The Basal Ganglia

They are called caudate nucleus and putamen, are “torn” by fiber tracts, and lie deep within the brain. Every movement we perform deliberately is the result of their extensive networking, their mutual inhibition, and excitation.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Horst-Werner Korf

Published: 23.08.2011

Difficulty: intermediate

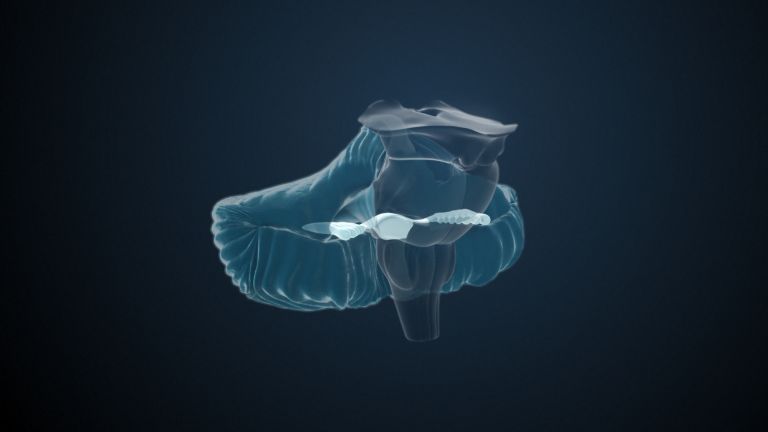

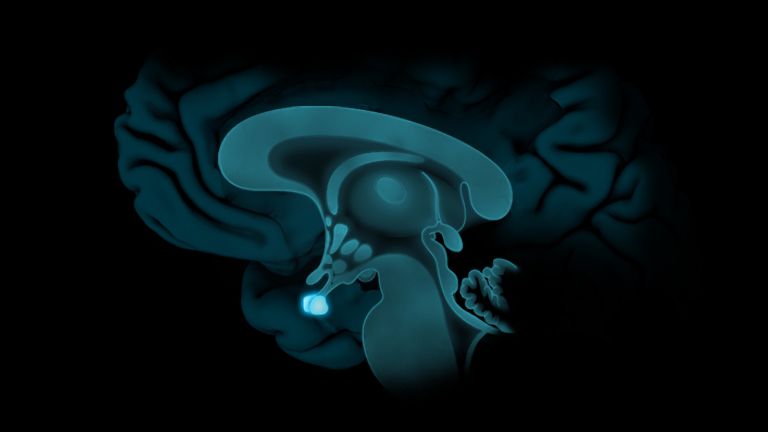

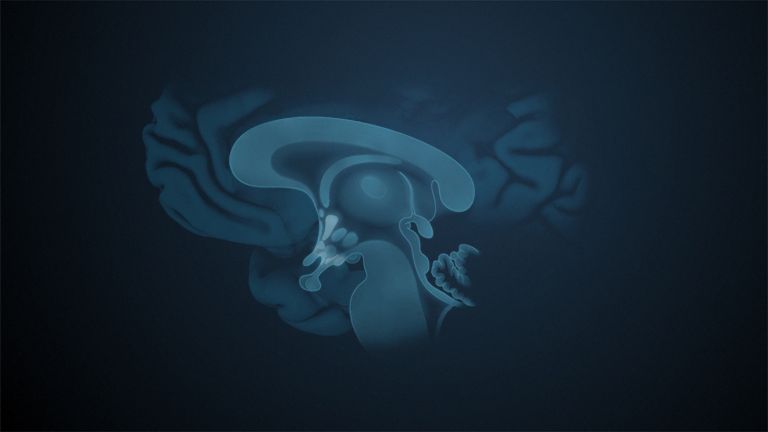

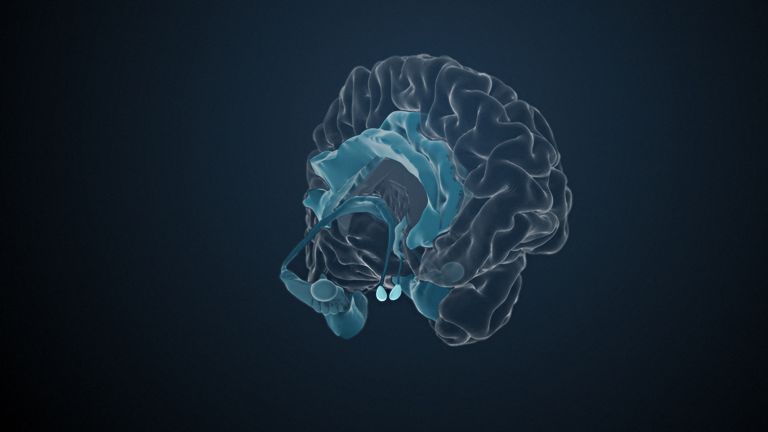

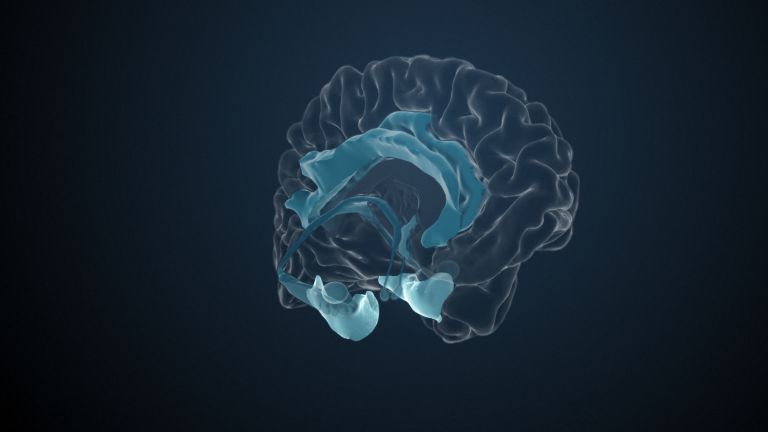

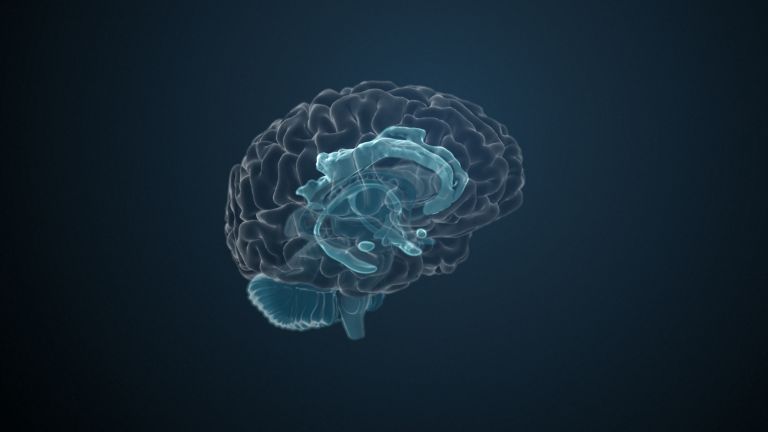

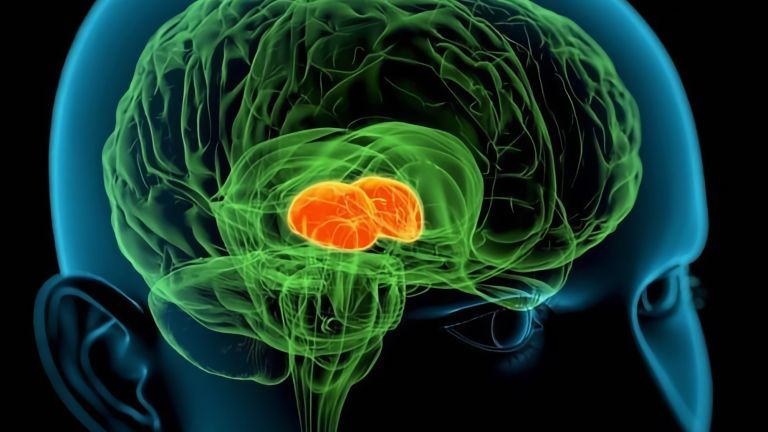

The basal ganglia are non-cortical gray matter of the cerebrum whose main function is the global regulation of voluntary motor activity. As a student of anatomy, you should know: caudate + putamen = striatum, putamen + pallidum = lentiform nucleus.

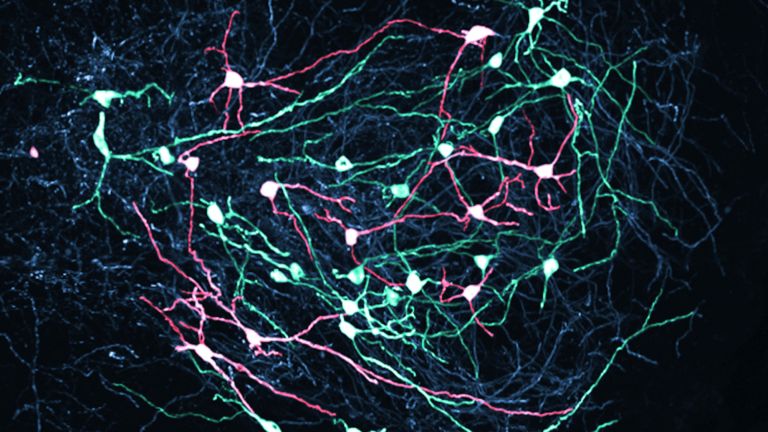

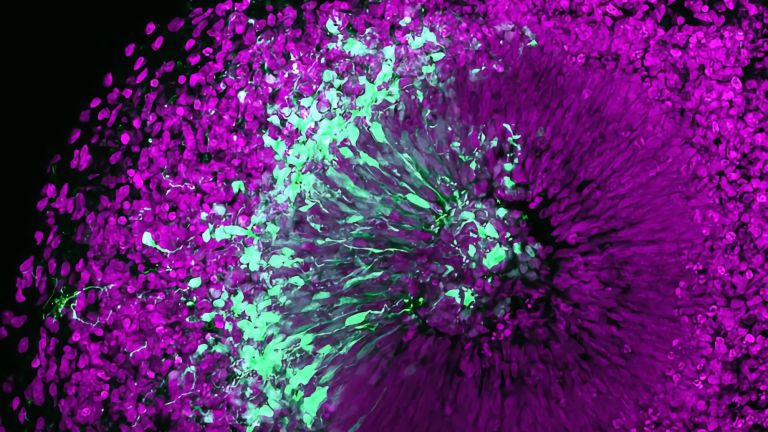

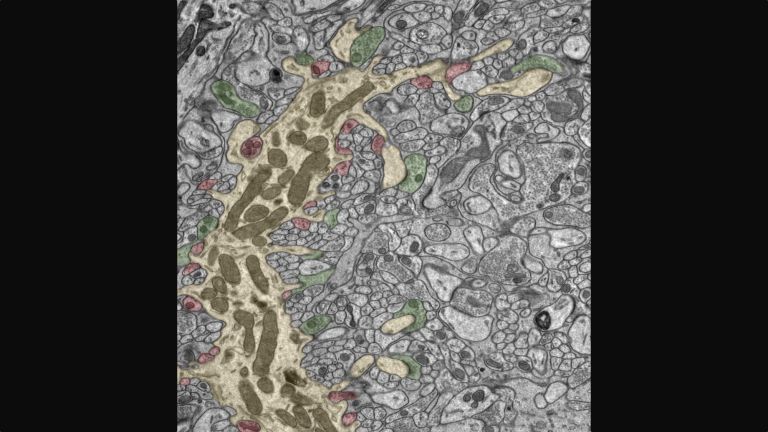

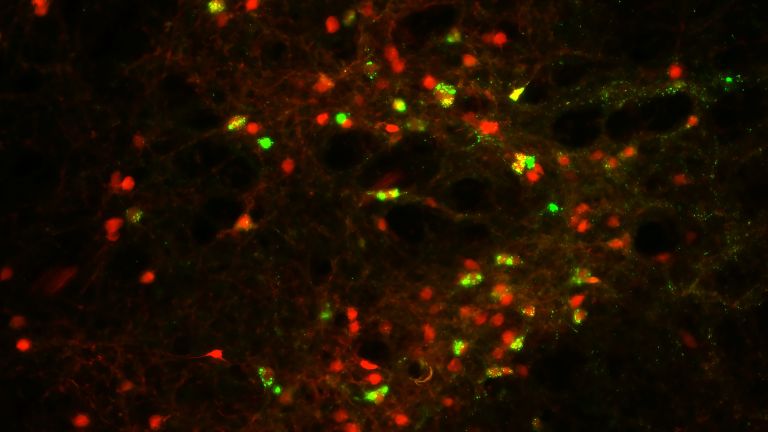

The brain has gray matter and white matter. The white matter consists mainly of nerve fibers. Such a nerve fiber typically consists of the axon of the nerve cell, which is surrounded by special glial cells called oligodendrocytes. The largest fiber connection in the brain is the corpus callosum between the two hemispheres. The gray matter consists of the cell bodies of the nerve cells, the well-known little gray cells – which, however, are by no means gray in the living brain, but rather pink. In addition, many special glial cells (mainly astrocytes) are also found in the gray matter. The gray matter occurs in the brain in layers, cortical, or in clusters as nuclei.

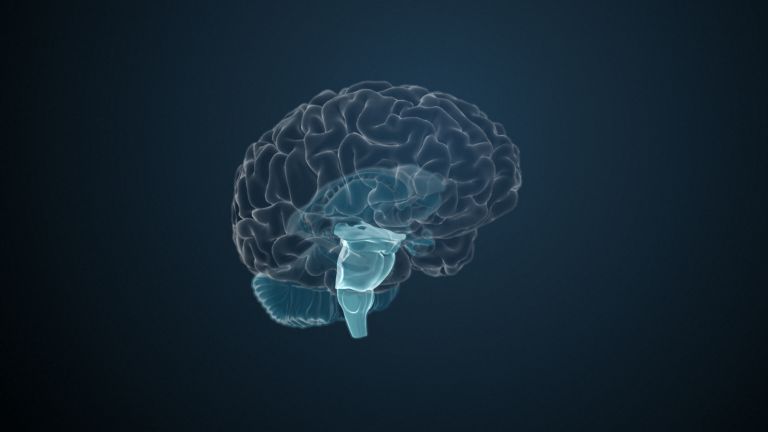

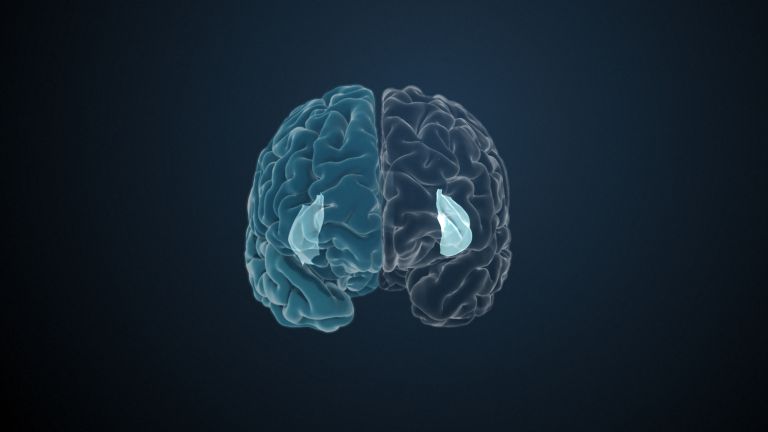

The gray matter of the telencephalon can be roughly divided as follows: On the one hand, there is the cortex (literally: the “bark”), which lies just below the convoluted and folded surface of the telencephalon. And on the other hand, there are large, lumpy aggregates located in the center, at the base of the telencephalon, very close to the lateral ventricles. The basal ganglia belong to these “non-cortical” gray masses.

What are they – and what are they not?

The collective term “basal ganglia” is not clearly defined and has changed over time. Some regions that were previously included under this term have now been excluded for functional reasons, as they are not directly part of the motor system. This is because the regulation of voluntary motor function and motor memory are the core tasks of the basal ganglia.

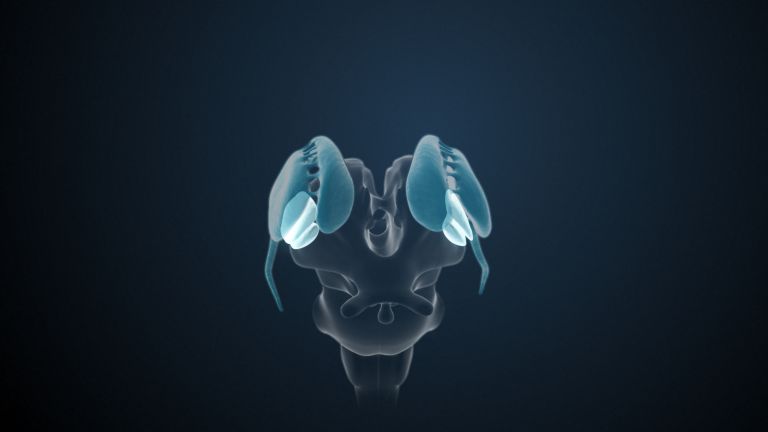

It has proven useful to approach the basal ganglia using a kind of “historical exclusion process.” For a long time, the gray masses flanking the third ventricle of the diencephalon on the right and left sides are not considered being part of the basal ganglia: These are the two thalami. The amygdalae, the almond-shaped nuclei located on both sides inside and above the temporal lobe and in front of the pes hippocampi (like a soccer ball in front of a soccer shoe, i.e., the pes hippocampi), are also no longer considered part of the basal ganglia. Most experts now assign them to the limbic system because they serve the affective rather than the motor system.

In addition, the claustrum is no longer considered part of the basal ganglia. This is the layer of gray matter located just below the cortex of the insula (where Nobel Prize winner Francis Crick believed consciousness to be located). Current research suggests that the claustrum is a piece of “scattered cortex” that may be involved in cognitive functions, desires, and addictions.

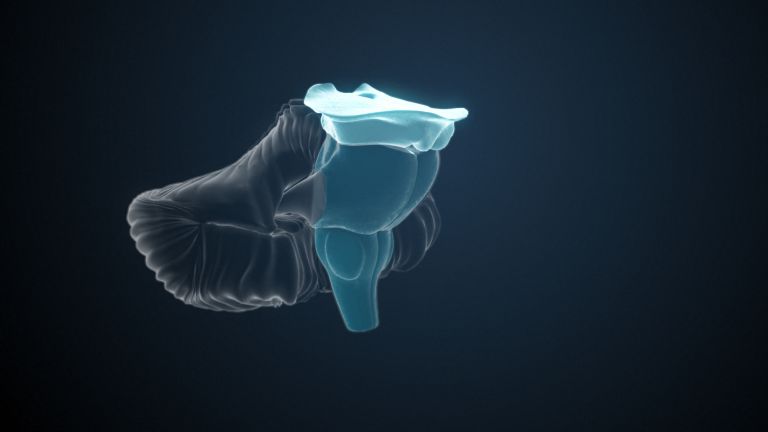

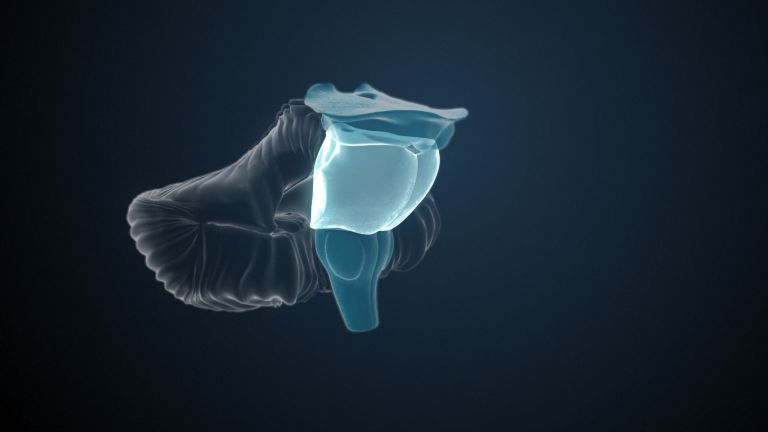

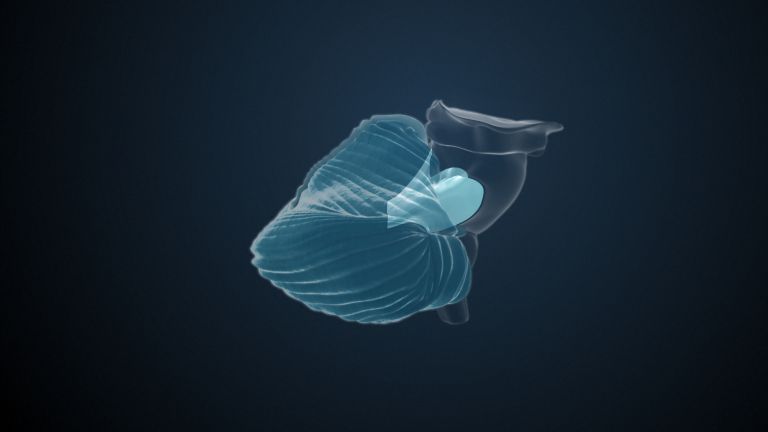

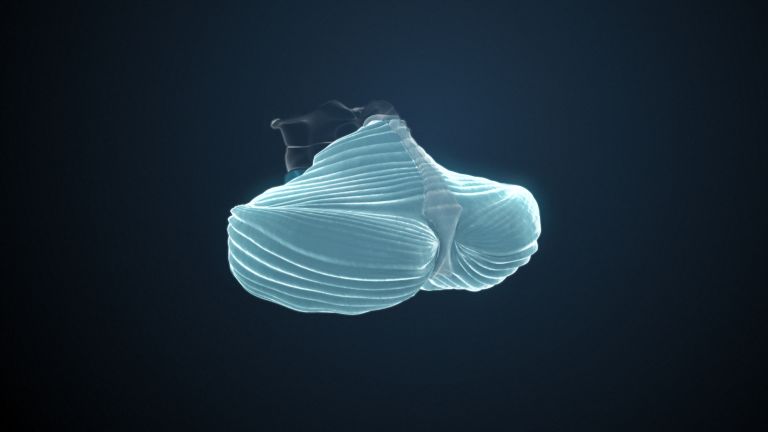

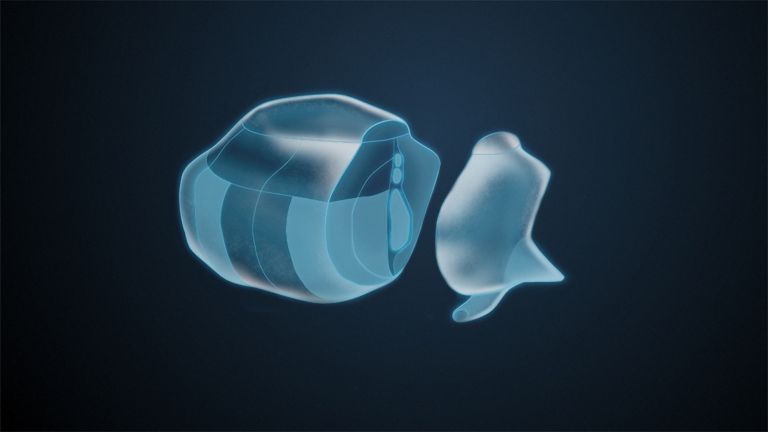

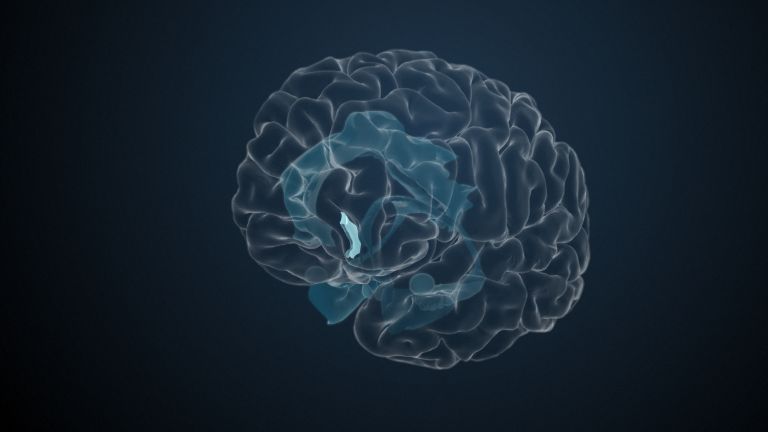

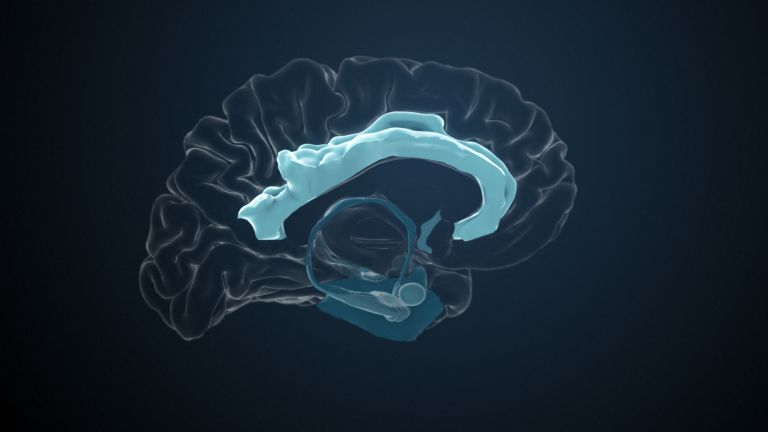

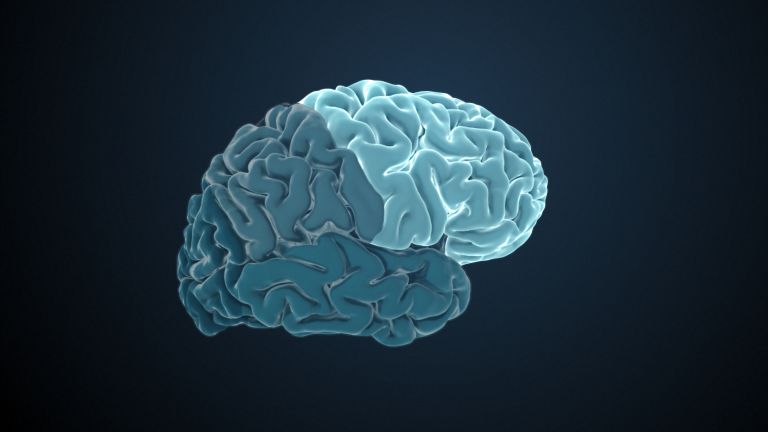

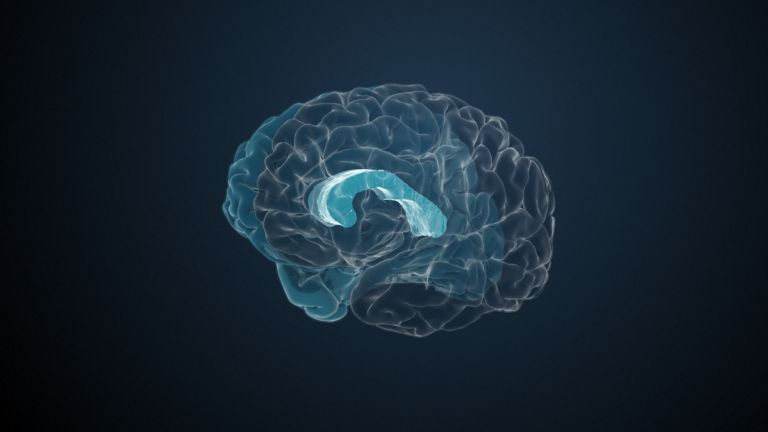

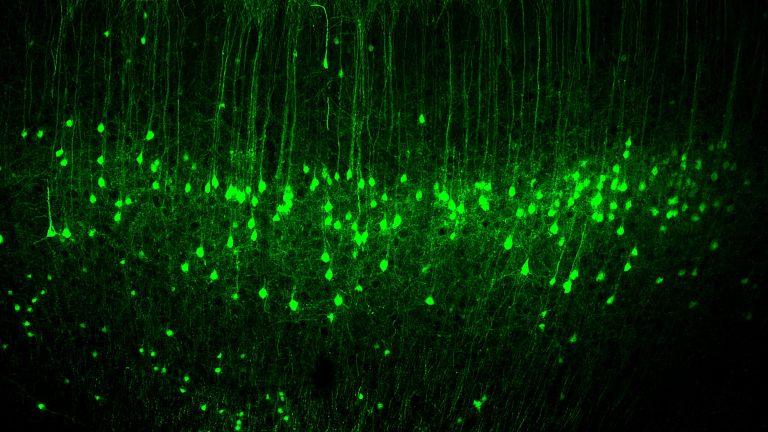

This leaves the motor basal ganglia in the narrower, modern sense, namely the caudate nucleus (the “tail core”) and the putamen (the “shell core”). The caudate nucleus, the “tailed nucleus,” has a very peculiar, curved shape. It follows the curved contour of the lateral ventricle, to which the caudate nucleus is directly adjacent. Particularly in its thick front section, known as the head or caput nuclei caudati, the caudate nucleus is connected to the putamen by many bridges of gray matter.

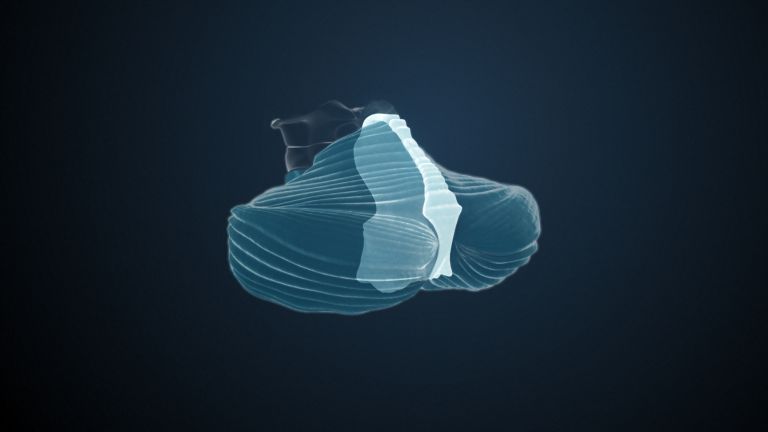

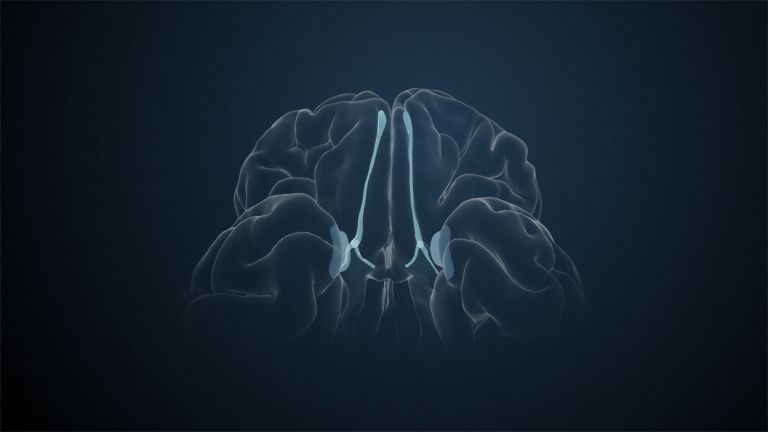

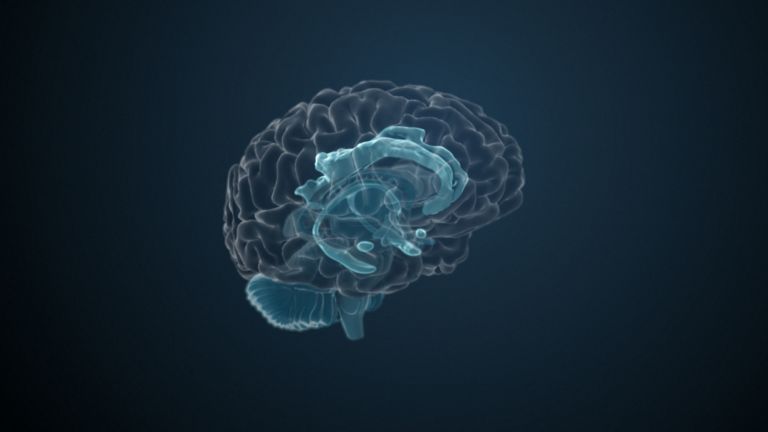

In fact, both were originally – both in terms of phylogenetic development and embryonic development – a single core area. It was only “torn apart” by a massive bundle of white matter that pushed between them. This bundle of fibers is the internal capsule, in which the cortical efferents descending to other regions, but also the reciprocal thalamocortical fiber connections, are bundled. When viewed together, the gray bridges mentioned above and the white fiber bundles of the internal capsule that squeeze in between them actually form a gray-white striped pattern in the sectional view – especially in the anterior part of the basal ganglia, which lies between the putamen and the head of the caudate nucleus. This has earned them the name “striatum.”

At the very front and very bottom, the head of the caudate nucleus and the base of the putamen are actually still completely undivided and connected by a broad bridge of gray substance. This is the nucleus accumbens septi, also known as the ventral striatum or fundus striati.

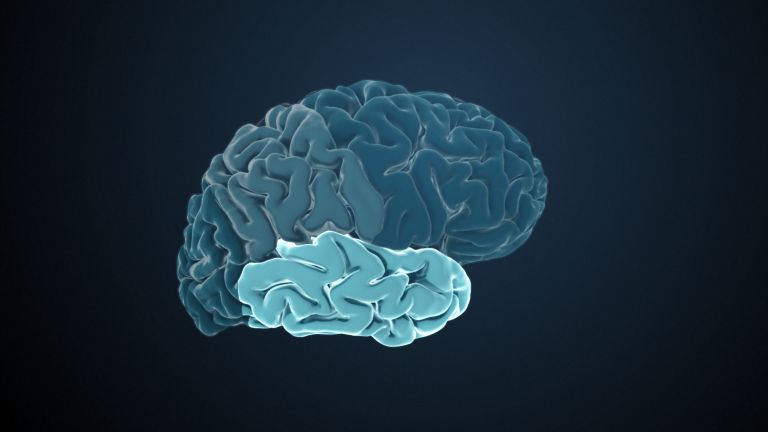

Finally, there is the globus pallidus, which literally means “pale sphere.” It is often simply referred to as the pallidum. The pallidum is pale because its nerve cells – unlike those of the other basal ganglia – contain very little pigment (neuromelanin and lipofuscin). The pallidum is located close to the putamen, toward the center, toward the diencephalon. Together, the putamen and pallidum are also referred to as the “lentiform nucleus.” This term, which is based on their purely macroscopic appearance, should no longer be used today, as it combines sections that are completely different in terms of their developmental history and function. Here, too, the internal capsule has done its disruptive work: the pallidum originally belonged to the diencephalon, in the ventral thalamus, through which the internal capsule also grew. It thus pushed the pallidum to the side, toward the putamen. What remained of the ventral thalamus in its original location is now called the subthalamic nucleus.

Recommended articles

Function

The ventral striatum is part of our “reward system.” The nerve cells there are primarily activated when we expect or receive a reward or satisfaction. The ventral striatum therefore also plays an important role in all kinds of addictions and in both good and bad habits.

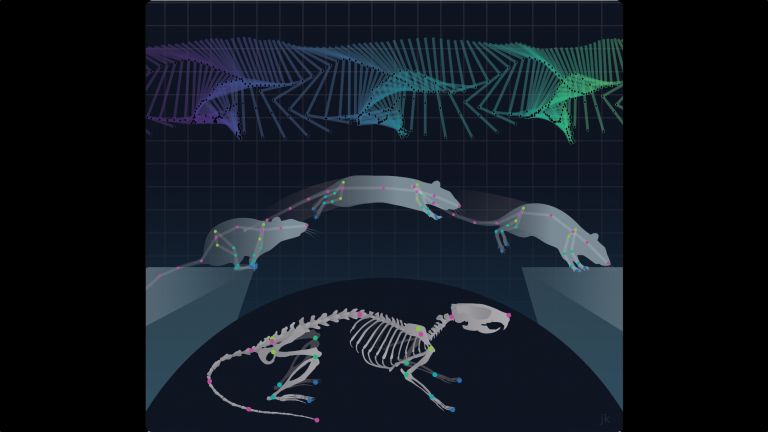

The remaining, much larger areas of the basal ganglia, i.e., the caudate, putamen, and pallidum, are responsible for motor function, or more precisely, its regulation. In particular, they serve to initiate, i.e., actually start, and terminate voluntary motor acts. They also contain part of our motor memory. These are motor skills such as running, riding a bike, or playing the piano, which we acquire over the course of our lives.

In simple terms, it can be said that disturbances in the function of the basal ganglia are associated with global motor deficits. It is not individual muscle groups or extremities that are affected. Rather, all muscles suffer from similar coordination problems. The “paradigmatic” basal ganglia disorder is Parkinson's disease, which is characterized by increased muscle tone, i.e., rigidity, lack of movement, slow and limited movements, and the well-known tremor (shaking).

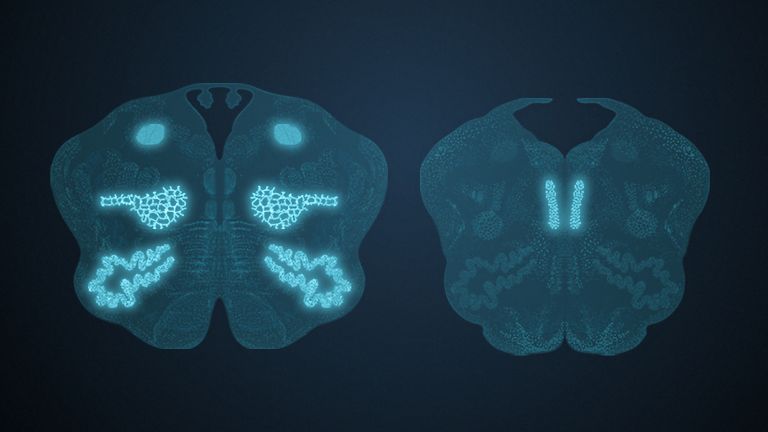

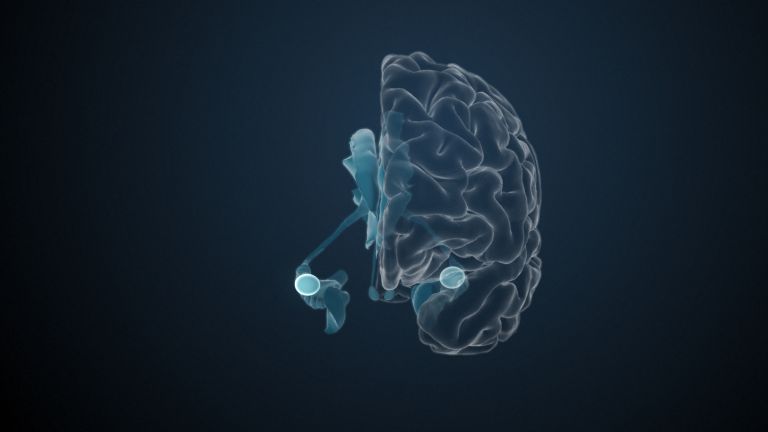

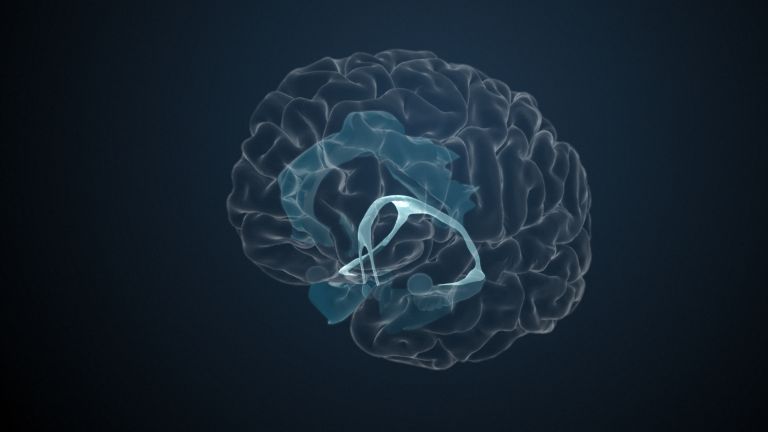

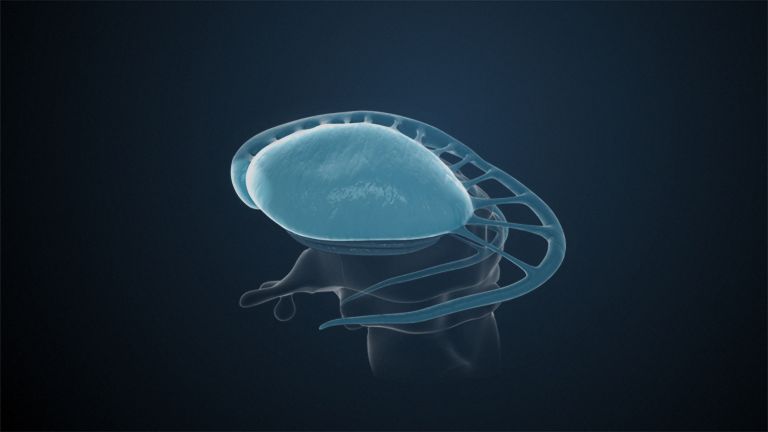

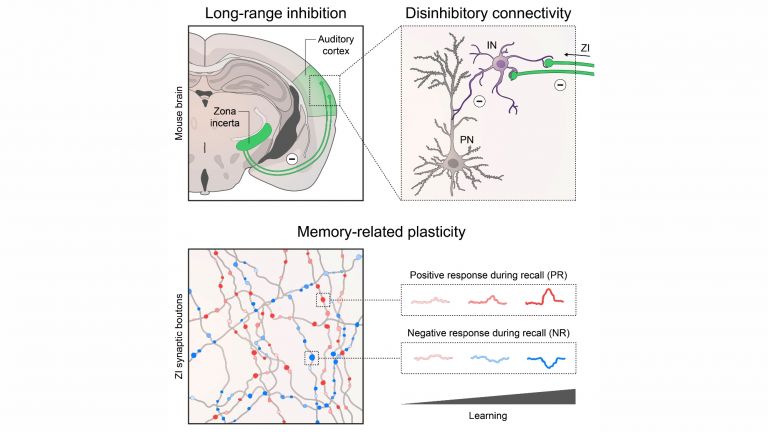

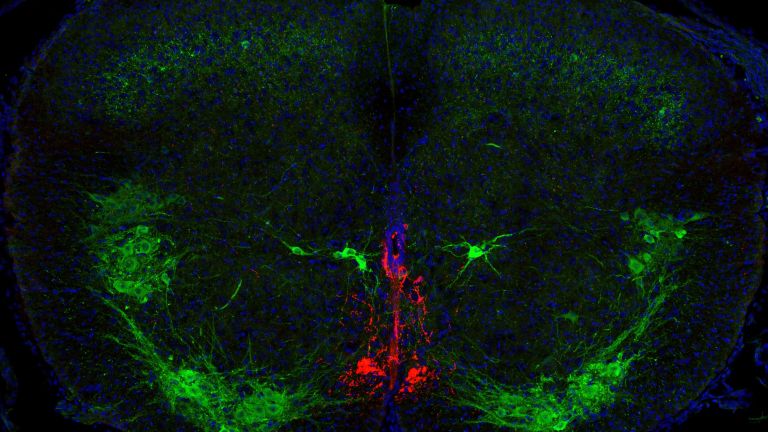

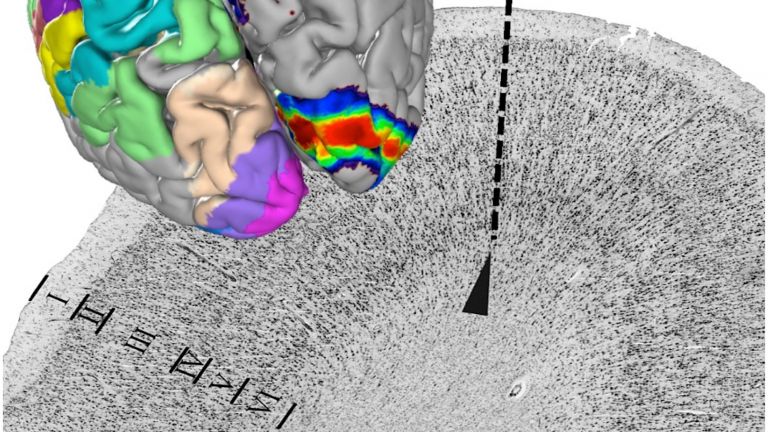

It should be noted that the basal ganglia do not exert their regulatory influence on the motor system directly, but via a neural loop that connects them to the thalamus and the (motor) cortex. When a movement is to be initiated, the cortex sends excitatory impulses via glutamatergic fibers down to the basal ganglia and into the putamen and the caudate nucleus, which represent, so to speak, the “input” side of the basal ganglia. The shell and caudate nuclei in turn send inhibitory impulses to the pallidum. Its fibers, which also use the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA, act as the “output” of the basal ganglia to a nucleus in the dorsal thalamus. However, the inhibition of an inhibition (disinhibition) is equivalent to excitation. Therefore, this thalamic nucleus becomes active when the cortex is active, as well. The thalamic nucleus (called the ventrolateral anterior nucleus) sends its fibers to those areas of the cortex whose nerve cells then send the actual motor pathways that descend to the motor neurons in the brain and spinal cord.

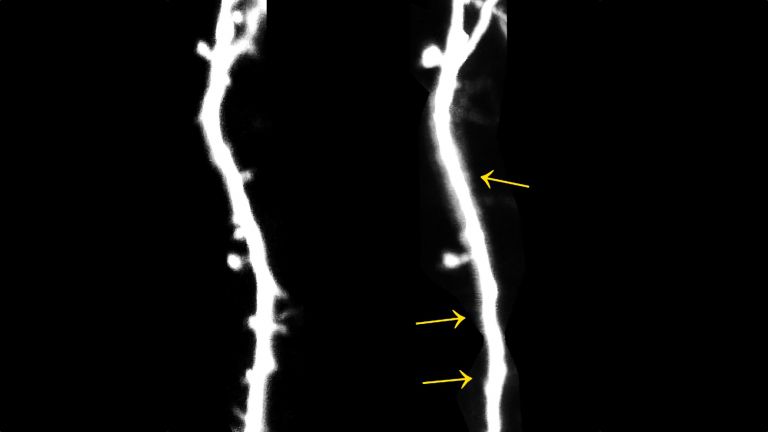

The well-known substantia nigra, the “black nucleus” of the midbrain, is also involved in the regulation of this “cortico-basal ganglionic-thalamo-cortical” loop. The basal ganglia send efferents there, partly directly and partly via the subthalamic nucleus of the diencephalon. The substantia nigra, in turn, sends dopaminergic axons, the nigrostriatal tract, to the striatum, whose neurons receive the dopamine signals via presynaptic dopamine transporters (DaT) and postsynaptically located D2 receptors. When there is a dopamine deficiency, the expression of DaT is downregulated. If there is a lack of dopamine in the striatum – for example, in Parkinson's disease, because the nerve cells in the substantia nigra have died – this results in the notorious rigidity and lack of movement. Conversely, for example in the case of damage to the subthalamic nucleus or the pallidum, uncontrolled and completely involuntary “movement outbreaks” of individual extremities or even the entire body can occur, which cannot be stopped at will.

Then there is Huntington's disease, a hereditary disorder of the central nervous system which, like Parkinson's disease, is a multisystem disorder of the central nervous system with “movement outbreaks.” It leads to the loss of neurons in the striatum and manifests macroscopically as a flattening of the caudate nucleus with corresponding enlargement of the lateral ventricles. The cause is a mutation in the huntingtin gene, which leads to an increase in the base triplets CAG (cytosine, adenine, guanine) and is therefore referred to as a trinucleotide disorder.