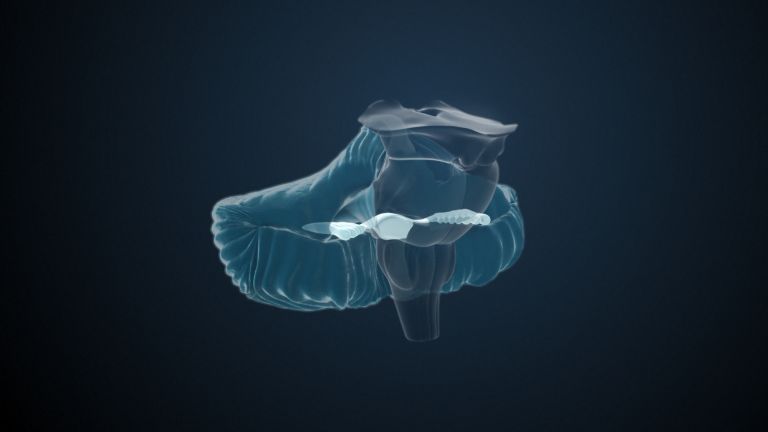

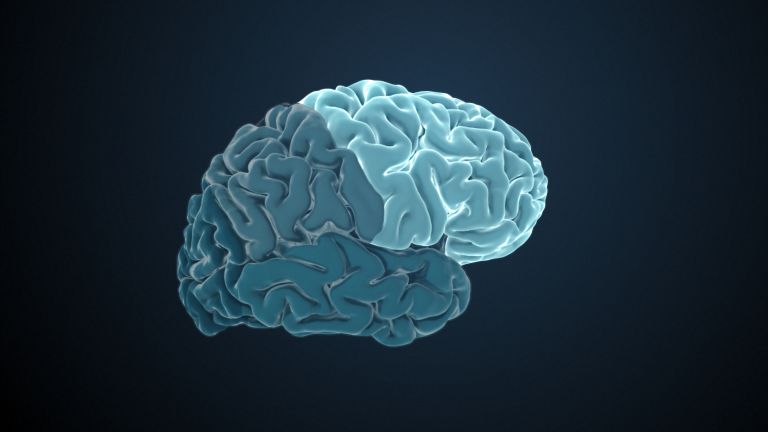

The Parietal Lobe

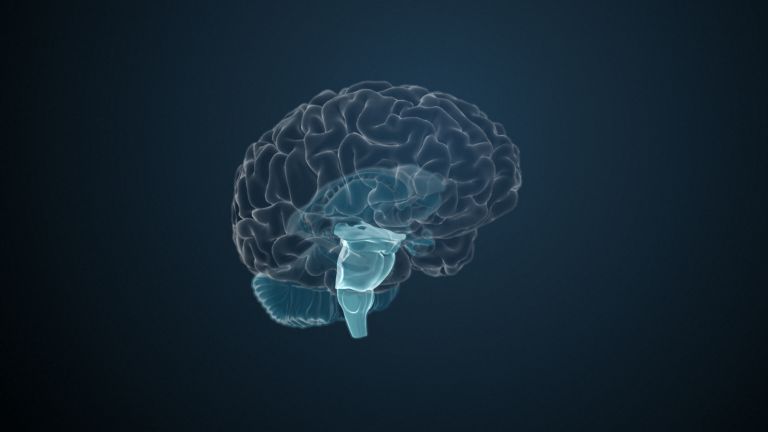

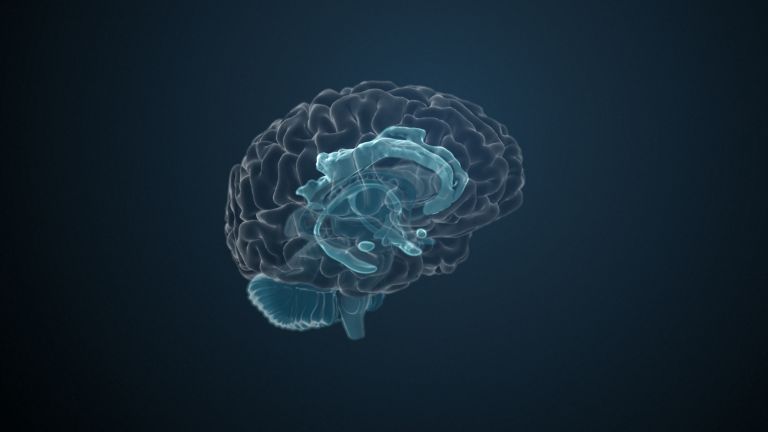

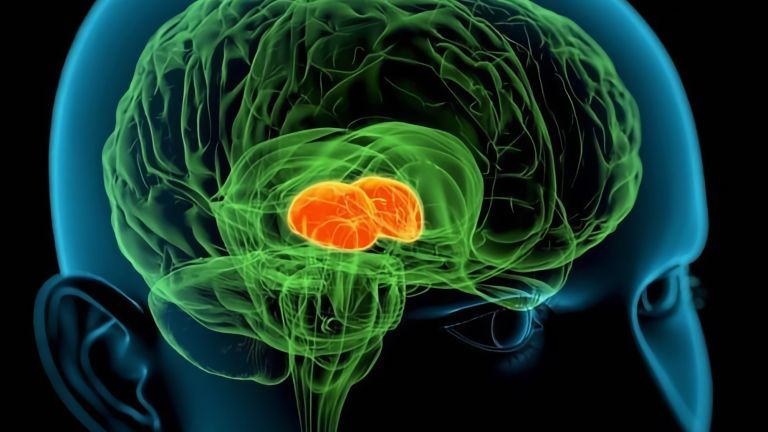

The parietal lobe is located behind the frontal lobe and is separated from it by the central sulcus. Two important nerve pathways that transmit bodily sensations such as pain, temperature, and touch end in the parietal lobe. However, the functions of the parietal lobe extend far beyond the body.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Herbert Schwegler, Prof. Dr. Anne Albrecht

Published: 18.09.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

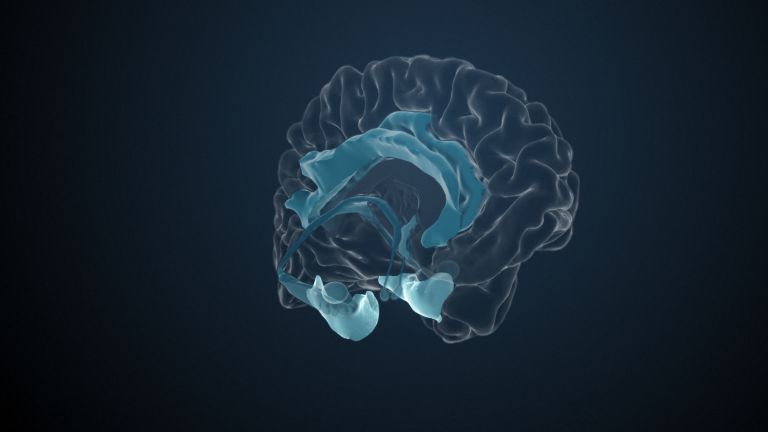

The main function of the parietal lobe is to process information from our somatosensory perception: what does the body feel (e.g., touch, pain, temperature), and where and in what position are our own limbs? While this takes place in the somatosensory cortex, the rear area of the parietal lobe relates this information to the near and distant environment. Damage to these areas can lead to what is known as neglect – to difficulties recognizing one's own limbs or one half of the environment.

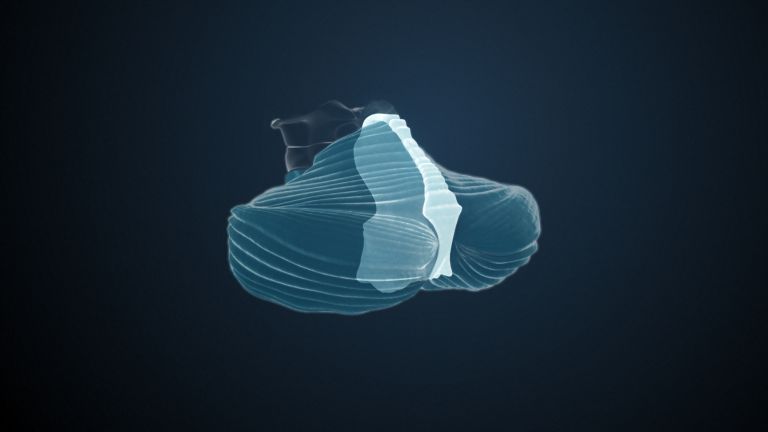

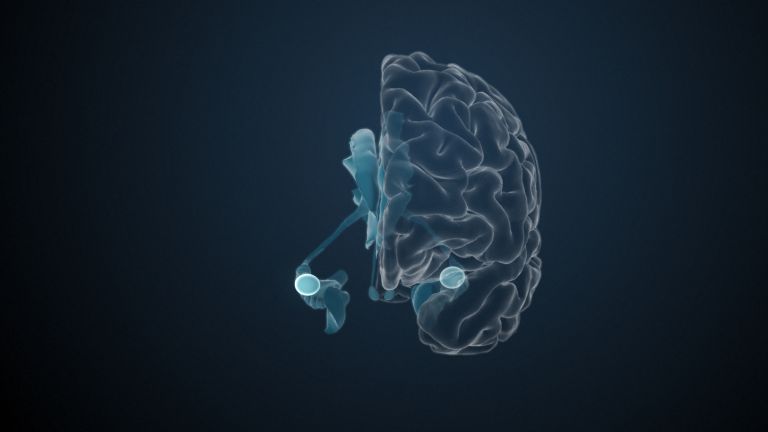

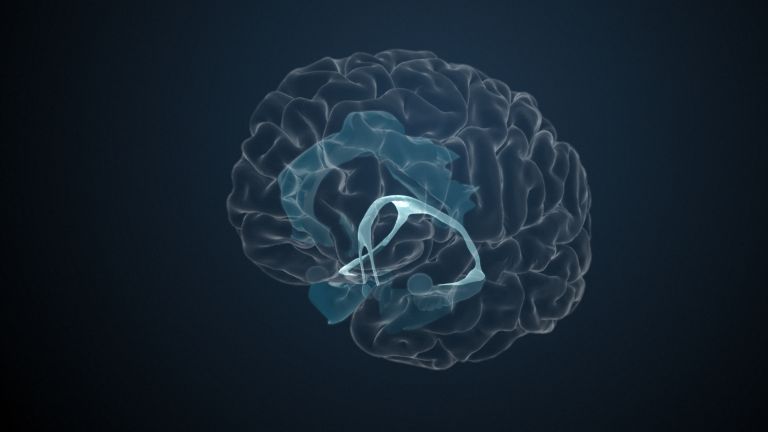

Strange things can happen at the junction between the temporal and parietal lobes, known as the temporoparietal junction (TPJ) – at least when this area is stimulated with electrodes. Olaf Blanke achieved this in Lausanne: he inserted an electrode directly at the end of the Sylvian fissure in the TPL of a young epilepsy patient. The stimulation caused the patient to feel a “shadow” behind her that mimicked all her actions but also had a will of its own – a kind of ghost. Interestingly, patients with damage in this region often report out-of-body experiences. Some even describe feeling as if they are floating above their own bodies and observing themselves from the outside.

Does this mean that there is a form of spirit or consciousness that can leave the body? Of course, science cannot completely rule this out, but the more likely explanation is that the TPL plays a crucial role in mediating the unity of body and mind by integrating bodily sensations and spatial awareness.

The perception of one's own body

Humans are natural dualists: even small children experience themselves – their minds – as separate from their bodies. This intuitive dualism was reinforced by René Descartes (1596−1650) at the beginning of the modern era with the observation that he could cut off his little finger and still be René Descartes. From today's perspective, however, the mind – or rather the brain – and the body form a unity. Nevertheless, the crucial question arises: How can the brain process all the different information from the body and the environment and integrate it into one coherent experience?

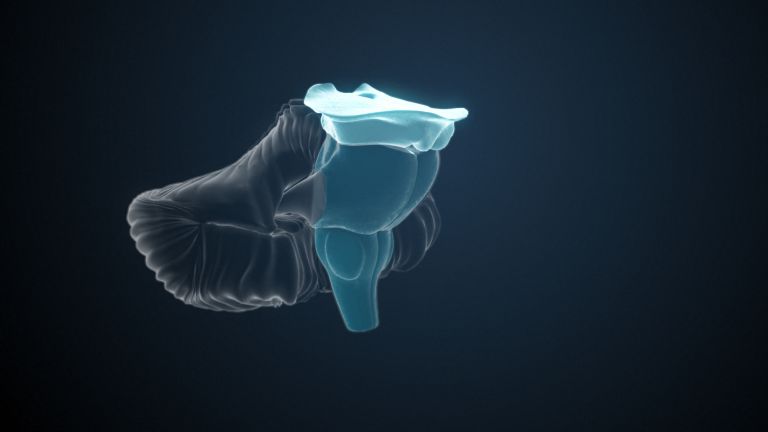

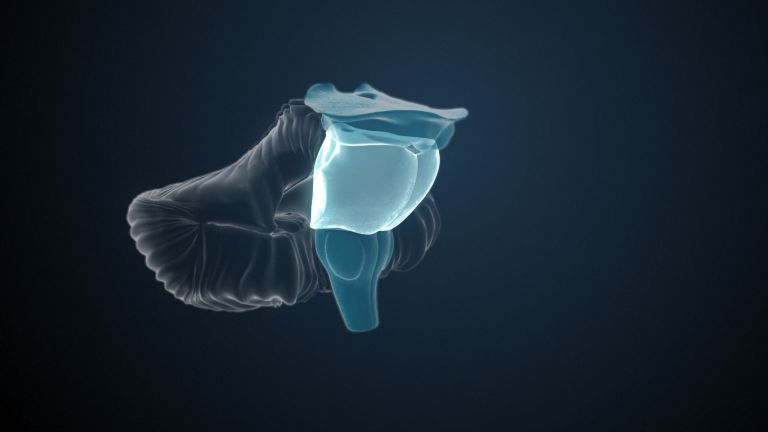

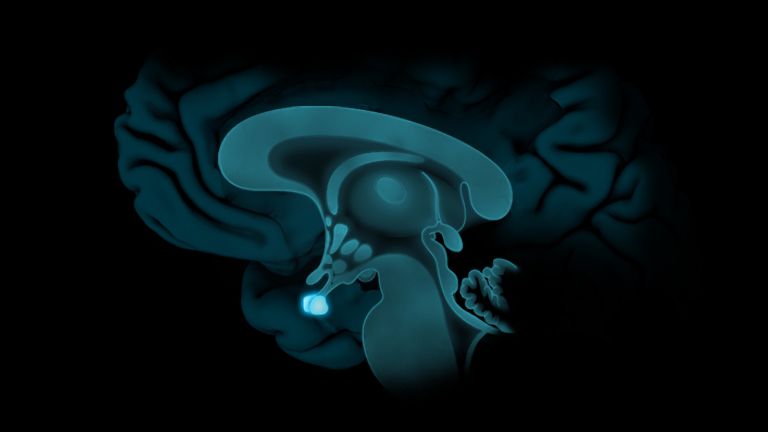

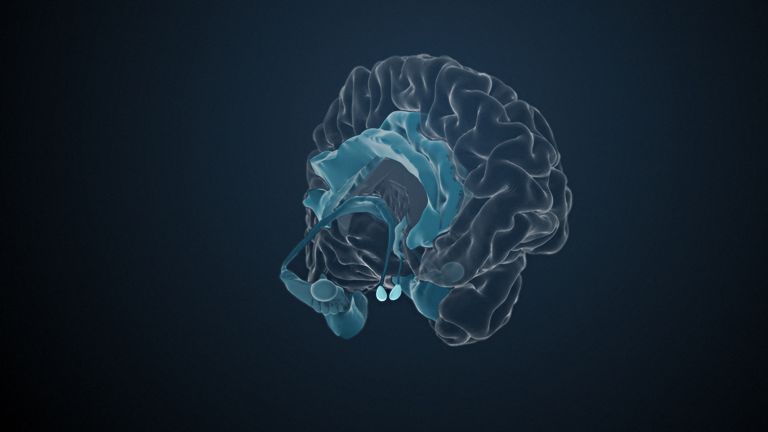

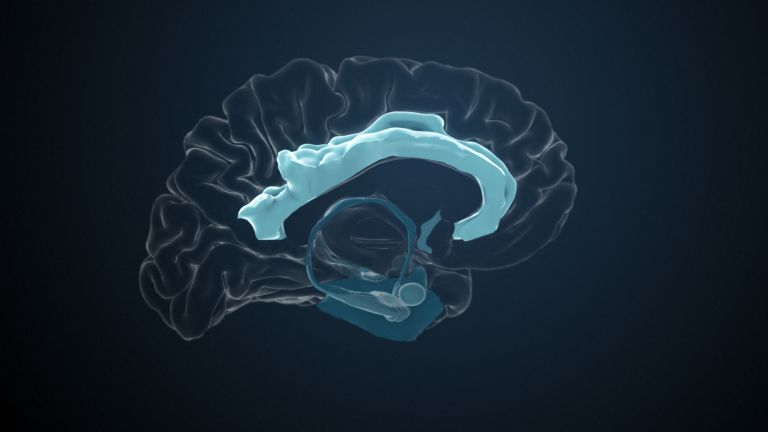

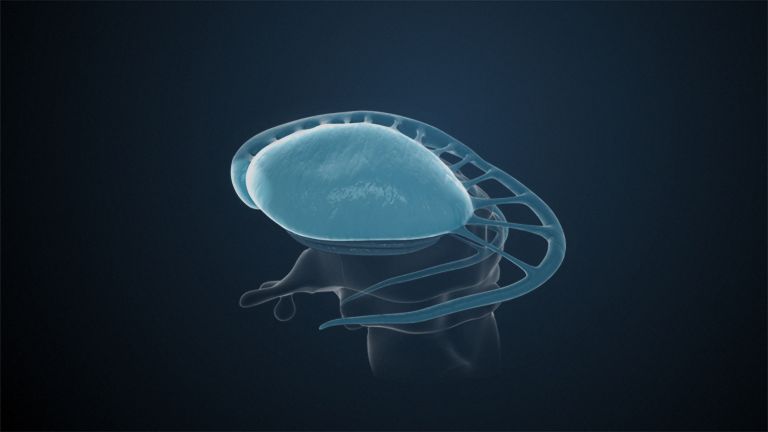

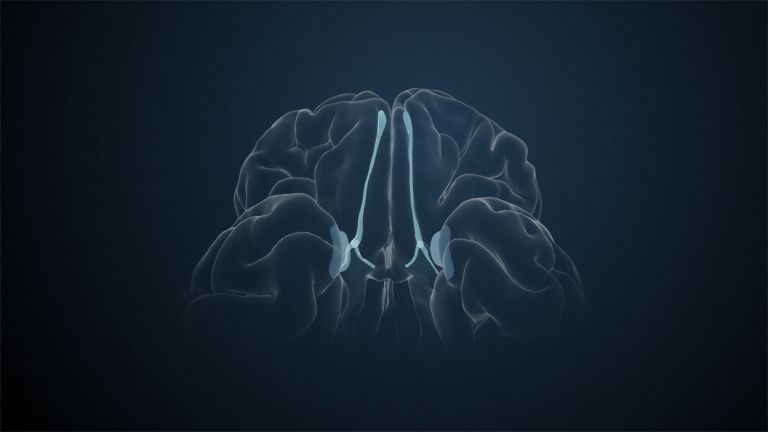

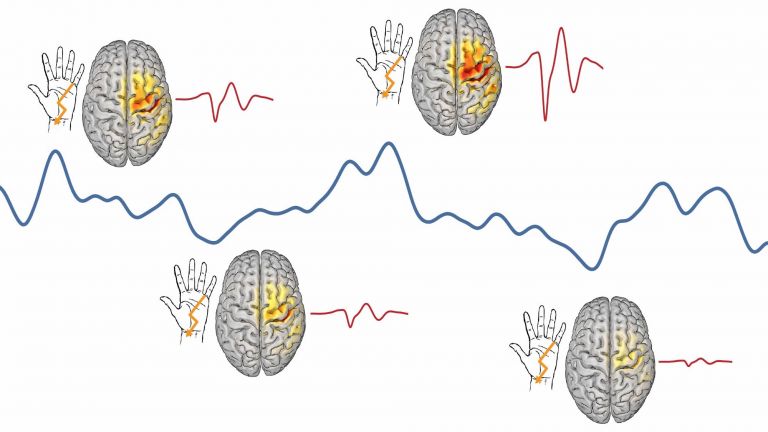

The skin has receptors for temperature and pain, touch and pressure sensations. Most of these signals reach the brain via the so-called protopathic pathway. The epicritic pathway provides finer tactile sensations, as well as information from the musculoskeletal system, i.e., about the activity of tendons and muscles – and thus about the position of individual body parts. This sense is called proprioception or self-perception. Both pathways run largely through the spinal cord and brain stem and cross over to the opposite side at different levels. Thus, the parietal lobe receives signals from the opposite, contralateral side of the body – the left parietal lobe receives information from the right side of the body and vice versa.

The primary somatosensory cortex and its functions

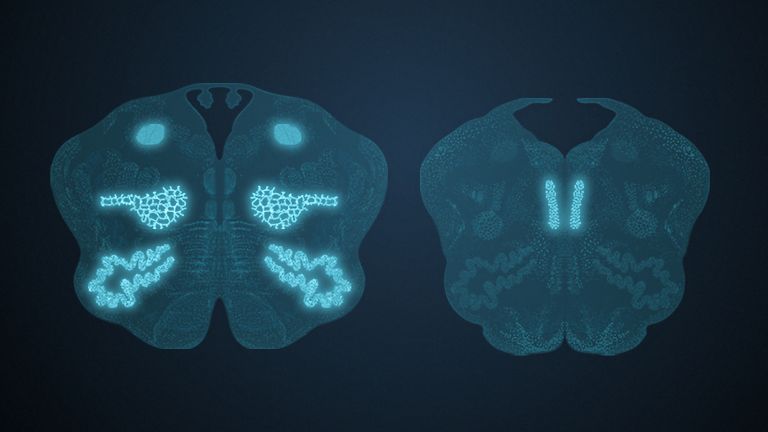

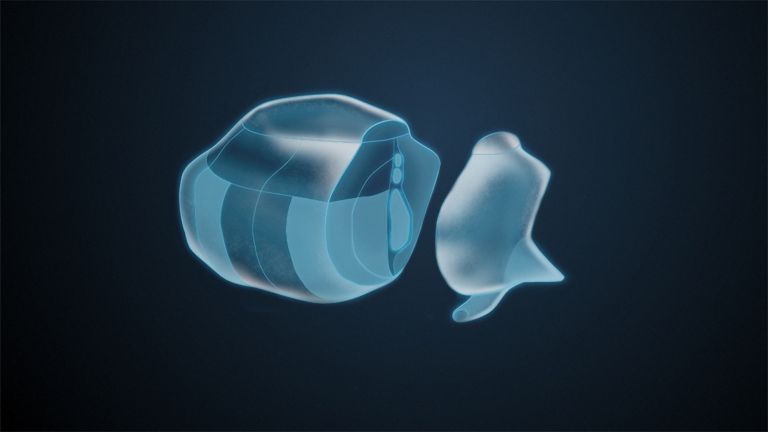

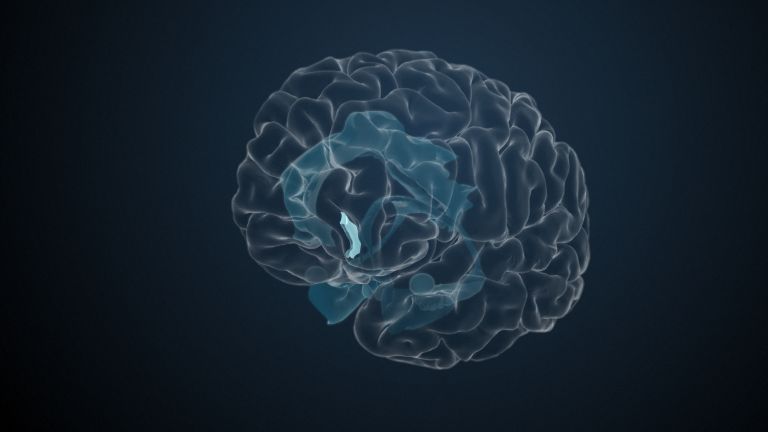

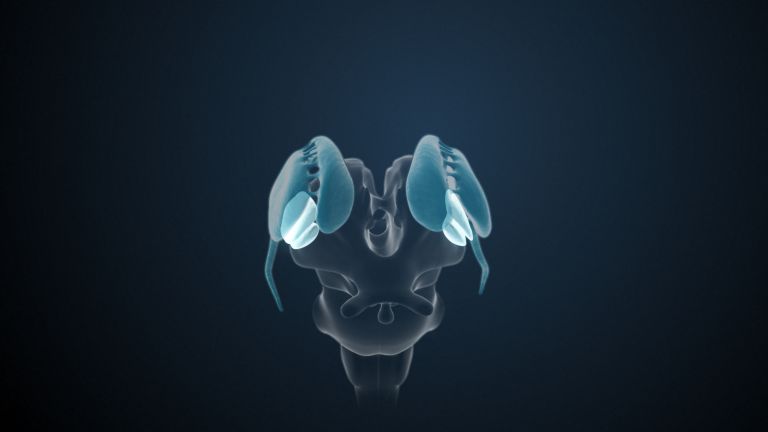

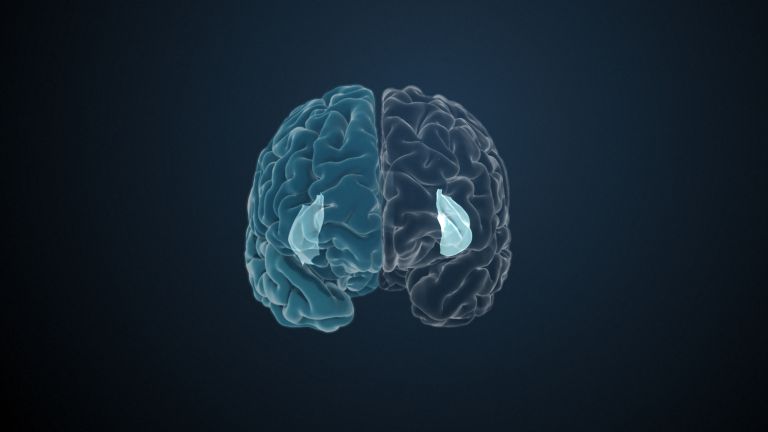

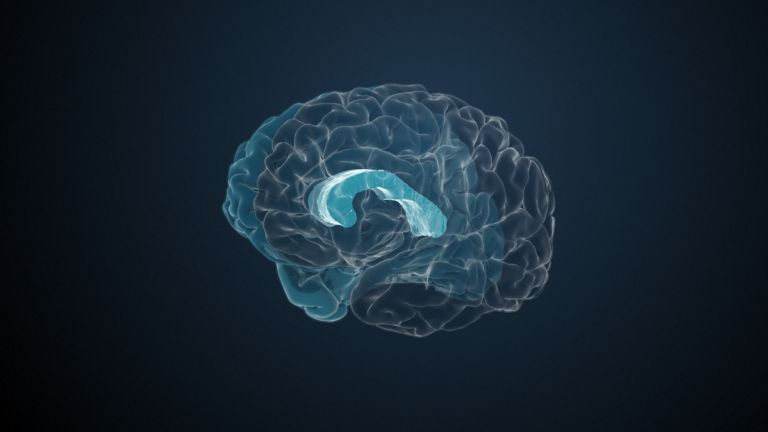

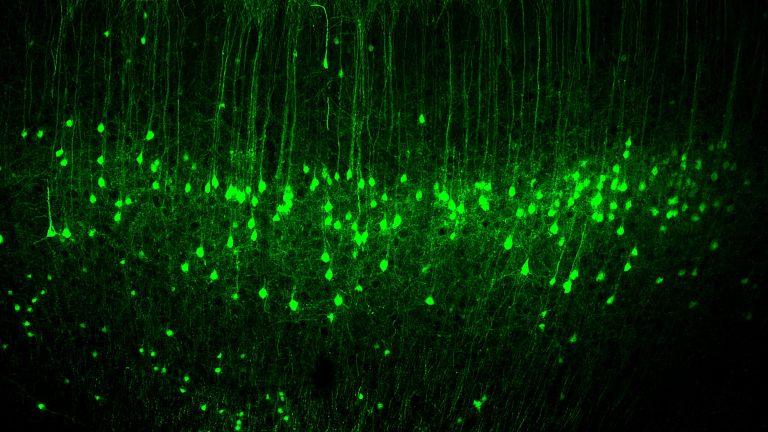

Two larger areas can be distinguished in the parietal lobe. The first is the primary somatosensory cortex in the postcentral gyrus – the direct projection site of the protopathic and epicritic pathways. As in the motor cortex, the somatotopic arrangement is preserved, resulting in a neural map of the body. The size of each area reflects the sensitivity of the corresponding structure: hand and head are represented very large, as the receptor density is particularly high there. The rest of the body is represented rather small.

Depending on their severity, lesions in the postcentral gyrus can lead to impaired sensation in the represented body part. This affects touch, pressure, and temperature. Unfortunately, pain sensation is the least affected.

Recommended articles

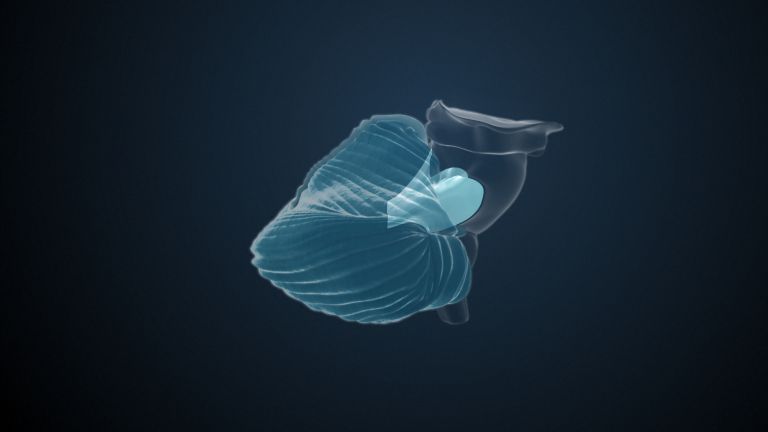

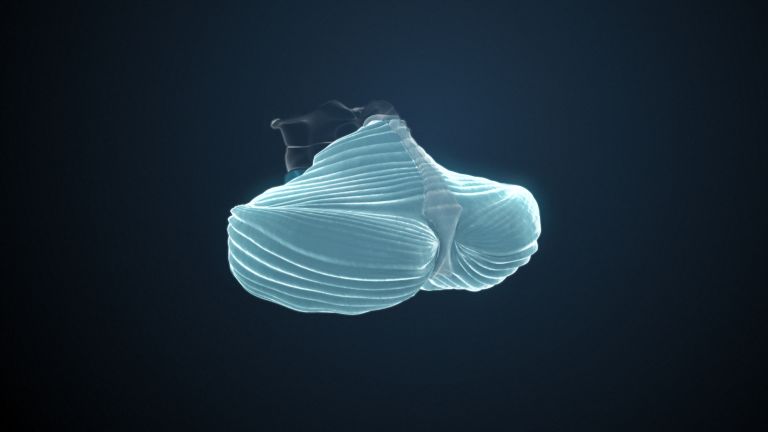

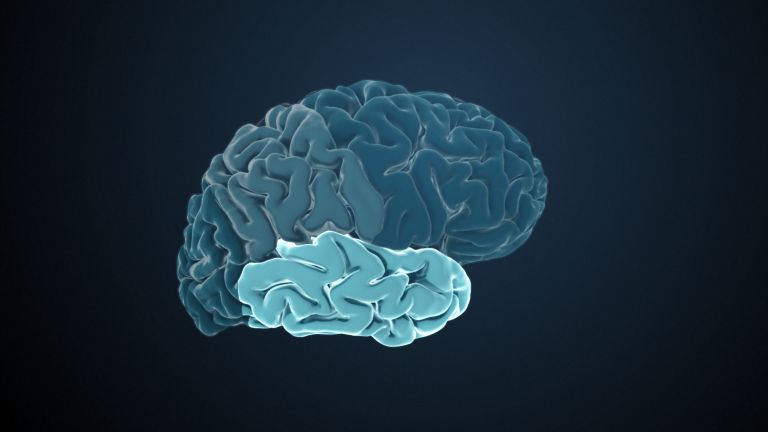

The posterior parietal cortex

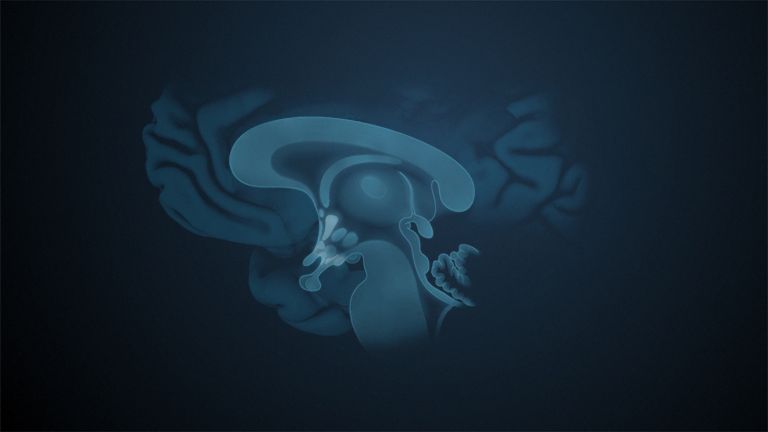

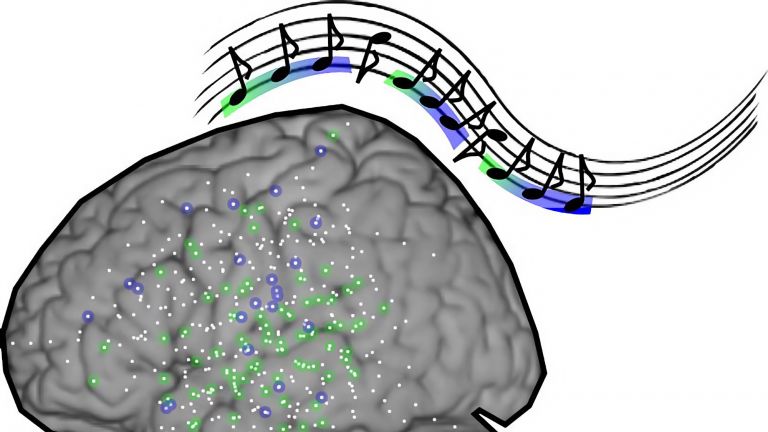

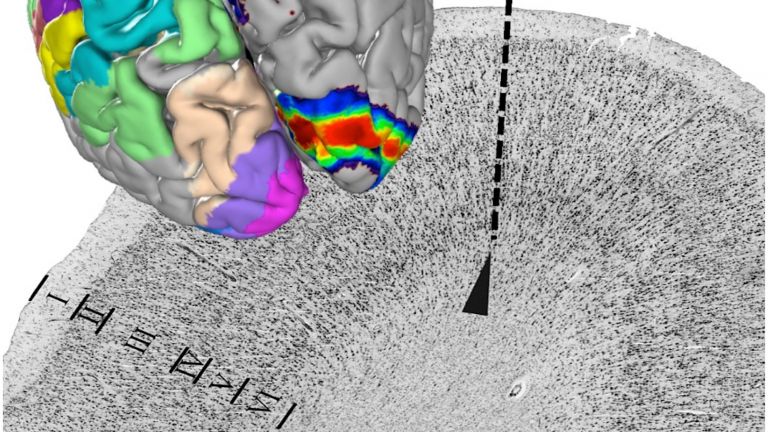

While proprioception, the spatial perception of one's own body, is the task of the primary somatosensory cortex, the posterior parietal cortex involves the environment. This is where proprioceptive, auditory, vestibular, and visual information is integrated. The combination of this information creates a three-dimensional image of the environment that is constantly updated. This helps the posterior parietal cortex to understand where we are in relation to our surroundings and how we can move around in a purposeful and precise manner.

This integration of perception sounds easier than it is: we talk to friends while offering them something to eat: “No thanks, no salad, but I'd like some more sauce...” Here, numerous movements – for example, those of the eyes – must be coordinated with auditory and visual inputs. All of this takes place in a room full of objects: salad bowls and cutlery, plates, and the large pepper mill that is always in the way. The brain is therefore required to create a coherent image of the body and the outside world, and this is decisively shaped by the association cortices of the posterior parietal cortex. One special feature concerns numbers – here, the intraparietal sulcus seems to play an important role.

Clinically, lesions of the posterior parietal lobe manifest themselves in a variety of ways – and have particular effects due to lateralization effects: if the right side is affected, this can lead to sometimes severe disturbances in orientation. The consequences of right-sided lesions of the lower parietal lobe are particularly striking – they can lead to what is known as left neglect: Those affected then no longer perceive large parts of the left visual field, for example, they only draw the right side of a clock, only eat what is on the right side of their plate, or even no longer perceive the entire left side of their body. In rare cases, patients even report finding a “foreign leg” in bed. Damage to the dominant hemisphere, which is usually the left hemisphere, can lead to apraxia: patients are no longer able to perform learned movements such as serving salad. Depending on the location and extent of the lesion, mathematical deficits may also occur, up to and including the loss of abstract thinking.

First published on September 9, 2011

Last updated on August 15, 2025