The Pituitary Gland

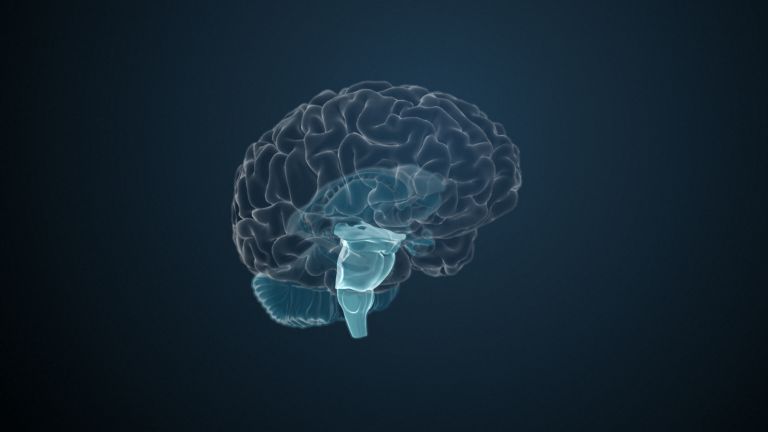

The pituitary gland is actually located at the base of the brain. It was once thought to produce nasal mucus. However, we now know its true function: as an endocrine organ, it regulates homeostatic processes that are essential for survival. This makes it the queen of hormone-producing glands.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Horst-Werner Korf

Published: 21.03.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

The pituitary gland, which is only the size of a bean, hangs at the bottom of the brain. The hormones that are partly produced and partly released in it maintain the balance, or homeostasis, of metabolic processes.

Hypophysis

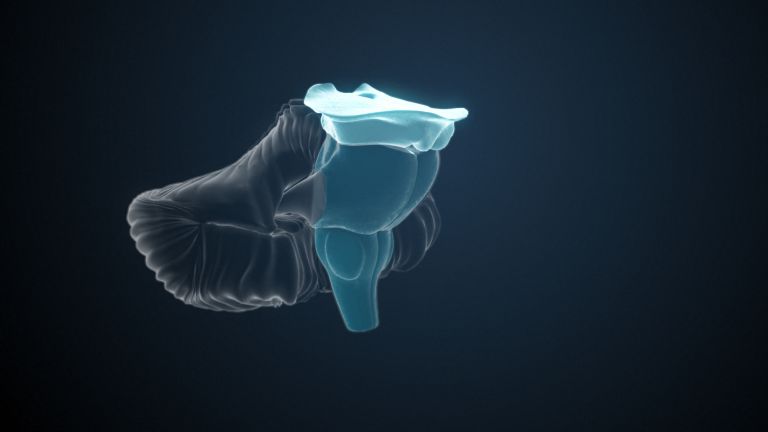

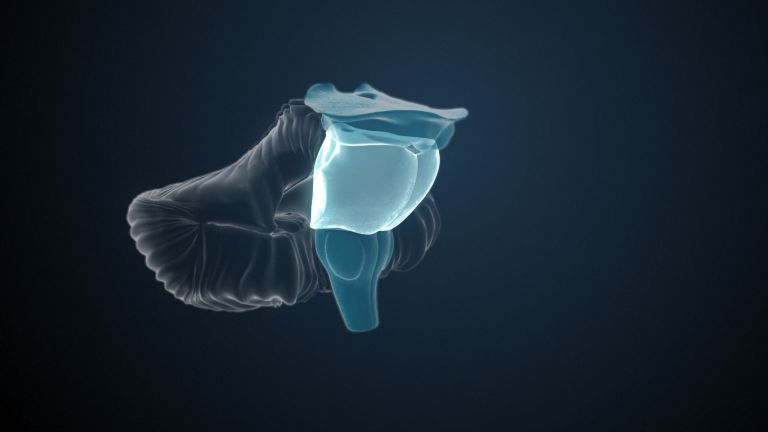

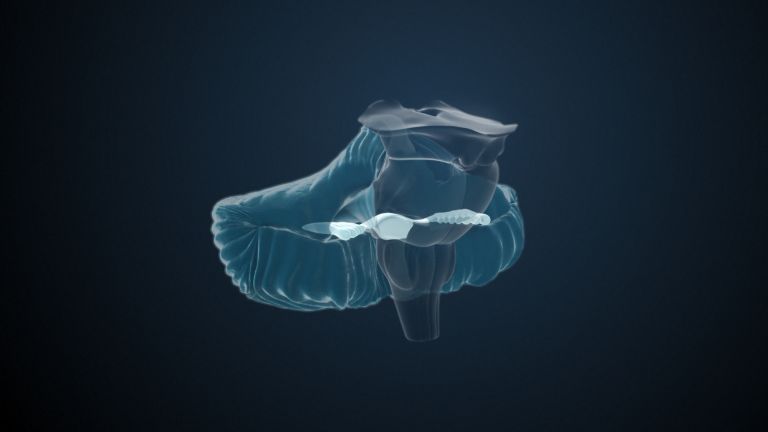

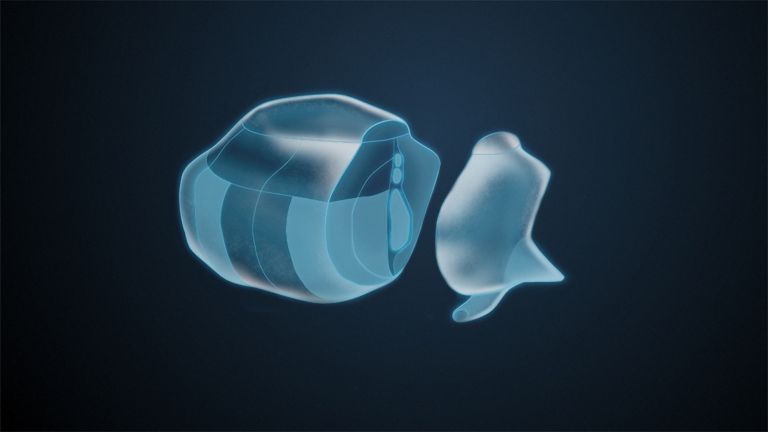

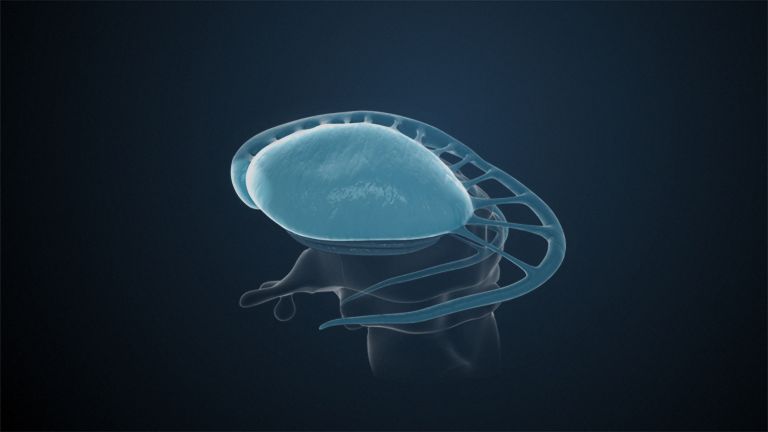

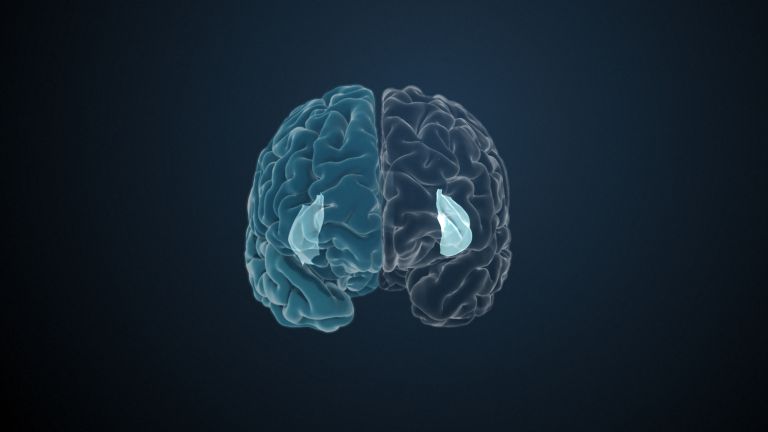

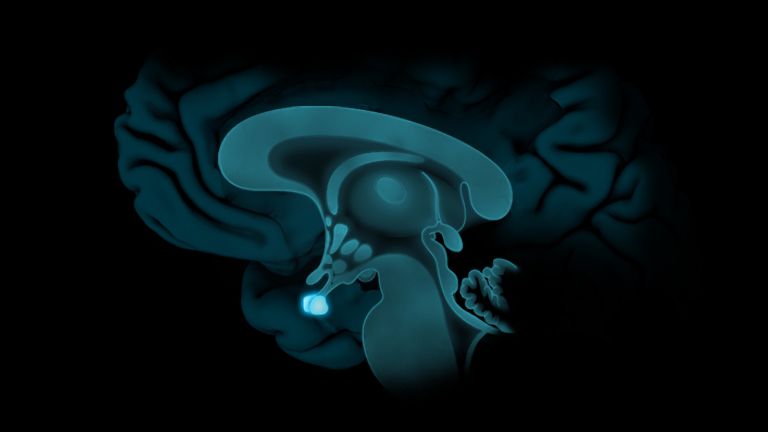

The pituitary gland is an important hormone gland in the body. It hangs like a drop below the hypothalamus and is no larger than a pea. The pituitary gland consists of two parts, the anterior lobe (adenohypophysis) and the posterior lobe (neurohypophysis). The anterior lobe of the pituitary gland has the special property of being partially exempt from the blood-brain barrier, allowing it to release hormones directly into the blood.

Divided into two parts in form and function

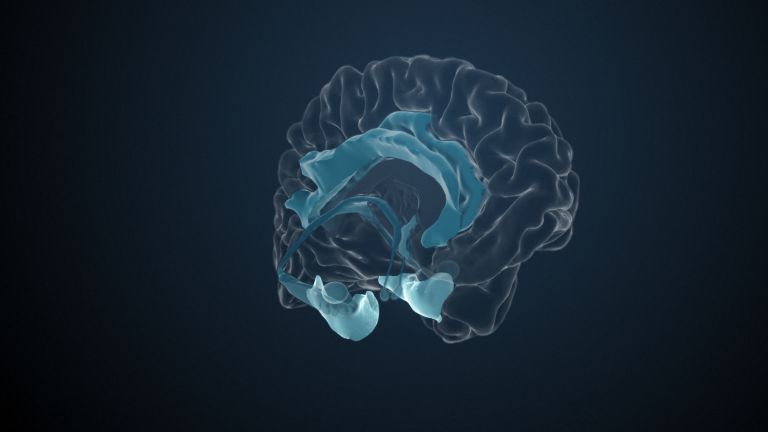

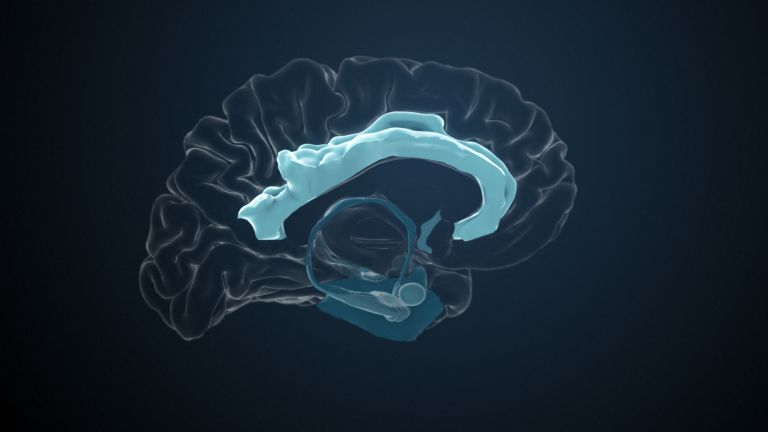

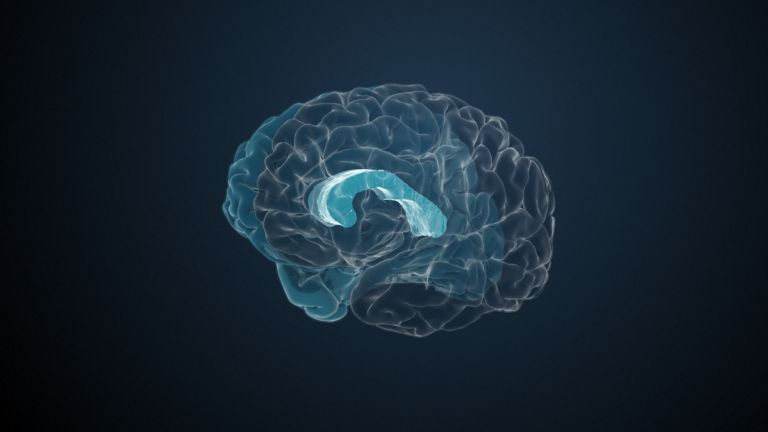

The pituitary gland hangs from a delicate, hollow stalk barely a millimeter thick – the pituitary stalk or infundibulum – at the base of the Diencephalon. The gland itself is about the size of a bean. It lies in a bony cavity in the center of the skull, which is called the sella turcica because of its resemblance to old-fashioned wooden horse saddles. The glandular body of the pituitary gland consists of two parts – the anterior lobe (lobus anterior), which is further subdivided, and the largely homogeneous posterior lobe (lobus posterior).

Diencephalon

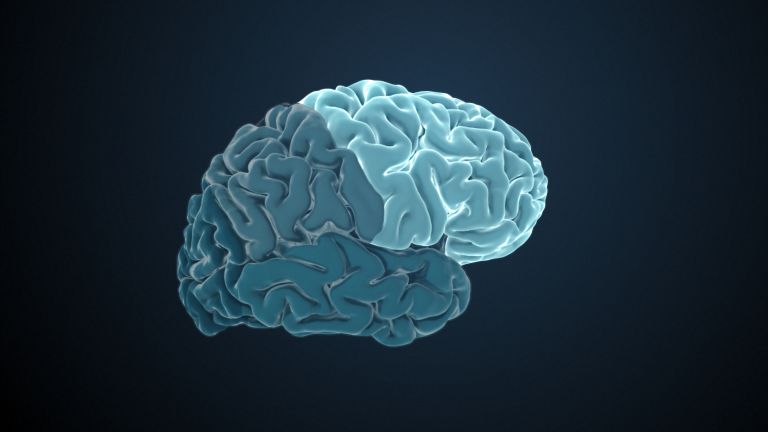

The diencephalon (midbrain) includes the thalamus and hypothalamus, among other structures. Together with the cerebrum, it forms the forebrain. The diencephalon contains centers for sensory perception, emotion, and the control of vital functions such as hunger and thirst.

posterior

A positional term – posterior means "towards the back, located at the rear." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction towards the tail.

Recommended articles

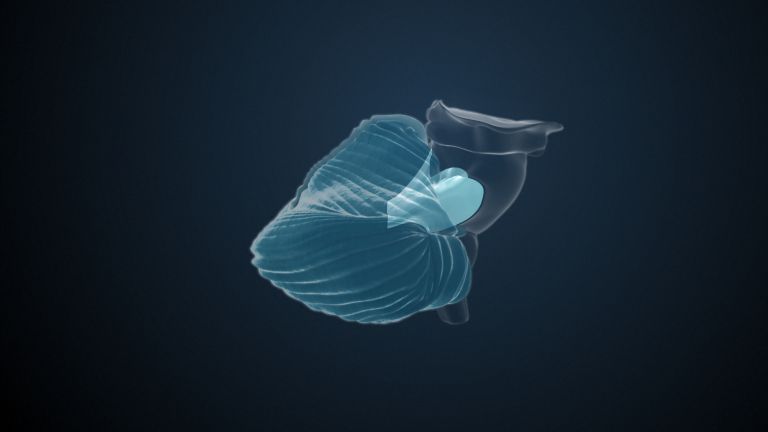

One part brain

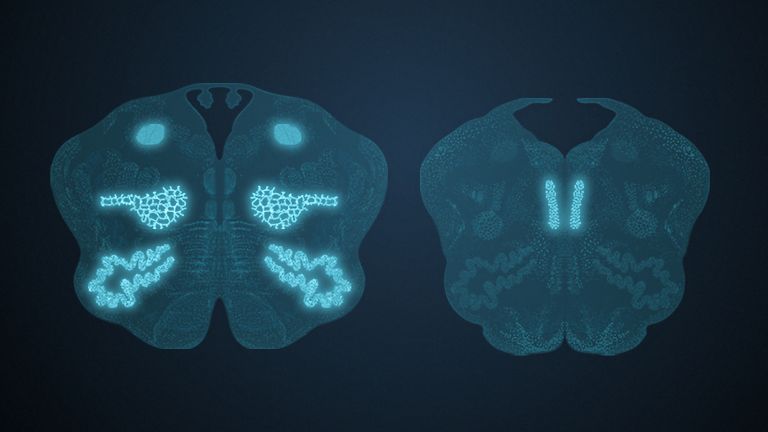

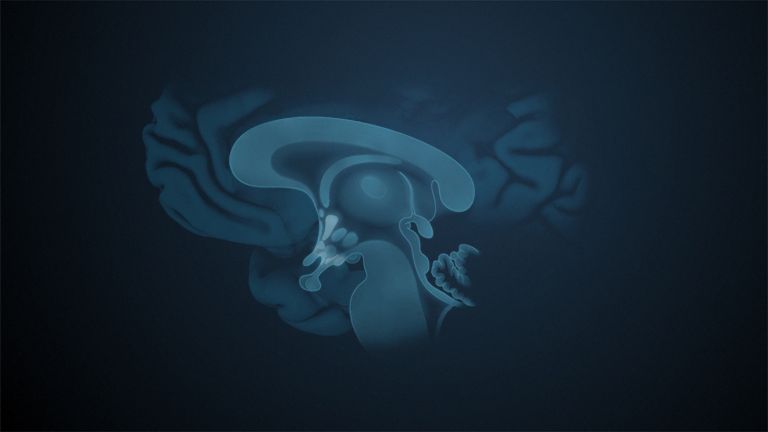

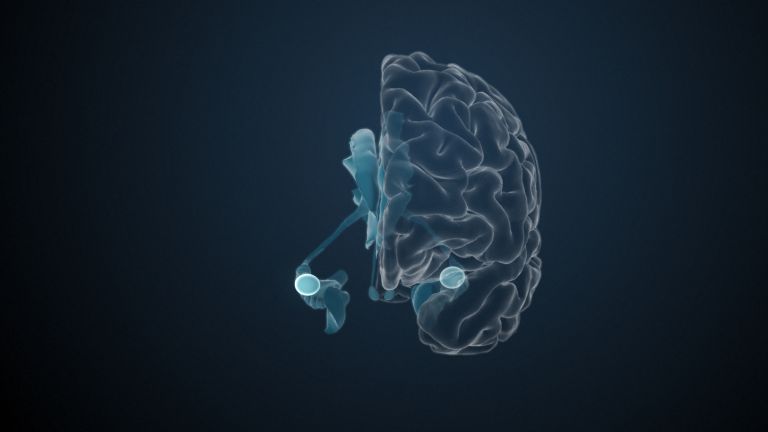

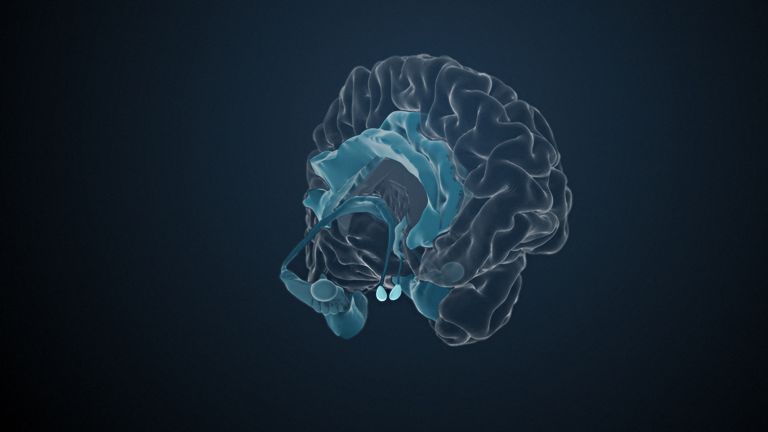

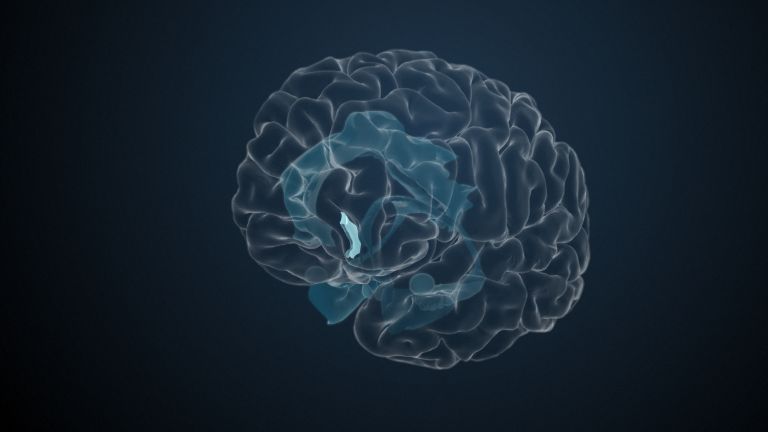

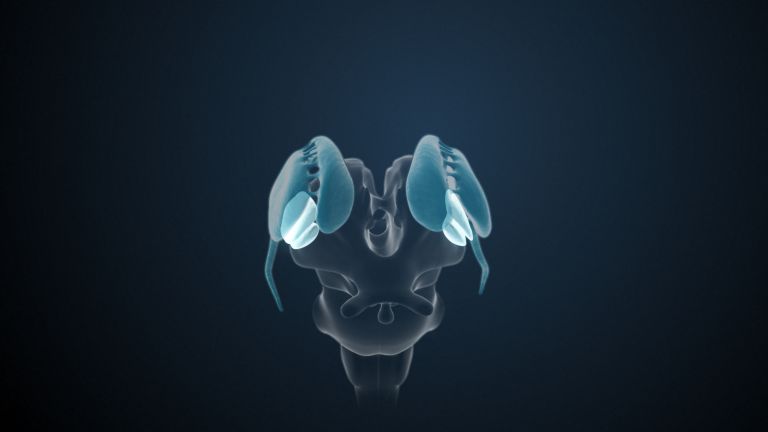

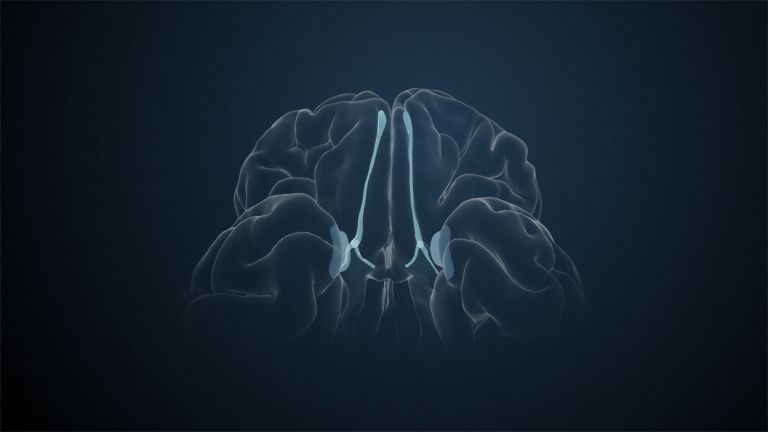

The posterior lobe, also known as the neurohypophysis, is part of the brain. It is here that the thin pituitary stalk, which originates in the diencephalon, continues. Axons from glandular nerve cells run through this pituitary stalk, whose large cell bodies are located in the anterior hypothalamus, in the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei (magnocellular Hypothalamus). Along these nerve fibers, the hormones produced by the glandular nerve cells reach the Neurohypophysis (axonal transport), where they are released into the bloodstream.

The glandular nerve cells produce two hormones: the antidiuretic Hormone (ADH) and oxytocin. ADH regulates kidney function and thus water balance. Oxytocin has a variety of functions, most of which are related to reproduction: it causes the uterus to contract during childbirth and milk to be released into the breast, but it is also released during orgasm in both sexes. It is also said to have significant psychogenic effects. It makes us inclined to be affectionate and influences bonding behavior.

posterior

A positional term – posterior means "towards the back, located at the rear." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction towards the tail.

Hypothalamus

The hypothalamus is considered the center of the autonomic nervous system, meaning it controls many motivational states and regulates vegetative aspects such as hunger, thirst, and sexual behavior. As an endocrine gland (which, unlike an exocrine gland, releases its hormones directly into the blood without a duct), it produces numerous hormones, some of which inhibit or stimulate the pituitary gland to release hormones into the blood.In this function, it also plays an important role in the response to pain and is involved in pain modulation.

Neurohypophysis

The neurohypophysis is the posterior lobe of the pituitary gland. It stores the hormones oxytocin and vasopressin, which are produced in the hypothalamus, and releases them into the bloodstream when needed.

Hormone

Hormones are chemical messengers in the body. They serve to transmit information between organs and cells, usually slowly, e.g., to regulate blood sugar levels. Many hormones are produced in glandular cells and released into the blood. At their destination, e.g., an organ, they dock at binding sites and trigger processes inside the cell. Hormones have a broader effect than neurotransmitters; they can influence various functions in many cells of the body.

oxytocin

Oxytocin

Oxytocin is a hormone produced in the paraventricular nucleus and supraoptic nucleus of the hypothalamus and released into the blood via the posterior lobe of the pituitary gland. It initiates contractions during childbirth and supports the milk ejection reflex during breastfeeding. It is also released during orgasm. Oxytocin can promote trust and strengthen pair bonding, but recent findings show that its effects are more complex and, in certain contexts, can also promote separation from out-groups.

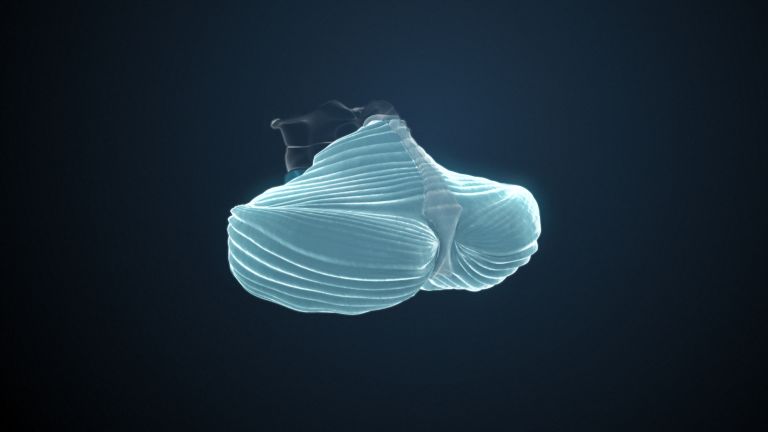

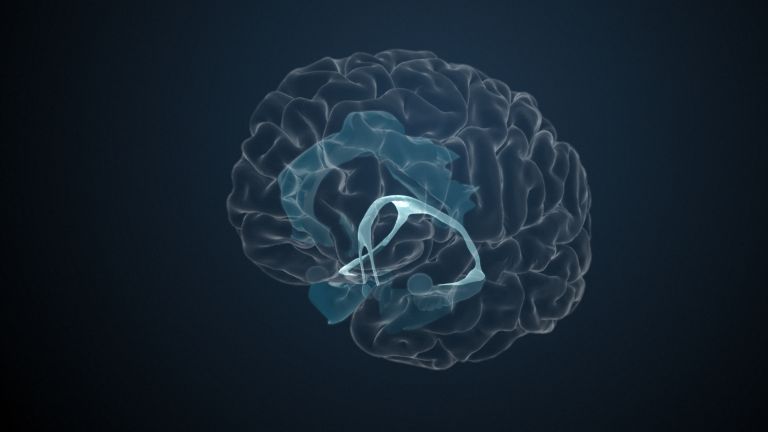

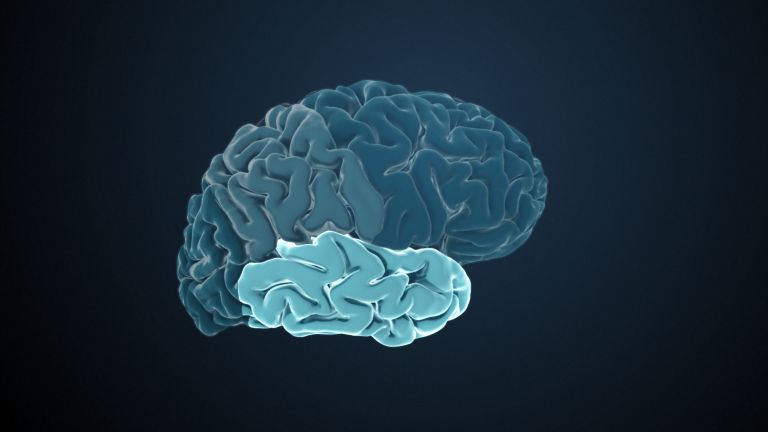

One part throat

The Anterior pituitary gland, also known as the adenohypophysis, is not part of the brain, but grows towards the Neurohypophysis from the roof of the throat below. Originally – in evolutionary history – it was a gland associated with the digestive system that was “converted” into an endocrine gland.

The vast majority of the anterior lobe, the pars distalis, consists of small clusters of glandular cells surrounded by numerous blood vessels. The glandular cells produce a variety of hormones that either control other endocrine glands in the body (glandotropic hormones) or directly affect non-endocrine cells (bones/muscles/liver), known as effect hormones. This second group includes somatropin, which acts on bones and controls body growth, among other things, and prolactin, which stimulates growth and milk production in the mammary gland. Glandotropic hormones include thyroid-stimulating Hormone (TSH), which controls the thyroid gland, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), both of which act on endocrine cells in the testicles and ovaries, and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which regulates the function of the adrenal cortex.

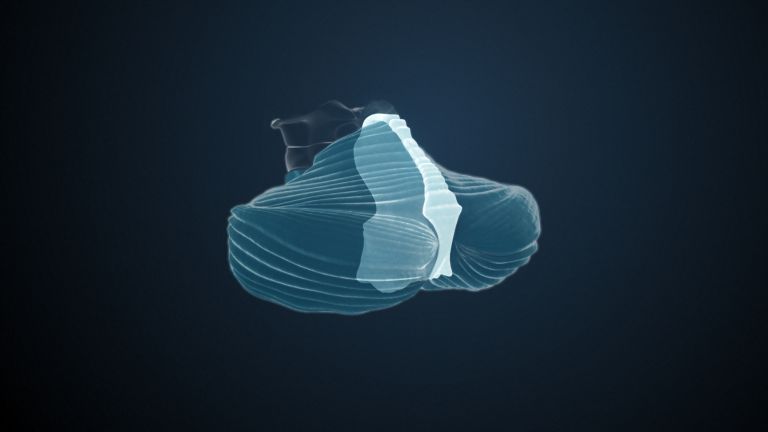

And who controls the controllers? This task falls to the brain. In the hypothalamus, near the attachment point of the pituitary stalk, there are other relatively small glandular nerve cells that form the Parvocellular Hypothalamus and control the activity of the endocrine cells of the pars distalis through so-called releasing and Inhibiting hormones In order to transport these hormones from the hypothalamus specifically to the pars distalis, there is a specialized vascular system at the upper end of the pituitary stalk, in the eminentia mediana, called the portal circulation of the pituitary gland. This is used to supply the releasing and inhibiting hormones to the anterior pituitary gland.

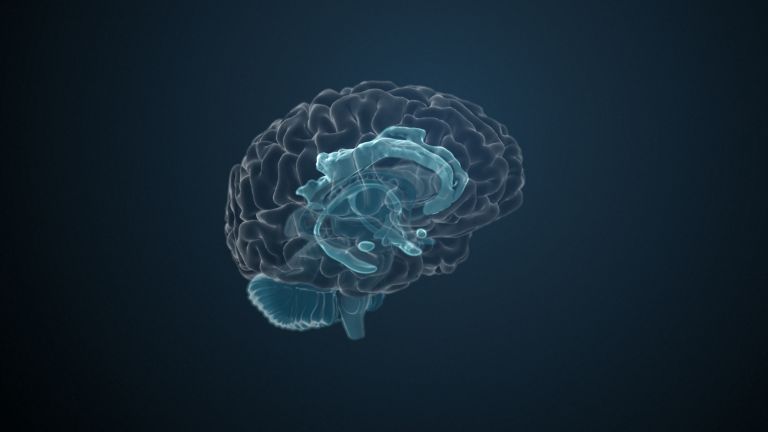

The pars intermedia of the anterior lobe is a thin, leaf-like piece of tissue on the posterior surface of the pars distalis, which separates it from the neurohypophysis. Unlike the pars distalis, the pars intermedia is almost completely devoid of blood vessels. Unlike the other sections of the pituitary gland, it contains small glandular follicles: tiny vesicles surrounded by glandular cells that produce Endorphins and melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH).

The pars tuberalis is a small, finger-shaped extension of the anterior lobe that faces the brain and attaches to the pituitary stalk. Similar to a cell population in the pars distalis, the pars tuberalis also produces TSH, whose release is controlled not by thyroid-stimulating hormone (TRF) (a Releasing hormone from the parvocellular hypothalamus) but by melatonin, the hormone of the Epiphysis. Therefore, the pars tuberalis is extremely densely populated with receptors for Melatonin. The pars tuberalis controls seasonal processes, i.e., processes that depend on the time of year.

The function of the pars tuberalis is particularly evident in animals: here, it controls seasonal reproductive behavior by sending TSH signals to the hypothalamus, causing the release of the releasing hormones for FSH and LH from the pars distalis. The pars tuberalis also produces endocannabinoids, which may be involved in controlling prolactin release from the pars distalis. However, the function of the endocannabinoids of the pars tuberalis needs to be investigated further.

Anterior pituitary

The adenohypophysis is a gland and is also referred to as the "anterior pituitary gland." The adenohypophysis produces hormones such as prolactin and releases them directly into the blood, meaning it is endocrine. It is therefore involved in regulating numerous physiological processes. Together with the neurohypophysis, which is part of the brain, it forms the pituitary gland. The two systems are closely linked via a contact surface.

Neurohypophysis

The neurohypophysis is the posterior lobe of the pituitary gland. It stores the hormones oxytocin and vasopressin, which are produced in the hypothalamus, and releases them into the bloodstream when needed.

Hormone

Hormones are chemical messengers in the body. They serve to transmit information between organs and cells, usually slowly, e.g., to regulate blood sugar levels. Many hormones are produced in glandular cells and released into the blood. At their destination, e.g., an organ, they dock at binding sites and trigger processes inside the cell. Hormones have a broader effect than neurotransmitters; they can influence various functions in many cells of the body.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Parvocellular

"Parvus" means "small." In the lateral geniculate nucleus, the switching station for visual stimuli in the thalamus, the outer four layers are called parvocellular because, unlike the magnocellular cell layers, they have small cell bodies. The parvocellular system transmits information for the perception of color and fine details.

Hypothalamus

The hypothalamus is considered the center of the autonomic nervous system, meaning it controls many motivational states and regulates vegetative aspects such as hunger, thirst, and sexual behavior. As an endocrine gland (which, unlike an exocrine gland, releases its hormones directly into the blood without a duct), it produces numerous hormones, some of which inhibit or stimulate the pituitary gland to release hormones into the blood.In this function, it also plays an important role in the response to pain and is involved in pain modulation.

Inhibiting hormones

Hormones produced in the hypothalamus that inhibit the release of other hormones from the adenohypophysis (part of the pituitary gland).

vascular

The term refers to vessels in the body in which fluids such as blood or lymph circulate. In a narrower sense, doctors refer to the network of veins, arteries, and capillaries as the "vascular system." If the vascular system is blocked, for example as a result of a stroke, less blood reaches the brain. This means that it receives less oxygen and other nutrients. This can lead to impaired cognitive functions and the development of "vascular dementia." After degenerative forms of dementia such as Alzheimer's, vascular dementia is the second most common form of this group of diseases.

posterior

A positional term – posterior means "towards the back, located at the rear." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction towards the tail.

Endorphins

Abbreviation for endogenous morphines, i.e., morphines produced by the body itself. They play an important role in suppressing and alleviating pain. They are also involved in euphoria (feelings of elation).

Releasing hormone

Hormones of the hypothalamus that promote the release of other hormones in the adenohypophysis.

Epiphysis

glandula pinalis/pineal gland

The epiphysis (pineal gland) is an unpaired component of the epithalamus (part of the diencephalon). It is a gland that secretes melatonin. Among other things, the epiphysis controls the "internal clock."

Melatonin

Melatonin is a hormone released by the pineal gland in the brain when it is dark. Melatonin levels are highest at night and then decrease throughout the day. This makes it an important messenger substance for the "internal clock" and it appears to play a particularly important role in regulating sleep.

First published on August 23, 2011

Last updated on March 21, 2025