The Epithalamus

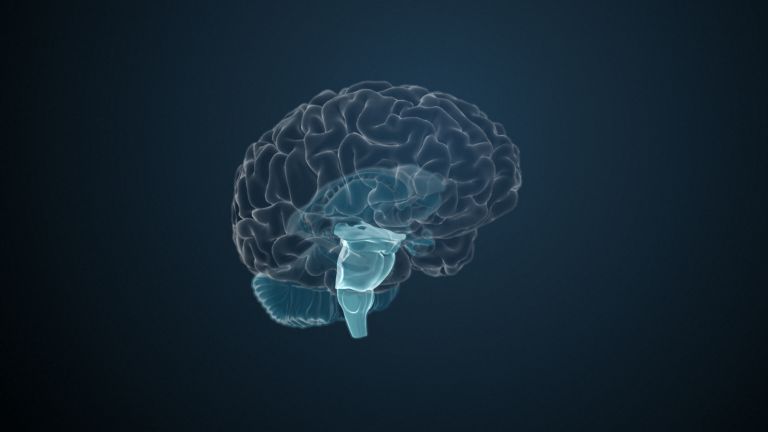

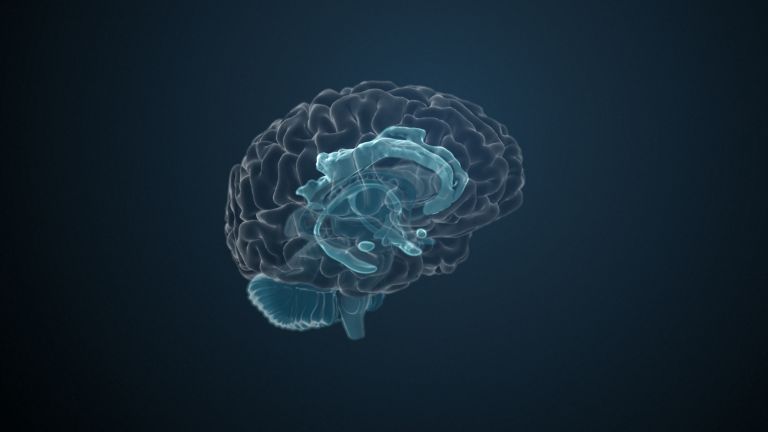

The epithalamus, together with the pineal gland, has long captured the imagination of philosophers. Even today, this part of the diencephalon remains a mystery to neuroscientists. It consists mainly of two reins and a cone.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Jochen F. Staiger

Published: 09.10.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

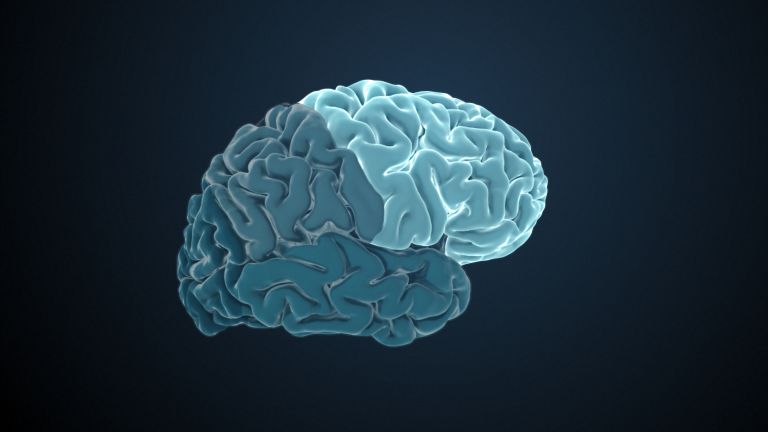

In classical anatomy, the Epithalamus comprises two structures – firstly, the epiphysis, or pineal gland, which influences the sleep-wake cycle via its Hormone Melatonin. And secondly, the habenulae, which play an important role in avoidance, reward, stress, pain, and even decision-making and addiction. However, the two structures have nothing to do with each other in mammals; the ancient anatomists simply did not have the means to make this discovery.

Epithalamus

epithalamus

A part of the diencephalon (midbrain) located behind the thalamus (the largest part of the midbrain). It includes the habenulae and the epiphysis, among other structures.

Hormone

Hormones are chemical messengers in the body. They serve to transmit information between organs and cells, usually slowly, e.g., to regulate blood sugar levels. Many hormones are produced in glandular cells and released into the blood. At their destination, e.g., an organ, they dock at binding sites and trigger processes inside the cell. Hormones have a broader effect than neurotransmitters; they can influence various functions in many cells of the body.

Melatonin

Melatonin is a hormone released by the pineal gland in the brain when it is dark. Melatonin levels are highest at night and then decrease throughout the day. This makes it an important messenger substance for the "internal clock" and it appears to play a particularly important role in regulating sleep.

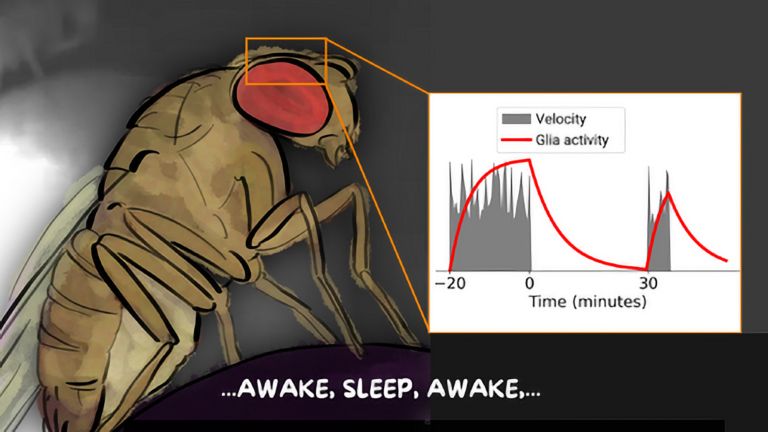

The Hormone Melatonin from the pineal gland controls the sleep-wake cycle: It binds to receptors in the Suprachiasmatic nucleus in the Hypothalamus – essentially the human body's internal clock – and stimulates sleep. The pineal gland only produces melatonin in darkness, i.e. at night, and acts as a kind of timer in the body. It is said that older people release less melatonin and therefore need less sleep. The hormone also plays a role in the development of jet lag during long-distance travel and in physical problems caused by shift work.

Melatonin also influences the gonads by preventing the pituitary gland from releasing gonadotropic hormones, i.e., hormones that stimulate the gonads, including follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone. If the pineal gland fails in children, this can lead to early puberty. Just as an aside: in amphibians, melatonin leads to depigmentation of the skin.

Medications containing melatonin are said to combat jet lag, promote sleep, or scavenge free radicals and thus prevent cancer. However, many of these effects have not been proven. In 2010, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) found that the claim “melatonin contributes to the alleviation of the subjective feeling of jet lag” was scientifically justified, but that there was insufficient evidence that taking melatonin-containing products improves sleep quality or shortens the time it takes to fall asleep.

Hormone

Hormones are chemical messengers in the body. They serve to transmit information between organs and cells, usually slowly, e.g., to regulate blood sugar levels. Many hormones are produced in glandular cells and released into the blood. At their destination, e.g., an organ, they dock at binding sites and trigger processes inside the cell. Hormones have a broader effect than neurotransmitters; they can influence various functions in many cells of the body.

Melatonin

Melatonin is a hormone released by the pineal gland in the brain when it is dark. Melatonin levels are highest at night and then decrease throughout the day. This makes it an important messenger substance for the "internal clock" and it appears to play a particularly important role in regulating sleep.

Suprachiasmatic nucleus

nucleus suprachiasmaticus

A nucleus of the hypothalamus that plays a central role in circadian rhythms, including the sleep-wake cycle. It is the master clock, the body's most important internal clock, controlling melatonin production in the epiphysis. It receives direct input from the retinal ganglion cells.

Hypothalamus

The hypothalamus is considered the center of the autonomic nervous system, meaning it controls many motivational states and regulates vegetative aspects such as hunger, thirst, and sexual behavior. As an endocrine gland (which, unlike an exocrine gland, releases its hormones directly into the blood without a duct), it produces numerous hormones, some of which inhibit or stimulate the pituitary gland to release hormones into the blood.In this function, it also plays an important role in the response to pain and is involved in pain modulation.

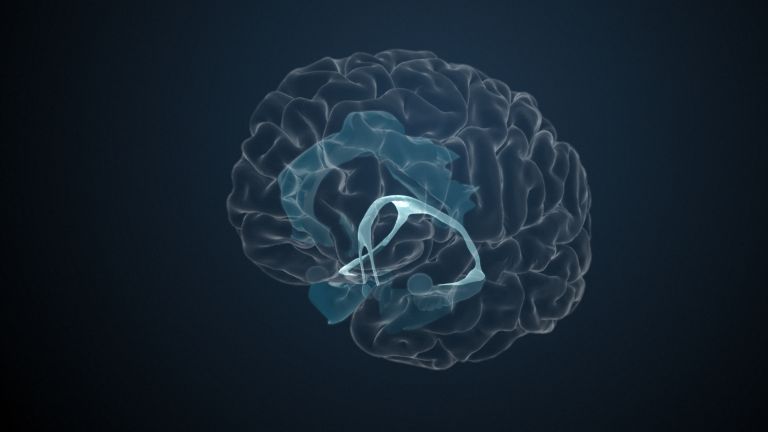

“The habenular nuclei probably form a switching station between the olfactory brain and the brain stem” – this is what older textbooks say. But these may need to be rewritten, as recent findings suggest that the habenular nuclei do not receive any olfactory information at all.

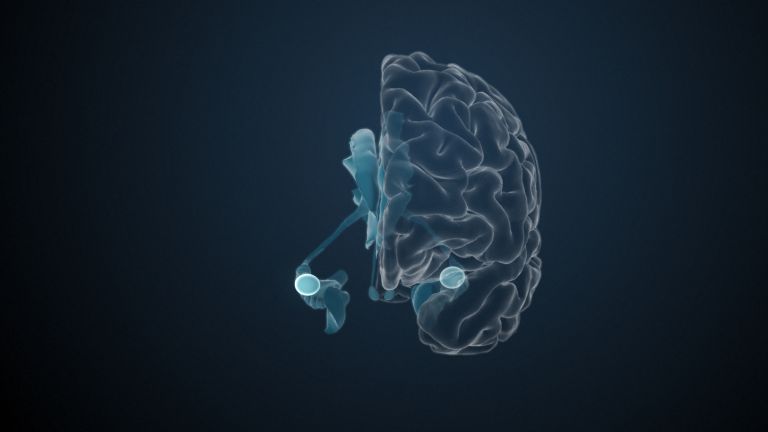

Instead, other – and more far-reaching – tasks are emerging for the habenula: information about mistakes and punishment is transmitted from the Basal ganglia to the habenula, which then influences structures of the dopaminergic system with the Ventral tegmental area and the Substantia nigra – and this function also inhibits motor activity. Information about pain and stress from the Limbic system leads to the same result, whereby the habenula then influences not only the dopaminergic nuclei but also the Raphe nuclei and thus Serotonin production.

Basal ganglia

Nuclei basales

The basal ganglia are a group of subcortical nuclei (located beneath the cerebral cortex) in the telencephalon. The basal ganglia include the globus pallidus and the striatum, and, depending on the author, other structures such as the substantia nigra and the subthalamic nucleus. The basal ganglia are primarily associated with voluntary motor function, but they also influence motivation, learning, and emotion.

ventral

A positional term – ventral means "towards the abdomen." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction perpendicular to the neural axis, i.e., downwards or forwards.

In animals (that do not walk upright), the term is simpler, as it always means toward the abdomen. Due to the upright posture of humans, the brain bends in relation to the spinal cord, making ventral mean "forward."

Ventral tegmental area

Ventral tegmental area/Area tegmentalis ventralis7ventral tegmental area

Located in the midbrain, the uppermost section of the brain stem, is the ventral tegmental area (VTA) – a central component of the reward system. The area itself is not particularly large, but its influence is immense: the neurons of the VTA send their axons to the nucleus accumbens and widely into the prefrontal cortex (PFC), where they release the neuromodulator dopamine. In this way, they enhance learning processes, but can also contribute to the development of addictions.

Substantia nigra

A nucleus complex in the ventral mesencephalon that plays a central role in initiating and modulating movement. It appears dark due to neuromelanin. Its dopaminergic neurons project via the nigrostriatal pathways to the putamen and caudate nucleus. Failure of these neurons leads to the typical symptoms of Parkinson's disease.

Limbic system

The limbic system is a functional unit in the brain. It consists of interconnected structures, primarily in the cerebrum and diencephalon. The structures assigned to the system vary depending on the source, but the most important components are the hippocampus, amygdala, cingulate gyrus, septum, and mammillary bodies. The limbic system is involved in autonomic and visceral processes as well as in mechanisms of emotion, memory, and learning. Some authors mistakenly reduce the limbic system to the emotional world by referring to it as the "emotional brain."

Raphe nuclei

The raphe nuclei are located in the reticular system and are distributed throughout the brain stem. They belong to the ascending reticular activating system (ARAS) and are the site of serotonin production.

Serotonin

A neurotransmitter that acts as a messenger in the transmission of information between neurons at their synapses. It is primarily produced in the raphe nuclei of the brain stem and plays a key role in sleep and alertness, as well as emotional well-being.

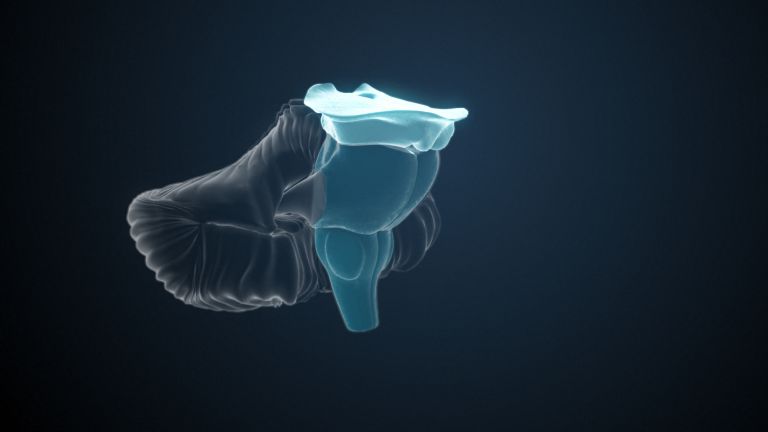

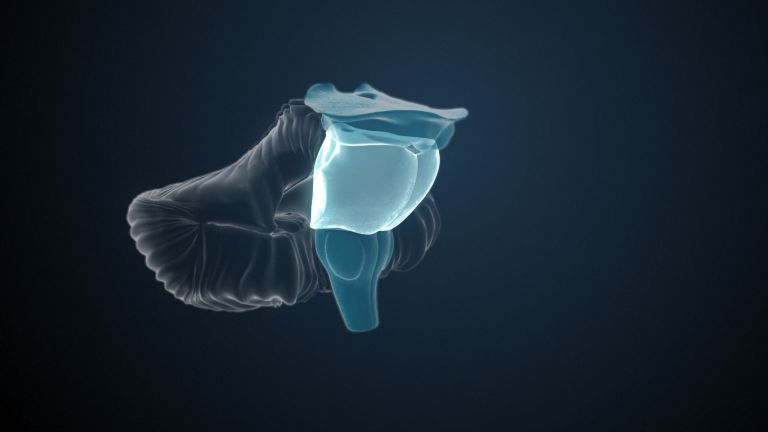

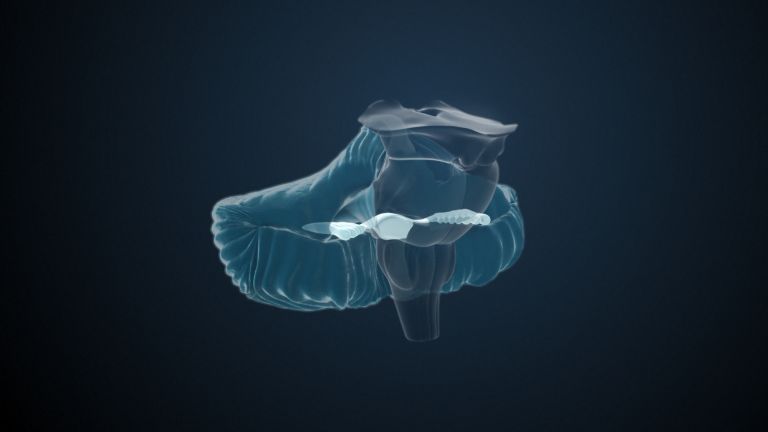

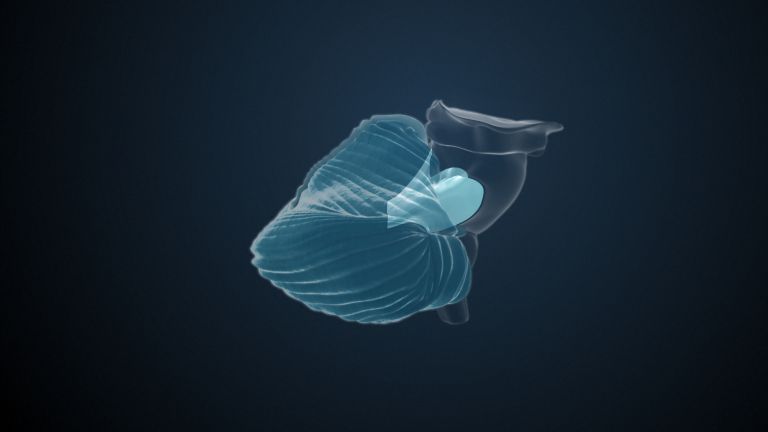

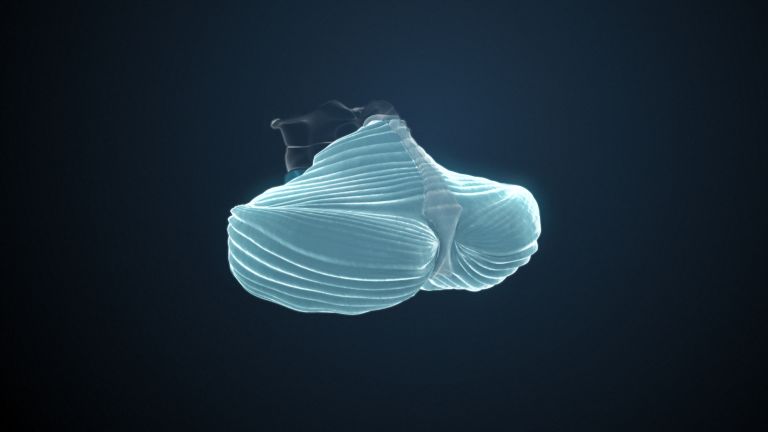

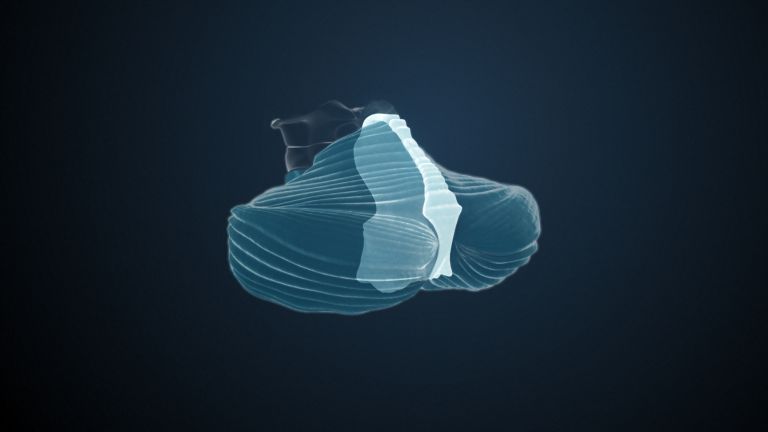

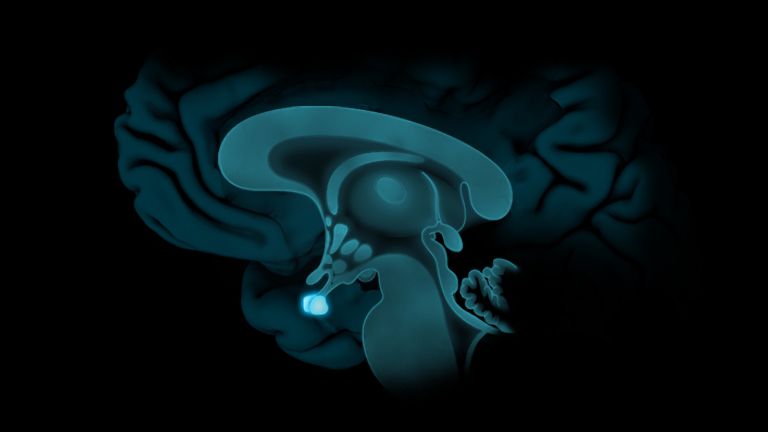

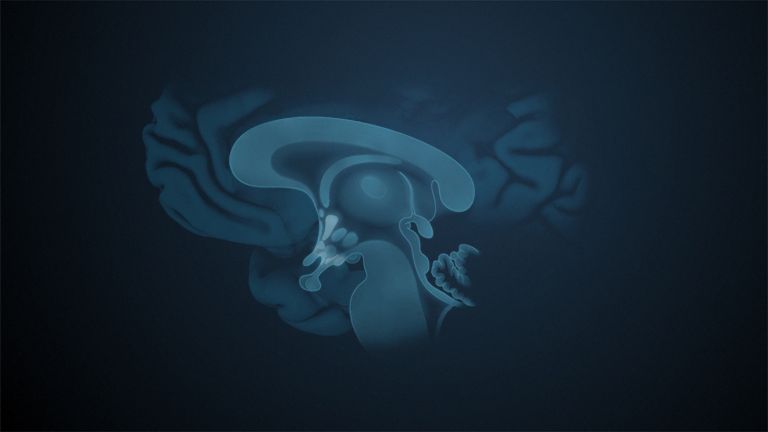

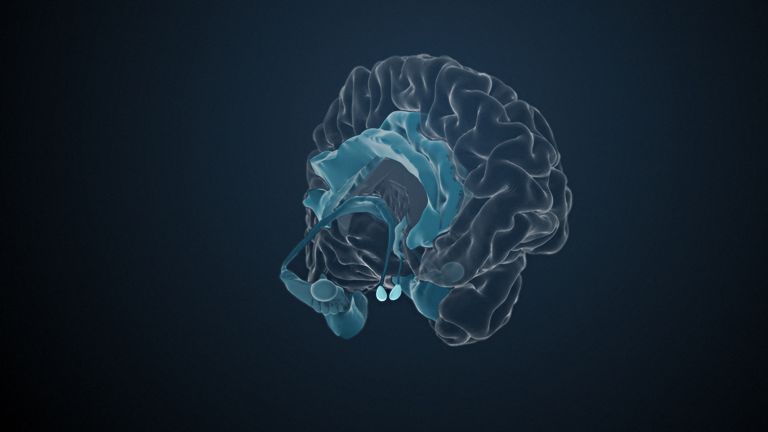

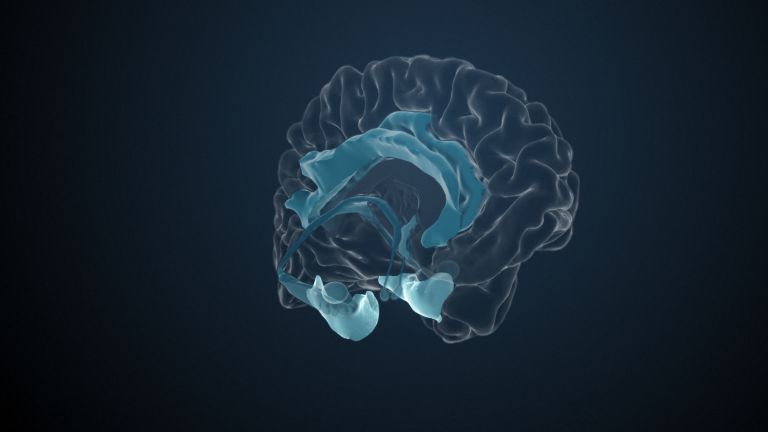

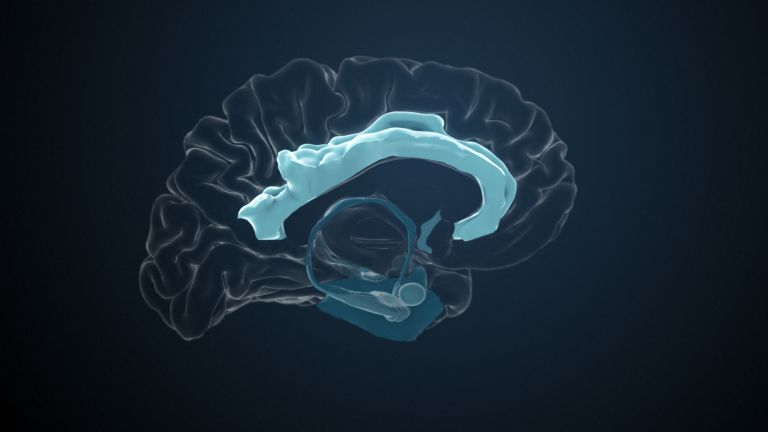

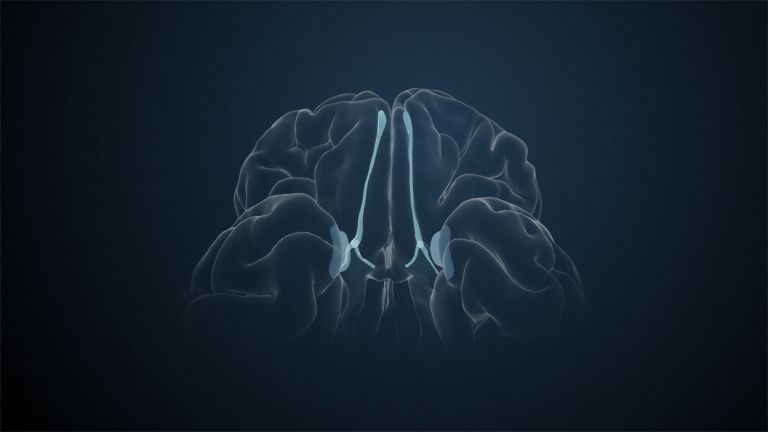

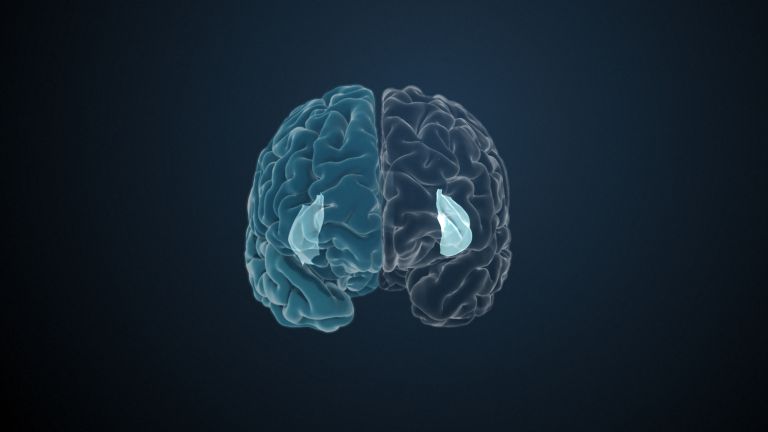

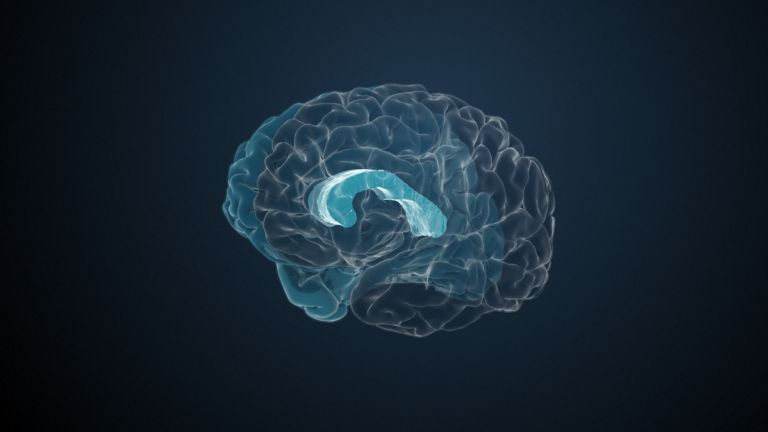

Almost hidden on the rear wall of the third ventricle is the Epithalamus. It sits behind and above the much larger thalamus, which explains its name: The Greek prefix “epi” means “on.” The epithalamus includes the impressive Habenulae – in English, the “reins” – two strands of brain tissue that unite dynamically in the middle, at the unpaired epiphysis, the pineal gland. Viewed from behind, the structure actually resembles the reins of a horse's harness, which are attached to both sides of a bridle.

Three other structures are also considered part of the epithalamus. First, the habenulae continue into the striae medullares, white medullary stripes that run across the thalamus and connect it to the habenulae. Furthermore, the posterior commissure, also known as the epithalamic commissure, and the pretectal area are also considered part of the epithalamus. Commissural fibers always cross from one Hemisphere of the brain to the other, and in the case of the posterior commissure, fibers from the Tectum and the Tegmentum in the midbrain, among others, cross sides. In terms of function, however, both the posterior Commissure and the pretectal area belong to the Visual system the pretectal area is at work in the pupillary reflex, for example, when the pupils dilate in the dark or constrict in sudden light.

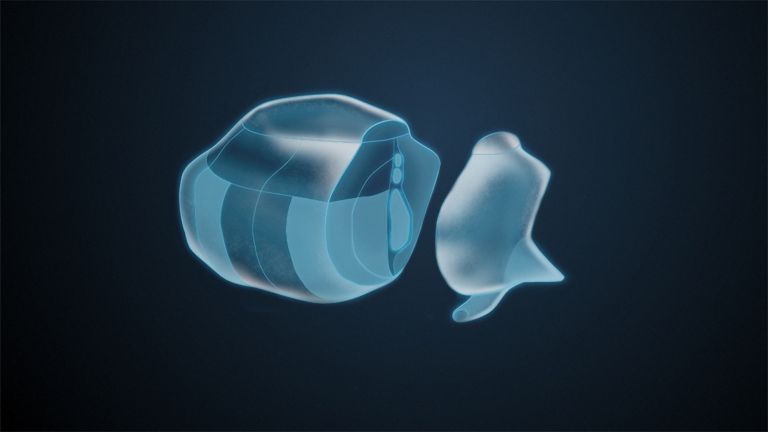

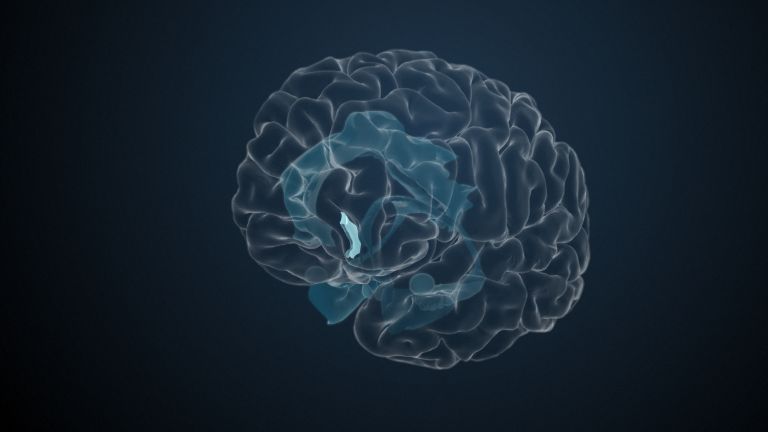

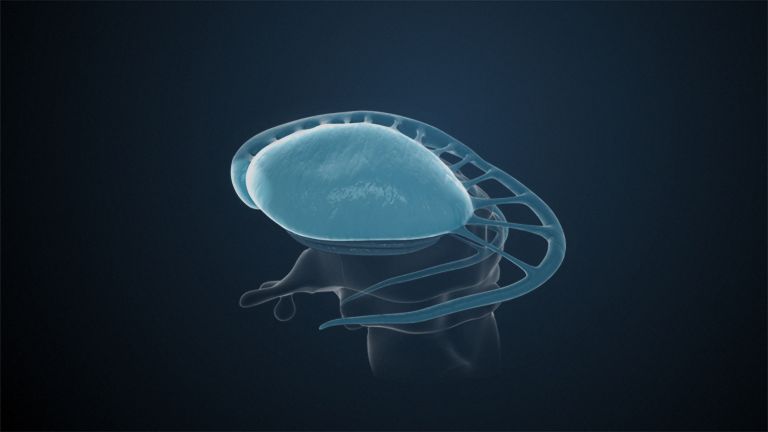

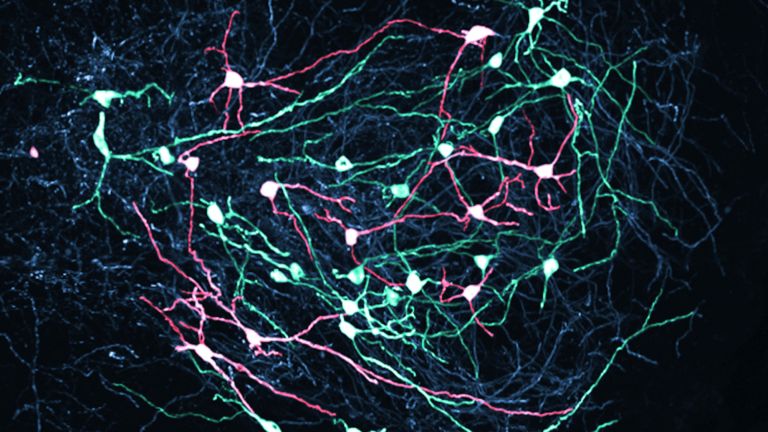

The official star of the epithalamus is probably the epiphysis, the pineal gland. At least by name, it was already known before the birth of Christ; at that time and later, all kinds of theories surrounded this organ, which is less than a centimeter in size: for example, it was assumed that the pineal gland was a kind of valve for thoughts and memories. The gland is located above the tectum, protruding from the third ventricle and shaped like a pine cone. This is where its Latin name comes from: Glandula pinealis, pineal gland. The Epiphysis is largely covered by the inner meninges, which supply blood vessels to the gland. It is mainly composed of pinealocytes, the hormone-producing cells of the glandular tissue. Connective tissue segments the tissue into many vesicles, which look like honeycombs under the microscope when viewed in cross-section. The pineal gland also contains Glial cells as support cells and nerve fibers.

Epithalamus

epithalamus

A part of the diencephalon (midbrain) located behind the thalamus (the largest part of the midbrain). It includes the habenulae and the epiphysis, among other structures.

Habenulae

The habenulae – literally translated as "the reins" – are part of the epithalamus (which is part of the diencephalon) and are primarily involved in the modulation of monoamine neurotransmitters (dopamine, serotonin).

posterior

A positional term – posterior means "towards the back, located at the rear." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction towards the tail.

Hemisphere

The cerebrum and cerebellum each consist of two halves – the right and left hemispheres. In the cerebrum, they are connected by three pathways (commissures). The largest commissure is the corpus callosum.

Tectum

A structure in the midbrain consisting of two pairs of mounds, the upper colliculi and the lower colliculi.

Tegmentum

Tegmentum (from the Latin "tegere," meaning "to cover"). This is the ventral part of the midbrain located beneath the aqueduct. It contains nuclei such as the substantia nigra, the reticular formation, the cranial nerve nuclei, and the red nucleus.

Commissure

A commissure is a fiber connection between two anatomical areas, primarily from one hemisphere to the other. The largest commissure in the human brain is the corpus callosum.

Visual system

The visual system is the part of the nervous system that processes visual information. It primarily comprises the eye, the optic nerve, the optic chiasm, the optic tract, the lateral geniculate nucleus, the optic radiation, the primary visual cortex, and the visual association cortices.

Epiphysis

glandula pinalis/pineal gland

The epiphysis (pineal gland) is an unpaired component of the epithalamus (part of the diencephalon). It is a gland that secretes melatonin. Among other things, the epiphysis controls the "internal clock."

Glial cells

Glia cells are the second largest group of cells in the brain after neurons. For a long time, they were considered inactive elements of the brain, referred to as "nerve cement." Today, we know that the different types of glia cells (astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia in the CNS; Schwann cells in the PNS) perform clearly defined tasks in the nervous system. For example, they respond to pathogens, play an important role in nourishing nerve cells, and insulate nerve fibers. They account for slightly more than 50 percent of the brain's cells, compared to neurons.

Function of the epiphysis

“There is a small gland in the brain in which the soul performs its function more specifically than in any other part of the body,” wrote the philosopher René Descartes about the pineal gland in the 17th century. He believed that body and soul unite in this organ – an idea that is completely divorced from reality. Today we know that the pineal gland produces the Hormone Melatonin (see box) and releases it into the blood. However, it only does this at night. Daylight inhibits the enzymes that produce melatonin from Serotonin in two steps.

Originally, the pineal gland was not only an endocrine organ, but also a sensory organ with photoreceptor cells. However, these have regressed in the course of evolution. In fact, some amphibians and reptiles, such as the New Zealand tuatara (often referred to as a living fossil), have a third Eye under the skin of their skull, the parietal eye. This allows light to fall directly into the brain, enabling the animals to perceive light-dark differences particularly well. In mammals, however, the skull is so thick that the pineal gland no longer needs its photoreceptor cells. Nevertheless, it receives light signals via extensive nerve pathways that run from the Retina to the Hypothalamus and into the spinal cord, reaching the Epiphysis via the superior cervical ganglion, the cervical sympathetic nerve. These are also the only nerve fiber connections to the organ in mammals.

The pineal gland participates in the regulation of the day and night rhythm via melatonin and, in addition to a variety of other internal organs, also influences the gonads. In addition to melatonin, the epiphysis also releases other compounds, neuropeptides, into the blood, the effects of which are still unknown. Even the function of melatonin is still being researched. The pineal gland therefore remains an exciting field of research for neuroscientists today.

Even before the age of 20, i.e. at a relatively young age, the epiphysis begins to calcify. Support cells multiply rapidly, actual glandular tissue dies off, and cysts form in which calcium and magnesium salts are deposited. Doctors call this phenomenon “brain sand” or “acervulus” – these calcium deposits are clearly visible on X-rays. However, their significance is still unclear.

Hormone

Hormones are chemical messengers in the body. They serve to transmit information between organs and cells, usually slowly, e.g., to regulate blood sugar levels. Many hormones are produced in glandular cells and released into the blood. At their destination, e.g., an organ, they dock at binding sites and trigger processes inside the cell. Hormones have a broader effect than neurotransmitters; they can influence various functions in many cells of the body.

Melatonin

Melatonin is a hormone released by the pineal gland in the brain when it is dark. Melatonin levels are highest at night and then decrease throughout the day. This makes it an important messenger substance for the "internal clock" and it appears to play a particularly important role in regulating sleep.

Serotonin

A neurotransmitter that acts as a messenger in the transmission of information between neurons at their synapses. It is primarily produced in the raphe nuclei of the brain stem and plays a key role in sleep and alertness, as well as emotional well-being.

Eye

bulbus oculi

The eye is the sensory organ responsible for perceiving light stimuli – electromagnetic radiation within a specific frequency range. The light visible to humans lies in the range between 380 and 780 nanometers.

Retina

The retina is the inner layer of the eye covered with pigment epithelium. The retina is characterized by an inverse (reversed) arrangement: light must first pass through several layers before it hits the photoreceptors (cones and rods). The signals from the photoreceptors are transmitted via the optic nerve to the processing areas of the brain. The reason for the inverse arrangement is the evolutionary development of the retina, which is a protrusion of the brain.

The retina is approximately 0.2 to 0.5 mm thick.

Hypothalamus

The hypothalamus is considered the center of the autonomic nervous system, meaning it controls many motivational states and regulates vegetative aspects such as hunger, thirst, and sexual behavior. As an endocrine gland (which, unlike an exocrine gland, releases its hormones directly into the blood without a duct), it produces numerous hormones, some of which inhibit or stimulate the pituitary gland to release hormones into the blood.In this function, it also plays an important role in the response to pain and is involved in pain modulation.

Epiphysis

glandula pinalis/pineal gland

The epiphysis (pineal gland) is an unpaired component of the epithalamus (part of the diencephalon). It is a gland that secretes melatonin. Among other things, the epiphysis controls the "internal clock."

Recommended articles

The reins – not just anatomically

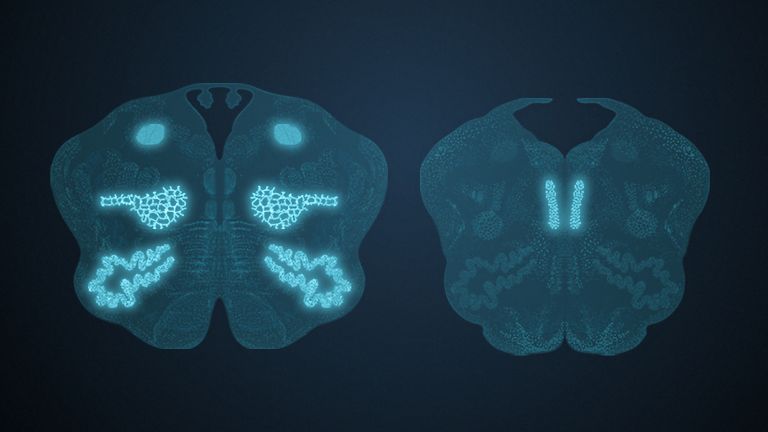

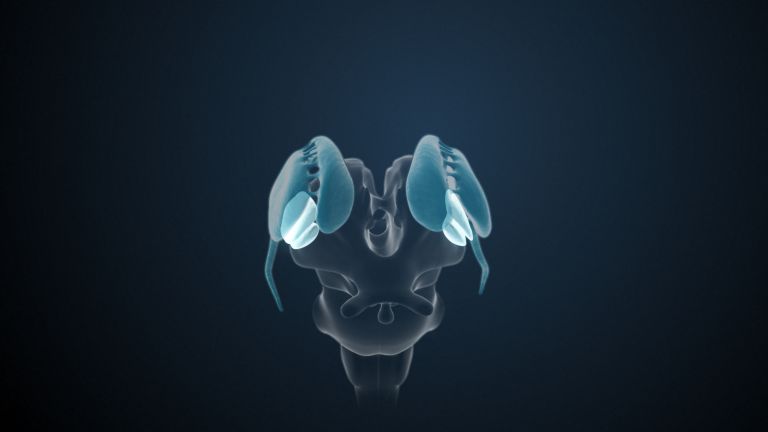

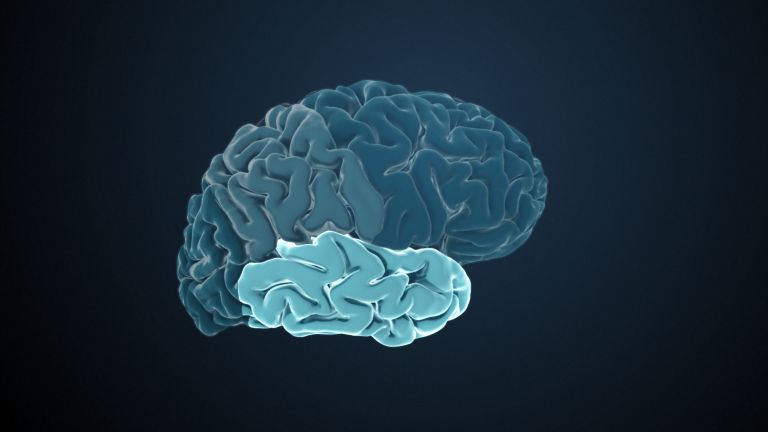

Although its shape might suggest otherwise, the habenula is not a strand of fibers, but rather a collection of core areas. The striae medullares, on the other hand, bring fibers from the septal nuclei of the limbic system, the preoptic nuclei, and the Amygdala complex into this region. These fibers run into the reins. At the transition between the two lie the nuclei habenulares, the reins nuclei. Despite their small size, they have surprisingly far-reaching functions that can influence the entirety of our behavior, right down to our decision-making.

The lateral habenula influences the reward system by inhibiting it when the result does not meet expectations. It thus also plays a role in corresponding learning processes, the stress response with flight or fight, and even the processing of pain. It even becomes active in Fear conditioning All of this is extremely useful when it comes to adapting to changes in the environment. However, it can also overshoot the mark – if the reward center is inhibited too much, meaning that too little Dopamine and Serotonin are released, the result can be anhedonia and even depression.

The medial habenula has similar, almost even more far-reaching competencies: it regulates moods, processes negative emotions, and motivates reactions to unpleasant and painful situations. In doing so, it significantly influences higher brain functions such as decision-making and attention. However, it also plays a role in withdrawal and relapse into addiction.

Amygdala

corpus amygdaloideum

An important core area in the temporal lobe that is associated with emotions: it evaluates the emotional content of a situation and reacts particularly to threats. In this context, it is also activated by pain stimuli and plays an important role in the emotional evaluation of sensory stimuli. Inaddition, it is involved in linking emotions with memories, emotional learning ability, and social behavior. The amygdala is part of the limbic system.

lateral

A positional term – lateral means "towards the side." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction at right angles to the neural axis, i.e., to the right or left.

Fear conditioning

The linking of a neutral stimulus to a stimulus that triggers fear – for example, first a soft sound, then a loud, frightening noise. After conditioning, the presentation of the neutral stimulus alone triggers fear.

Dopamine

Dopamine is an important neurotransmitter in the central nervous system that belongs to the catecholamine group. It plays a role in motor function, motivation, emotion, and cognitive processes. Disruptions in the function of this transmitter play a role in many brain disorders, such as schizophrenia, depression, Parkinson's disease, and substance dependence.

Serotonin

A neurotransmitter that acts as a messenger in the transmission of information between neurons at their synapses. It is primarily produced in the raphe nuclei of the brain stem and plays a key role in sleep and alertness, as well as emotional well-being.

Depression

A mental illness whose main symptoms are sadness and a loss of joy, motivation, and interest. Current classification systems distinguish between different types of depression.

medial

A positional term – medial means "towards the middle." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction toward the body, away from the sides.

attention

Attention

Attention serves as a tool for consciously perceiving internal and external stimuli. We achieve this by focusing our mental resources on a limited number of stimuli or pieces of information. While some stimuli automatically attract our attention, we can select others in a controlled manner. The brain also unconsciously processes stimuli that are not currently the focus of our attention.

Further reading:

- EFSA's position on melatonin-containing medicines; URL: http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsa-journal/doc/1467.pdf; to the website.

First published on August 28, 2011

Updated on October 9, 2025