Alzheimer's – a Disease makes History

In over 100 years, Alzheimer's disease has developed from a marginal phenomenon into a global social problem. Many possible risk factors are now known. However, there is still no cure.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Anja Schneider

Published: 20.10.2025

Difficulty: easy

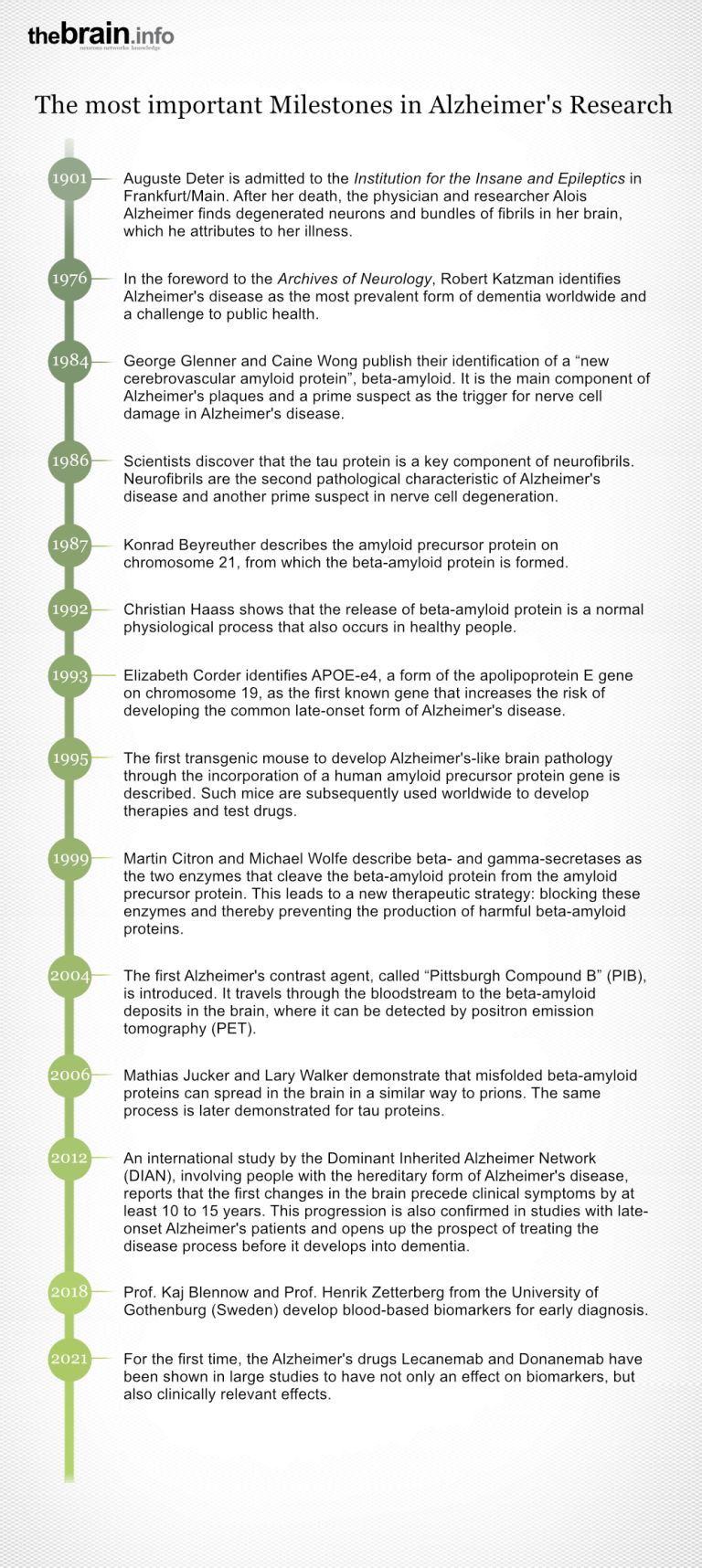

- Alois Alzheimer described the disease in 1907 based on the case of a patient named Auguste Deter in Frankfurt am Main. In 1910, it was mentioned for the first time under the name Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's disease is a neurodegenerative disorder and a form of dementia. In addition to Alzheimer's, there are other types of dementia, such as frontotemporal dementia and vascular dementia.

- Alzheimer's is the most common form of dementia in people over the age of 60, accounting for about 60 percent of all dementia cases.

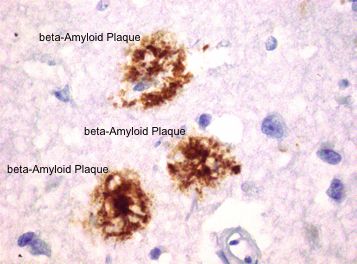

- Alzheimer's is defined by the presence of deposits in the brain: so-called beta-amyloid plaques between the cells and thread-like tau fibrils in the nerve cells.

- Alzheimer's is a multifactorial disease, meaning there are numerous causes and risk factors, including genetic and epigenetic influences, lifestyle, and certain pre-existing conditions.

- The most important proven risk factor is old age.

- Until recently, there was no causal treatment; only the symptoms could be alleviated with medication. Although the latest drugs are effective against amyloid plaques and slow down the progression of the disease, they cannot yet cure it.

Alzheimer's disease

Morbus Alzheimer

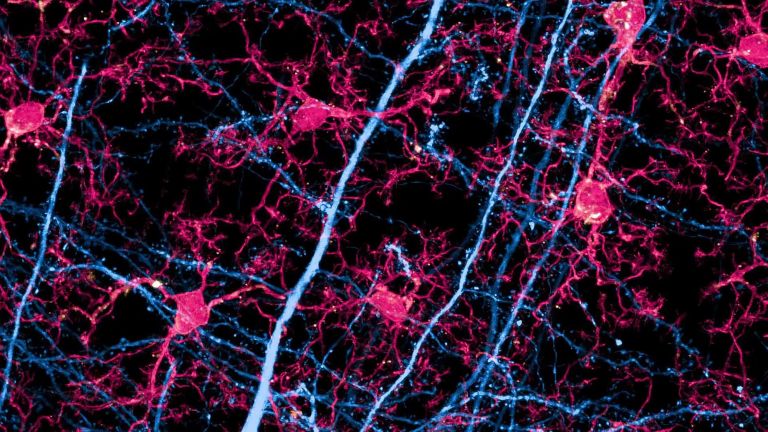

Alzheimer's disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by cortical atrophy, nerve cell loss, synapse loss, and deposits of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, leading to dementia and loss of function. Early symptoms include memory problems, speech disorders, executive deficits, depressive moods, and subtle personality changes. As the disease progresses, global cognitive impairment, aphasia, agnosia, apraxia, and behavioral abnormalities such as apathy, restlessness, and sleep disorders occur. The disease was first described in 1907 by Alois Alzheimer.

- The global cost of Alzheimer's and other dementias was estimated at approximately $1.3 trillion for 2019.

- About three-quarters of the costs are incurred in high-income countries, mainly North America and Western Europe.

- In some high-income countries, between one-third and one-half of people with dementia are placed in costly residential and nursing homes. The annual cost there is $45,500 per patient.

- In low-income countries, only a small proportion of people with dementia live in nursing homes. There, unpaid, informal care is usually provided by relatives and other caregivers. As a result, the average annual cost is “only” $2,575.

- The costs of informal and formal care each account for about 42 percent of Alzheimer's-related costs, while the direct costs of medical therapies are much lower.

- Low-income countries recently accounted for only about 0.25 percent of global costs, while these countries account for 2.5 percent of global cases. Middle-income countries, on the other hand, accounted for about 25 percent of global costs (with 60 percent of cases), while high-income countries accounted for 74 percent of costs and 39 percent of all patients. However, poorer countries are catching up, with strong growth reported particularly in Africa.

- It is estimated that global costs will rise by about 5 percent annually and reach approximately $1.6 trillion in 2050.

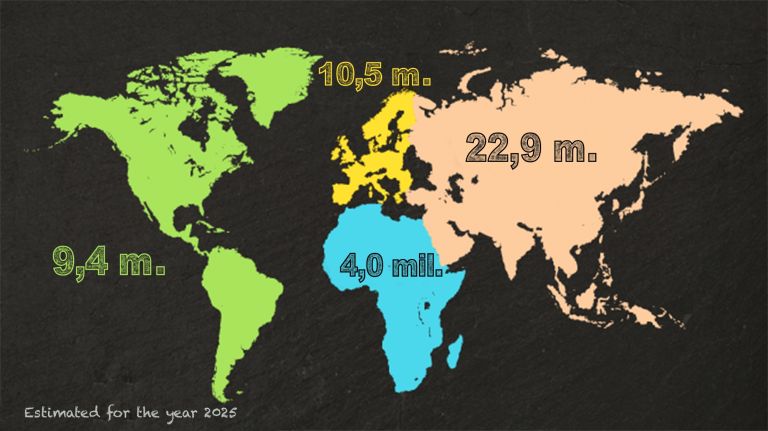

- According to statistics, 35.6 million people suffered from dementia in 2010. It is estimated that 24 million of them had not yet been diagnosed.

- In 2019, the figure was 57 million.

- According to the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019, the number of patients is expected to rise to 152.8 million by 2050. This is mainly due to the growing population and the higher average age of the population. In contrast, the proportion of people with the disease in the various age groups will remain relatively unchanged.

- Broken down by region, the increase in patients will be lowest in the rich countries of the Pacific region (+53%), followed by Western Europe (+74%). In North Africa, the Middle East, and the eastern part of the sub-Saharan countries, however, researchers from the Global Burden of Disease Study expect the number of cases to increase sevenfold (approx. 350% in each case).

The history of Alzheimer's disease began in 1901 with the admission of Auguste Deter to the “Institution for the Insane and Epileptics” in Frankfurt am Main. The patient suffered from forgetfulness and delusions. The transcript of the conversation that the psychiatrist in charge subsequently made wrote scientific history.

It marked the beginning of research into a disease that entered medical history under the name of the psychiatrist: Alois Alzheimer ▸ Alois Alzheimer – Neurologist with a Microscope. The preliminary diagnosis was “presenile insanity.”

Alzheimer's disease

Morbus Alzheimer

Alzheimer's disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by cortical atrophy, nerve cell loss, synapse loss, and deposits of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, leading to dementia and loss of function. Early symptoms include memory problems, speech disorders, executive deficits, depressive moods, and subtle personality changes. As the disease progresses, global cognitive impairment, aphasia, agnosia, apraxia, and behavioral abnormalities such as apathy, restlessness, and sleep disorders occur. The disease was first described in 1907 by Alois Alzheimer.

Different types of dementia and their causes

The term dementia describes a syndrome, a combination of several signs of illness (symptoms). These include cognitive deficits, deficits in word finding, and later in orientation and everyday skills. The causes of these symptoms remained unknown during Auguste Deter's lifetime; only their effects could be recorded. The dementia later named after Alzheimer initially manifests as short-term memory impairment. Over time, long-term memory also disappears, causing those affected to lose more and more abilities and skills until they are no longer able to cope with everyday life.

Today, we know that there are several types of dementia and that there are many possible causes. Alzheimer's dementia, along with frontotemporal dementia, Lewy body dementia, and Parkinson's dementia, is one of the neurodegenerative diseases in which nerve cells are destroyed. However, vascular (blood vessel-related) dementias are also common. In addition, there are secondary forms of dementia that can be the result of multiple sclerosis or a metabolic disorder, for example.

1903–1910: Organic causes?

When Alzheimer moved to Munich in 1903, there was still no classification of mental disorders. Furthermore, the organic causes of mental illness were still far from being generally accepted. From 1903 to 1906, Auguste Deter remained in the Frankfurt institution, but Alzheimer monitored her condition, which was deteriorating, from afar. She died in 1906, “completely demented,” as Alzheimer noted.

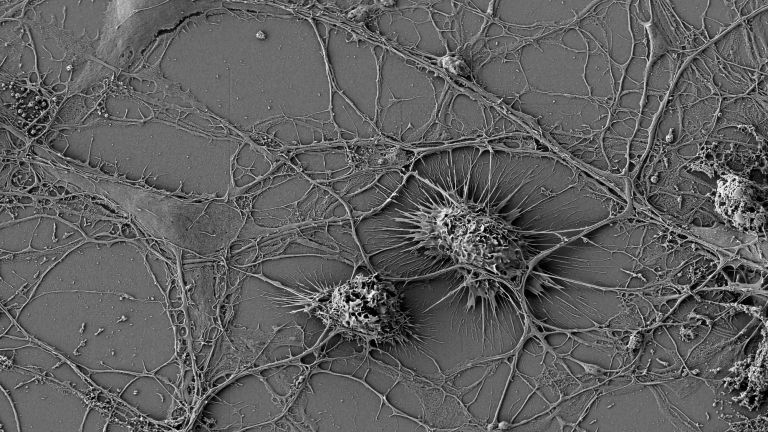

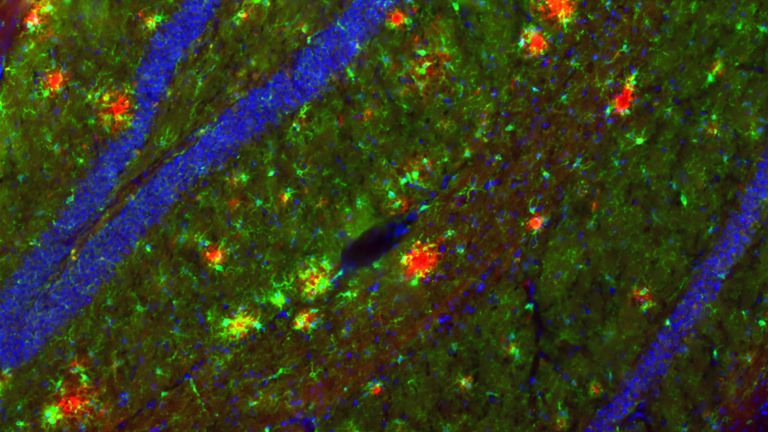

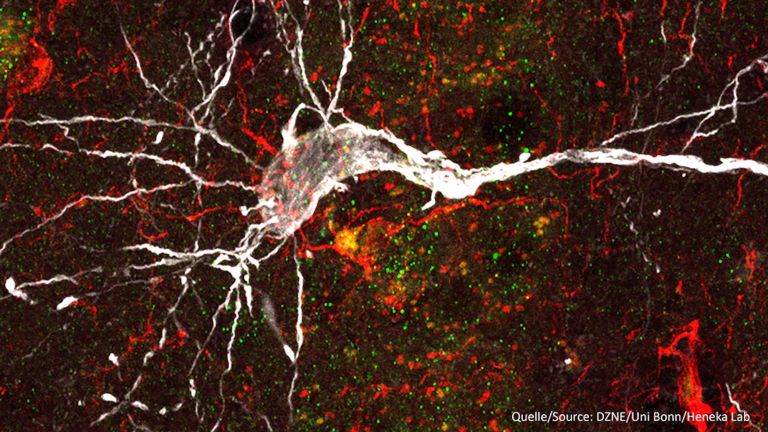

When he examined Deter's brain under a microscope, he found destroyed nerve cells with bundles of fibrous structures – neurofibrils – as well as deposits outside the cells, known as senile plaques. For Alzheimer, this confirmed his theory that mental illnesses must have organic causes. In 1907, he published a treatise “on a peculiar disease of the cerebral cortex,” but it was not until later that the opinion prevailed that Deter had suffered from a new type of disease. In 1910, the Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie (Textbook of Psychiatry) listed this form for the first time under the name “Alzheimer's disease.”

The 1970s and 1980s: First initiatives, first controversy

Until the early 1970s, the mechanisms remained unclear, but it became apparent that Alzheimer's disease increases with age. It is by no means a rare disease affecting younger patients, as Alois Alzheimer himself had believed. Fears arose that demographic change – more and more older people and fewer and fewer young people – could lead to an explosion in patient numbers. This prompted the US to establish the National Institute on Aging (NIA) in 1974. In 1976, Robert Katzman († 2008), a pioneer in Alzheimer's research, identified Alzheimer's disease as the most common form of dementia, accounting for 60 percent of all cases. In 1980, the world's first Alzheimer's society, the Alzheimer's Association, was founded in the USA. Four years later, funding began for a network of Alzheimer's centers.

In 1984, George Glenner († 1995) and Caine Wong from the University of California in San Diego published findings showing that a peptide called beta-amyloid is the main component of the plaques – the first prime suspect for triggering nerve cell damage. Three years later, Konrad Beyreuther, Benno Müller-Hill († 2018) and their colleagues at the University of Cologne showed that the beta-amyloid peptide is formed by cleavage from a large precursor protein, the amyloid precursor protein (APP).

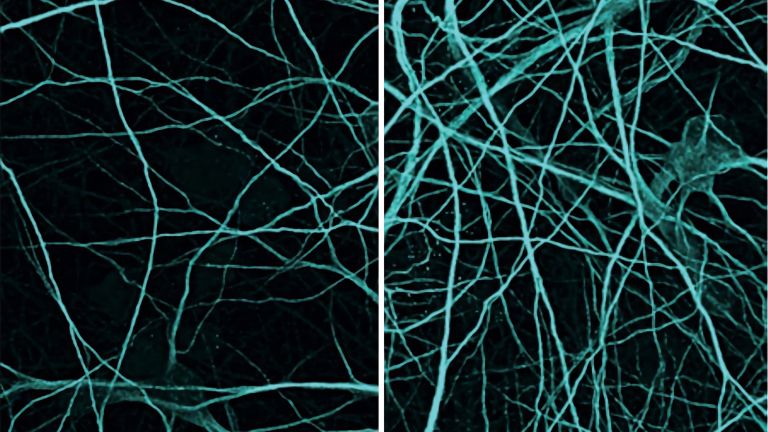

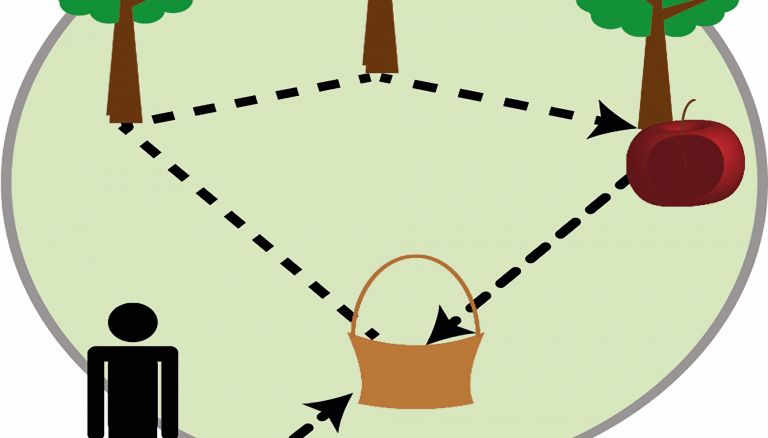

The role that APP plays in a healthy body is still not fully understood. One of its best-documented functions is its involvement in the formation, maintenance, and repair of synapses, the contact points between nerve cells. It also appears to protect neurons from harmful influences.

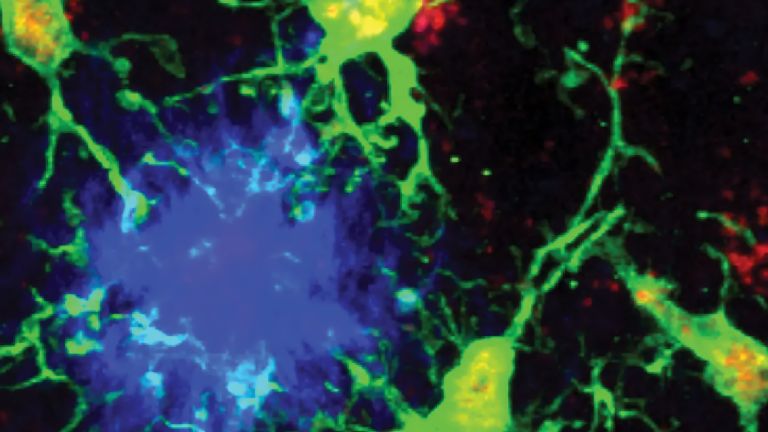

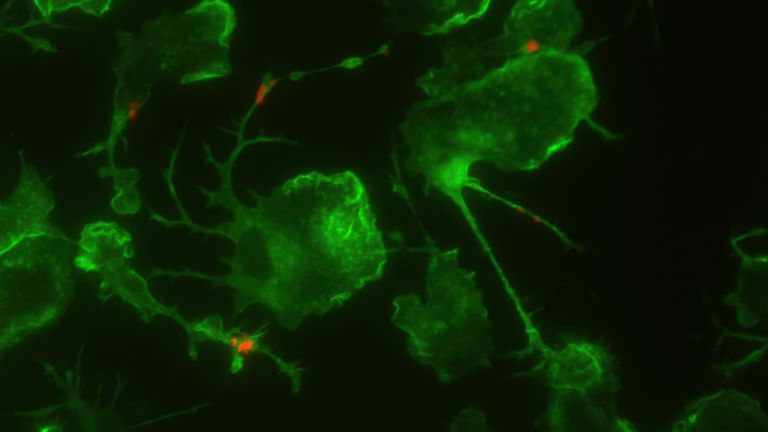

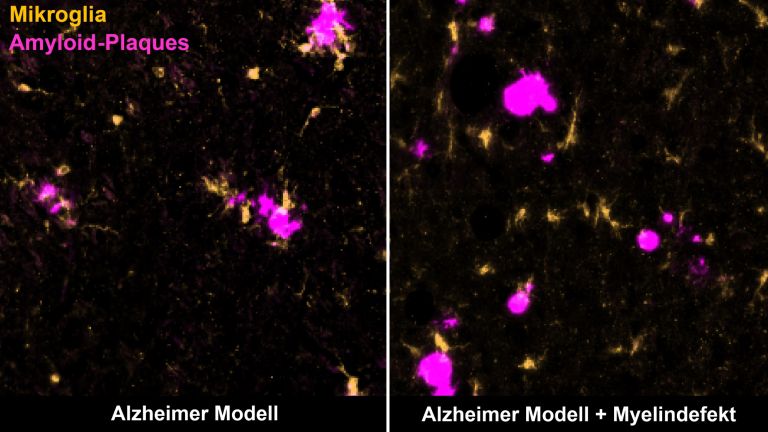

If APP is cleaved enzymatically in a certain way, beta-amyloid peptide may be released. This can clump together to form plaques. It is believed that an intermediate product in the formation of the plaques, known as oligomers, damages neighboring nerve cells and, above all, synapses. The “beta-amyloid hypothesis” has gained more and more supporters over the years. They are called “Baptists” in the research community.

In 1986, Inge Grundke-Iqbal († 2012) and colleagues from the New York State Office for People with Developmental Disabilities (OPWDD) published a very interesting paper. According to their findings, a protein called “tau,” which is associated with certain cytoskeletal proteins called microtubules, is a component of neurofibrils, the thread-like structures within cells. Tau appears to be the second main suspect. The “tau hypothesis” is supported by the “tauists.” According to Eckhard and Eva-Maria Mandelkow from the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases in Bonn, tau plays an important role in healthy bodies: “It stabilizes the microtubules, which are particularly important for transport processes in nerve cells. In Alzheimer's disease, tau falls off the microtubules, clumps together to form neurofibrils, and the microtubules become unstable.”

Alzheimer's disease

Morbus Alzheimer

Alzheimer's disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by cortical atrophy, nerve cell loss, synapse loss, and deposits of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, leading to dementia and loss of function. Early symptoms include memory problems, speech disorders, executive deficits, depressive moods, and subtle personality changes. As the disease progresses, global cognitive impairment, aphasia, agnosia, apraxia, and behavioral abnormalities such as apathy, restlessness, and sleep disorders occur. The disease was first described in 1907 by Alois Alzheimer.

Other causes come into play

The joint occurrence of plaques and neurofibrils is characteristic of Alzheimer's disease The debate over which of the two events is the cause has shaped research for years. The current consensus is that the plaques form first, but that the cognitive deficits in Alzheimer's are closely related to the amount and distribution of tau fibrils.

It is still unclear what causes these initially harmless proteins to become pathological. We all produce amyloid from the very beginning, even as babies in the womb. Production alone does not lead to Alzheimer's pathology – it is a normal process. However, the chance of beta-amyloid clumping together and forming plaques probably increases with age.

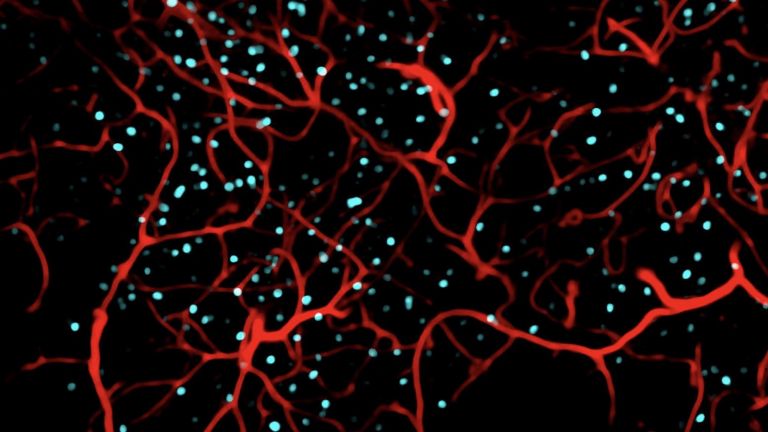

But according to Eckhard Mandelkow, Alzheimer's dementia is “not a disease based solely on tau or beta-amyloid.” There are many other possible reasons that “have something to do with it.” “Alzheimer's dementia is a multifactorial disease. Population studies have shown that there are several factors that increase the risk of Alzheimer's disease. Examples include high blood pressure and obesity.” These lead to vascular damage and, as a result, reduced blood flow to the brain. This impairs the energy supply to the nerve cells. Mandelkow: “That's why recommending a healthy lifestyle is actually the best thing you can do.”

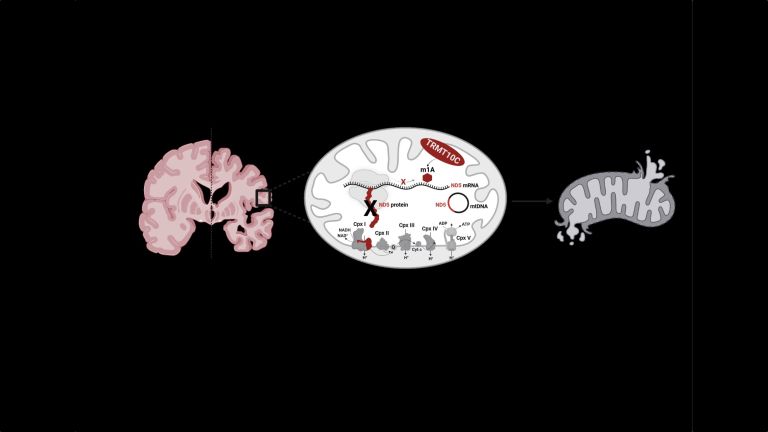

Inflammatory processes are also involved in the development of Alzheimer's, as are disorders of the mitochondria, the “power plants” of the cells. In addition to these factors, genetic risk factors and certain epigenetic influences have also been identified. However, changes in individual genes that lead to the so-called familial form of Alzheimer's dementia are responsible for less than one percent of patients.

One thing is certain today. Eckhard Mandelkow puts it this way: “Aging is the most important risk factor. But the risk can be reduced: what is good for the heart is also good for the brain.”

Alzheimer's disease

Morbus Alzheimer

Alzheimer's disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by cortical atrophy, nerve cell loss, synapse loss, and deposits of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, leading to dementia and loss of function. Early symptoms include memory problems, speech disorders, executive deficits, depressive moods, and subtle personality changes. As the disease progresses, global cognitive impairment, aphasia, agnosia, apraxia, and behavioral abnormalities such as apathy, restlessness, and sleep disorders occur. The disease was first described in 1907 by Alois Alzheimer.

Research gains momentum in the 1990s

In 1987, hope for improvement arises. The first test of a drug for Alzheimer's symptoms begins in the USA: Tacrin is based on the modulation of a neurotransmitter (acetylcholine) and its receptors. It compensates for the lack of acetylcholine that occurs in Alzheimer's disease due to the death of cholinergic neurons. However, its effectiveness is low, and tacrine, which was approved in 1993, has since been withdrawn from the market in many countries due to its side effects. Also in 1993, Allen Roses († 2016) and colleagues at Duke University in North Carolina published an important paper: they demonstrated that APOE-e4, a form of the apolipoprotein E gene on chromosome 19, increases the risk of developing Alzheimer's dementia.

The following year, the disease took on a new face when Ronald Reagan announced his diagnosis to the public.

As early as 1980, associations were formed in Canada and the US to support Alzheimer's research and patients. In Germany, the first private association, the Alzheimer Forschung Initiative e.V., was founded in 1995, followed in 2000 by the Hans und Ilse Breuer-Stiftung. Finally, in 2009, Alzheimer's Disease International (ADI), the umbrella organization for Alzheimer's societies worldwide, published the first World Alzheimer Report. It paints a bleak picture.

Alzheimer's disease

Morbus Alzheimer

Alzheimer's disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by cortical atrophy, nerve cell loss, synapse loss, and deposits of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, leading to dementia and loss of function. Early symptoms include memory problems, speech disorders, executive deficits, depressive moods, and subtle personality changes. As the disease progresses, global cognitive impairment, aphasia, agnosia, apraxia, and behavioral abnormalities such as apathy, restlessness, and sleep disorders occur. The disease was first described in 1907 by Alois Alzheimer.

Recommended articles

Dementia: increasing social and economic relevance

While the number of dementia patients was estimated at 35.6 million in 2010, it had already risen to 57 million by 2019, and the latest projections indicate that it is expected to increase to 152.8 million by 2050. The increase is not only due to demographic change, but also to increased awareness: this increases the likelihood of an Alzheimer's diagnosis, as it creates the conditions for access to treatment and care.

With better detection and care for patients, costs are also rising: in 2019, the cost of all types of dementia was estimated at approximately $1.3 trillion. And so, after 106 years, Alzheimer's disease has gone from being a marginal phenomenon to a problem that has reached the center of society. Society is now beginning to grapple with the implications.

Alzheimer's disease

Morbus Alzheimer

Alzheimer's disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by cortical atrophy, nerve cell loss, synapse loss, and deposits of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, leading to dementia and loss of function. Early symptoms include memory problems, speech disorders, executive deficits, depressive moods, and subtle personality changes. As the disease progresses, global cognitive impairment, aphasia, agnosia, apraxia, and behavioral abnormalities such as apathy, restlessness, and sleep disorders occur. The disease was first described in 1907 by Alois Alzheimer.

The therapy of the future: as multifactorial as the disease itself

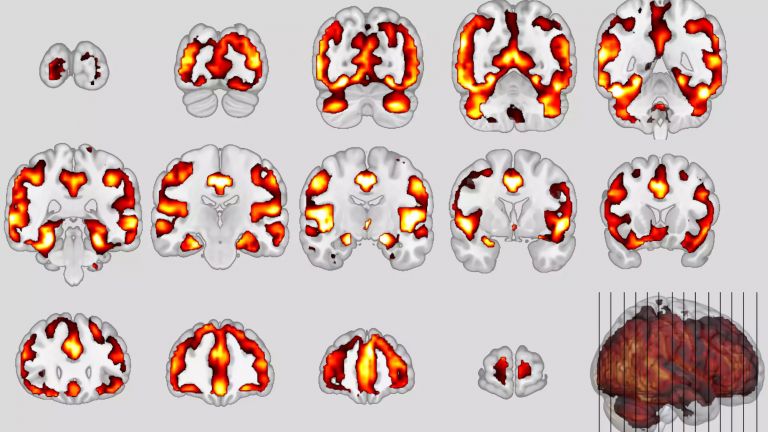

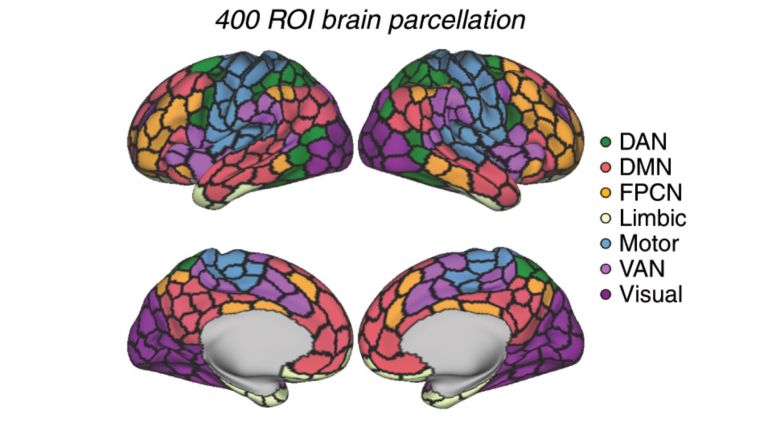

Diagnostic capabilities have improved enormously over the years. Imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging make even the smallest changes in the brain visible. And with a special variant of positron emission tomography, radiologists can even visualize deposited amyloid and quantify its amount.

Biomarkers in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) also provide clues about the disease process. Particularly informative is the ratio of two amyloid components, the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio, as well as the concentration of tau and its phosphorylated variant (p-tau). While these samples still have to be obtained by lumbar puncture, in which fluid is extracted from the lumbar spine using a thin needle, a simpler procedure could soon become established: a blood test already approved in the USA also measures p-Tau and the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio.

However, the greatest progress in recent years has been made with antibodies that target amyloid and can slow the progression of the disease. Donanemab and lecanemab are the first causal therapies to become available – with the caveat that these drugs are likely to benefit only a small proportion of patients for the time being. The reason for this, in addition to the high price of around €20,000 per year, is the numerous advanced imaging examinations that are necessary to detect any side effects at an early stage.

Therefore, referring to the possibilities of prevention remains the best advice at present. According to Hans Förstl, former director of the Clinic and Polyclinic for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy at the Klinikum rechts der Isar, good prevention includes the following: “It is very important to stimulate the brain. Not with mindless brain training, but with everything that brings people joy.” What is often neglected, he says, is the treatment of comorbidities that additionally impair mental performance.

Much has improved in the meantime. While the first drugs could only slightly delay the progression of the disease, their successors act directly against the amyloid deposits. They can significantly reduce existing deposits and slow down the formation of new ones. Over a period of 18 months, mental decline and the loss of everyday functions are slowed down by a quarter to a third. And there is hope that starting therapy even earlier will significantly delay the onset of severe symptoms.

Further reading

- Alzheimer’s[MS2] Association (USA): Very comprehensive and layman-friendly texts, infographics, videos, interactive tools. Good mix of basic knowledge, diagnostics, therapy, care, prevention. Many printable PDF fact sheets; to the website.

- Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI): Publisher of the World Alzheimer Reports; to the website.

- Mayo Clinic – Alzheimer’s Disease Center: Clear, medically reviewed articles. Well structured according to symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment. Very clear symptom and progression tables; to the website.

First published on September 18, 2013

Last updated on October 20, 2025