The Thalamus dorsalis

The thalamus has many functions. Specific and non-specific nuclei are highly interconnected and control motor function, sensory perception, and, last but not least, the psyche. The thalamus is therefore much more than the oft-cited “gateway to consciousness.”

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Horst-Werner Korf

Published: 28.11.2025

Difficulty: serious

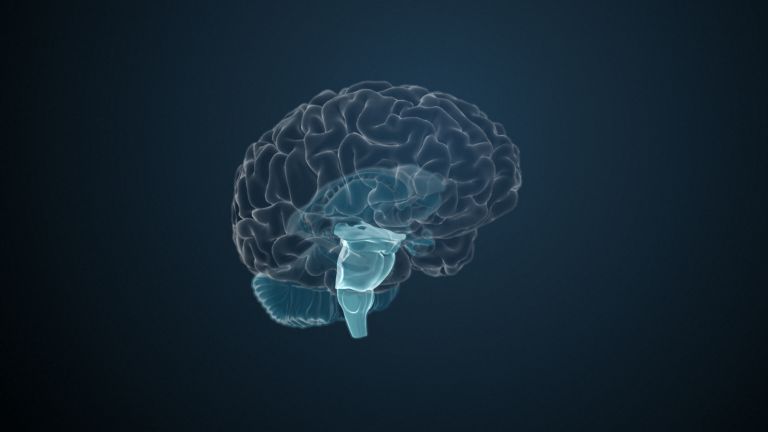

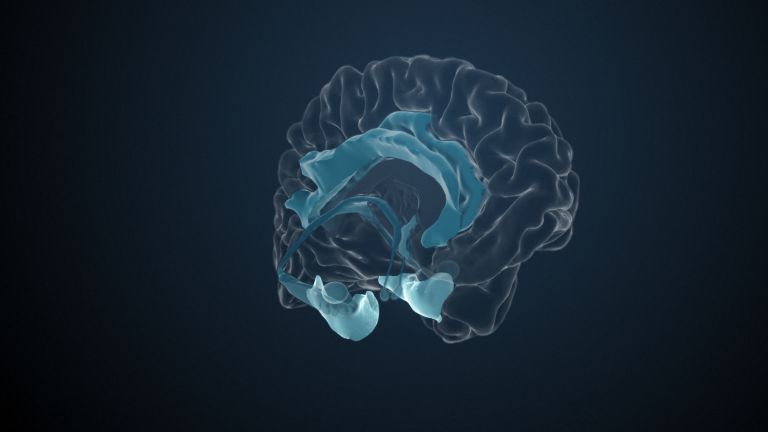

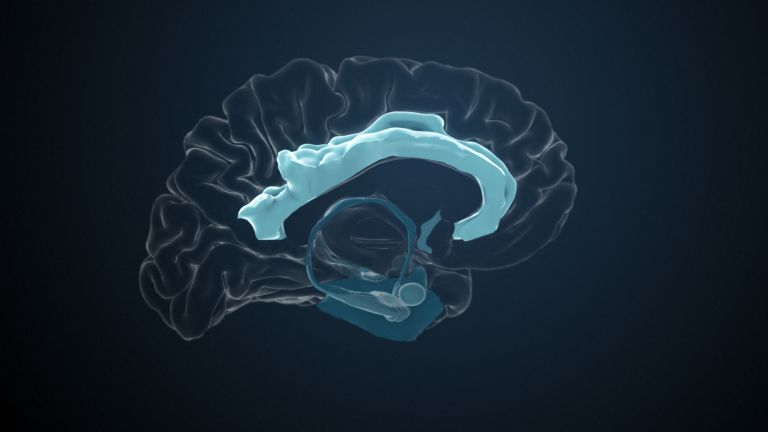

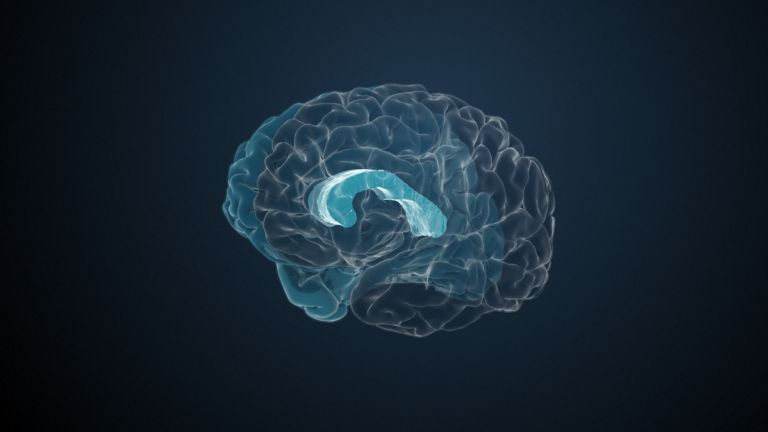

The thalamus is located in the walls of the Diencephalon and is its largest contiguous area. Certain thalamic nuclei are reciprocally connected to certain areas of the Cortex. Some thalamic nuclei specialize in transmitting sensory information to the cortex.

Diencephalon

The diencephalon (midbrain) includes the thalamus and hypothalamus, among other structures. Together with the cerebrum, it forms the forebrain. The diencephalon contains centers for sensory perception, emotion, and the control of vital functions such as hunger and thirst.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

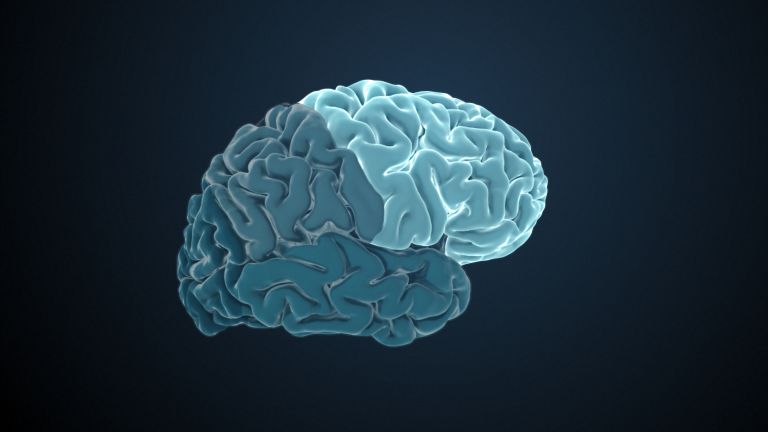

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

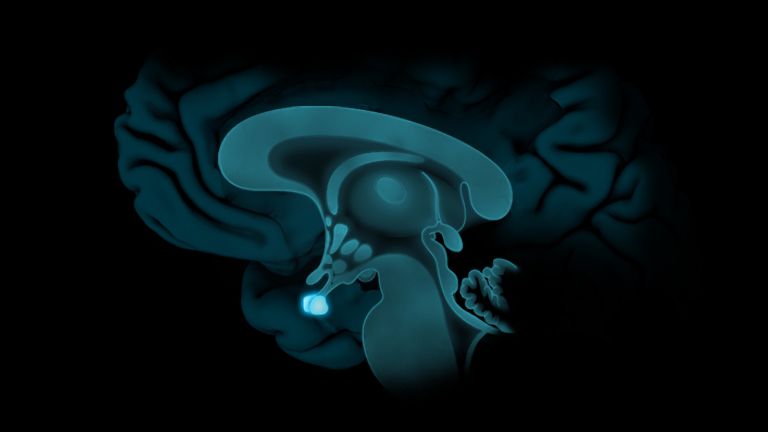

Anatomical terms are often very apt. Not so in the case of the thalamus. The Greek and Latin word “thalamus” actually means any room, a cavity, a living space. However, in modern anatomy, the thalamus is located on either side of a ventricular space – the third ventricle in the Diencephalon: it is part of the wall and not the cavity. The discrepancy arose because brain functions were originally sought in these very ventricles, where the human mind was thought to be distilled, comparable perhaps to good rum ... but that's another story.

In any case, this third ventricle of the diencephalon, at the base of which lie the conspicuous optic nerves, was aptly named the optic thalamus. When it was realized that it is the Gray matter in the walls of the brain that carries out its functions, the term changed accordingly. And when it was realized that only a small part of the thalamus is optical (the “tail” at its end, see below), the ‘opticus’ was dropped. And when it was further realized that the thalamus consists of an upper and a lower level, the upper level – which will be discussed here – was given the addition “dorsalis.” This clarification is hardly used anymore, because the lower “ventral thalamus” (consisting of the Subthalamic nucleus and globus pallidus) has completely different functions. So when anatomists simply say “thalamus,” they mean the thalamus dorsalis.

Diencephalon

The diencephalon (midbrain) includes the thalamus and hypothalamus, among other structures. Together with the cerebrum, it forms the forebrain. The diencephalon contains centers for sensory perception, emotion, and the control of vital functions such as hunger and thirst.

Gray matter

Grey matter refers to a collection of nerve cell bodies, such as those found in nuclei or in the cortex.

Subthalamic nucleus

Nucleus subthalamicus

Although the subthalamic nucleus is a nucleus of the subthalamus in the diencephalon, it is functionally closely integrated into the motor control of the basal ganglia. It plays a role in impulse control, movement control, and inhibition of unwanted movements. Damage to this nucleus can lead to temporary, uncontrolled, jerky movements of the extremities – known as ballism. Doctors have already achieved successful treatment outcomes in both obsessive-compulsive disorder and Parkinson's disease by artificially stimulating this region with a neuroimplant.

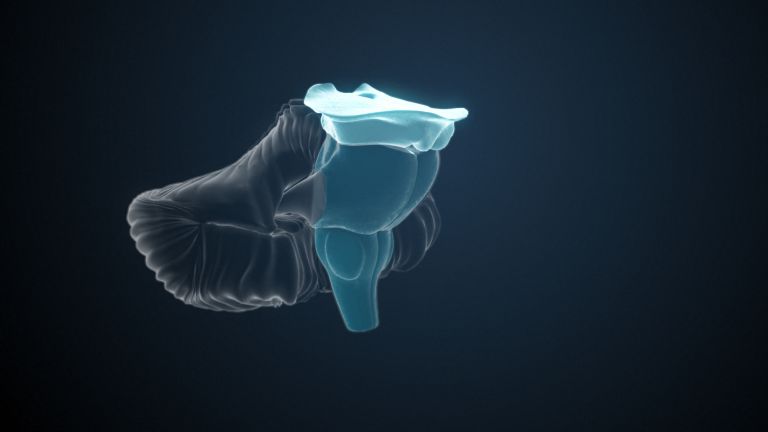

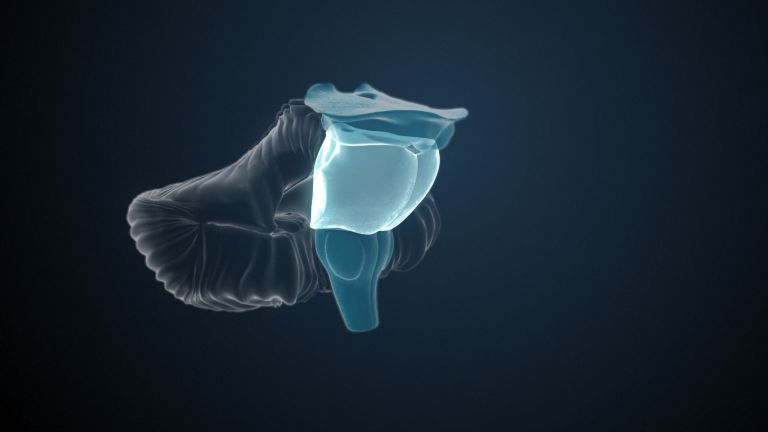

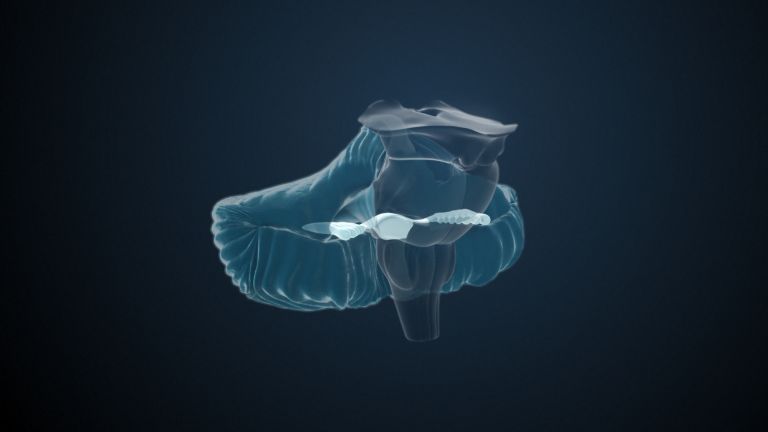

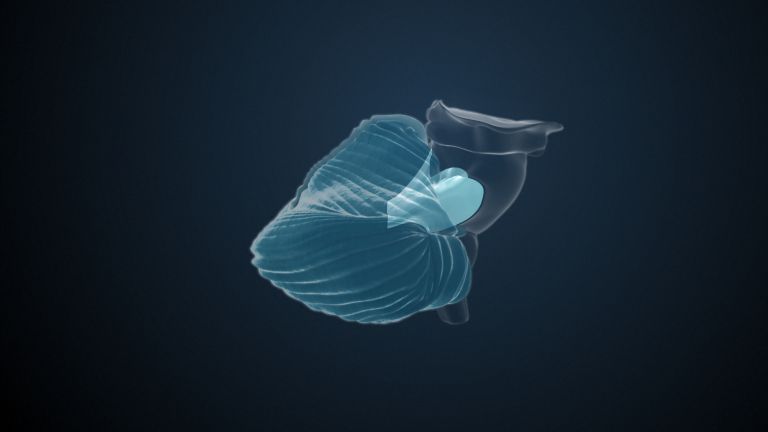

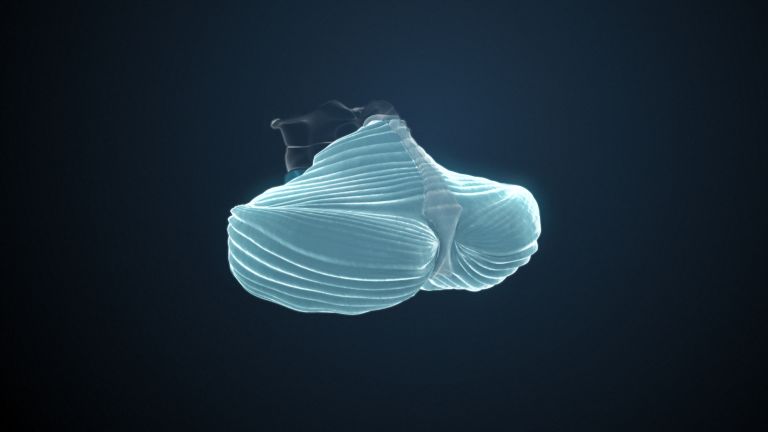

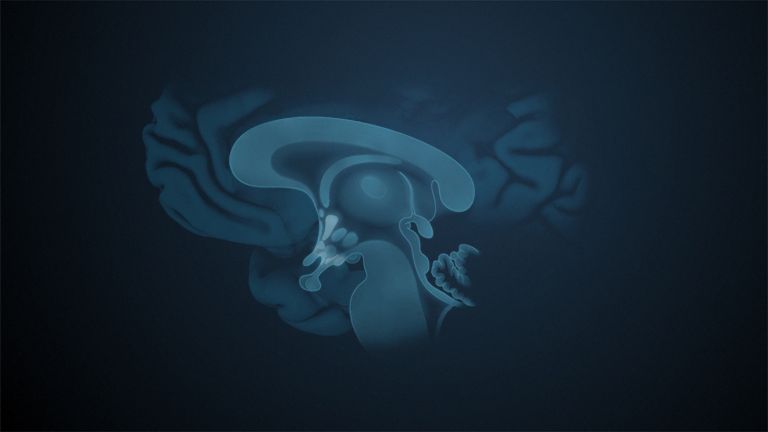

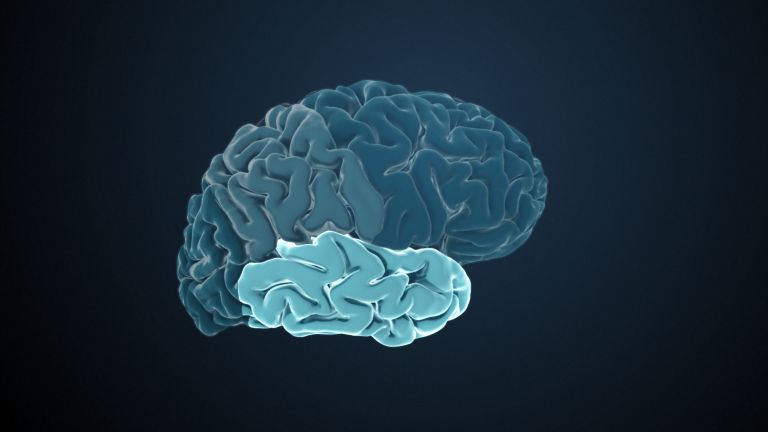

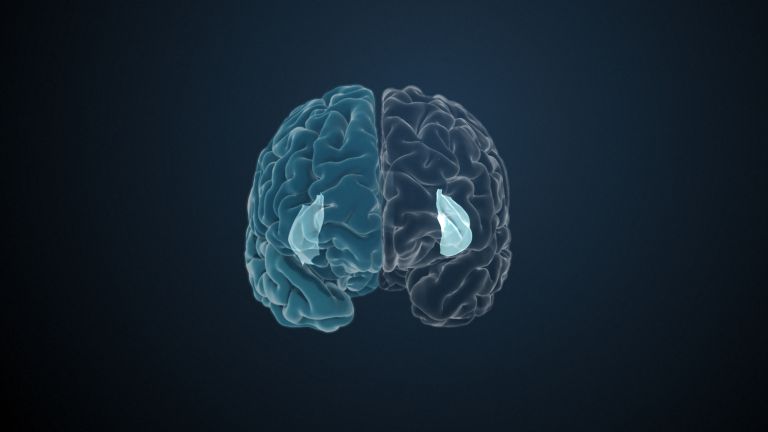

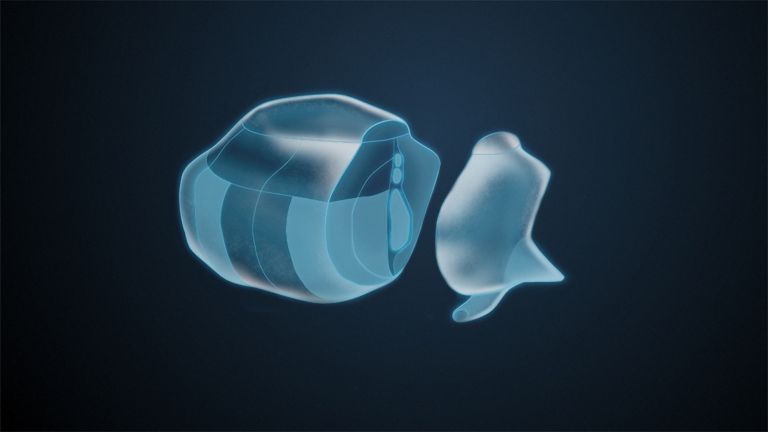

Strange shape

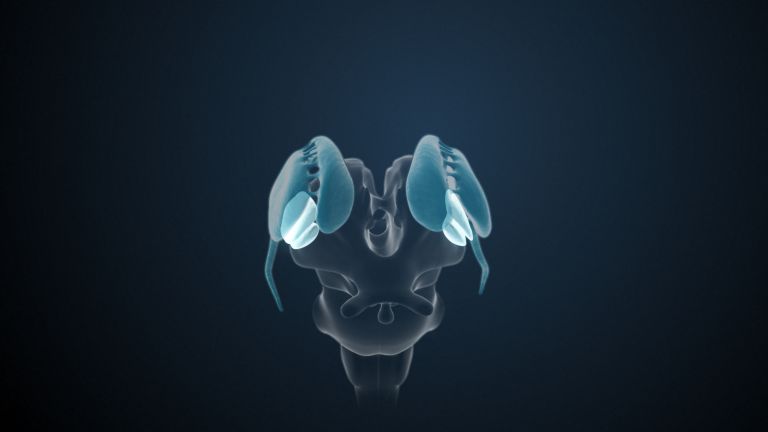

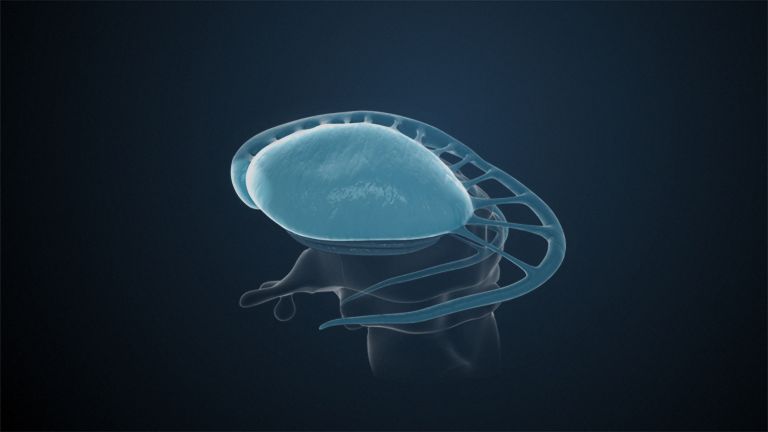

The two dorsal thalami are impressive structures, each about the size of a thumb. Their shape is a little strange; they resemble clumsy drops with their blunt heads pointing toward the forehead and their short stubby tails at the rear bent downward and outward. The body of the drop is the actual thalamus, the transition region to the stubby tail is called the pulvinar, and the tail itself is called the metathalamus, i.e., the post-thalamus, which consists of two knee bumps, the lateral and medial geniculate bodies (“genu” is Latin for “knee”). The actual thalamus, the drop, consists of many individual nuclei with different functions, making it one of the most complex structures in the brain.

dorsal

The positional term dorsal means "towards the back." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction perpendicular to the neural axis, i.e., upwards towards the head or backwards.

In animals that do not walk upright, the term is simpler, as it always means toward the back. Due to the upright posture of humans, the brain bends in relation to the spinal cord, making dorsal mean "upward."

lateral

A positional term – lateral means "towards the side." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction at right angles to the neural axis, i.e., to the right or left.

medial

A positional term – medial means "towards the middle." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction toward the body, away from the sides.

Basic function

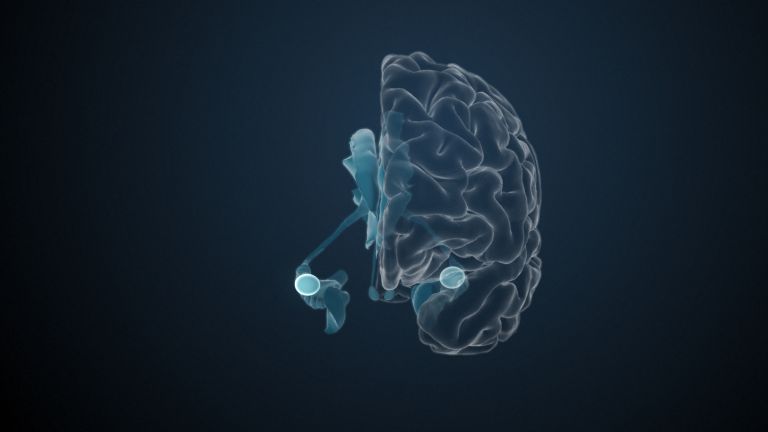

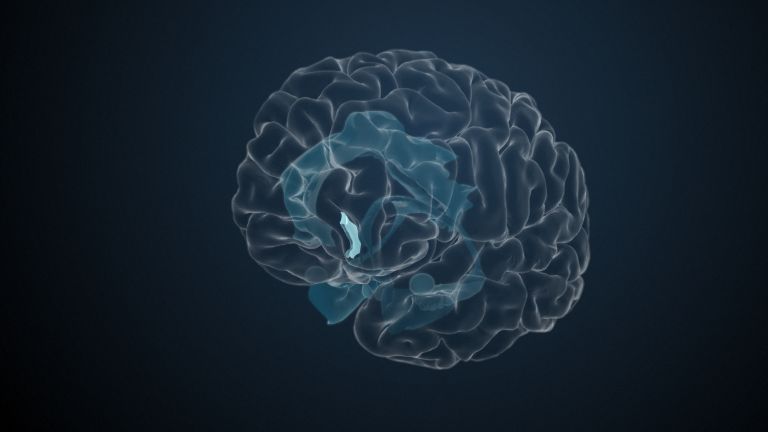

The thalamus is connected to the Cortex. “Patchy,” one might say, because certain areas of the thalamus send axons to certain areas of the cortex – and vice versa. The pattern of these connections – i.e., “who with whom” – is extremely stable and the same in all humans (and many animals). Accordingly, they are referred to as “specific thalamic nuclei.” They can also be understood as “cortical agents”: they carry information from the sensory systems, the eyes, the ears, the skin, the muscles and joints, the sense of pain and the sense of Taste to the cortex. The only exception is the sense of smell. But even that – if it is to become conscious – must ultimately pass through the thalamus.

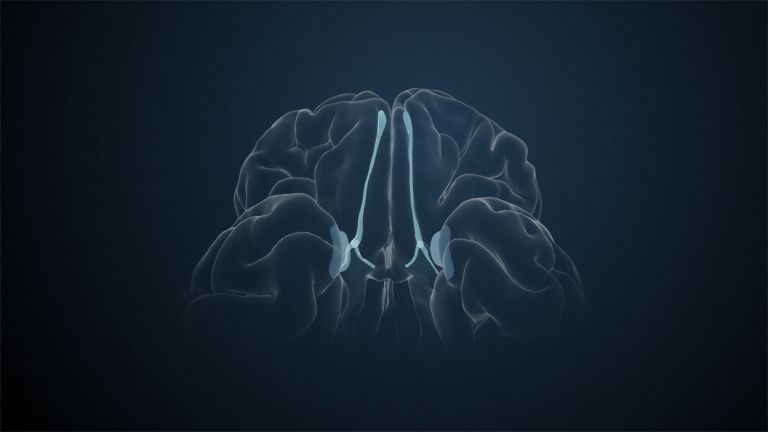

The fiber pathways of all these sensory systems converge in the thalamus at specific subnuclei – the Visual pathway at the lateral geniculate bodies, the Auditory pathway at the medial geniculate bodies. The remaining sensory pathways mainly run to the rear sides of the thalamus itself. In these subnuclei of the thalamus, synaptic switching then takes place to the last Neuron of the corresponding sensory pathway. The Axon of this neuron then runs to the respective primary sensory cortex area – and this area then sends axons back to “its” thalamic nucleus.

However, these genuinely sensory nuclei of the thalamus make up only a small part of its total mass. The other nuclei are less “agents” of the cortex than “mirrors” of it. They also send axons to specific, circumscribed areas of the cortex – but their main input does not come from the sensory periphery, but from the cortex itself, either directly – because, as mentioned above, every area of the cortex that receives thalamic inputs sends axons back – or indirectly, via loops. It would therefore be an oversimplification to refer to the thalamus – as is often done – merely as the “gateway to consciousness”: it is much more than just the “conveyor” of sensory information.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Taste

The sensory impression we refer to as "taste" results from the interaction between our senses of smell and taste. In terms of sensory physiology, however, "taste" is limited to the impression conveyed to us by the taste receptors on the tongue and in the surrounding mucous membranes. It is currently assumed that there are five different types of taste receptors that specialize in the taste qualities sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami. In 2005, scientists also identified possible taste receptors for fat, whose role as a distinct taste quality is still being investigated.

Visual pathway

The visual pathway refers to the network of nerve cells involved in visual perception. In mammals, it runs from the retinal ganglion cells in the eye – as the optic nerve to the optic chiasm, then as the visual tract – via the only switching point in the lateral geniculate nucleus to the primary visual cortex.

lateral

A positional term – lateral means "towards the side." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction at right angles to the neural axis, i.e., to the right or left.

Auditory pathway

The auditory pathway refers to the nerve fibers that transmit acoustic information from the inner ear to the primary auditory cortex. In humans, the auditory pathway consists of five switching points: the spiral ganglion, the auditory nuclei in the brainstem, the inferior colliculus, the medial geniculate body of the thalamus, and the primary auditory cortex.

medial

A positional term – medial means "towards the middle." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction toward the body, away from the sides.

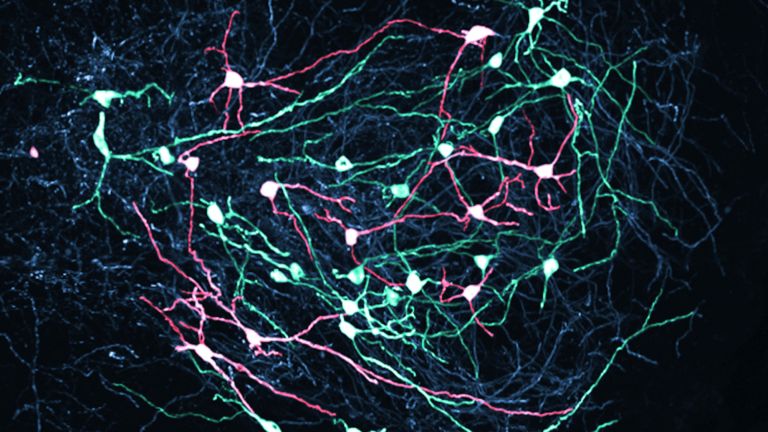

Neuron

A neuron is a specialized cell in the nervous system that is responsible for processing and transmitting information. It receives signals via its dendrites and transmits them via its axon. Transmission occurs electrically within the neuron and, between neurons, usually chemically via synapses.

Axon

axon

The axon is the extension of the nerve cell that is responsible for conducting nerve impulses to the next cell. An axon can branch out many times, reaching a large number of downstream nerve cells. It can be more than a meter long. The axon ends in one or more synapses.

Nucleus

In cell biology, the nucleus in a cell is the cell nucleus, which contains the chromosomes, among other things. In neuroanatomy, the nucleus in the nervous system refers to a collection of cell bodies – known as gray matter in the central nervous system and ganglia in the peripheral nervous system.

More specifically

Let's start at the back with the metathalamus, the “outwardly curved stub tail.” It is not completely smooth, but slightly bumpy, which is why we distinguish between the lateral geniculate Nucleus (LGN) and the medial geniculate nucleus (MGN). As already mentioned, the Auditory pathway ascends to the CGM, while the Optic tract descends to the CGL. And just to illustrate the relationship between sensory and cortical input with an example: the CGL – after all, the main switching point for visual signals from the Retina on their way to the Primary visual cortex at the back of the head – actually receives only 10 percent of its inputs from the retina. The other 90 percent come from the primary Visual cortex It is assumed that a selection of the transmitted information already takes place at this unconscious level – recent studies show that certain layers of the visual Cortex receive thalamic inputs, and other layers of the cortex then provide feedback to the CGL. In this way, the visual cortex modulates its own inputs.

The Pulvinar is also involved in visual processing and, in addition to cortical connections to large areas of the temporal and parietal lobes, also has connections to the CGL and the superior colliculi of the Midbrain – all centers involved in the processing of visual information.

Things get a little confusing in the thalamus itself, i.e., in the actual body of the “drop.” A distinction is made between an anterior group of nuclei (nuclei anteriores), which projects to the cingulate gyrus, a group of nuclei located at the ventricle (nuclei mediales), which is connected to the frontal lobe, and a large lateral group of nuclei (nuclei laterales), which projects to the frontal and parietal lobes. Of all these nuclei, only one subnucleus of the Lateral nucleus group, the posterior ventrolateral nucleus, is genuinely sensory: the pathways of the bodily senses lead to it. Its axons, in turn, ascend to the Postcentral gyrus of the Parietal lobe All the other nuclei mentioned are involved in more or less complex feedback loops between the cortex and other areas of the brain.

lateral

A positional term – lateral means "towards the side." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction at right angles to the neural axis, i.e., to the right or left.

Nucleus

In cell biology, the nucleus in a cell is the cell nucleus, which contains the chromosomes, among other things. In neuroanatomy, the nucleus in the nervous system refers to a collection of cell bodies – known as gray matter in the central nervous system and ganglia in the peripheral nervous system.

medial

A positional term – medial means "towards the middle." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction toward the body, away from the sides.

Auditory pathway

The auditory pathway refers to the nerve fibers that transmit acoustic information from the inner ear to the primary auditory cortex. In humans, the auditory pathway consists of five switching points: the spiral ganglion, the auditory nuclei in the brainstem, the inferior colliculus, the medial geniculate body of the thalamus, and the primary auditory cortex.

Optic tract

tractus opticus

The optic tract refers to the optic nerve after half of the fibers have crossed sides at the optic chiasm. However, it still consists of the axons (long fiber-like extensions) of the retinal ganglion cells. Most of the optic tract ends in the lateral geniculate nucleus, while others end in the superior colliculi, among other places.

Retina

The retina is the inner layer of the eye covered with pigment epithelium. The retina is characterized by an inverse (reversed) arrangement: light must first pass through several layers before it hits the photoreceptors (cones and rods). The signals from the photoreceptors are transmitted via the optic nerve to the processing areas of the brain. The reason for the inverse arrangement is the evolutionary development of the retina, which is a protrusion of the brain.

The retina is approximately 0.2 to 0.5 mm thick.

Primary visual cortex

area striata

The part of the occipital lobe whose primary inputs originate from the visual system. According to Brodmann, who originally divided the cerebral cortex into 52 areas in 1909, the primary visual cortex is area 17.

Visual cortex

The visual cortex refers to the areas of the occipital lobe that are involved in processing visual information. These include the primary visual cortex and the associative visual cortices V1 to V5. According to Brodmann, the visual cortex comprises areas 17, 18, and 19.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Pulvinar

The pulvinar is a fairly large nucleus in the posterior thalamus that is connected to many visual centers. It appears to increase the excitability of cells in the visual cortex as soon as a stimulus is noticed. Some studies suggest that the pulvinar may also indirectly support language processing via cortical connections.

Midbrain

mecencephalon

The midbrain is the uppermost section of the brain stem. Its regions are located around the aqueduct, a canal filled with cerebrospinal fluid. Prominent structures include the tectum, tegmentum, and substantia nigra.

frontal

An anatomical position designation – frontal means "towards the forehead," i.e., at the front.

Lateral nucleus

nucleus lateralis

The lateral nucleus belongs to the basolateral nucleus group of the amygdala. The basolateral amygdala is the largest part of the amygdala. It receives sensory information from the temporal lobe and neuromodulatory signals from the VTA, locus coeruleus, and basal forebrain, processes them, and sends them to the central nucleus. It is important for emotional learning and fear conditioning.

posterior

A positional term – posterior means "towards the back, located at the rear." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction towards the tail.

Postcentral gyrus

Gyrus postcentralis

The postcentral gyrus is the fold on the surface of the cerebrum located immediately behind the central sulcus. It contains the primary somatosensory cortex, where touch, pressure, temperature, and proprioceptive stimuli are processed.

Parietal lobe

Lobus parietalis

The parietal lobe is one of the four large lobes of the cerebral cortex. It is located behind the frontal lobe and above the occipital lobe. Somatosensory processes take place in its anterior region, while sensory information is integrated in its posterior region, enabling the handling of objects and spatial orientation. In addition, the parietal lobe is involved in attention, the recognition of body parts and objects, as well as linguistic and mathematical abilities.

Recommended articles

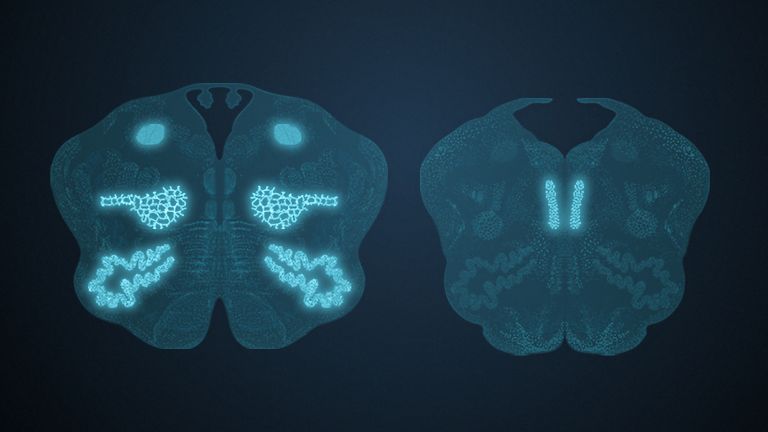

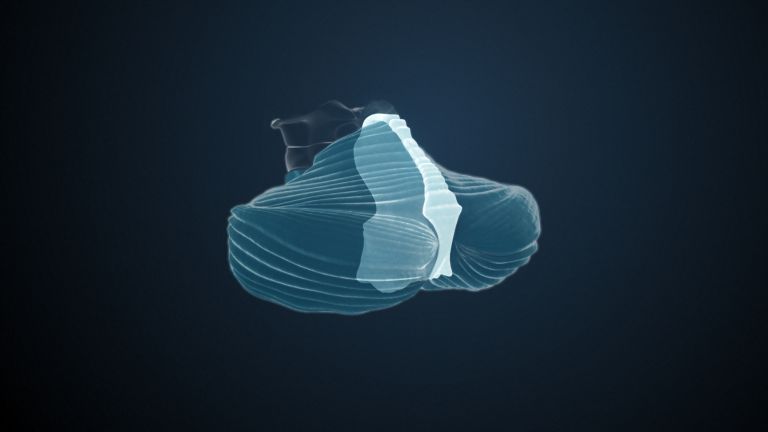

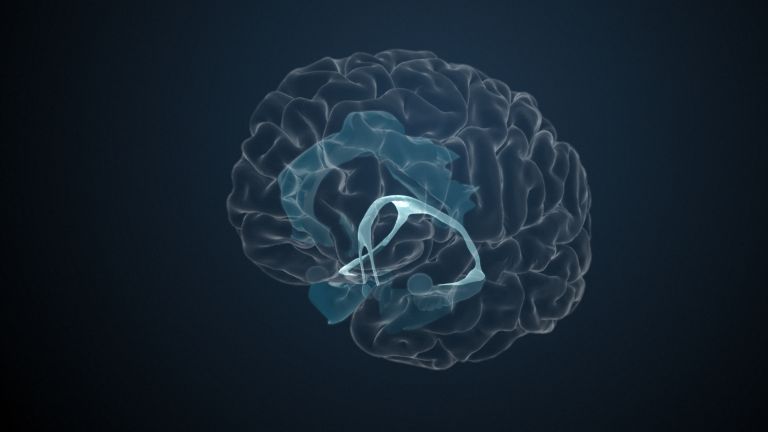

Non-specific

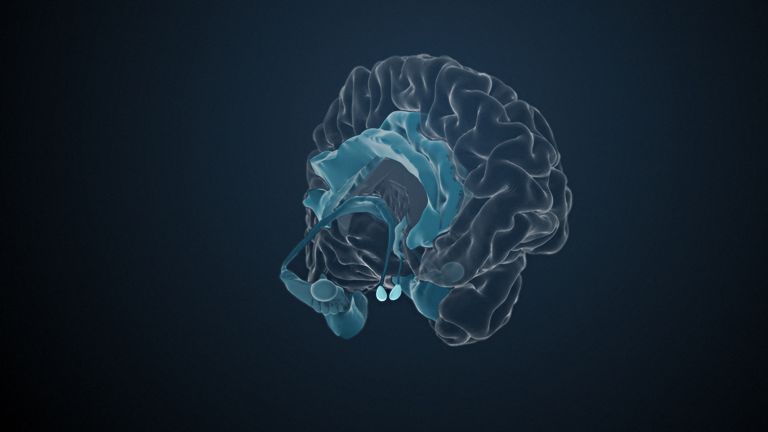

All of the above-mentioned nuclei maintain massive connections to specific, circumscribed areas of the Cortex. They are therefore also called “specific” nuclei.

The “non-specific nuclei” have less pronounced connections to the cortex, or none at all. One of them is the reticular Nucleus. It surrounds the lateral surface of the thalamus like a shell and contains inhibitory GABAergic neurons that send their axons into the thalamus itself. It is believed to be involved in attention control.

Other non-specific nuclei are located inside the thalamus itself, in thin lamellae of white matter that run through and divide it. These so-called “intralaminar nuclei” send their axons mainly to the basal ganglia, but also have diffuse, widely scattered cortical projections. Their inputs come primarily from the formation reticularis of the Brain stem and – primarily motor – from the Basal ganglia and the cerebellum.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Nucleus

In cell biology, the nucleus in a cell is the cell nucleus, which contains the chromosomes, among other things. In neuroanatomy, the nucleus in the nervous system refers to a collection of cell bodies – known as gray matter in the central nervous system and ganglia in the peripheral nervous system.

lateral

A positional term – lateral means "towards the side." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction at right angles to the neural axis, i.e., to the right or left.

attention

Attention

Attention serves as a tool for consciously perceiving internal and external stimuli. We achieve this by focusing our mental resources on a limited number of stimuli or pieces of information. While some stimuli automatically attract our attention, we can select others in a controlled manner. The brain also unconsciously processes stimuli that are not currently the focus of our attention.

white matter

The white matter refers to the myelinated fibers of the nervous system that connect one neuron to another. The white color is caused by the myelin sheath surrounding the fibers.

Brain stem

truncus cerebri

The "trunk" of the brain, to which all other brain structures are "attached," so to speak. From bottom to top, it comprises the medulla oblongata, the pons, and the mesencephalon. It transitions into the spinal cord below. It is a center for vital functions such as breathing and heartbeat and contains ascending and descending pathways between the cerebrum, cerebellum, and spinal cord.

Basal ganglia

Nuclei basales

The basal ganglia are a group of subcortical nuclei (located beneath the cerebral cortex) in the telencephalon. The basal ganglia include the globus pallidus and the striatum, and, depending on the author, other structures such as the substantia nigra and the subthalamic nucleus. The basal ganglia are primarily associated with voluntary motor function, but they also influence motivation, learning, and emotion.

Cerebellum

Cerebellum

The cerebellum is an important part of the brain, located at the back of the brain stem and below the occipital lobe. It consists of two cerebellar hemispheres covered by the cerebellar cortex and plays an important role in motor processes, among other things. It develops from the rhombencephalon.

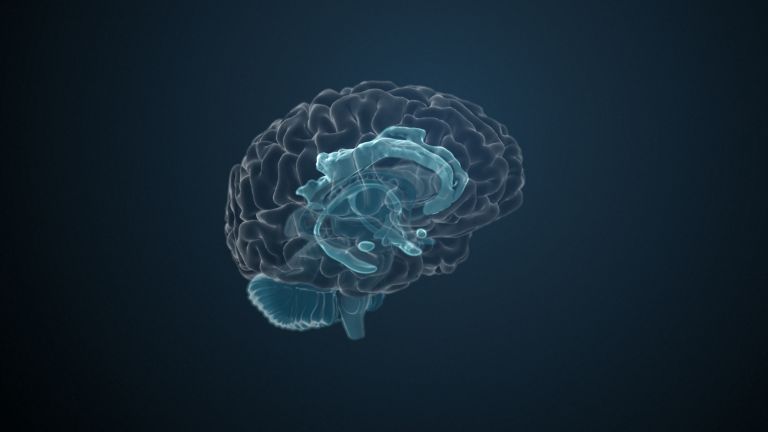

Deficits

In line with the manifold tasks of the thalamus, deficits are the effects of lesions. And some of them are very specific: if, for example, the ventral posterolateral Nucleus is affected, this leads to disturbances in surface and deep sensitivity – and the feeling of swelling and heaviness in the extremities can be the result. Pain, motor phenomena, or paralysis are possible. Fortunately, extensive damage to the Dorsal thalamus is very rare. But when it does occur, everything goes wrong – there are not only sensory deficits, but also severe motor deficits. And, above all, psychological problems.

ventral

A positional term – ventral means "towards the abdomen." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction perpendicular to the neural axis, i.e., downwards or forwards.

In animals (that do not walk upright), the term is simpler, as it always means toward the abdomen. Due to the upright posture of humans, the brain bends in relation to the spinal cord, making ventral mean "forward."

Nucleus

In cell biology, the nucleus in a cell is the cell nucleus, which contains the chromosomes, among other things. In neuroanatomy, the nucleus in the nervous system refers to a collection of cell bodies – known as gray matter in the central nervous system and ganglia in the peripheral nervous system.

dorsal

The positional term dorsal means "towards the back." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction perpendicular to the neural axis, i.e., upwards towards the head or backwards.

In animals that do not walk upright, the term is simpler, as it always means toward the back. Due to the upright posture of humans, the brain bends in relation to the spinal cord, making dorsal mean "upward."

Dorsal thalamus

Thalamus dorsals

The thalamus is the largest structure in the diencephalon and is located above the hypothalamus. The thalamus is considered the "gateway to consciousness" because its nuclei are the transit station for all information to the cortex (cerebral cortex) – except for olfactory information, which first reaches the olfactory areas of the brain directly. At the same time, they also receive massive cortical inputs so it might be better to regard this a thalami-cortical system. The nuclei of the thalamus are grouped together. The term "gateway to consciousness" also refers to attention control, sleep-wake regulation, and consciousness modulation by the intralaminar nuclei.

First published on August 23, 2011

Last updated on November 28, 2025