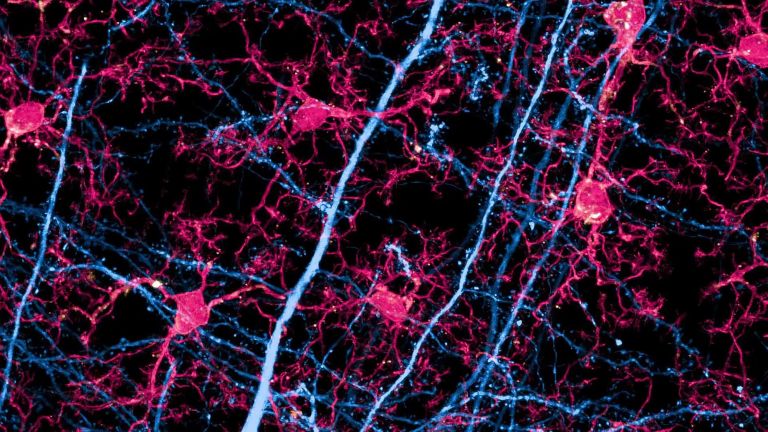

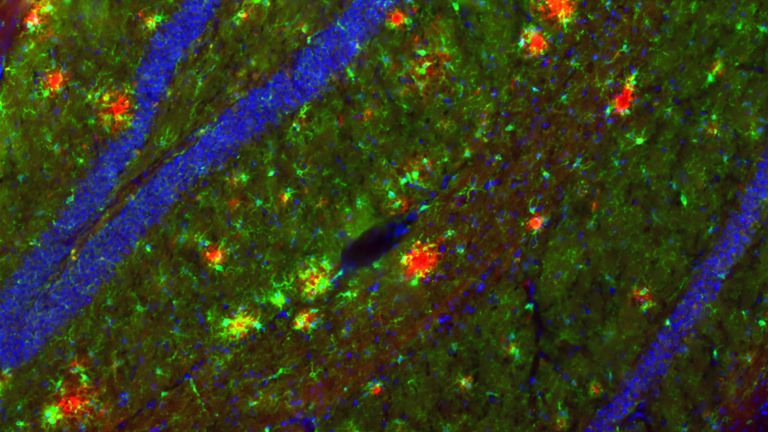

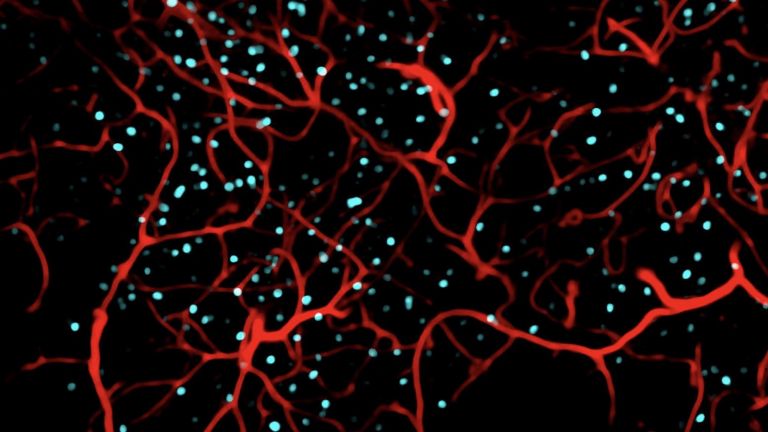

Alzheimer's disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by cortical atrophy, nerve cell loss, synapse loss, and deposits of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, leading to dementia and loss of function. Early symptoms include memory problems, speech disorders, executive deficits, depressive moods, and subtle personality changes. As the disease progresses, global cognitive impairment, aphasia, agnosia, apraxia, and behavioral abnormalities such as apathy, restlessness, and sleep disorders occur. The disease was first described in 1907 by Alois Alzheimer.

In his book Alzheimer's and Me, American psychologist Richard Taylor writes about his life with the disease. This book is remarkable in several ways. Few people affected by Alzheimer's disease speak out in public, as the stigma attached to the disease is still too great: those affected are easily considered completely incompetent. And certainly no one writes an entire book in which, despite memory problems and word-finding difficulties, they describe their situation eloquently, humorously, and with great reflection. Among other things, Richard Taylor provides very candid insights into the fears that can plague Alzheimer's patients. He describes his existential fear of the end, which slowly creeps into his heart and mind. “Not the death of my person, but rather the end of the being that I know and that others have known.” He also talks about the humiliation of having to accept help from others and the fear of making mistakes. In addition, we learn how he tries to cope with the disease through his thinking and writing.

Alzheimer's disease

Morbus Alzheimer

Alzheimer's disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by cortical atrophy, nerve cell loss, synapse loss, and deposits of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, leading to dementia and loss of function. Early symptoms include memory problems, speech disorders, executive deficits, depressive moods, and subtle personality changes. As the disease progresses, global cognitive impairment, aphasia, agnosia, apraxia, and behavioral abnormalities such as apathy, restlessness, and sleep disorders occur. The disease was first described in 1907 by Alois Alzheimer.

An unrenovated house in Berlin's Prenzlauer Berg district. We go up a few floors. “Come in.” Rainer Fritsch opens the door to a comfortably furnished apartment in an old building. His wife stands in the kitchen, reserved and somewhat uncertain. We have an hour for our conversation. Then Birgit Fritsch has to leave for a group meeting.

She manages the journey there independently, including the tram. This is by no means a matter of course. The 63-year-old suffers from Alzheimer's disease Orientation is generally one of the biggest problems for those affected, but Ms. Fritsch still manages to find her way around quite well. “I still know where I have to go,” she says in a pleasant Berlin dialect. But she immediately adds: “Well, I don't go anywhere on my own that I haven't been before.”

Her group meeting is a psychosocial meeting place. It is organized by the non-profit Alzheimer's Association Berlin, which was founded jointly by family caregivers of dementia patients and experts. People with memory problems come together here and do things together. Sometimes they go to the movies, for coffee, or, like today, to the museum. A trained professional accompanies the group.

Alzheimer's disease

Morbus Alzheimer

Alzheimer's disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by cortical atrophy, nerve cell loss, synapse loss, and deposits of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, leading to dementia and loss of function. Early symptoms include memory problems, speech disorders, executive deficits, depressive moods, and subtle personality changes. As the disease progresses, global cognitive impairment, aphasia, agnosia, apraxia, and behavioral abnormalities such as apathy, restlessness, and sleep disorders occur. The disease was first described in 1907 by Alois Alzheimer.

Struggling to find the right words

In personal conversation, you notice how Birgit Fritsch struggles with her memory. She struggles to find the right words. Her husband often takes over for her when she can no longer remember or express herself. For example, she has to think long and hard about the question of what job she used to do. She repeatedly looks to her husband for help, asking him to answer for her. “Tell her what you studied,” Mr. Fritsch tries to help her out. “Well, what was it again?” she asks, shrugging her shoulders. Not for the last time that day, she shifts nervously back and forth.

It's easy to get confused by this question. Mrs. Fritsch has had an eventful career, working as a chemist and in payroll accounting, among other things. In one of her last jobs, she worked in a toy store. “It wasn't so obvious at the time, but looking back, that's when the disease started,” recalls Rainer Fritsch. “The boss always made terrible accusations against my wife when she forgot something.” He had already noticed in everyday life that she was no longer able to operate the coffee machine. “I just didn't know how to do it anymore,” confirms his other half. She ultimately had to give up her last job, an office assistant position paying 400 euros, because she was increasingly unable to meet the demands.

Mental abilities decline

“In the early stages, those affected themselves feel that their mental abilities are declining,” says psychologist Christa Matter, managing director of the Alzheimer's Association Berlin e.V. “They find it increasingly difficult to store and retrieve new information in particular. Long-term memory, on the other hand, earlier memories, is not affected at first.”

Those around them often don't notice any changes. “Those affected still have a lot of knowledge at their disposal and are able to compensate for some mental deficits. They can still manage their affairs largely independently and live on their own.” However, the loss of mental abilities can affect the self-image of those affected, leading to insecurity and even depressive reactions.

A long odyssey to diagnosis

For the Fritsch couple, the time before the diagnosis was a period of great uncertainty and insecurity. Because he was unaware of the disease, Rainer Fritsch would occasionally reproach his wife for forgetting this or that. “I would sometimes start to cry,” recalls Birgit Fritsch.

The path to diagnosis was an odyssey from doctor to doctor. For a long time, doctors dismissed the suspicion of Alzheimer's and assumed it was depression, as this mental illness can also lead to memory problems. “For a long time, nothing seemed wrong with her when we talked,” says Rainer Fritsch, searching for an explanation. It was only after several weeks of observation and examination at a day clinic in mid-2010 that the diagnosis was made. “That's when the crying really started,” says Birgit Fritsch. But at some point, she began to accept the diagnosis. “I told myself that I'm definitely not the only one. And it is what it is. I can't change it.”

In some ways, things are easier for the Fritsch family today. They now know about the condition and have adapted to it together with their son. Mr. Fritsch helps his wife wherever he can, especially with the housework. At the same time, however, the condition has worsened since the first signs appeared. Birgit Fritsch can no longer go shopping. She also has difficulty with housework, including cooking. “Cooking doesn't work so well. We often have to work together now.”

Increasing memory and orientation problems

In the early days, she still resorted to one or two tricks. “I used to write things down on sticky notes.” For example, that she still had to go shopping. There were many notes at first. But at some point, that stopped. “She probably didn't feel like doing it anymore because she increasingly didn't know how to spell the words,” believes Rainer Fritsch. His wife is probably already in the middle stage of the disease. (On the progression of Alzheimer's disease ▸ Slowly forgetting)

At this stage, memory and orientation problems increase. “As a result, those affected are usually no longer able to cope with their lives on their own,” says Christa Matter. “They need help even with simple tasks, such as preparing meals, getting dressed, or personal hygiene.” They are now less and less able to form complete sentences and find it increasingly difficult to take in messages from others. "Early memories are also increasingly unavailable. Some no longer know whether they have children or when they got married.“

Birgit Fritsch has particular problems with things that happened relatively recently. ”She always asks me: What's happening today? Who's coming to visit us today?" says Rainer Fritsch. His wife starts to laugh; there is a lot of laughter this morning. But sometimes the cheerful façade cracks. For example, when Mrs. Fritsch reacts with complete incomprehension to the question of how old she is: “What am I?” At that moment, Mr. Fritsch looks very serious, and you can sense that his wife's memory problems still shock him. “Think about it,” he urges her. “What does he want to know now?” Birgit Fritsch asks back. “Your age.” She laughs. It's not the first time you get the feeling that she's trying to cover something up with her cheerfulness. “Over 60, definitely,” she says slowly. “Unfortunately, 63,” says Mr. Fritsch. “Well, that's not so bad.”

Alzheimer's disease

Morbus Alzheimer

Alzheimer's disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by cortical atrophy, nerve cell loss, synapse loss, and deposits of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, leading to dementia and loss of function. Early symptoms include memory problems, speech disorders, executive deficits, depressive moods, and subtle personality changes. As the disease progresses, global cognitive impairment, aphasia, agnosia, apraxia, and behavioral abnormalities such as apathy, restlessness, and sleep disorders occur. The disease was first described in 1907 by Alois Alzheimer.

Recommended articles

A burden for relatives too

While Birgit Fritsch seems to be taking her illness relatively calmly, you can see the pressure weighing on her husband in particular. He has to run the household, look after his wife, and still do his job. Sometimes he finds comfort in the thought that he still has it easier than many other relatives of Alzheimer's patients. He tells of a patient who always becomes very depressed or even aggressive when invited to a social gathering because she doesn't understand much of the conversation and feels excluded. His wife, on the other hand, has not changed much in terms of personality. “I can tell by the fact that she still enjoys being in company.”

However, she has become a little restless and is constantly tidying up the apartment. Magazines and documents are no longer in their place. “If I'm not careful, they'll be somewhere else.” “After all, I want to read some of the magazines, too,” Birgit Fritsch replies with a smile. Reading is still going quite well. She spends hours browsing through magazines – usually women's magazines, but also Der Spiegel, which is a real passion of hers. While reading, she underlines a lot, probably to help her concentrate better, her husband believes. “Then I still remember a little bit after reading an article.” Birgit Fritsch jumps up and wants to show her magazines, but can't find them.

Open communication about the disease is rare

Alzheimer's still carries a stigma. Few Alzheimer's patients are as open about their disease as Birgit Fritsch. She has been meeting up with a group of women to exercise for years, even after her diagnosis. “They know about it,” she says, referring to her illness. “And if I'm not feeling so good sometimes, well, that's just the way it is. Then I just do what I can.”

When the interview is over and Ms. Fritsch has to leave, they both look for her wallet. This is a tiresome topic in the Fritsch household. Just a week earlier, Birgit Fritsch lost her wallet with her severely disabled ID card. Yesterday, they had a new ID card issued. Even though the Fritschs deal with the disease admirably, it is by no means easy. It's a struggle every day.

Further reading

- Taylor, Richard: Alzheimer's and Me. Living with Dr. Alzheimer's in My Head, Göttingen, 2025.

First published on September 20, 2013

Last updated on November 11, 2025