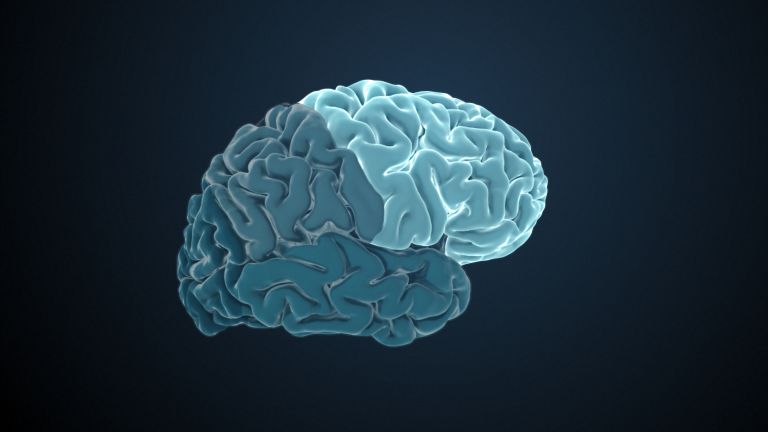

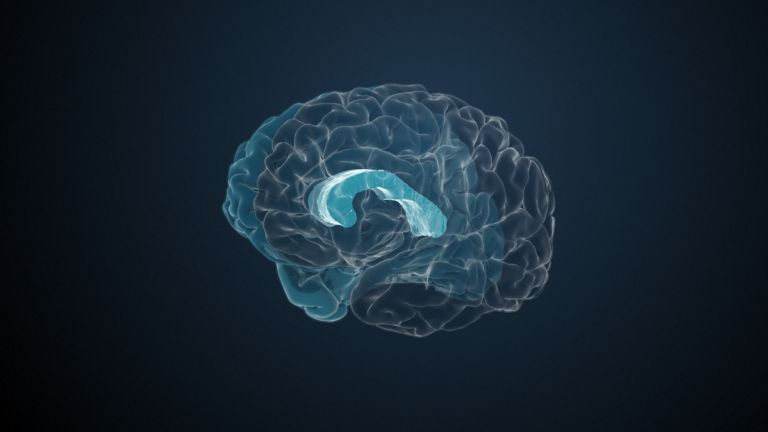

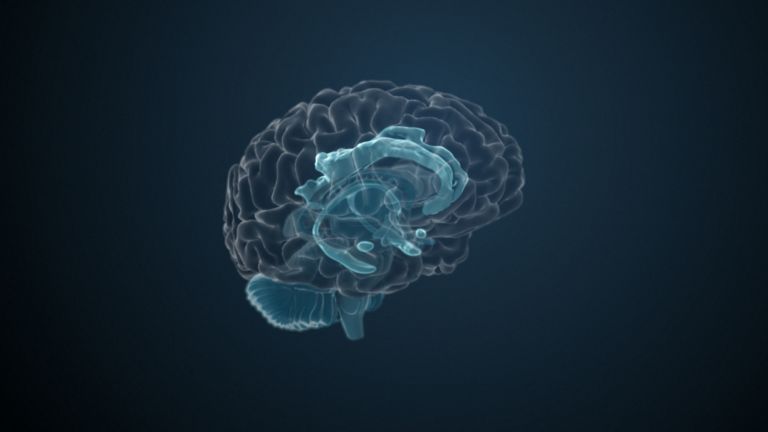

The Temporal Lobe

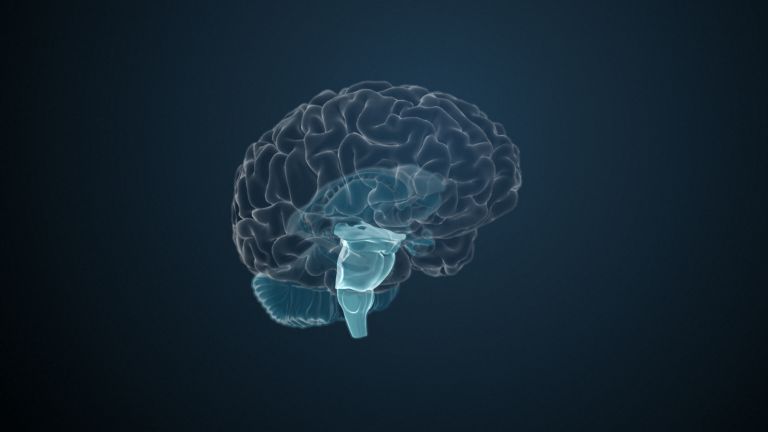

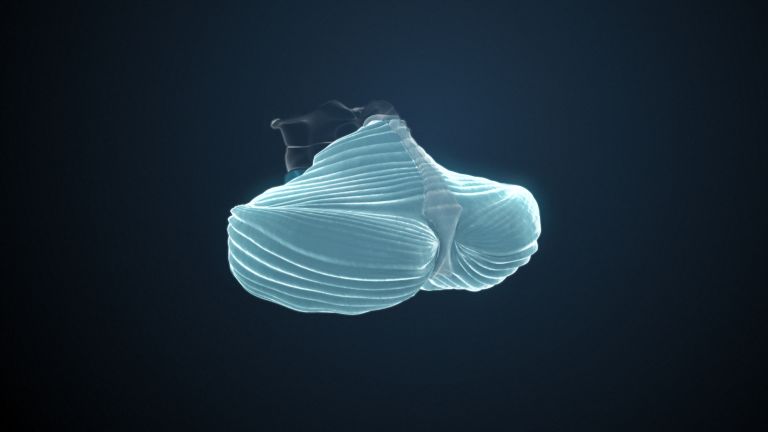

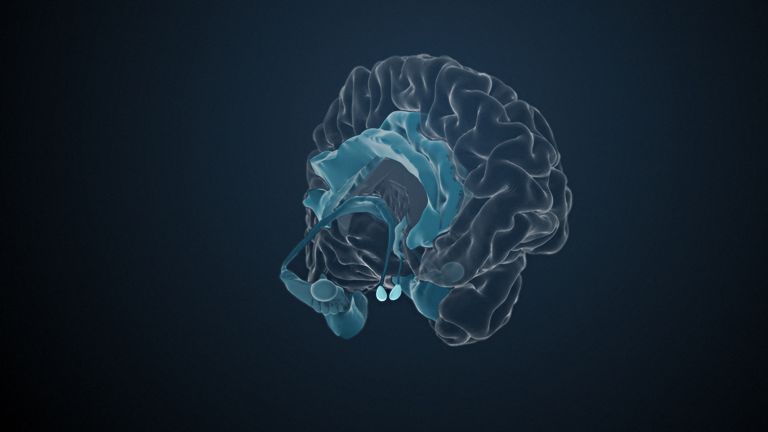

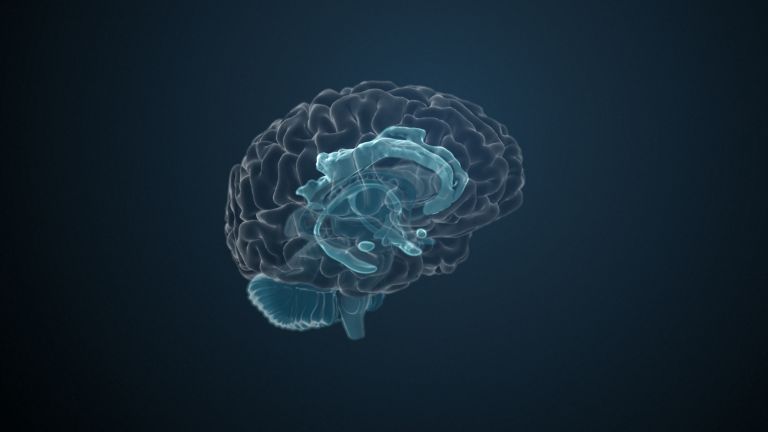

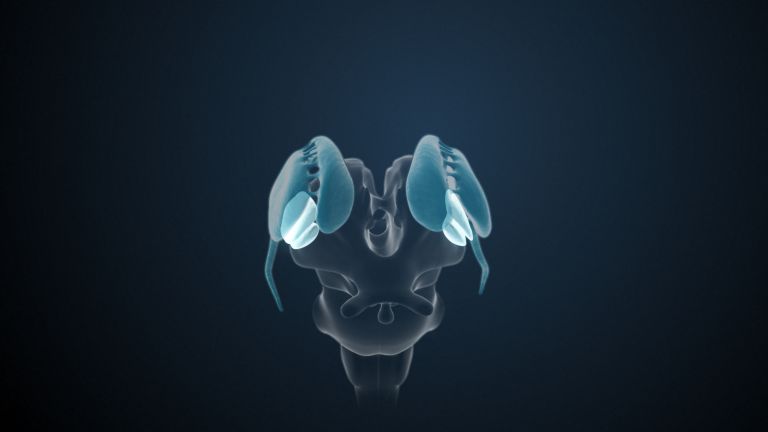

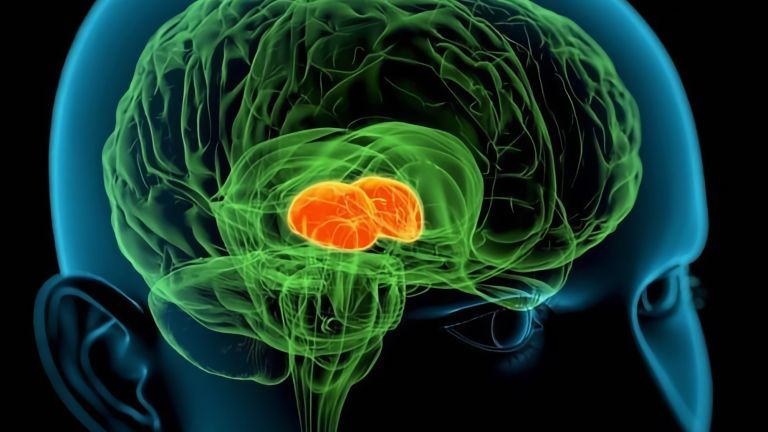

The two temporal lobes frame the brain stem. They consist of iso- and allocortical regions and also contain the non-cortical core areas of the amygdala. The temporal lobe is truly “multimodal,” serving numerous functions with many different centers: smelling, hearing, speaking, understanding, visual recognition, and memory formation.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Horst-Werner Korf

Published: 28.11.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

The two temporal lobes frame the brain stem. They consist of iso- and allocortical regions and also contain the non-cortical core areas of the amygdala. The temporal lobe is truly “multimodal,” serving numerous functions with many different centers: smelling, hearing, speaking, understanding, visual recognition, and memory formation.

Before any misunderstandings arise, we should clarify one thing: in anatomy, the term “temple” refers to the region just in front of and directly above the ears. The largest part of the temporal lobe lies beneath this area. The temple in colloquial language, on the other hand, is further forward. And beneath it lies the frontal lobe.

Regions and structure

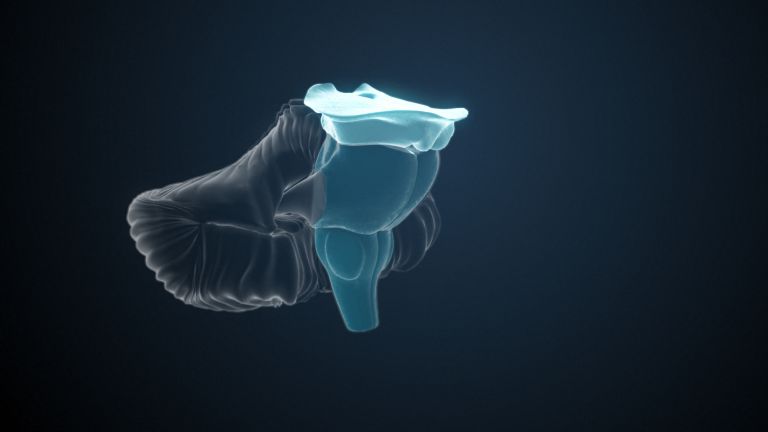

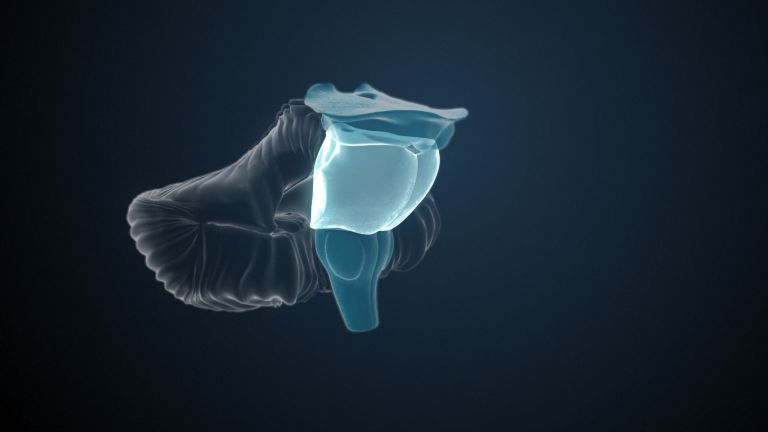

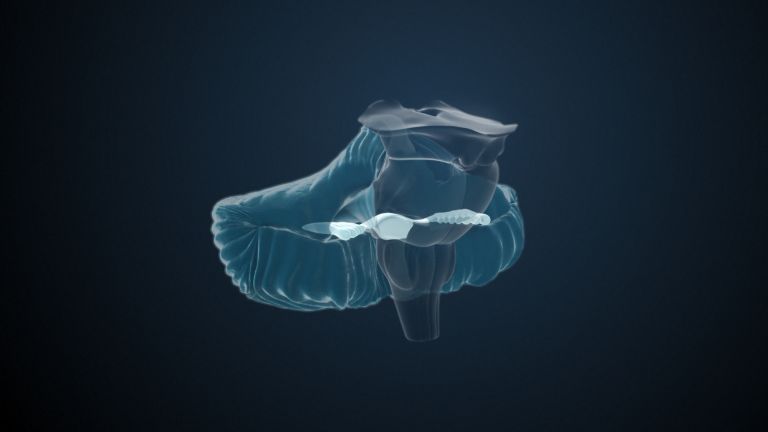

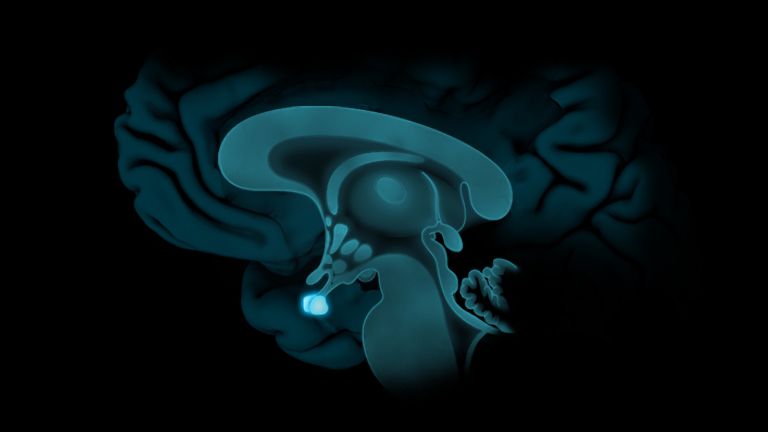

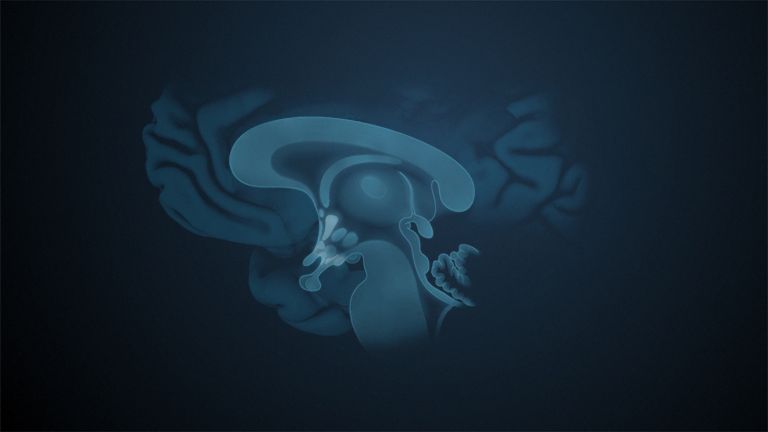

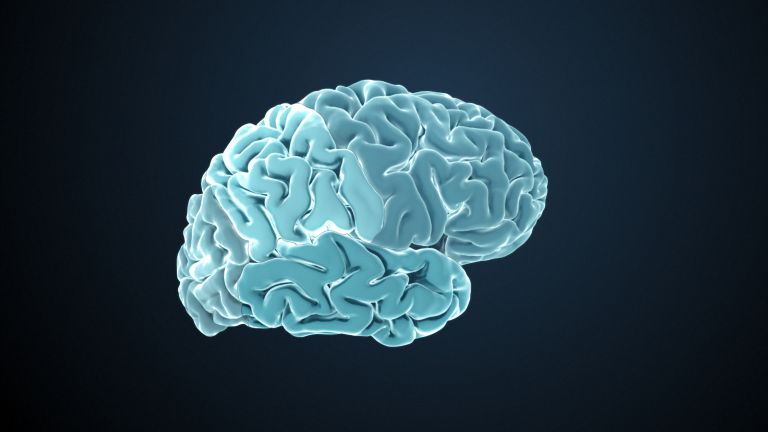

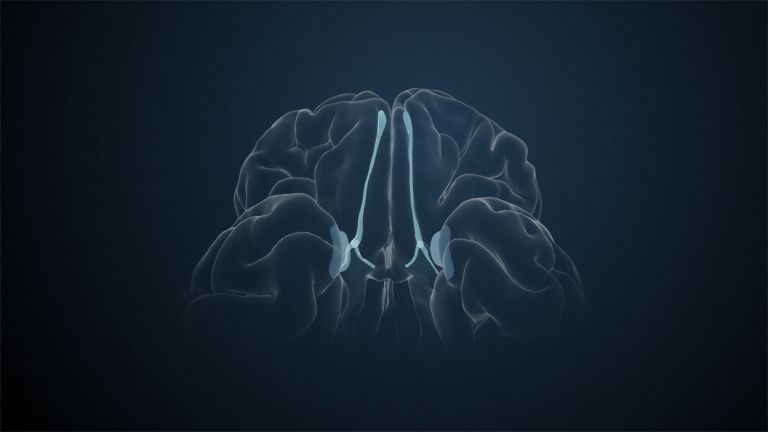

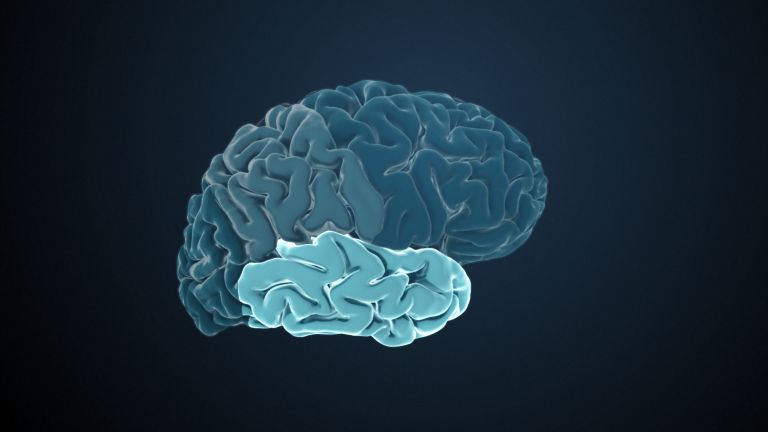

The temporal lobe merges into the parietal and occipital lobes towards the back of the head and the crown without any sharp boundaries. It is separated from the frontal lobe by a deep groove, the lateral fissure. The insula lies deep within this fissure. Looking at the brain from below, you can see that the two temporal lobes “frame” the brain stem. After all, their front, blunt pole is actually located at the rear edge of what is colloquially referred to as the temple.

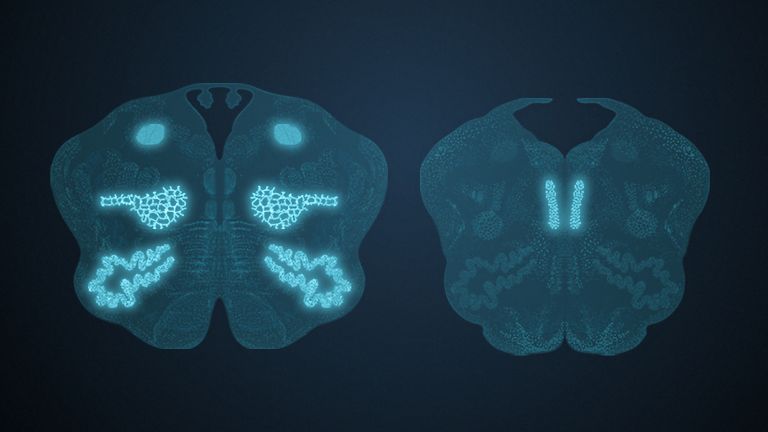

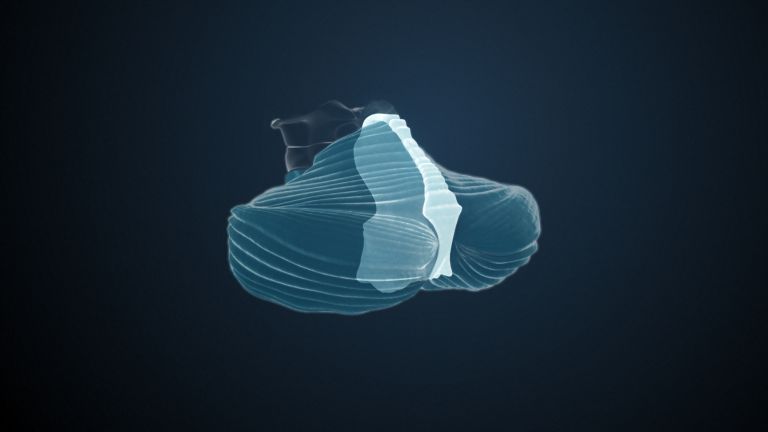

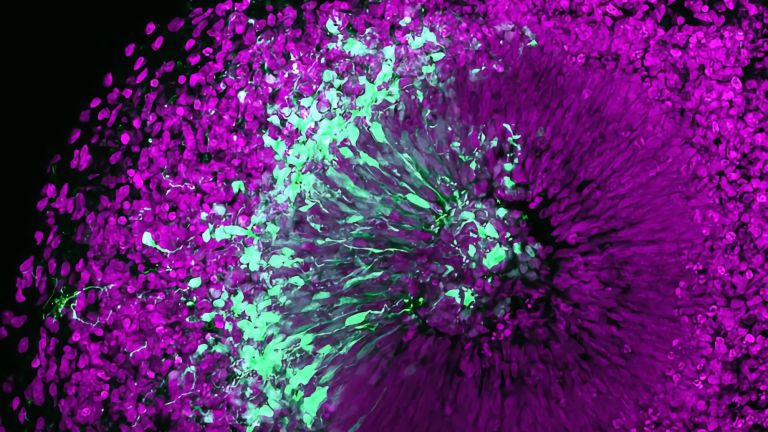

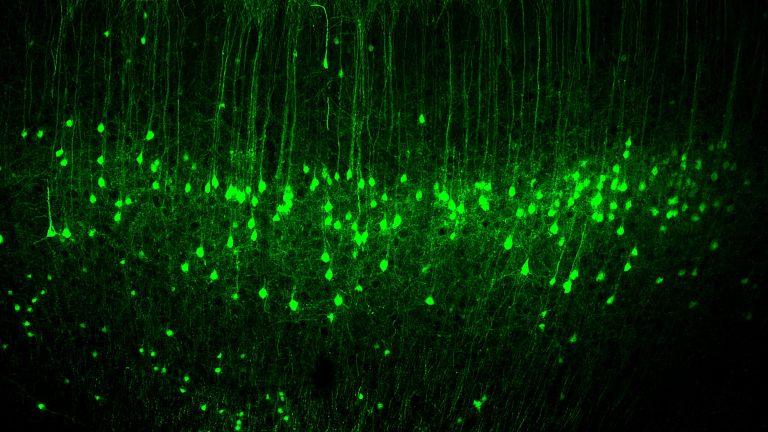

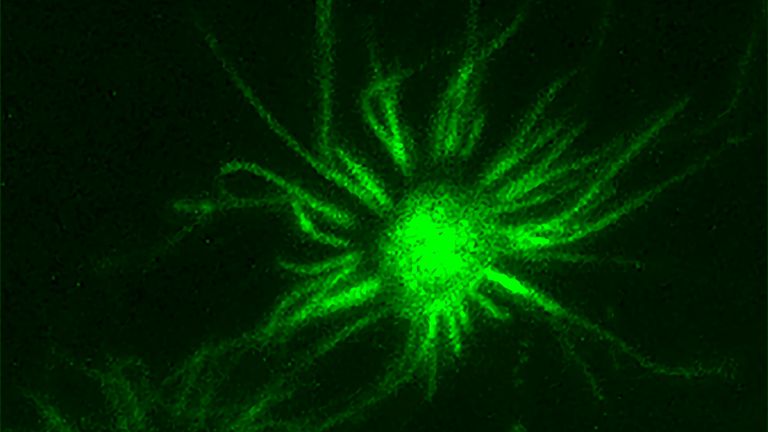

When viewed under a microscope, the temporal lobe reveals not only centers with the typical six-layer structure of the neocortex, but also numerous allocortical centers – i.e., “differently layered,” non-six-layer cortices. In addition, the temporal lobe is home to the amygdala, which consists of layered, and therefore cortical, and unlayered collections of nerve cells. Given this diversity, it is important to discuss the temporal lobe “piece by piece,” i.e., region by region.

Sound, image, and language

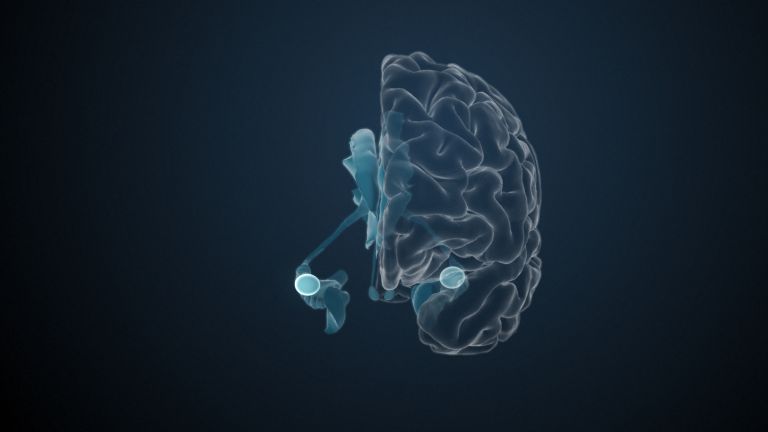

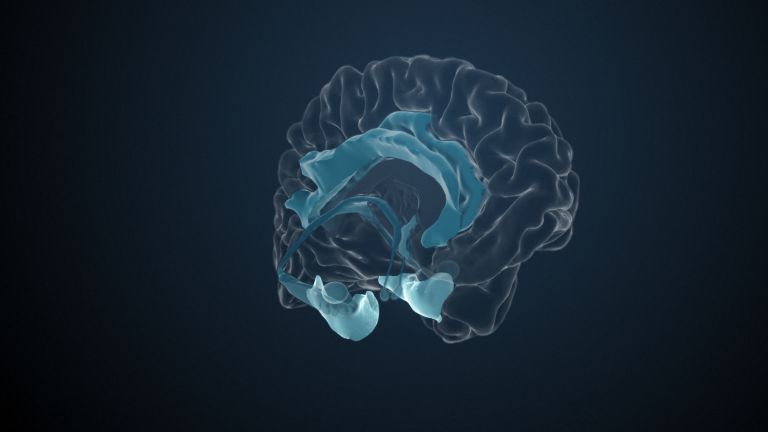

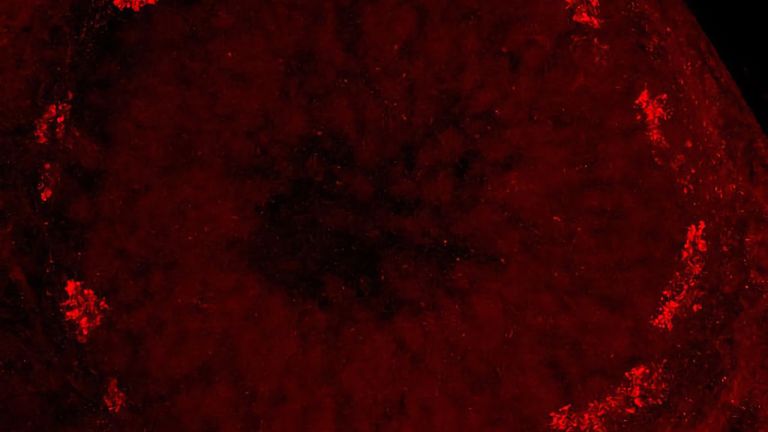

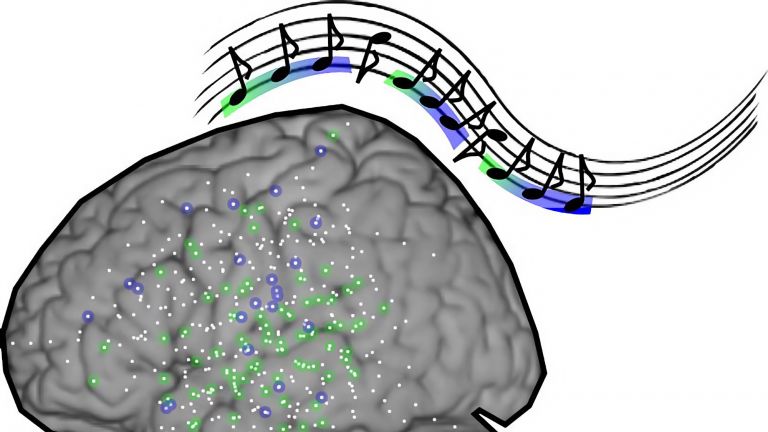

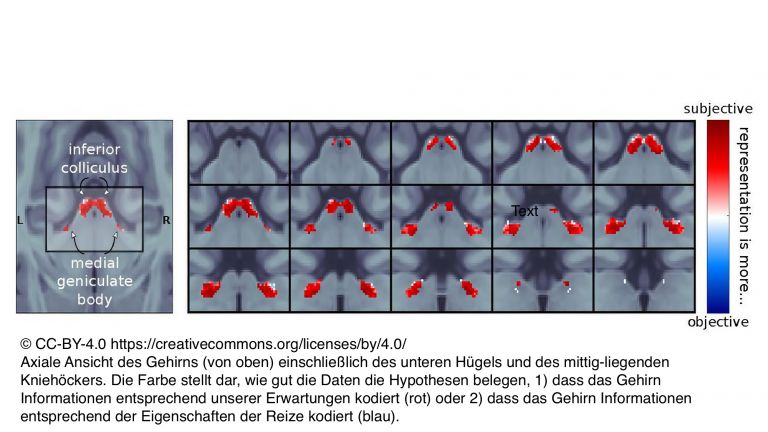

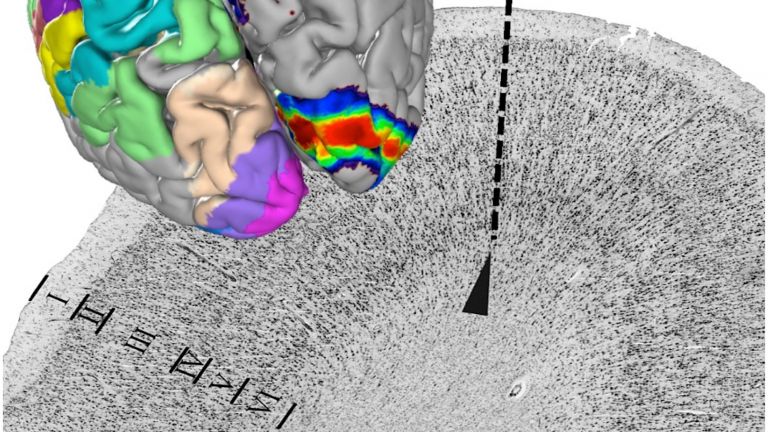

Perhaps the best-known function of the temporal lobe is hearing. Well-known, yes. Conspicuous, no. This is because the primary auditory center, the so-called Heschl's gyrus, is hidden in the deep lateral fissure. After several synaptic switches in the brain stem and thalamus, the auditory pathway, which transmits signals from the sensory cells in the cochlea of the ear, ends in these convolutions. The primary auditory center in Heschl's gyrus is only about the size of a postage stamp. The secondary and tertiary auditory centers downstream are much larger. They are located in the upper and middle gyrus of the temporal lobe and occupy almost the entire cortical surface of the temporal lobe, which can be seen in the side view. This makes hearing one of the most extensive systems in our cerebrum – speech and music apparently require a high level of “computational effort.”

Where the upper and middle temporal convolutions merge into the cortex of the occipital lobe – which is primarily responsible for the visual system – auditory and visual functions “overlap.” This is where the lexical centers involved in recognizing written and spoken words are located. Particularly well known is the sensory Wernicke's area, which is located in the dominant – usually left – hemisphere. A lesion in this area leads to disturbances in speech and writing comprehension.

Recommended articles

Scent and fear

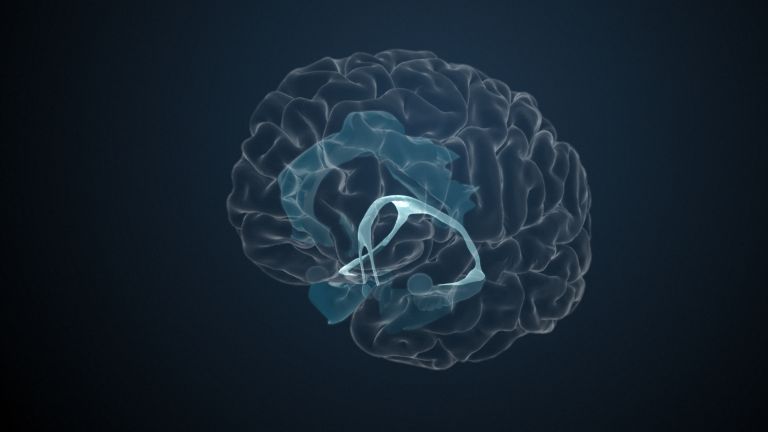

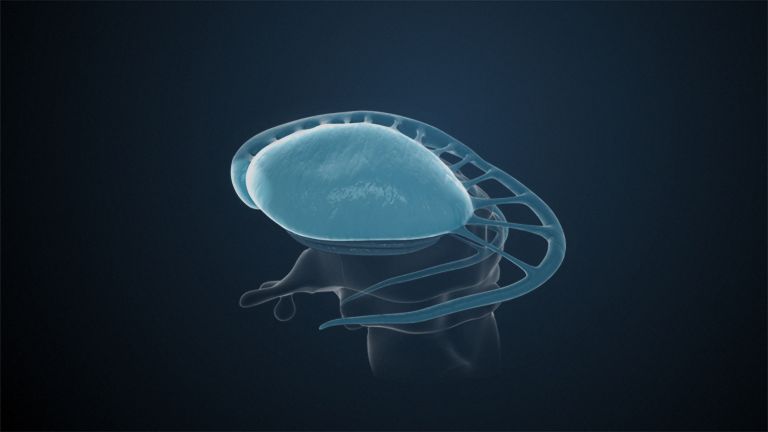

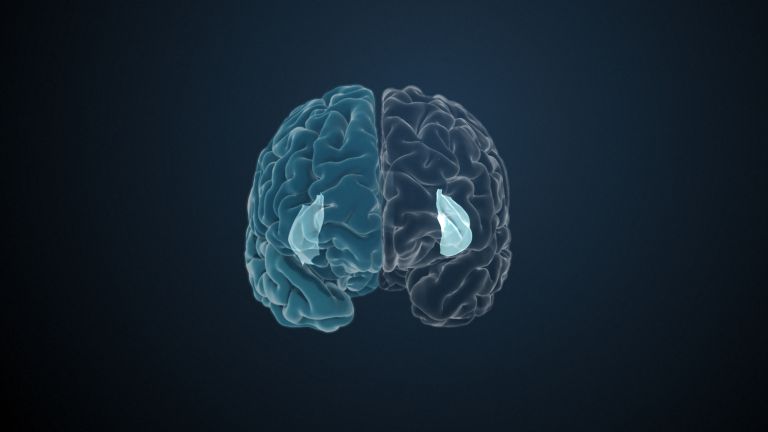

Looking at the temporal lobe from below, you will see a small inward bulge on its inner surface, just behind its blunt anterior pole. It is called the uncus, or hook. This hook is quite remarkable: the olfactory tract ends at its three-layered, allocortical surface. Just below these olfactory cortices, and even forming part of them, lies the amygdala, or almond-shaped nucleus. The amygdala belongs functionally to the limbic system and is responsible for the affective coloring of our experiences. However, it is predominantly dark colors – fear and terror – with which it paints our inner worlds.

Remembering and forgetting

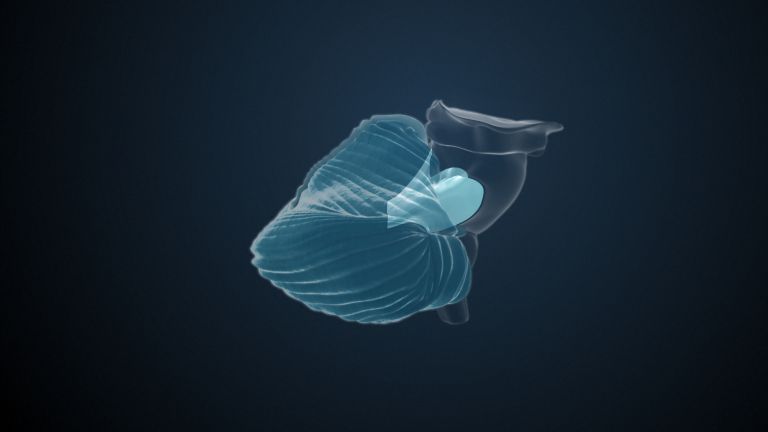

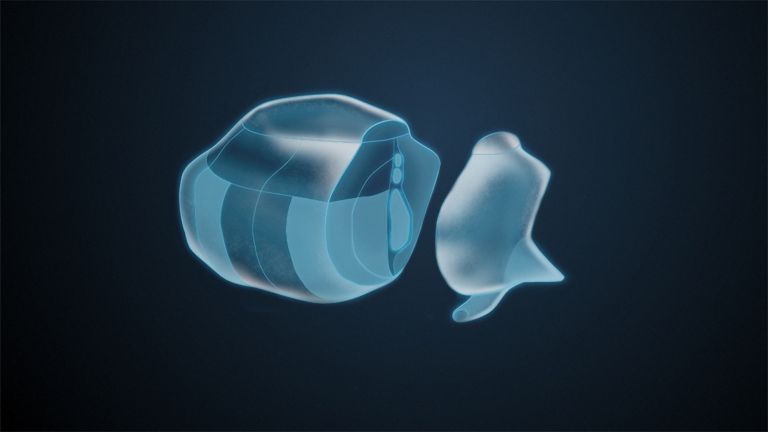

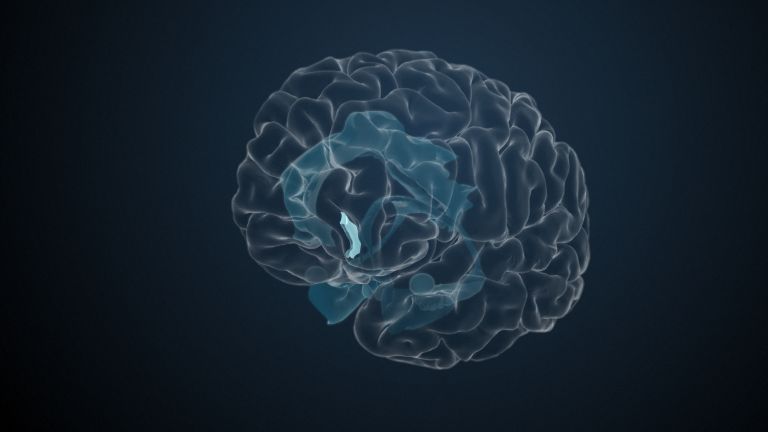

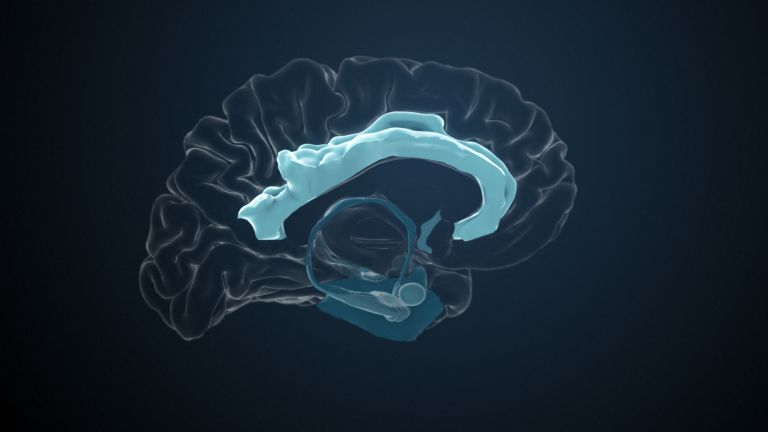

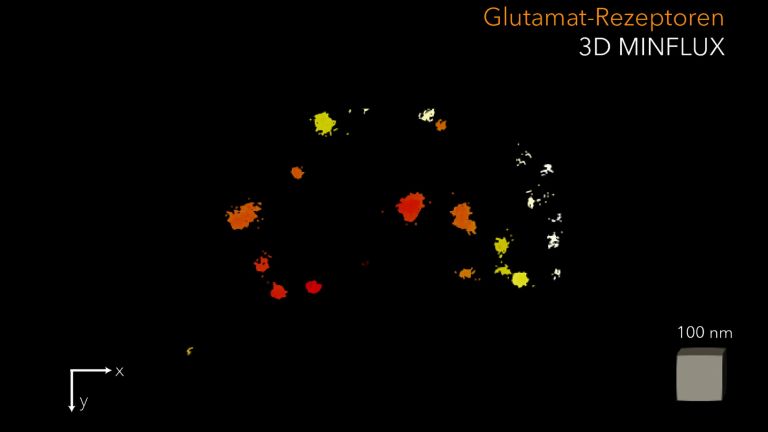

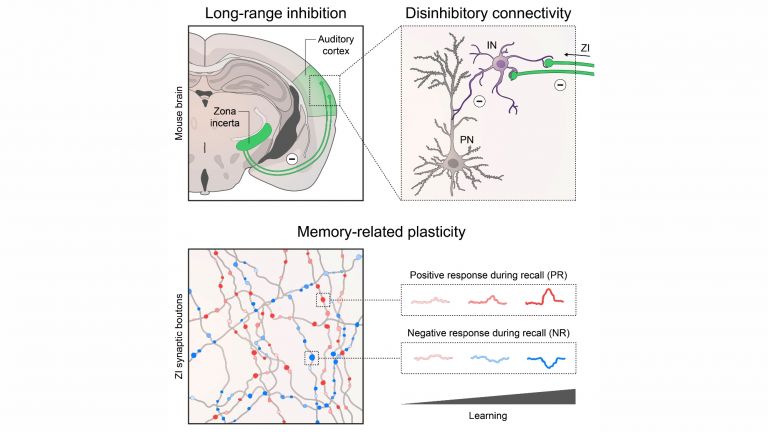

The temporal lobe also plays an important role in memory. And once again, it is the allocortical, i.e., non-typical six-layered cortical areas that serve these functions, and they too are considered part of the limbic system. The widest convolution of the temporal lobe, located furthest inside and visible from below, is the parahippocampal gyrus. It contains the entorhinal cortex, which acts as a kind of interface between what we are experiencing right now and the memory system. Right next to it and slightly above it is the hippocampal formation. To see it, you would have to cut off the temporal lobe and look at it from the inside. Together, these two – the hippocampal formation and the entorhinal cortex – are responsible for both “reading” new memory content and retrieving existing memories.

Memories are not limited to knowledge and biography. Rather, they enable us to orient ourselves in everyday life. Important interfaces between the visual system and memory are formed here by the isocortices on the posterior surface of the temporal lobe. For example, centers involved in the (re-)recognition of faces have been found in the spindle-shaped gyrus fusiformis.

Although we know a lot about the temporal lobe, it is still largely unclear what happens in the other isocortical regions, especially at its blunt anterior pole.

First published on September 5, 2011

Last updated on November 28, 2025