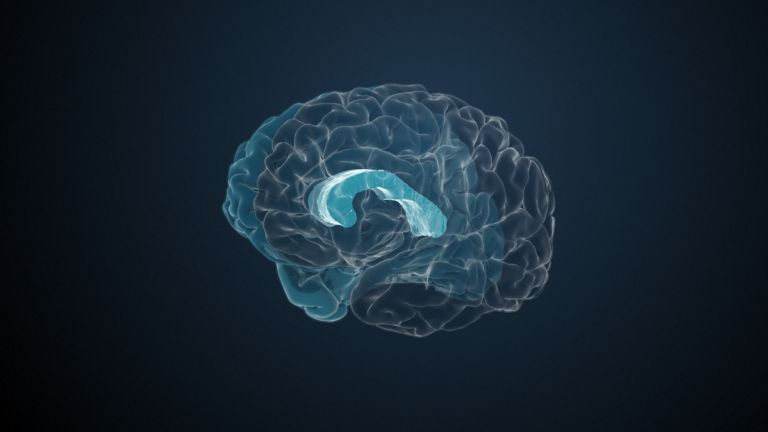

The Cerebellar Hemispheres

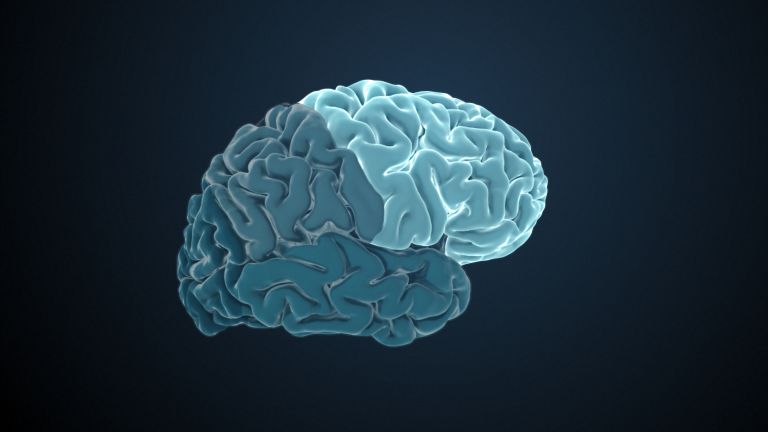

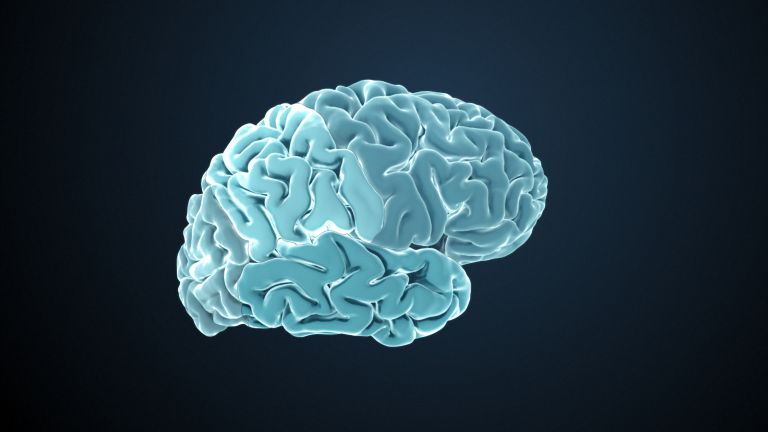

The two bulging, heavily folded hemispheres of the cerebellum primarily coordinate voluntary movements. They are particularly pronounced in primates, and their surface area is almost as large as that of the cerebrum.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Hans-Dieter Hofmann, Prof. Dr. Andreas Vlachos

Published: 20.09.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

- The Cerebellum is divided into two hemispheres.

- It is heavily folded and crisscrossed with numerous elevations, convolutions, and furrows, which serve to increase its surface area.

- Although it accounts for only ten percent of the weight of the cerebrum, it covers three-quarters of its surface and contains most of the brain's nerve cells.

- The main task of the cerebellum is to control, coordinate, and refine movements.

- It does this through a Cortex rich in nerve cells with multiple connections: The cortex constantly keeps the Cerebellar nuclei inside under its inhibitory control, thus regulating their flow of information to other areas of the brain such as the Brain stem and, via the thalamus, to the cerebral cortex.

Cerebellum

Cerebellum

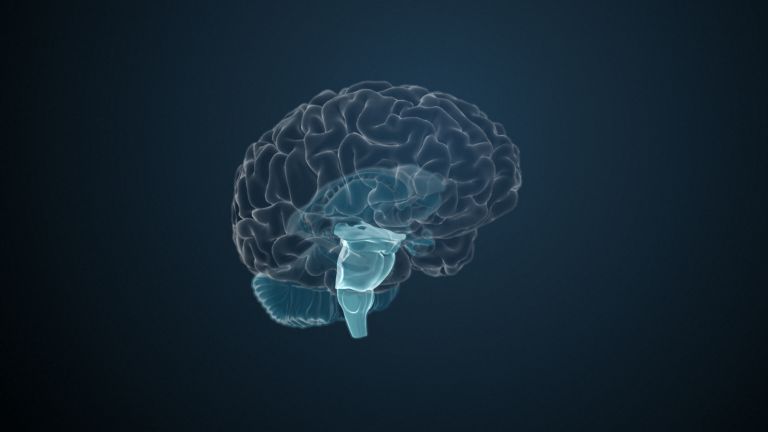

The cerebellum is an important part of the brain, located at the back of the brain stem and below the occipital lobe. It consists of two cerebellar hemispheres covered by the cerebellar cortex and plays an important role in motor processes, among other things. It develops from the rhombencephalon.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Cerebellar nuclei

A group of four paired nuclei located in the white matter of the cerebellum: the dentate nucleus, emboliform nucleus, globose nucleus, and fastigial nucleus. Functionally, the cerebellar nuclei are associated with motor tasks.

Brain stem

truncus cerebri

The "trunk" of the brain, to which all other brain structures are "attached," so to speak. From bottom to top, it comprises the medulla oblongata, the pons, and the mesencephalon. It transitions into the spinal cord below. It is a center for vital functions such as breathing and heartbeat and contains ascending and descending pathways between the cerebrum, cerebellum, and spinal cord.

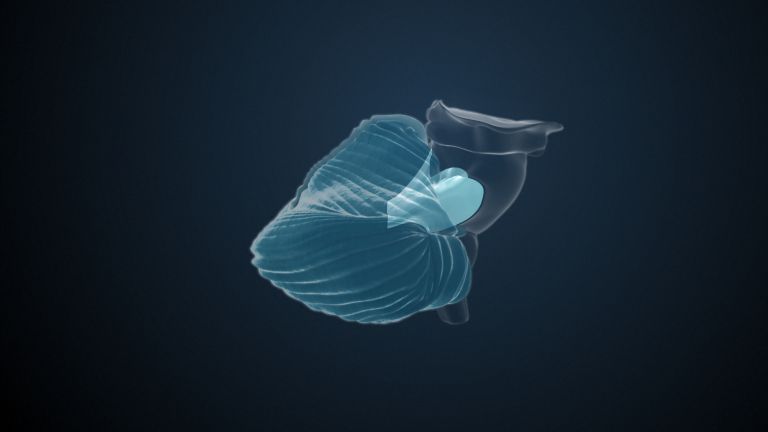

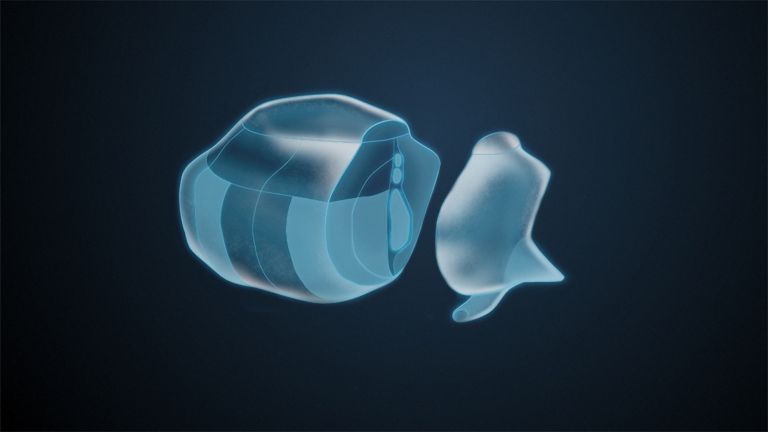

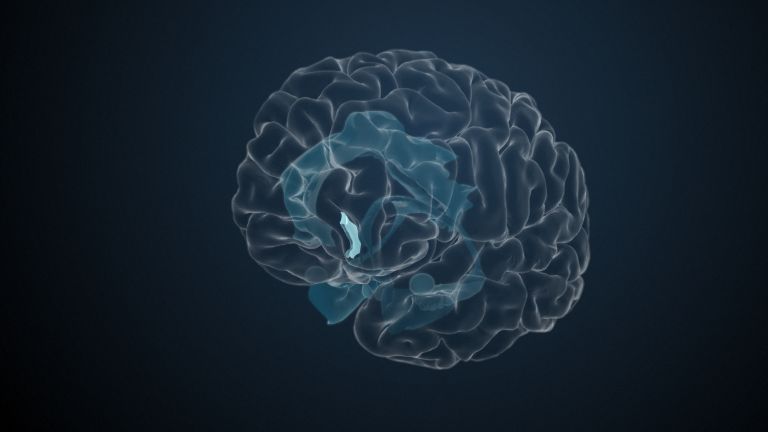

Just like the cerebrum, the Cerebellum is divided into two hemispheres and uses the principle of surface enlargement to its advantage. The Cortex is not smooth, but heavily foldedwith numerous elevations, the gyri, and deep valleys, the sulci. However, the Latin names for these features differ between the Cerebrum and cerebellum; in the cerebrum, they are called gyri and sulci, while in the cerebellum, they are called foliae and fissurae. And there are further differences: The many furrows of the cerebellum run almost parallel to each other, and its cortex is much more finely fissured, with narrower convolutions.

The cerebellum clearly wins the competition for the most effective surface enlargement: it weighs only ten percent of the cerebrum but has almost three-quarters of its surface area. If stretched out, the cerebellum would be almost 2 meters long. And although it accounts for only about one-tenth of the total brain mass, it contains the largest proportion of all nerve cells in the brain. Most of these are tiny granule cells, which are involved in huge numbers in the processing and fine-tuning of movements.

In mammals, and especially in humans, the Cerebellar hemispheres are particularly pronounced compared to lower vertebrates: in the course of evolution from reptiles to primates, they have become increasingly important.

Cerebellum

Cerebellum

The cerebellum is an important part of the brain, located at the back of the brain stem and below the occipital lobe. It consists of two cerebellar hemispheres covered by the cerebellar cortex and plays an important role in motor processes, among other things. It develops from the rhombencephalon.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Cerebrum

telencephalon

The cerebrum comprises the cerebral cortex (gray matter), the nerve fibers (white matter), and the basal ganglia. It is the largest part of the brain. The cortex can be divided into four cortical areas: the temporal lobe, frontal lobe, occipital lobe, and parietal lobe.

Its functions include the coordination of perception, motivation, learning, and thinking.

Cerebellar hemispheres

Like the cerebrum, the cerebellum also has two hemispheres. The hemispheres are primarily responsible for finely tuned, purposeful movement control.

Structure and function

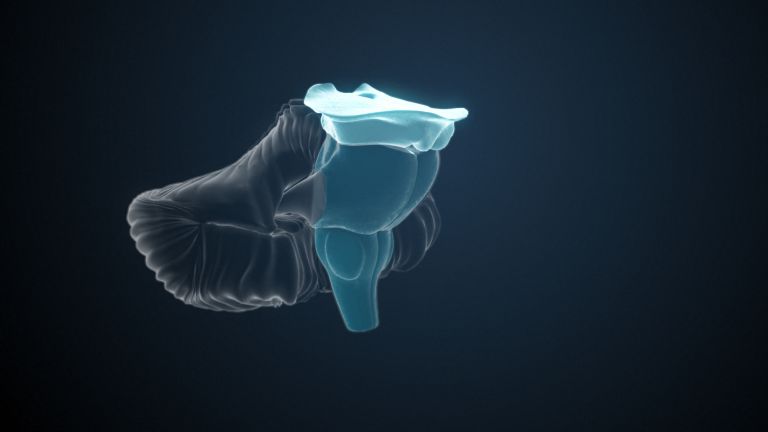

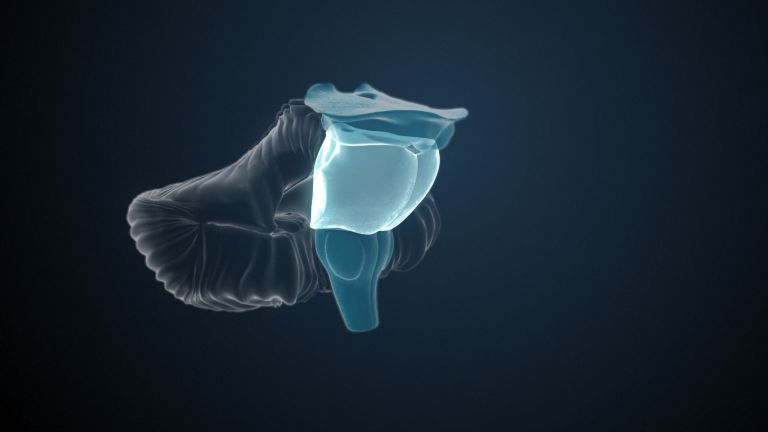

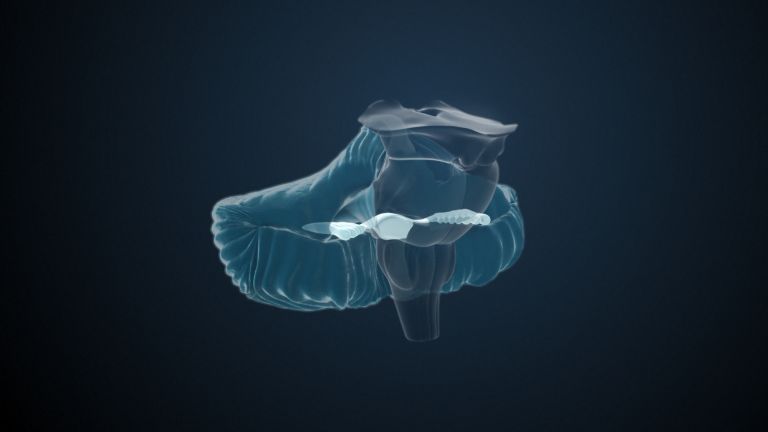

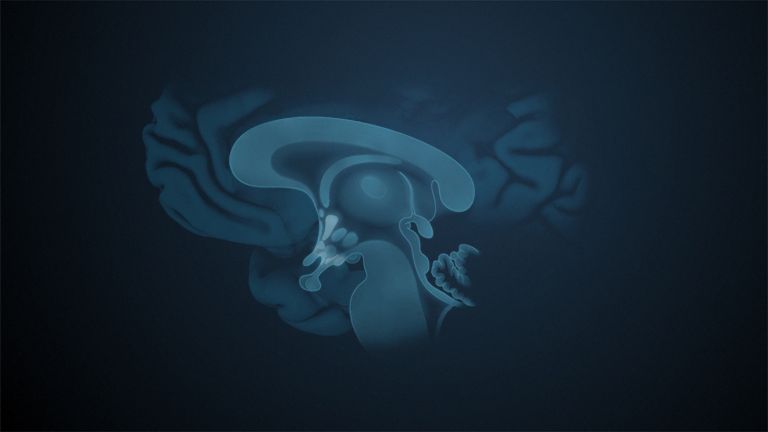

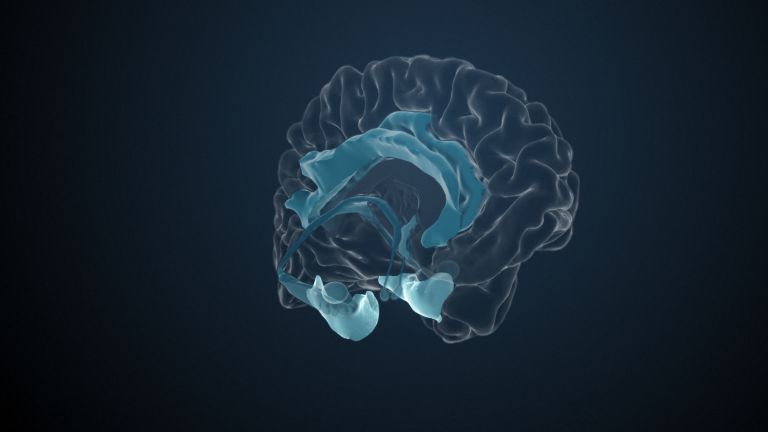

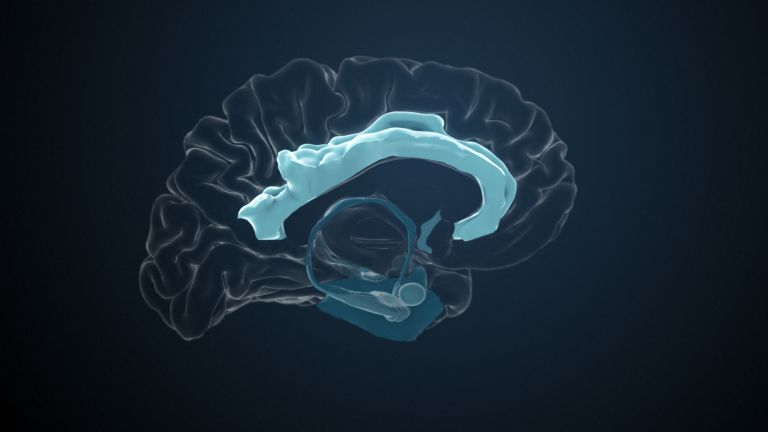

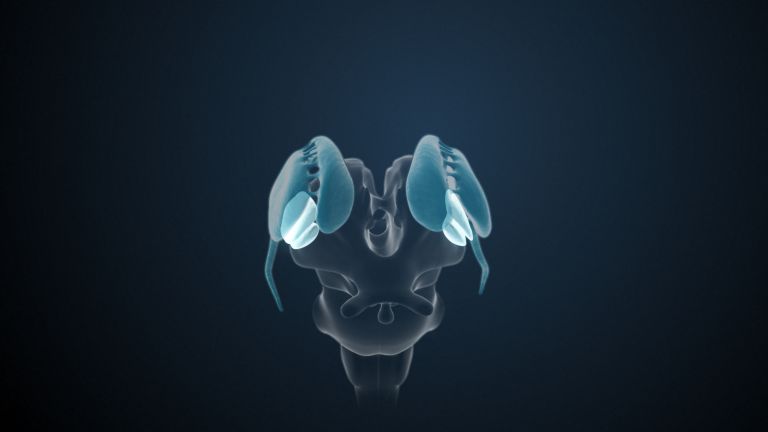

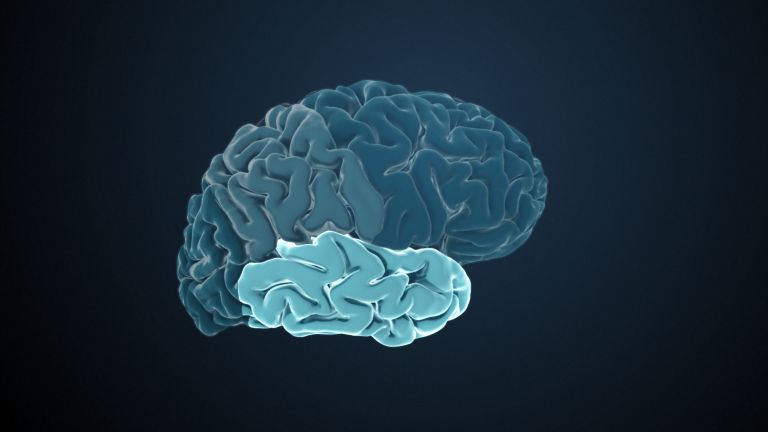

The Cerebellum lies below the hemispheres of the Cerebrum and behind the Brain stem As already mentioned, it is divided into two halves. Viewed from above and below, the two Cerebellar hemispheres vaguely resemble the bulging wings of a butterfly. They are separated from each other by the middle section, known as the Vermis. Towards the rear and bottom, where the Spinal cord exits the skull, the two cerebellar tonsils protrude. They are clinically significant because, in the event of increased intracranial pressure, they can be pressed against the brain stem in the cranial opening – with serious neurological consequences.

As with the cerebrum, the hemispheres are divided into lobes, known as lobi in Latin, which are separated from each other by larger sulci. Textbooks list the Latin names of numerous sulci, lobes, and lobules, which are named according to their location or shape – for example, “posterior lateral sulcus” or “crescent-shaped lobule” – or simply numbered. However, this division is usually not based on any functional order.

To understand the cerebellum, it is therefore more important to use a functional classification that also reflects its developmental history. The oldest part is the flocculonodular lobe, also known as the vestibulocerebellum. It is closely linked to the balance system and controls posture and Eye movements. The middle section, with the vermis and the adjacent hemispheres, forms the Spinocerebellum. It regulates the basic tension of the muscles and coordinates involuntary movements such as walking. Finally, the youngest and largest part of the cerebellum is formed by the lateral hemispheres, the pontocerebellum. It is particularly well developed in primates, closely connected to the cerebral cortex, and coordinates precise, voluntary movements, such as when we reach for a glass or play a musical instrument.

An external boundary between these functional parts cannot always be identified. In addition, all three systems work closely together by processing information from the spinal cord, the vestibular system, and the cerebral Cortex. The cerebellum itself does not generate movements. Rather, it monitors, corrects, and refines them. This ensures that actions are not only fluid, but also performed in a forward-looking, precise, and economical manner.

In addition to controlling ongoing movements, the cerebellum also plays a key role in motor learning. It remembers errors that occur during the execution of movements and adjusts the movement programs so that sequences become increasingly fluid and automatic.

Cerebellum

Cerebellum

The cerebellum is an important part of the brain, located at the back of the brain stem and below the occipital lobe. It consists of two cerebellar hemispheres covered by the cerebellar cortex and plays an important role in motor processes, among other things. It develops from the rhombencephalon.

Cerebrum

telencephalon

The cerebrum comprises the cerebral cortex (gray matter), the nerve fibers (white matter), and the basal ganglia. It is the largest part of the brain. The cortex can be divided into four cortical areas: the temporal lobe, frontal lobe, occipital lobe, and parietal lobe.

Its functions include the coordination of perception, motivation, learning, and thinking.

Brain stem

truncus cerebri

The "trunk" of the brain, to which all other brain structures are "attached," so to speak. From bottom to top, it comprises the medulla oblongata, the pons, and the mesencephalon. It transitions into the spinal cord below. It is a center for vital functions such as breathing and heartbeat and contains ascending and descending pathways between the cerebrum, cerebellum, and spinal cord.

Cerebellar hemispheres

Like the cerebrum, the cerebellum also has two hemispheres. The hemispheres are primarily responsible for finely tuned, purposeful movement control.

Vermis

Cerebellar vermis

The vermis is an unpaired structure of the cerebellum located on the midline. It primarily receives somatosensory inputs.

Spinal cord

medulla spinalis

The spinal cord is the part of the central nervous system located in the spine. It contains both the white matter of the nerve fibers and the gray matter of the cell nuclei. Simple reflexes such as the knee-jerk reflex are already processed here, as sensory and motor neurons are directly connected. The spinal cord is divided into the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral spinal cord.

cranial

A positional term – cranial means "towards the head." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction along the neural axis, i.e., forward.

In animals (without upright gait), the designation is simpler, as it always means forward. Due to the upright gait of humans, the brain bends in relation to the spinal cord, where cranial also means "upward."

lateral

A positional term – lateral means "towards the side." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction at right angles to the neural axis, i.e., to the right or left.

Eye

bulbus oculi

The eye is the sensory organ responsible for perceiving light stimuli – electromagnetic radiation within a specific frequency range. The light visible to humans lies in the range between 380 and 780 nanometers.

Spinocerebellum

The area of the cerebellum that includes the cerebellar vermis and its adjacent areas. Involved in muscle tone and walking movements.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Recommended articles

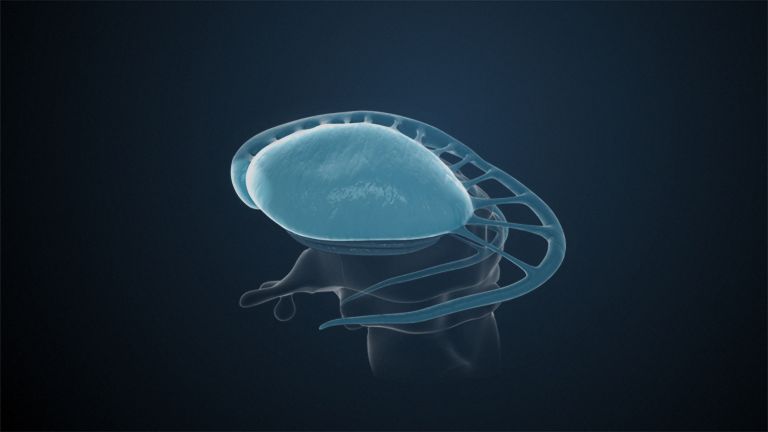

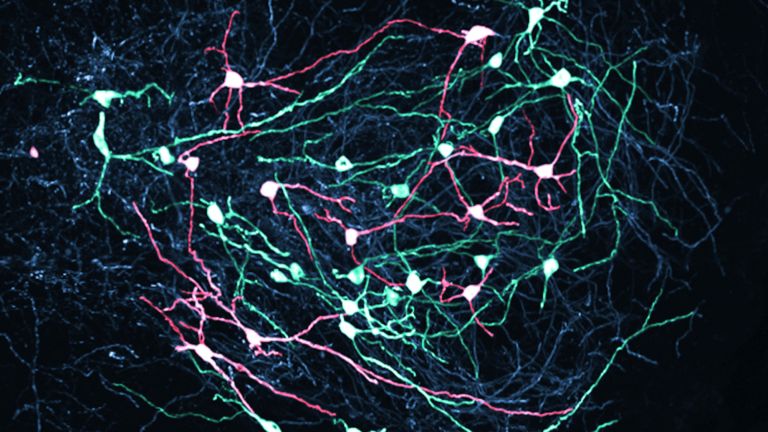

A closer look: cellular structure

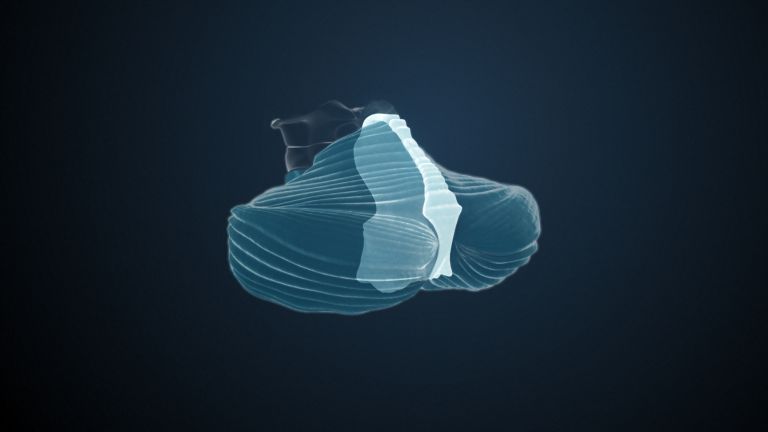

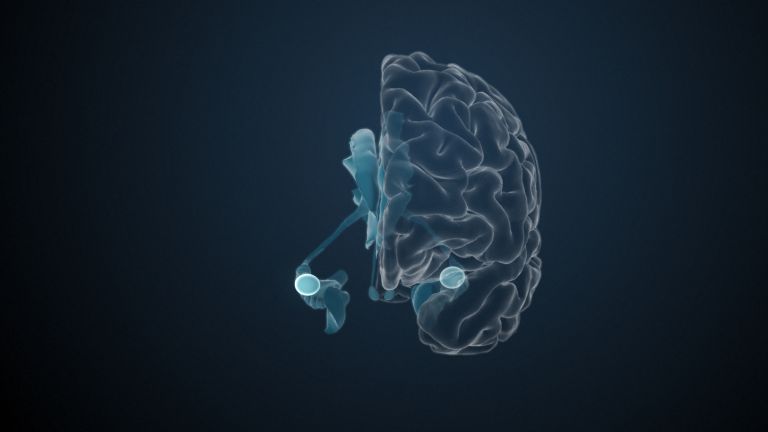

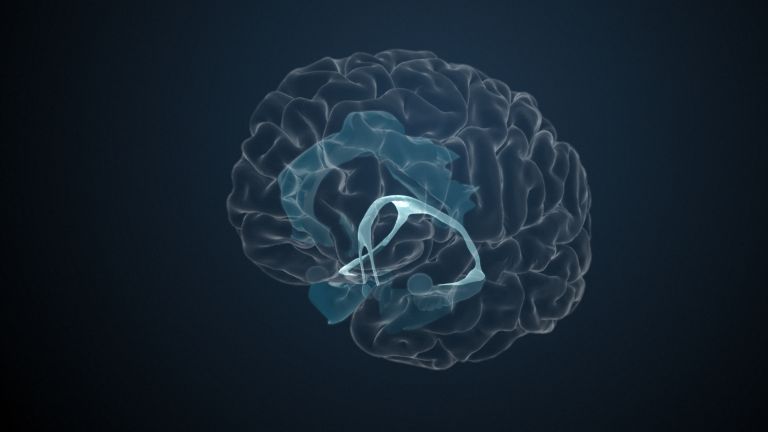

The Cerebellar cortex follows all the convolutions and, unlike the cerebral cortex, has an almost uniform structure throughout. It consists of three layers: the outer molecular layer, the middle Purkinje cell layer, and the inner granular layer. The molecular layer mainly contains the long extensions of nerve cells, including the so-called parallel fibers – thin axons of granule cells from the innermost layer – and the climbing fibers, which originate in the lower olivary body in the brain stem.

The Purkinje cell layer is only one cell layer thick, but it is striking: here, the large nerve cells of the Cerebellum are arranged in a row. Their widely branched dendrites protrude into the molecular layer and branch out there like the branches of a flat, disc-shaped tree. A single Purkinje cell can form connections to more than 100,000 parallel fibers – an impressive number of synapses. Their axons extend into the interior of the cerebellum to the nuclei located there. In total, the human cerebellum contains about 15 million Purkinje cells.

Finally, in the innermost layer, the granular layer, there are billions of tiny granule cells. They represent the largest contiguous population of nerve cells in the entire brain. Their axons ascend to the surface, where they split into a T-shape and run as parallel fibers. In doing so, they come into contact with the dendrites of hundreds of Purkinje cells.

This creates a network with an unimaginable number of connections – and yet the principle can be summarized simply: Only the Purkinje cells conduct signals out of the Cortex. They have an inhibitory effect on the Cerebellar nuclei Only when other inputs throttle the Purkinje cells can the nuclei become active and pass on information to the outside world. This principle ensures that movements do not become excessive. The cerebellum acts like a precise brake that regulates movements.

Cerebellar cortex

Cerebellar cortex

The cortex of the cerebellum, which, like that of the cerebrum, is composed of gray matter, or nerve cells. It consists of three layers and is highly folded, creating what are known as foliae, or leaves.

Purkinje cell

Purkinje cells are the main output cells of the cerebellar cortex and central switching points of the cerebellum. They have a dense, tree-like dendritic apparatus through which they receive information from thousands of parallel fibers and climbing fibers. Their axons are the only ones that extend out of the cerebellar cortex and project onto the nuclei of the cerebellum, from where signals are transmitted to motor centers. Purkinje cells are among the largest cell types in the cerebellum.

Cerebellum

Cerebellum

The cerebellum is an important part of the brain, located at the back of the brain stem and below the occipital lobe. It consists of two cerebellar hemispheres covered by the cerebellar cortex and plays an important role in motor processes, among other things. It develops from the rhombencephalon.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Cerebellar nuclei

A group of four paired nuclei located in the white matter of the cerebellum: the dentate nucleus, emboliform nucleus, globose nucleus, and fastigial nucleus. Functionally, the cerebellar nuclei are associated with motor tasks.

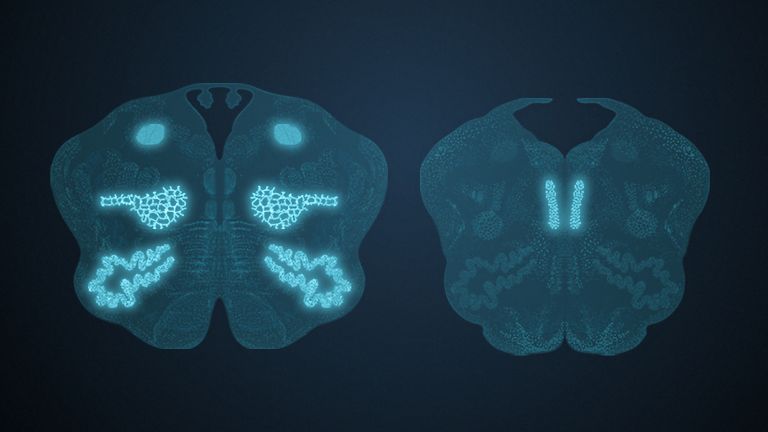

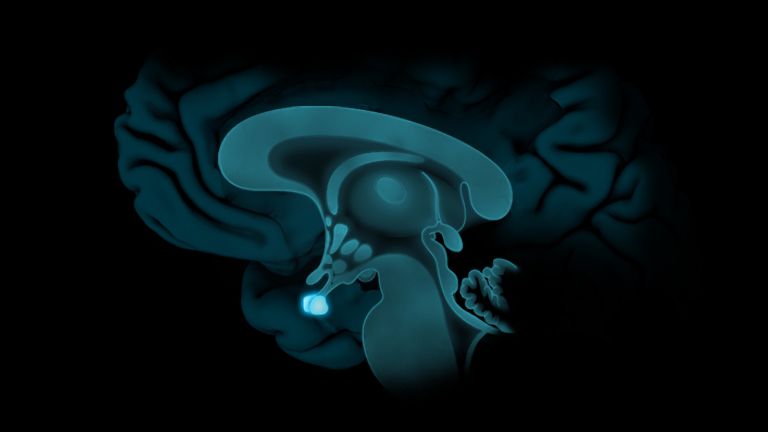

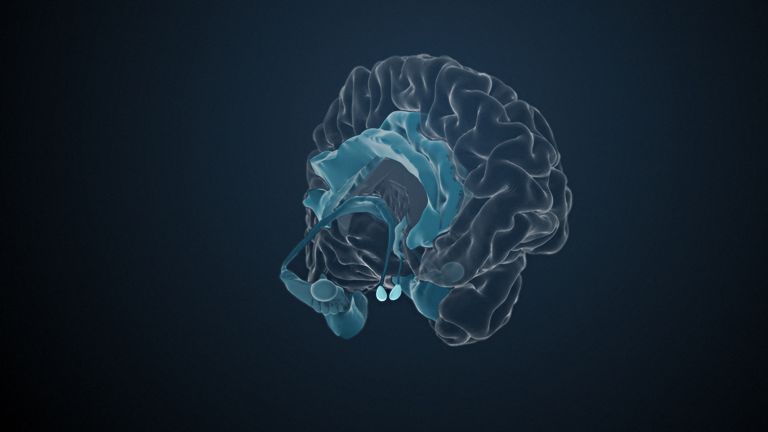

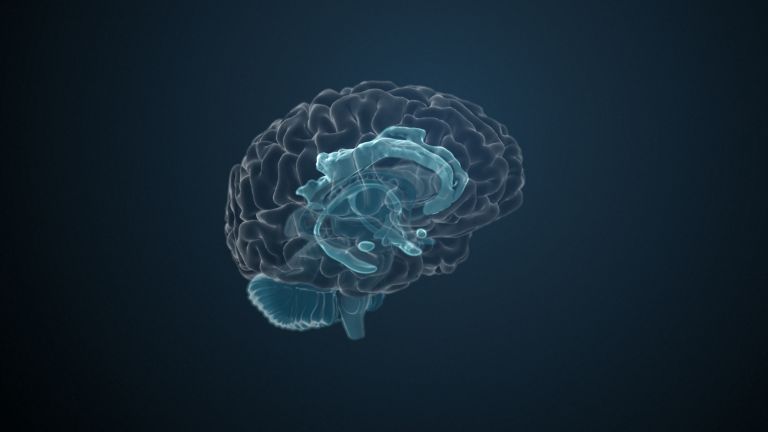

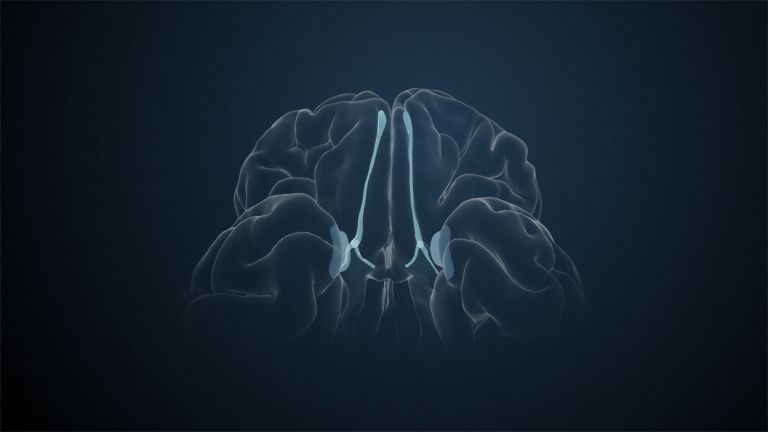

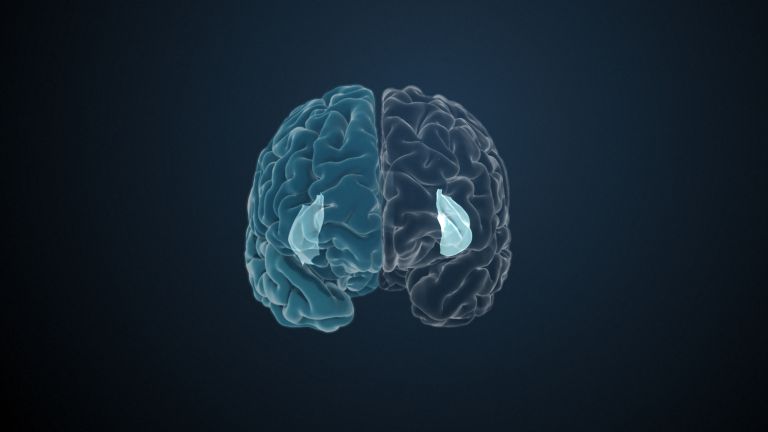

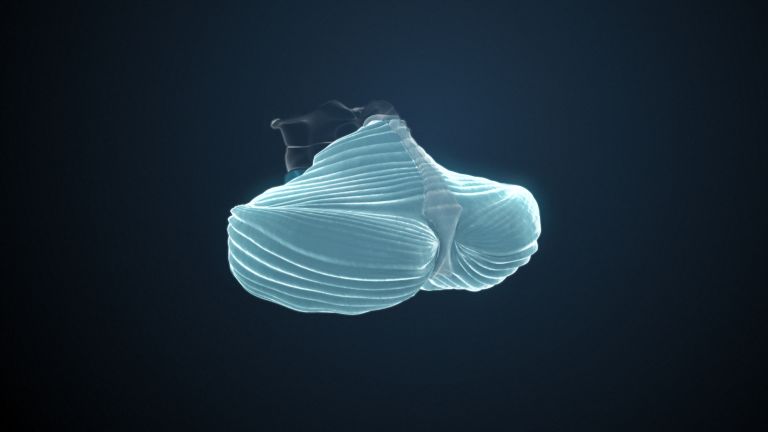

Cerebellar nuclei

Deep inside the Cerebellum lie the four paired Cerebellar nuclei They are the most important output stations of the cerebellum. Information is transmitted via them to other regions of the brain. Only a few fibers lead directly out of the cortex, such as to the balance system.

The names of these nuclei are vividly chosen. The dentate Nucleus is the largest. With its jagged profile, it resembles a gear wheel and is located furthest to the side.

Next to it is the emboliform nucleus, whose shape resembles a drop, and the two spherical globular nuclei. The emboliform and globose nuclei work closely together and are therefore often grouped together as the nucleus interpositus. Finally, the nucleus fastigii (summit nucleus) is located in the area of the vermis.

The nuclei are closely connected to motor centers in the brain stem, the thalamus, and, via the thalamus, the cerebral Cortex. The dentate nucleus, as part of the youngest part of the cerebellum – the pontocerebellum – plays a particularly key role: it mediates the precise coordination of voluntary movements and is involved in the planning of complex sequences of actions.

Cerebellum

Cerebellum

The cerebellum is an important part of the brain, located at the back of the brain stem and below the occipital lobe. It consists of two cerebellar hemispheres covered by the cerebellar cortex and plays an important role in motor processes, among other things. It develops from the rhombencephalon.

Cerebellar nuclei

A group of four paired nuclei located in the white matter of the cerebellum: the dentate nucleus, emboliform nucleus, globose nucleus, and fastigial nucleus. Functionally, the cerebellar nuclei are associated with motor tasks.

Nucleus

In cell biology, the nucleus in a cell is the cell nucleus, which contains the chromosomes, among other things. In neuroanatomy, the nucleus in the nervous system refers to a collection of cell bodies – known as gray matter in the central nervous system and ganglia in the peripheral nervous system.

Vermis

Cerebellar vermis

The vermis is an unpaired structure of the cerebellum located on the midline. It primarily receives somatosensory inputs.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

First published on August 23, 2011

Last updated on September 20, 2025