The Paleocortex

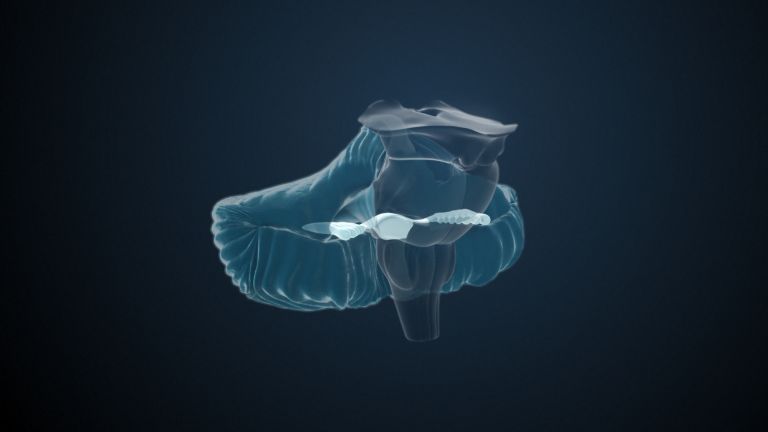

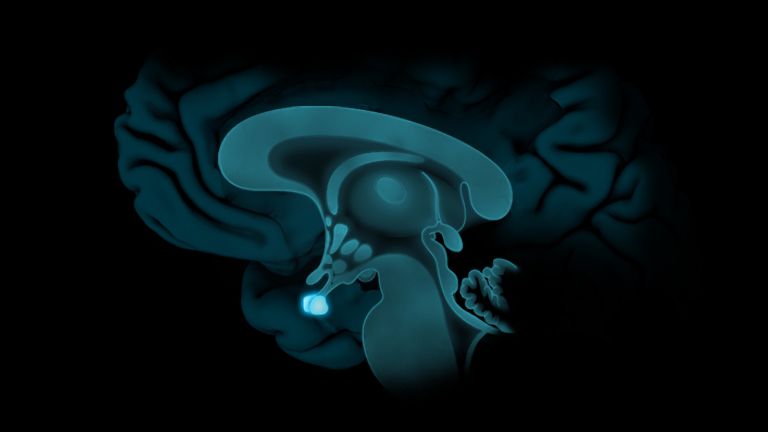

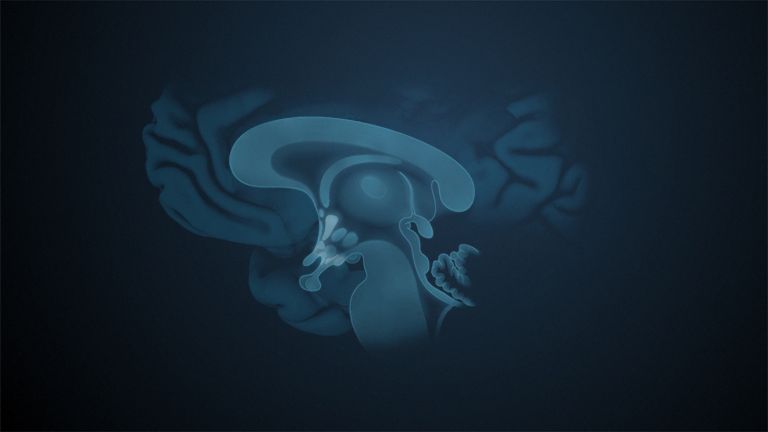

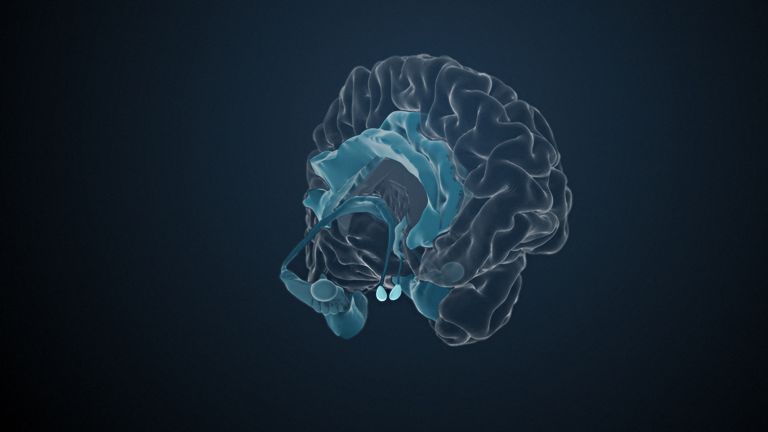

The oldest part of the cerebrum is responsible for smelling: the olfactory brain processes and discriminates between different smells. It includes the olfactory bulb, which resembles a butterfly's antennae. It also has a different structure to the rest of the cortex.

Scientific support: Dr. Björn Spittau

Published: 01.10.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

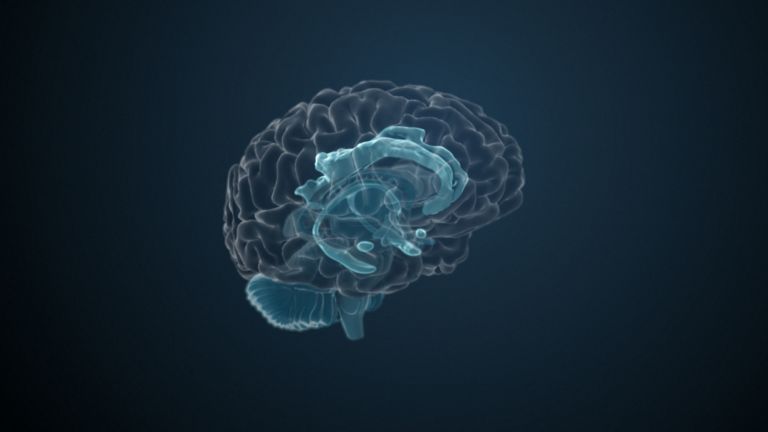

The paleocortex is the oldest part of the cerebrum and responsible for the sense of smell. Signals from the receptor cells in the nasal mucosa travel via the olfactory bulb to the primary olfactory cortex without first being switched in the thalamus. This distinguishes the sense of smell from all other sensory impressions.

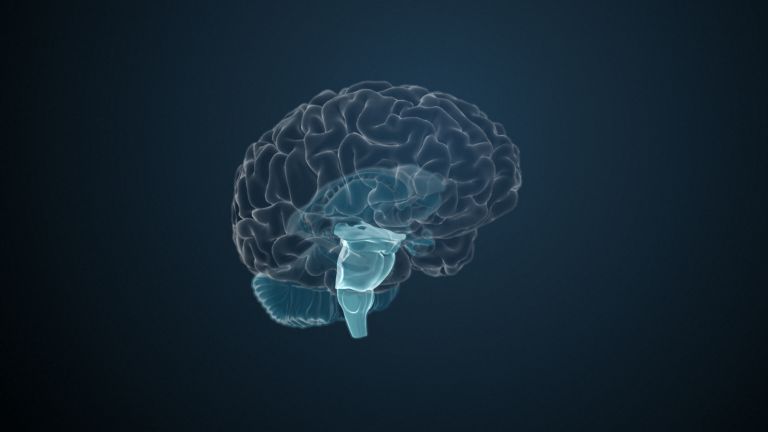

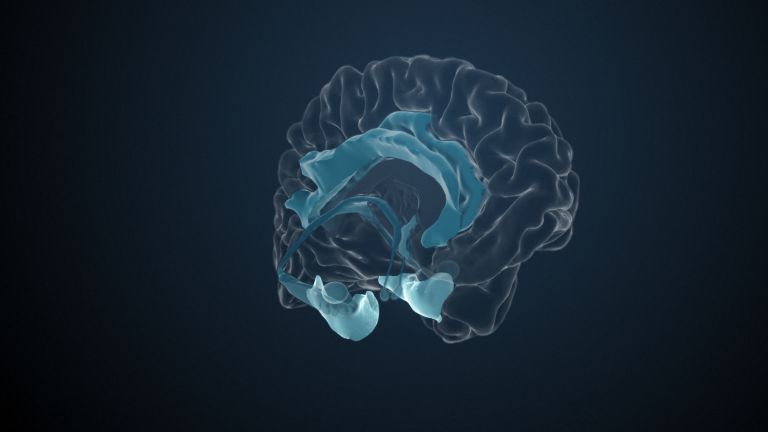

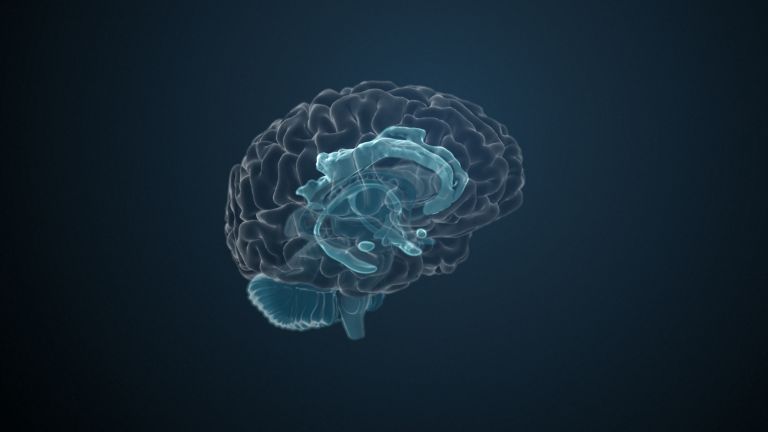

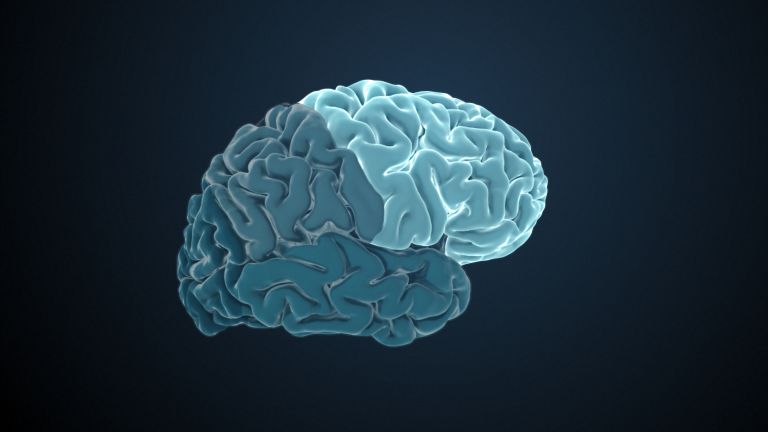

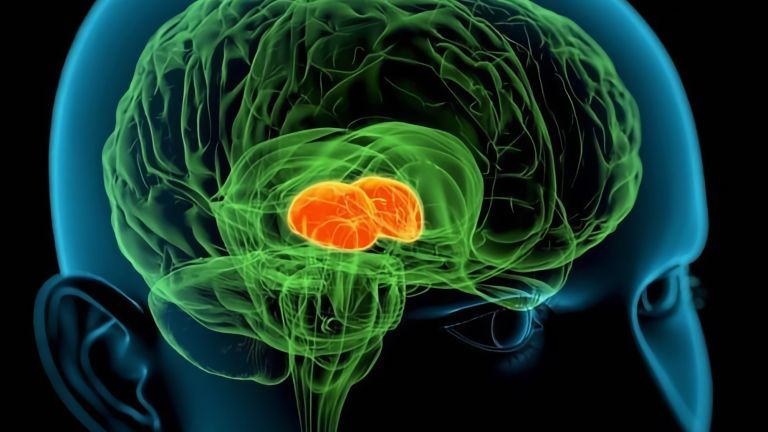

Paleocortex is the name given to the region of the brain responsible for the sense of smell. The developmental term paleo means primeval, emphasizing that it is the oldest part of the cerebral cortex. However, its age is not honored – over the course of evolution, the neocortex has displaced the paleocortex to the front lower surface of the two hemispheres.

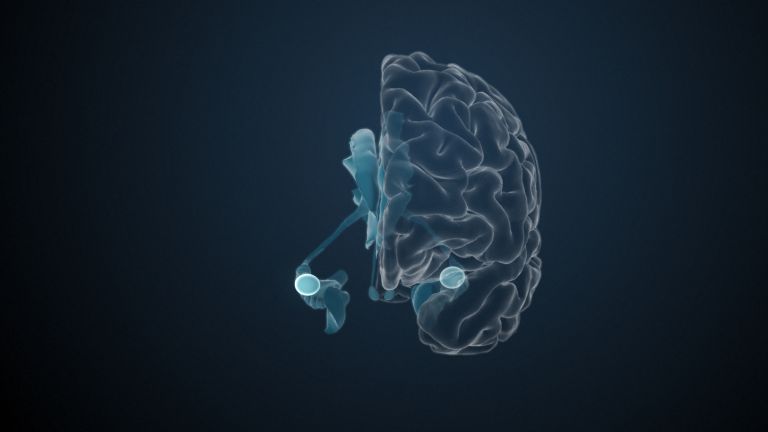

Nevertheless, from an evolutionary perspective, smell is a highly significant source of information. This is still evident today, because the sense of smell is something special. Unlike all other sensory impressions, odor information travels directly from the nose to the cerebral cortex without first being switched in the thalamus.

From the nose to the brain

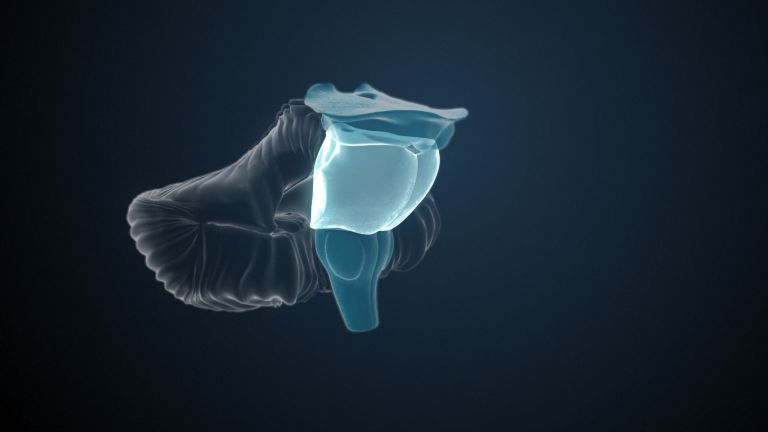

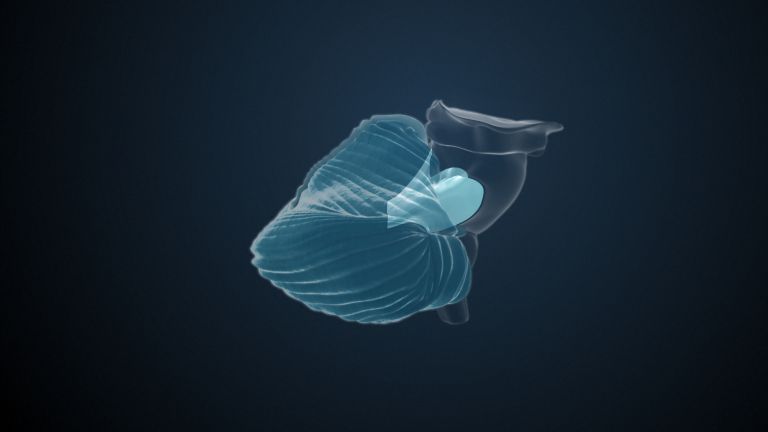

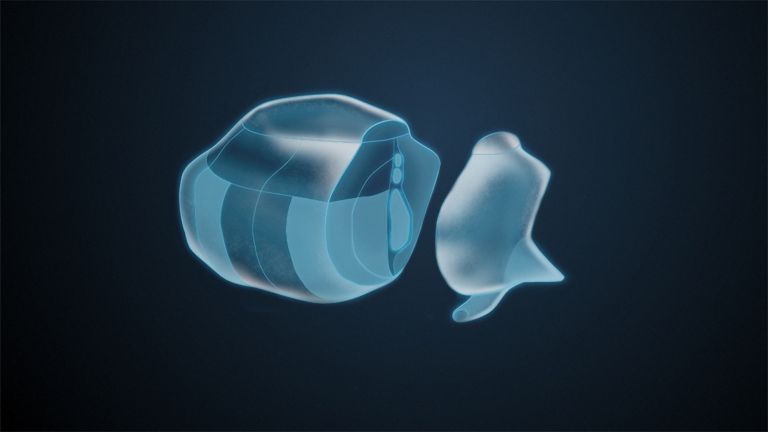

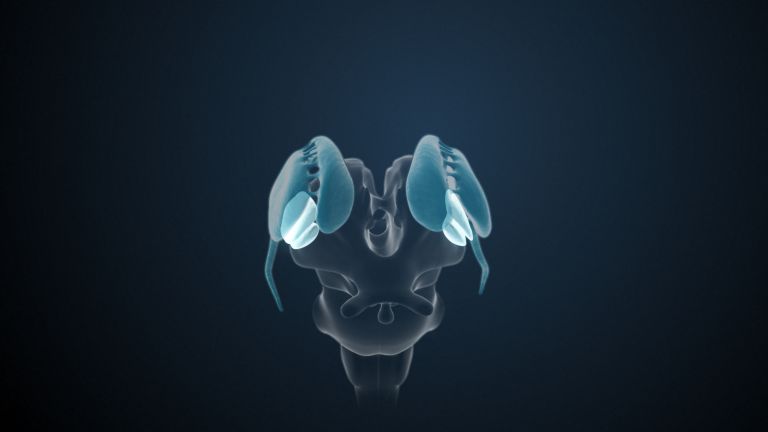

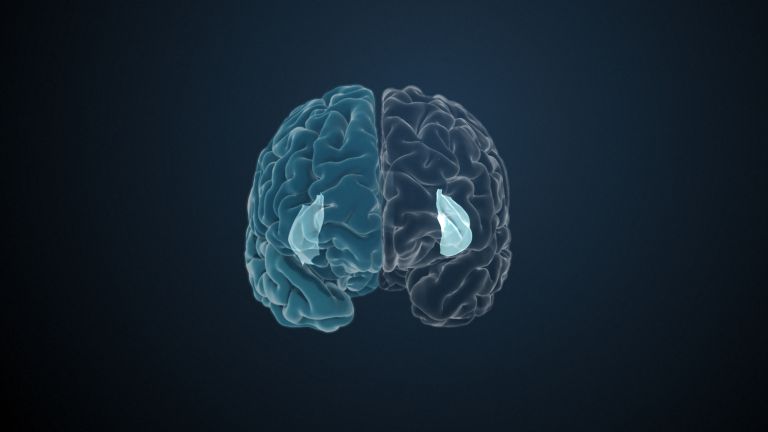

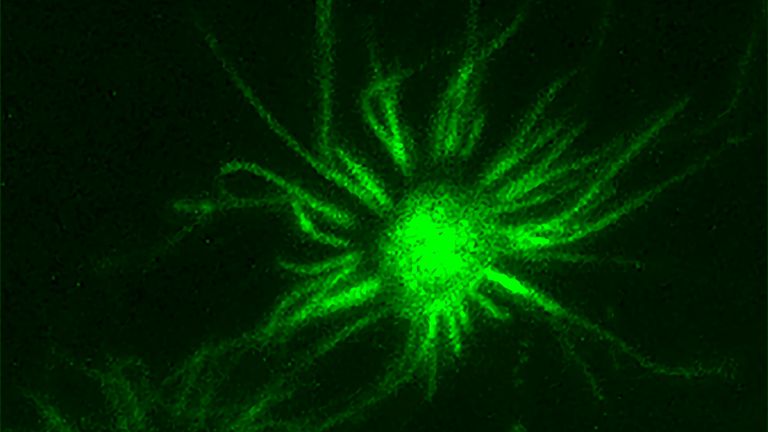

When a smell enters our nose, the olfactory receptor cells in the nasal mucosa register odor molecules. This is special in that the olfactory neurons are the only sensory neurons in mammals that are located directly on the body surface – even if this particular body surface is deep inside the nose. They transmit the information via their axons. And these axons – perhaps reflecting their evolutionary age – are not exactly the fastest. On the contrary: of all nerve fibers, the axons of the olfactory cells, the filae olfactoria, are the slowest. But slow or not, they form the actual olfactory nerve, the nervus olfactorius. This nerve extends to the olfactory bulb, the bulbus olfactorius – a protruding, flat, oval part of the cerebrum. Since this is the first switching station of the olfactory nerve, it can certainly be considered its cranial nerve nucleus.

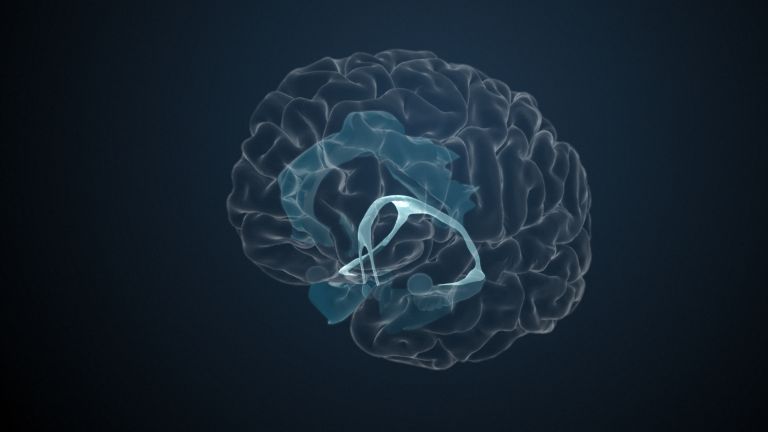

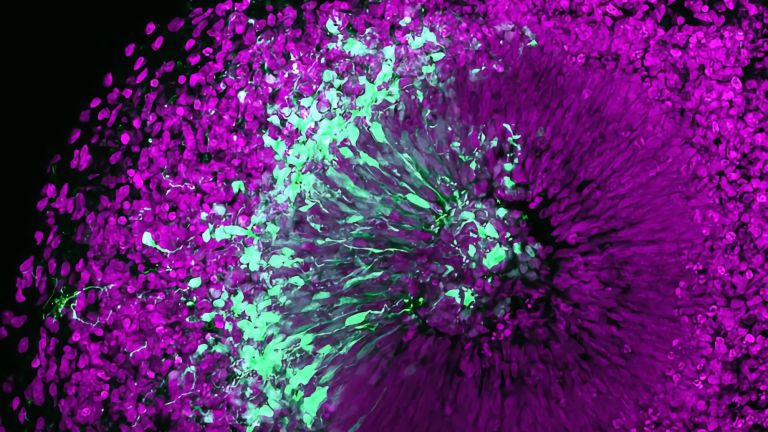

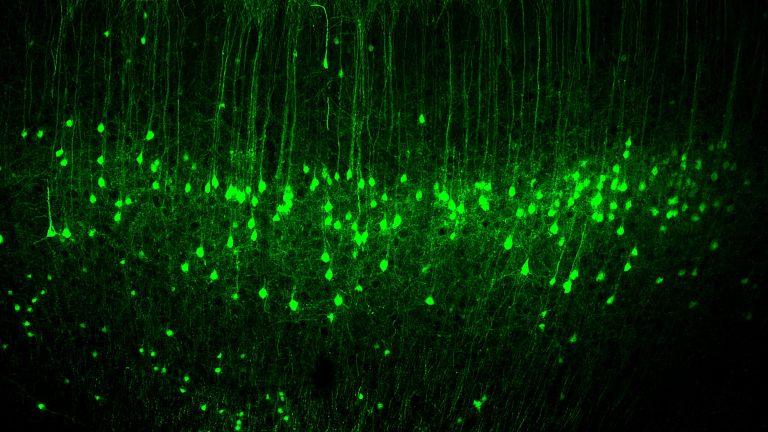

The olfactory bulb lies on the cribriform plate of the anterior cranial fossa, so that the filae olfactoria must first wind their way through the many small holes in this bony sieve. Only then can they unite to form the nervus olfactorius. In the olfactory bulb, it forms synapses with the dendrites of the mitral cells – so named because their nerve cell bodies look like little bishop's head covering. The place of encounter – and thus of switching – is the glomeruli. How well a living being can smell is decided here: In humans, the axons of many olfactory cells end at the dendrites of a mitral cell, meaning that the information converges. This makes us microsmatics, and our sense of smell is rather moderate. In dogs, which are macrosmatics, one sensory cell reaches several mitral cells; the odor signals are therefore distributed over a large area, and the olfactory “resolution” is higher.

Recommended articles

The path to the cortex

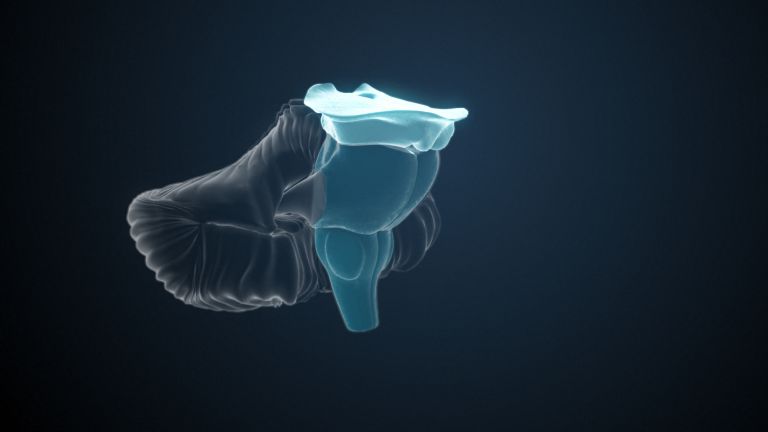

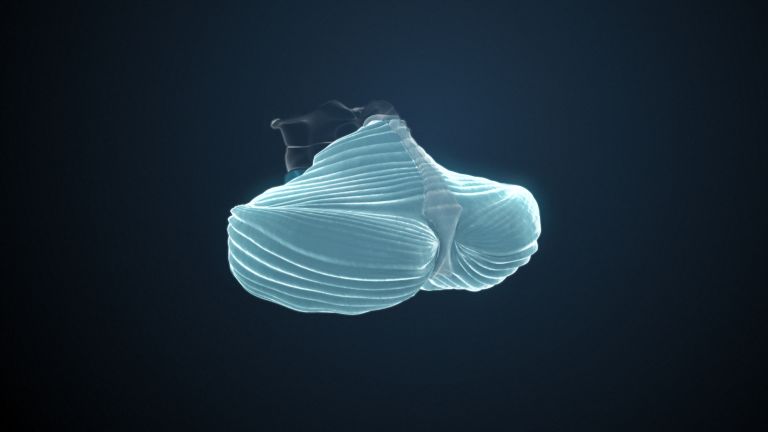

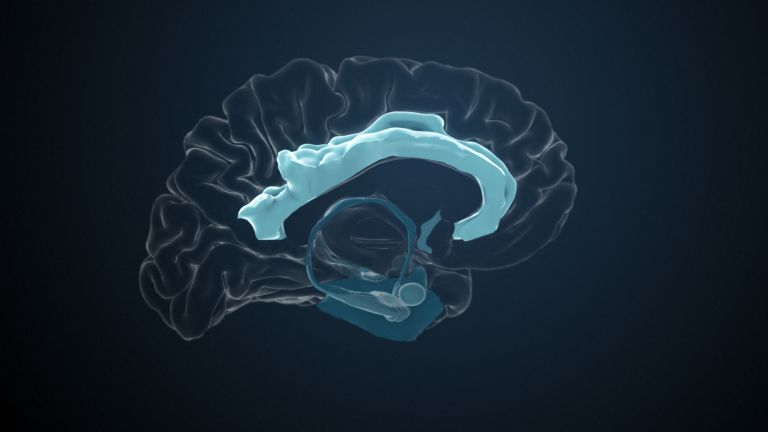

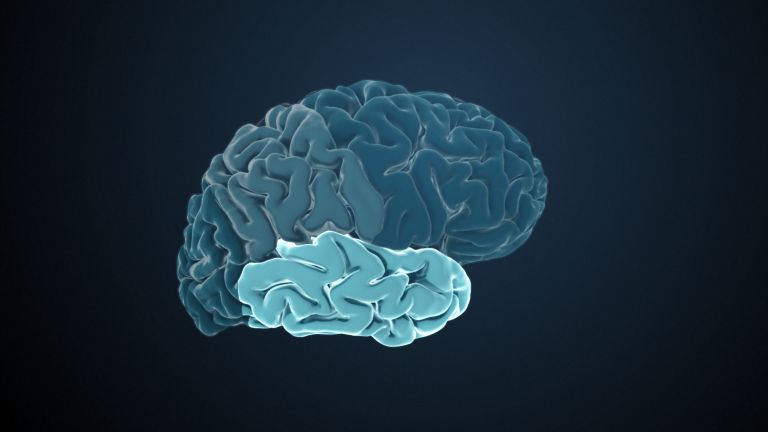

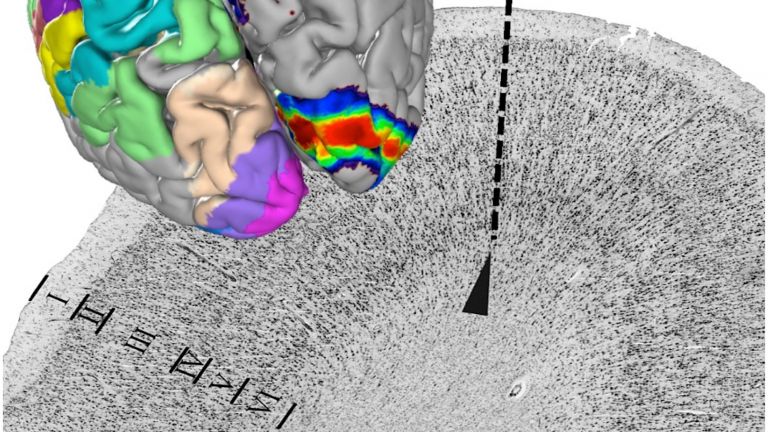

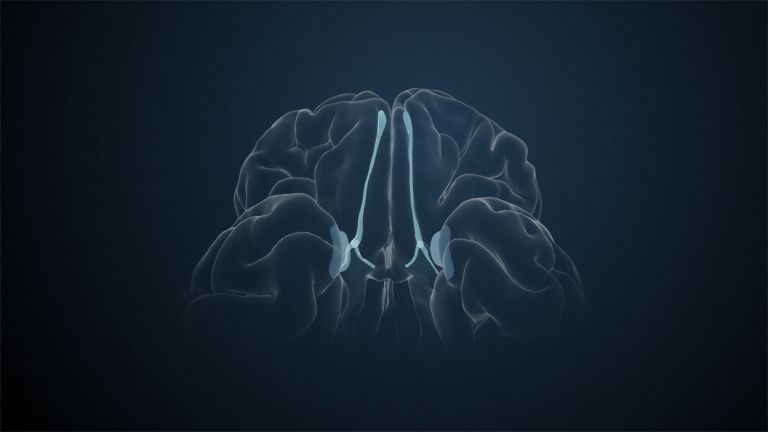

The axons of the mitral cells leave the olfactory bulb as the olfactory tract. Looking at the brain from below, these two tracts, together with the bulbs, are clearly visible: they are almost reminiscent of two butterfly antennae embedded in the frontal lobe from below.

After three to four centimeters, each of these antennae divides into the lateral and medial olfactory stria. At this fork, they form a triangle, the trigonum olfactorium, a thin layer of gray matter. This is where the anterior olfactory nucleus is located: it is a switching station for some axons of the olfactory tract – namely those that travel to the olfactory bulb of the other hemisphere. This means that both hemispheres constantly process the olfactory information from both nasal cavities, left and right.

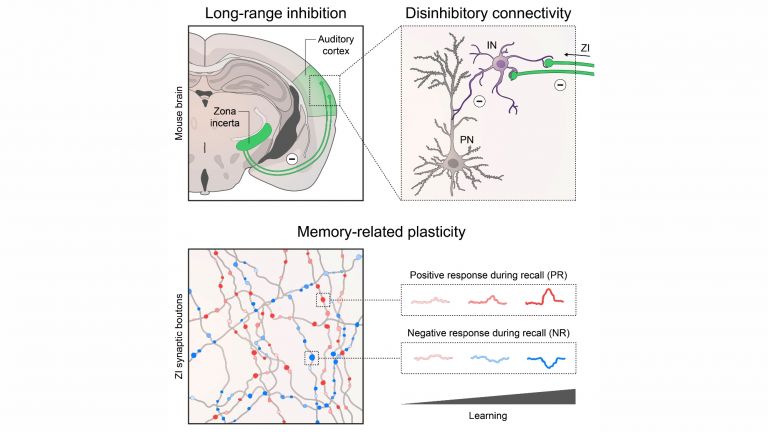

However, most mitral cell axons remain in the same hemisphere of the brain. The majority run as a lateral strand to the praepiriform area, which is considered the primary olfactory cortex. The cortex there is relatively thin and quite simple at the cellular level – we will come back to this later. Other fibers travel to the nuclei of the septum and via the olfactory tubercle to the thalamus and hypothalamus. Part of the amygdala is also considered part of the olfactory cortex, and olfactory signals reach the limbic system via this pathway. Last but not least, the olfactory cortex sends fibers directly to the hippocampus, which anchors smells in our memory.

With this network, it is no wonder that smells can trigger a variety of effects: disgusting smells make us feel nauseous, while the smell of tasty food makes our mouths water. We talk about not being able to “smell” another person, but when the chemistry is right, the smell of our partner arouses us sexually. And we never forget the smell of grandma’s apple pie.

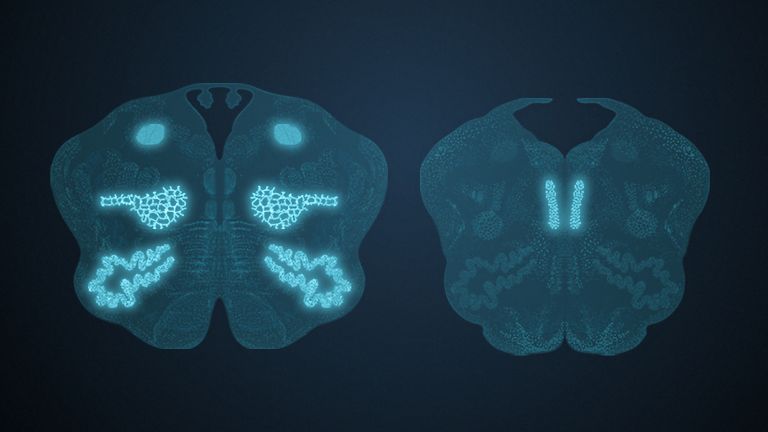

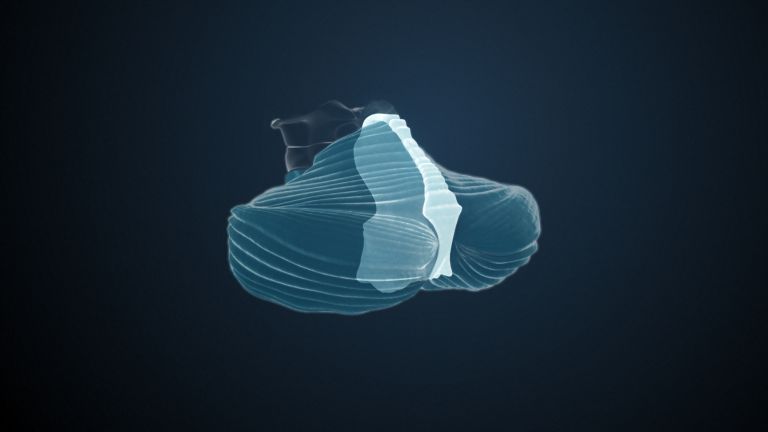

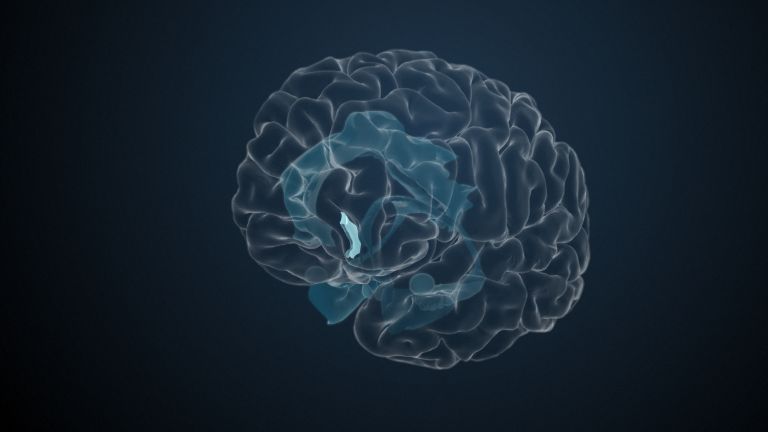

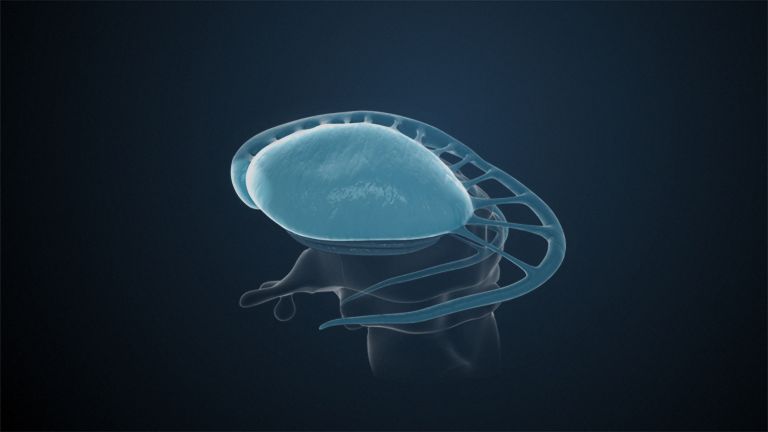

Cellular structure

“Allo” means “different” – the allocortex is therefore a cerebral cortex that is different. In contrast to the isocortex, which is made up of six layers throughout, the allocortex consists – presumably – of only three layers. The outermost layer is the molecular layer, the lamina molecularis: this is where the dendrites of the pyramidal cells from the middle layer, the pyramidal cell layer (lamina pyramidalis), branch out. Their axons pass through the underlying lamina multiformis, which contains nerve cells of various shapes, into the cerebrum. Between the lamina molecularis and the lamina multiformis, there is therefore only a single layer of nerve cells – in the isocortex, there are four: two layers of granule cells and two layers of pyramidal cells alternating with each other.

However, the number of layers in the allocortex can vary greatly. Even textbooks disagree on how many there normally are. Some say three to five, others say a maximum of four, and still others limit themselves to “usually three”. In humans, there are only two at the olfactory tubercle, where the outer molecular layer is partially missing.

First published on August 31, 2011

Last updated on October 1, 2025