The Mesencephalon

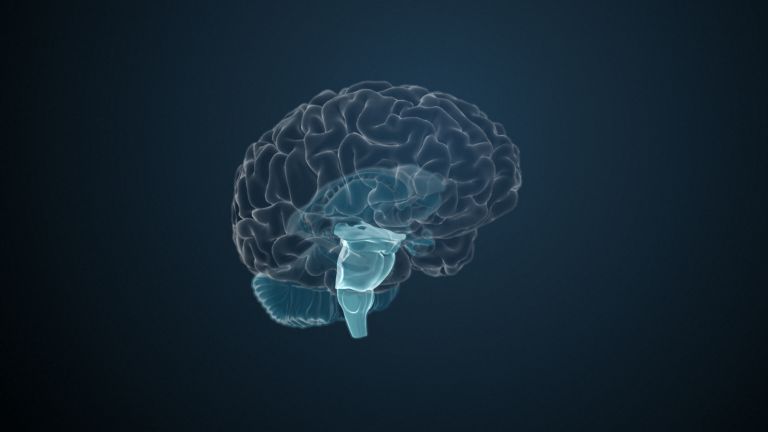

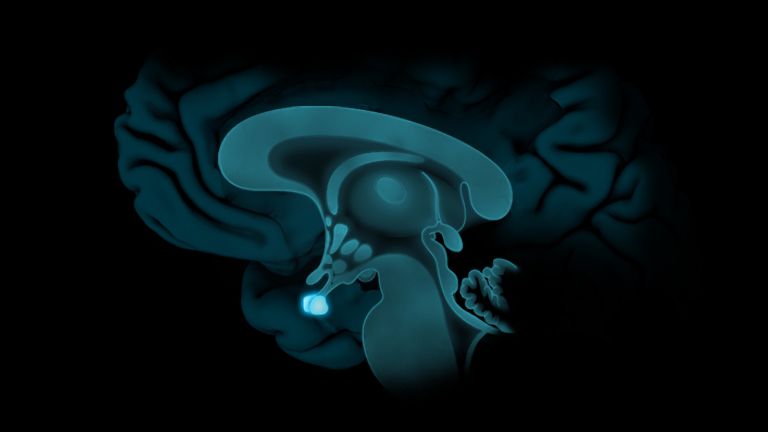

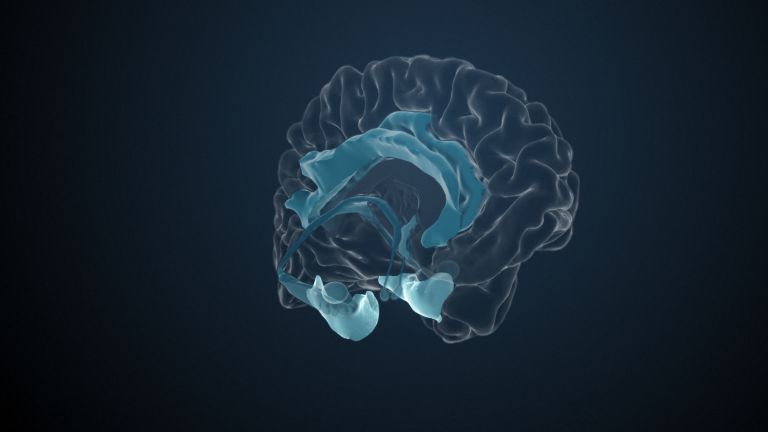

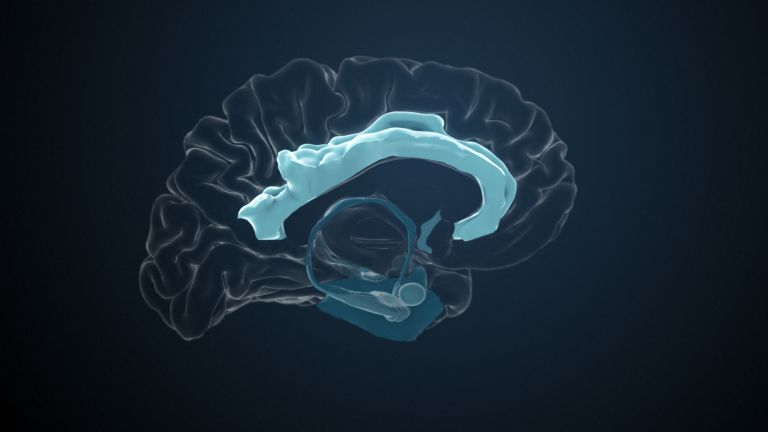

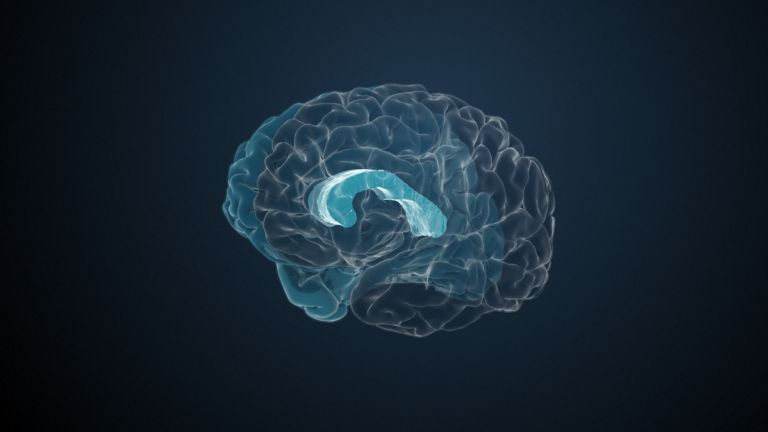

The mesencephalon – or midbrain – forms the uppermost section of the brain stem. Below it is the pons – the bridge – and above it are the structures of the diencephalon, or interbrain. Like the entire brain stem, the mesencephalon is also a central hub for motor function. Important control centers such as the substantia nigra and the nucleus ruber are located here. But there is also, four mounds for hearing and seeing, legs, and: The midbrain is the only structure in the brain that has its own water pipe, the aqueductus mesencephali. This is where the cerebrospinal fluid flows from the third to the fourth ventricle.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Hans-Dieter Hofmann, Prof. Dr. Andreas Vlachos

Published: 20.09.2025

Difficulty: serious

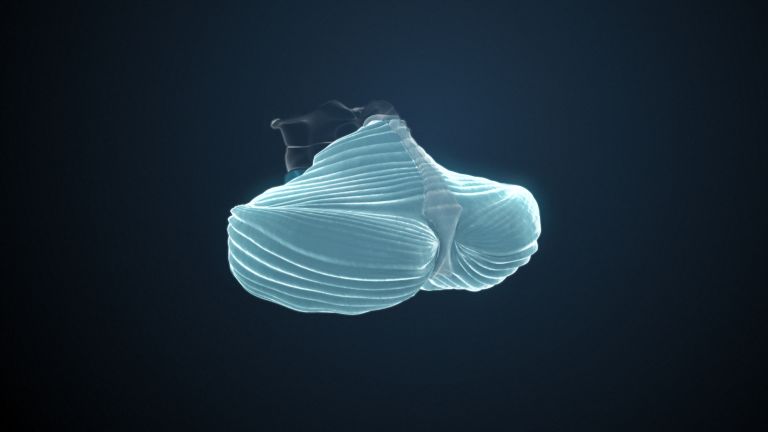

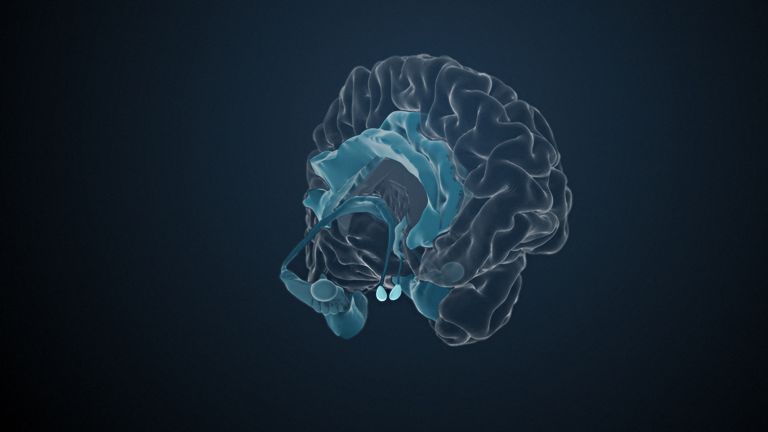

The Midbrain is divided into three areas: the cerebral peduncles (crura cerebri) at the front, the Tegmentum (Latin for covering) in the middle, and the tectum, the “roof” with the four mounds, at the back. It contains motor centers such as the Nucleus ruber and the substantia nigra, important parts of the midbrain reticular formation, and core areas for hearing, vision, pain regulation, and vegetative control. Emotional processes such as fear and stress reactions, as well as the regulation of mood and drive, are also co-controlled here.

Midbrain

mecencephalon

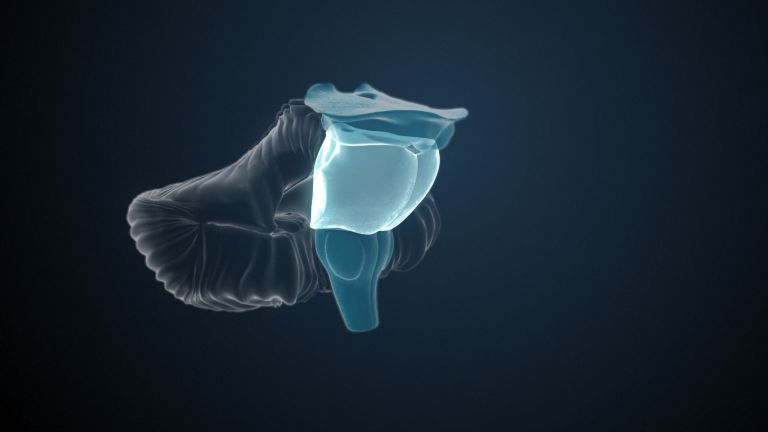

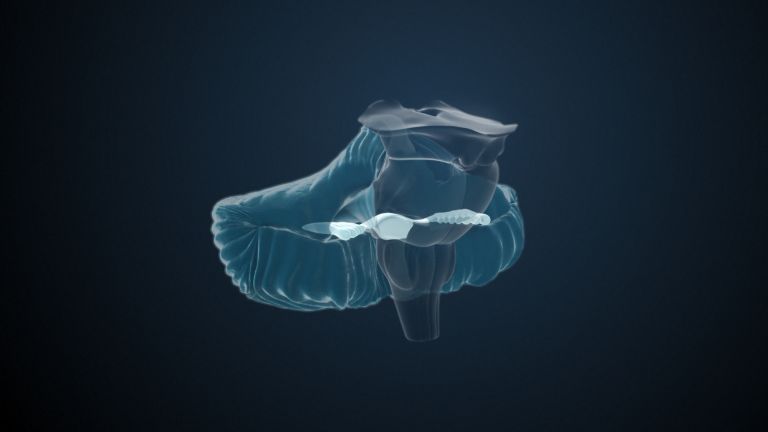

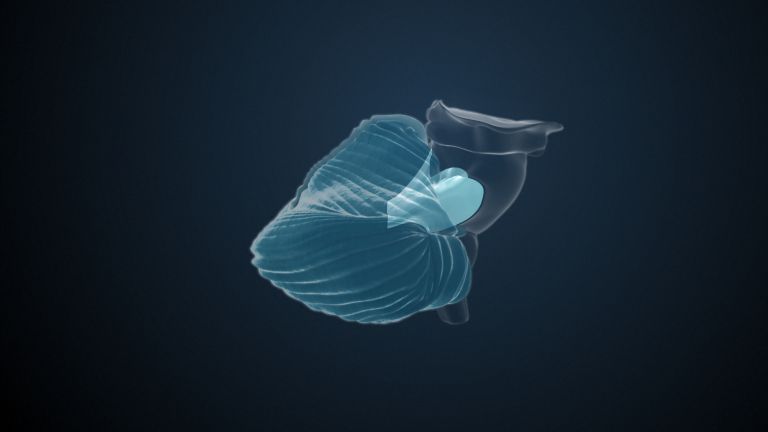

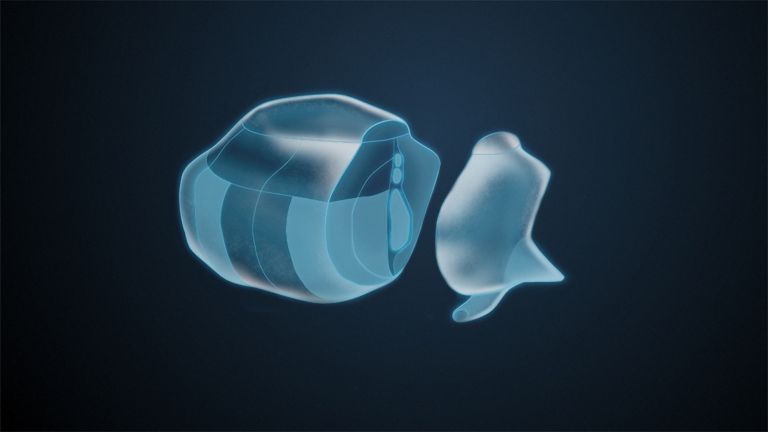

The midbrain is the uppermost section of the brain stem. Its regions are located around the aqueduct, a canal filled with cerebrospinal fluid. Prominent structures include the tectum, tegmentum, and substantia nigra.

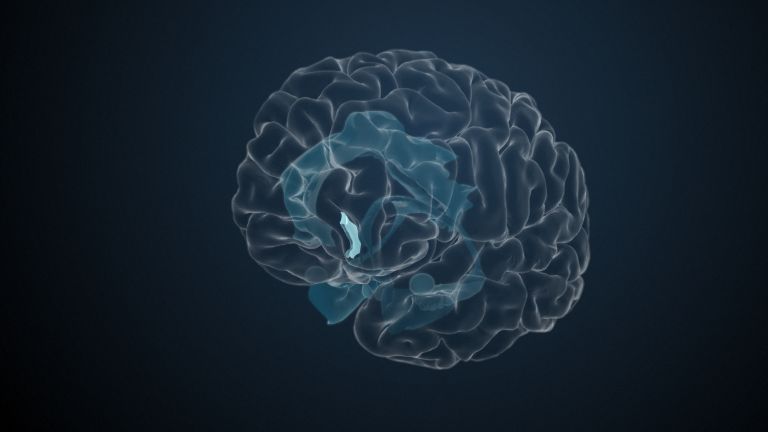

Tegmentum

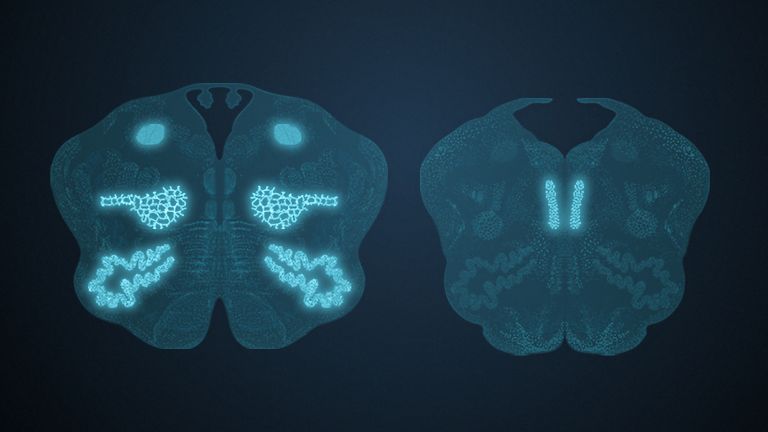

Tegmentum (from the Latin "tegere," meaning "to cover"). This is the ventral part of the midbrain located beneath the aqueduct. It contains nuclei such as the substantia nigra, the reticular formation, the cranial nerve nuclei, and the red nucleus.

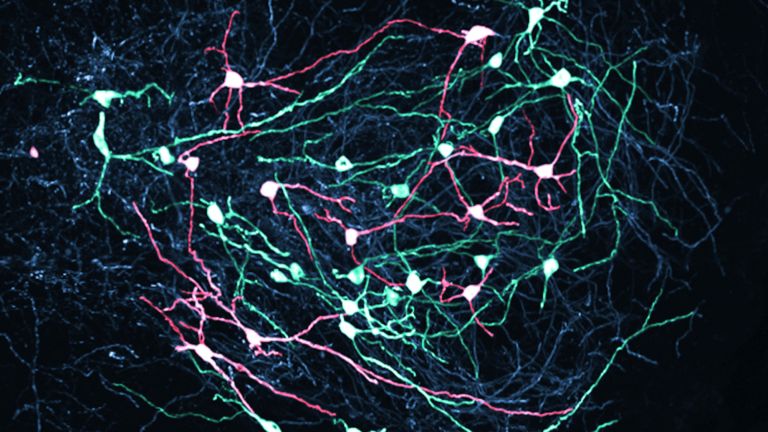

Nucleus

In cell biology, the nucleus in a cell is the cell nucleus, which contains the chromosomes, among other things. In neuroanatomy, the nucleus in the nervous system refers to a collection of cell bodies – known as gray matter in the central nervous system and ganglia in the peripheral nervous system.

External features

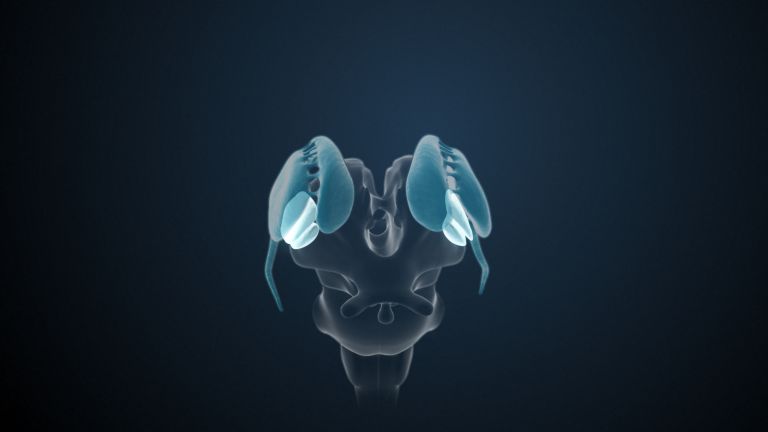

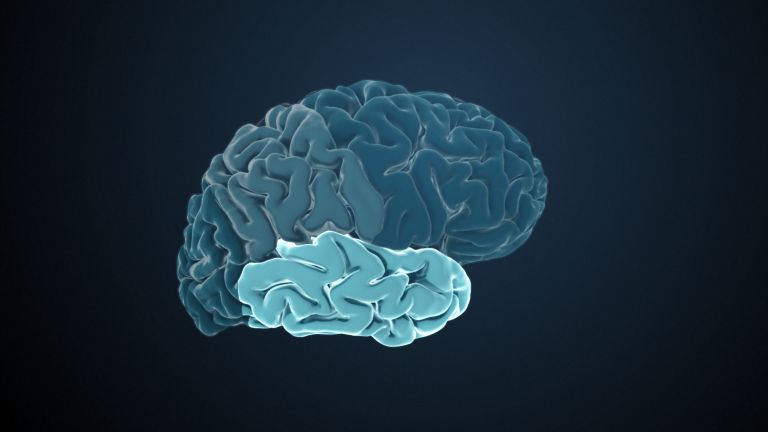

Viewed from the front, the Midbrain is dominated by the cerebral peduncles, the crura cerebri – large bundles of fibers that conduct signals from the Cortex to the Spinal cord and to the Pons and Cranial nerve nuclei. Descending pathways from almost all parts of the cerebral cortex run neatly through them: on the inside, mainly fibers from the frontal lobe; on the outside, those from the parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes; and in the middle, the pyramidal tract, which controls voluntary motor function. The head and face are represented more on the inside, the legs and feet on the outside – like a small “homunculus”.

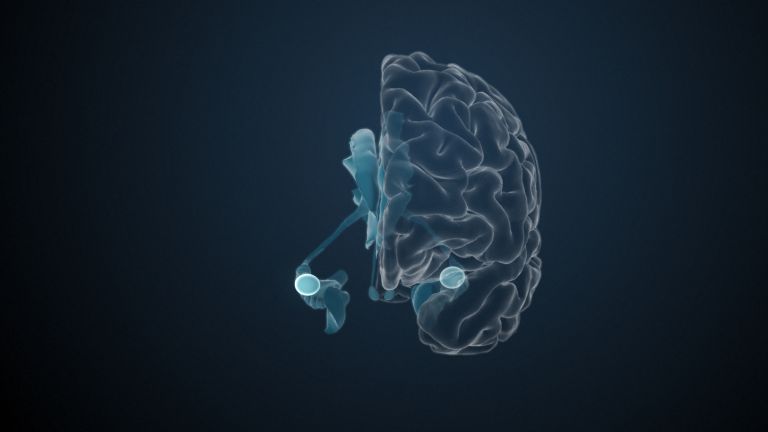

From behind, two pairs of mounds can be seen, collectively known as Tectum (or lamina tecti, or lamina quadrigema). The upper mounds, the colliculi superiores, receive direct inputs from the Retina of the Eye via the Optic nerve and visual tract. This primarily involves information about rapidly changing stimuli – i.e., movement. This could be a moving car that we follow with our eyes, or a branch that is about to hit our face, causing us to reflexively close our eyes to protect them. Saccades – the rapid eye movements that you are making right now, for example, while reading these words – are also prepared here, with the colliculi selecting the next fixation targets. The actual eye movements then occur in a network that extends from the frontal visual area of the cerebral cortex to the gaze centers in the pons (horizontal saccades) and midbrain (vertical saccades) to the oculomotor nuclei.

Looking at the midbrain from the front, we see the third cranial nerve, the oculomotor nerve, emerging between the cerebral peduncles. The deficits associated with damage to the upper colliculi are correspondingly similar: it is no longer possible to follow an object with the eyes, although all visual stimuli continue to be perceived and processed.

The inferior colliculi, the lower mounds, serve as a switching point for most of the fibers of the Auditory pathway The signals run from here directly to the Medial geniculate body of the thalamus and from there on to the Primary auditory cortex This central location of the inferior colliculi in the auditory pathway means that damage to them can lead to reduced hearing ability. Since the inferior colliculi also send signals to the superior colliculi – and vice versa – this enables the reflexive integration of both sensory modalities. And we automatically look in the direction of a loud noise.

The trochlear nerve (IV) is the only cranial nerve that exits at the back of the brainstem – directly below the inferior colliculi.

Midbrain

mecencephalon

The midbrain is the uppermost section of the brain stem. Its regions are located around the aqueduct, a canal filled with cerebrospinal fluid. Prominent structures include the tectum, tegmentum, and substantia nigra.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Spinal cord

medulla spinalis

The spinal cord is the part of the central nervous system located in the spine. It contains both the white matter of the nerve fibers and the gray matter of the cell nuclei. Simple reflexes such as the knee-jerk reflex are already processed here, as sensory and motor neurons are directly connected. The spinal cord is divided into the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral spinal cord.

Pons

pons

Area in the brain stem between the medulla oblongata and the mesencephalon. It acts as a switching station for many nerve pathways between the brain and spinal cord and contains numerous nuclei, including cranial nerves and those involved in controlling motor function in cooperation with the cerebellum.

cranial

A positional term – cranial means "towards the head." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction along the neural axis, i.e., forward.

In animals (without upright gait), the designation is simpler, as it always means forward. Due to the upright gait of humans, the brain bends in relation to the spinal cord, where cranial also means "upward."

Cranial nerve

A group of 12 pairs of nerves that originate directly in the brain, mostly in the brain stem. They are numbered with Roman numerals (I–XII). Unlike the rest, the first and second cranial nerves (olfactory and optic nerves) are not part of the peripheral nervous system, but rather the central nervous system.

frontal

An anatomical position designation – frontal means "towards the forehead," i.e., at the front.

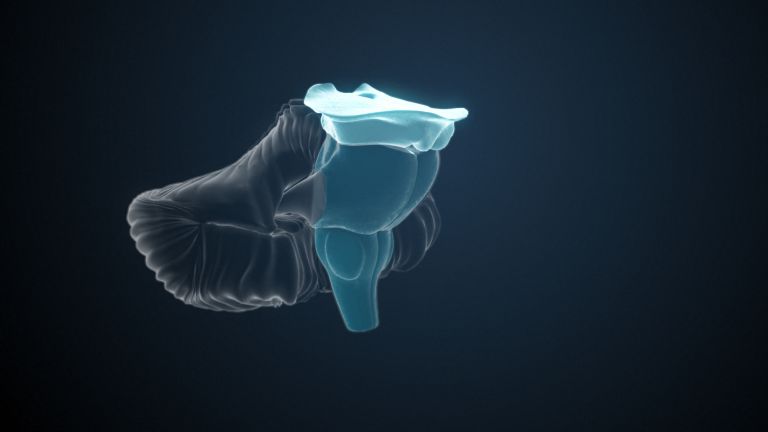

Tectum

A structure in the midbrain consisting of two pairs of mounds, the upper colliculi and the lower colliculi.

Retina

The retina is the inner layer of the eye covered with pigment epithelium. The retina is characterized by an inverse (reversed) arrangement: light must first pass through several layers before it hits the photoreceptors (cones and rods). The signals from the photoreceptors are transmitted via the optic nerve to the processing areas of the brain. The reason for the inverse arrangement is the evolutionary development of the retina, which is a protrusion of the brain.

The retina is approximately 0.2 to 0.5 mm thick.

Eye

bulbus oculi

The eye is the sensory organ responsible for perceiving light stimuli – electromagnetic radiation within a specific frequency range. The light visible to humans lies in the range between 380 and 780 nanometers.

Optic nerve

nervus opticus

The axons (long fiber-like extensions) of the retinal ganglion cells form the optic nerve, which leaves the eye at the back of the optic disc. It comprises approximately one million axons and has a diameter of approximately seven millimeters.

inferior

An anatomical position designation – inferior means located further down, the lower part.

Auditory pathway

The auditory pathway refers to the nerve fibers that transmit acoustic information from the inner ear to the primary auditory cortex. In humans, the auditory pathway consists of five switching points: the spiral ganglion, the auditory nuclei in the brainstem, the inferior colliculus, the medial geniculate body of the thalamus, and the primary auditory cortex.

medial

A positional term – medial means "towards the middle." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction toward the body, away from the sides.

Medial geniculate body

corpus geniculatum medialis

The medial geniculate body (medial geniculate nucleus) is a nucleus of the thalamus (the largest part of the diencephalon). As the central switching point of the auditory pathway, it transmits impulses from the inferior colliculus to the auditory radiation. Together with the lateral geniculate body, it forms the metathalamus.

Primary auditory cortex

The first processing station in the cerebral cortex for auditory information. The primary auditory cortex is located in the Heschl's gyrus and receives inputs from the medial geniculate nucleus of the thalamus. It is organized tonotopically – its neurons are arranged continuously according to frequency.

Recommended articles

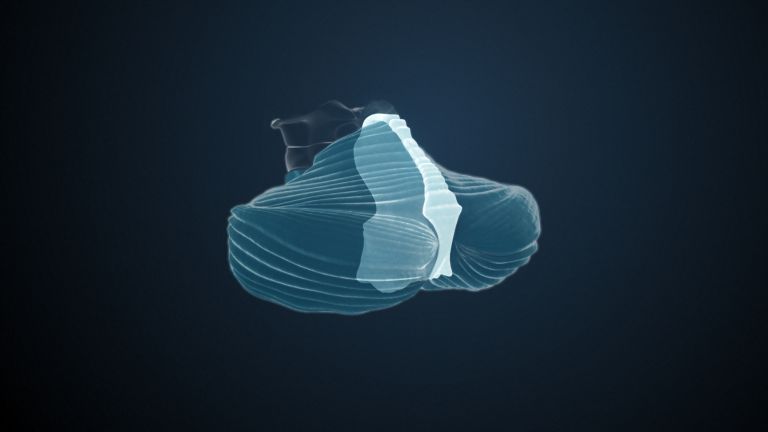

Inner qualities

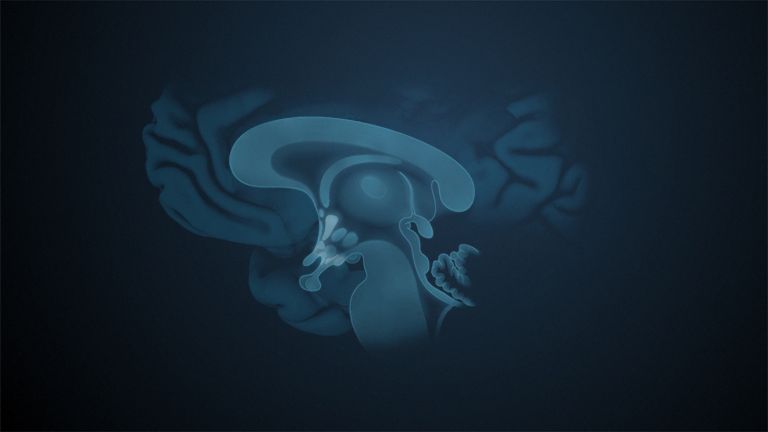

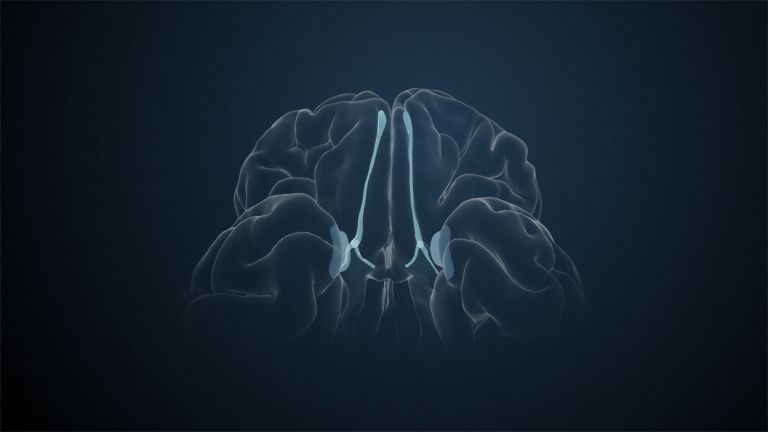

The cerebral peduncles at the front and the four mounds at the back are two of the three layers into which the Midbrain is divided. Between these two lies the tegmentum, which contains numerous important nuclei and core areas. Once again, vision is functionally part of this: the oculomotor nuclei, the oculomotor nerve (III) and the trochlear nerve (IV). They control six muscles per eye, which requires very complex interconnection. While vertical Eye movements are controlled by the midbrain, horizontal movements are primarily triggered in the Pons. Closely related to this is the Edinger-Westphal nucleus, which contains parasympathetic fibers for the Pupil response. The pupillary light reflex runs afferently via the Optic nerve (nervus opticus, II) and the thalamus, while the efferent control of the pupil muscles is via the oculomotor nerve (III).

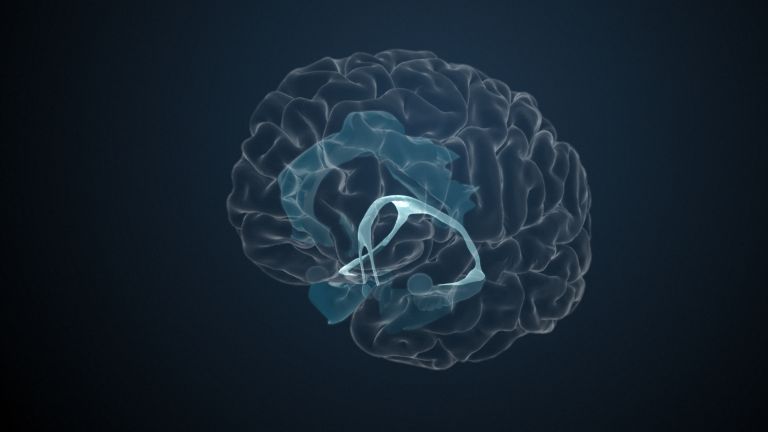

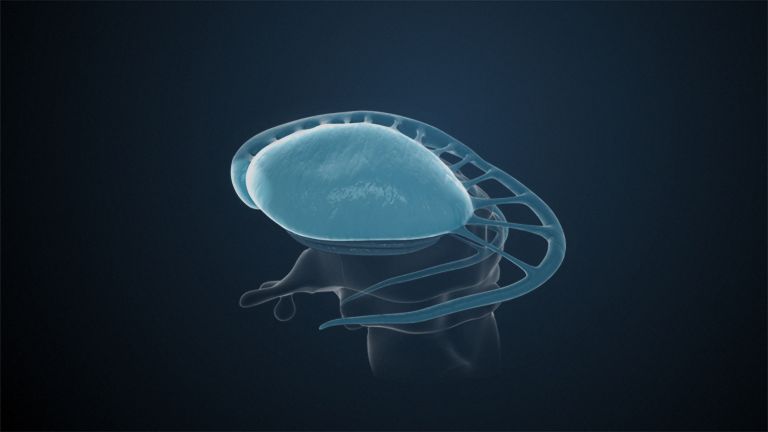

But there are also structures beyond vision. One example is the substantia grisea periaqueductalis, or Periaqueductal gray matter. It gets its name because the aqueduct, the aqueductus mesencephali, flows directly through this Gray matter It is a central hub for the suppression of pain and becomes active primarily in dangerous situations: pain is then “blocked out” so that escape or defense reactions remain possible.

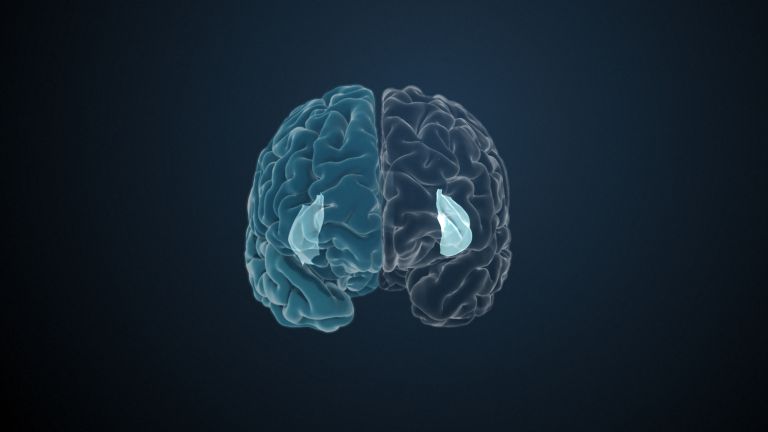

Another important Nucleus in the midbrain is the red nucleus, or Nucleus ruber. It owes its red color to its high iron content. The nucleus ruber belongs to the extrapyramidal motor system, meaning it performs motor tasks that are not negotiated via the pyramidal tract. It is part of a neural loop between the olive and the Cerebellum. In the past, its failure was directly equated with what is known as intention tremor – a tremor that becomes stronger the closer a movement gets to its target. Today, we know that lesions in this area tend to lead to a more complex picture: The Holmes tremor, which combines elements of resting, holding, and intention tremor. This illustrates the close cooperation between the midbrain and cerebellum in controlling movement.

The locus coeruleus – the blue spot – owes its dark bluish color to the pigments in its cells. These produce norepinephrine, a stress hormone, which is why, despite its beautiful name, the locus coeruleus is not only considered an arousal system – in connection with the Reticular formation (RF) – but also an alarm system. And as we know, too much alarm, too much stress, and too much noradrenaline do not have a positive effect on physical and mental health.

The Neurotransmitter serotonin, on the other hand, has little to do with stress. On the contrary, it is involved in falling asleep and maintaining a delicate balance of emotional equilibrium. And it is indeed a balance, because too much Serotonin is just as harmful as too little. The only location of serotonin production in the brain is the raphe nuclei, which form the innermost area of the reticular formation. From here, they release their valuable cargo into large parts of the brain, especially the limbic system.

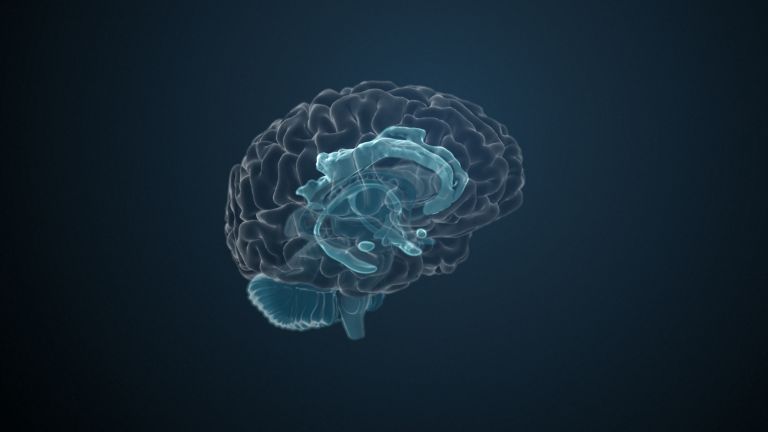

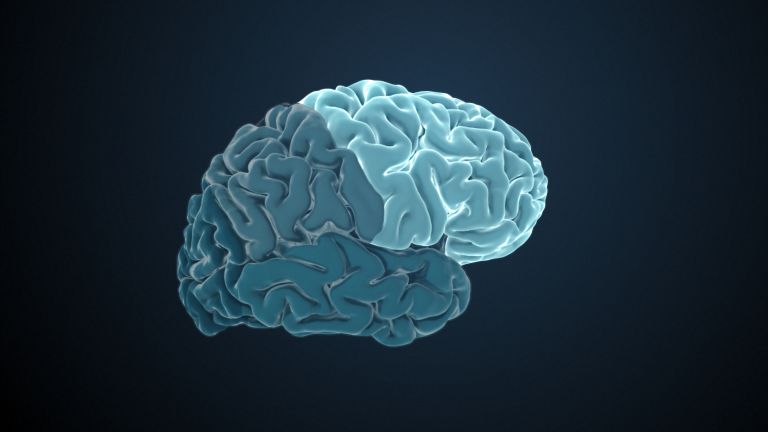

At the top of the midbrain, the substantia nigra, or black substance, is located. It owes its name to a high melanin content in the cell nuclei. And its fame to Parkinson's disease since it sits in the middle of a network of systems that connect and coordinate movements, its failure has fatal consequences for the initiation of movement and the basic drive to move. The neurotransmitter of the Substantia nigra is Dopamine – and it is these dopaminergic neurons that die in Parkinson's disease. Up to 70 percent of these cells can die before symptoms become apparent.

The reticular formation runs through the entire Brain stem – an entire network of interconnected nuclei that have many different tasks. We have already mentioned the arousal center – more precisely, the ascending reticular activating system (ARAS) –which increases activity in the thalamus and cortex, ensuring not only wakefulness but also consciousness. Damage to this area can lead to coma, although other parts of the reticular formation responsible for respiration and circulatory functions keep the organism alive.

Midbrain

mecencephalon

The midbrain is the uppermost section of the brain stem. Its regions are located around the aqueduct, a canal filled with cerebrospinal fluid. Prominent structures include the tectum, tegmentum, and substantia nigra.

Eye

bulbus oculi

The eye is the sensory organ responsible for perceiving light stimuli – electromagnetic radiation within a specific frequency range. The light visible to humans lies in the range between 380 and 780 nanometers.

Pons

pons

Area in the brain stem between the medulla oblongata and the mesencephalon. It acts as a switching station for many nerve pathways between the brain and spinal cord and contains numerous nuclei, including cranial nerves and those involved in controlling motor function in cooperation with the cerebellum.

Pupil

The opening in the eye through which light enters. The size of the pupil is determined by the iris and changes reflexively (pupillary reflex). This process of adjusting to the brightness of the environment is called adaptation.

Optic nerve

nervus opticus

The axons (long fiber-like extensions) of the retinal ganglion cells form the optic nerve, which leaves the eye at the back of the optic disc. It comprises approximately one million axons and has a diameter of approximately seven millimeters.

Periaqueductal gray

Substania grisea periaquaeductalis

A core area in the brain stem that is involved in defensive behavior and fear and flight reflexes via close connections to the limbic system. It also plays an important role in pain suppression by regulating signals from the spinal cord to the brain. It is considered an endogenous pain control system and is an important target for medication.

Gray matter

Grey matter refers to a collection of nerve cell bodies, such as those found in nuclei or in the cortex.

Nucleus

In cell biology, the nucleus in a cell is the cell nucleus, which contains the chromosomes, among other things. In neuroanatomy, the nucleus in the nervous system refers to a collection of cell bodies – known as gray matter in the central nervous system and ganglia in the peripheral nervous system.

Cerebellum

Cerebellum

The cerebellum is an important part of the brain, located at the back of the brain stem and below the occipital lobe. It consists of two cerebellar hemispheres covered by the cerebellar cortex and plays an important role in motor processes, among other things. It develops from the rhombencephalon.

Reticular formation

formatio reticularis

The reticular formation is a network of numerous nuclei in the brain stem. It has a variety of tasks, for example, it is responsible for alertness, the integration of motor, sensory, and vegetative processes, and the sleep-wake cycle.

Neurotransmitter

A neurotransmitter is a chemical messenger, an intermediary substance. It is released by the sender neuron at the sites of cell-cell communication and has an excitatory or inhibitory effect on the receiver neuron.

Serotonin

A neurotransmitter that acts as a messenger in the transmission of information between neurons at their synapses. It is primarily produced in the raphe nuclei of the brain stem and plays a key role in sleep and alertness, as well as emotional well-being.

Parkinson's disease

Morbus Parkinson

Parkinson's disease is one of the most common neurological disorders, caused by the death of dopamine-producing neurons in the substantia nigra, leading to a neurotransmitter imbalance in the basal ganglia. Symptoms usually begin late in life with mild tremors (resting tremor), increasing stiffness of the limbs, and slowed voluntary movements (bradykinesia). Later, postural instability, balance disorders, and difficulty walking occur. Other typical features include rigid facial expressions (hypomimia), a shuffling gait, and muscle stiffness (rigor). The disease is incurable, but its symptoms can be treated with medication (e.g., L-dopa, dopamine agonists) or surgery involving deep brain stimulation (brain pacemaker).

Substantia nigra

A nucleus complex in the ventral mesencephalon that plays a central role in initiating and modulating movement. It appears dark due to neuromelanin. Its dopaminergic neurons project via the nigrostriatal pathways to the putamen and caudate nucleus. Failure of these neurons leads to the typical symptoms of Parkinson's disease.

Dopamine

Dopamine is an important neurotransmitter in the central nervous system that belongs to the catecholamine group. It plays a role in motor function, motivation, emotion, and cognitive processes. Disruptions in the function of this transmitter play a role in many brain disorders, such as schizophrenia, depression, Parkinson's disease, and substance dependence.

Brain stem

truncus cerebri

The "trunk" of the brain, to which all other brain structures are "attached," so to speak. From bottom to top, it comprises the medulla oblongata, the pons, and the mesencephalon. It transitions into the spinal cord below. It is a center for vital functions such as breathing and heartbeat and contains ascending and descending pathways between the cerebrum, cerebellum, and spinal cord.

First published on September 8, 2011

Last updated on September 20, 2025