Smell & Taste

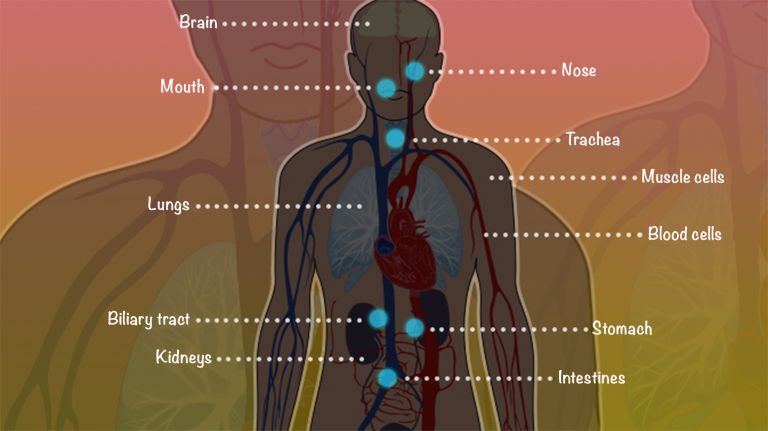

Chemoreceptors are nothing special: even single-celled organisms use them to explore their environment. But just as a single note does not make music and a scale does not make a symphony, it is only through the interaction of many sensory modalities that humans can have an experience worthy of five stars in the Michelin Guide.

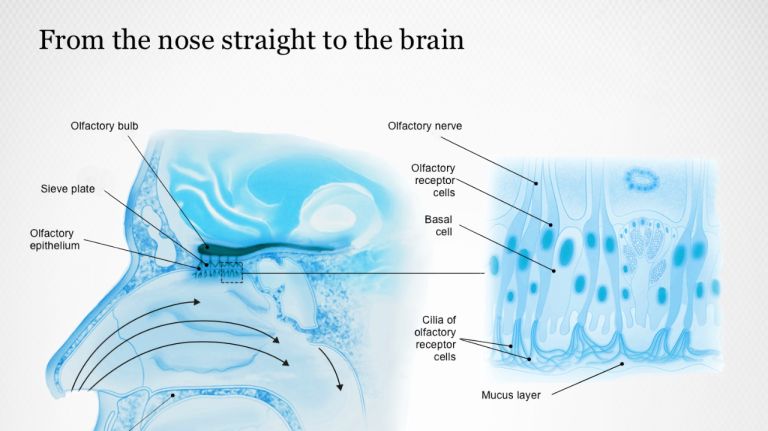

Our tongue can only Taste sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami. Umami is a tongue stimulus that indicates the presence of protein. It was the last of the five tastes to be discovered. Our nose, on the other hand, has 350 types of receptors that enable us to distinguish between thousands of smells. That is fewer than dogs or mice, but it is perfectly adequate for everyday life, in which we never perceive smell and taste stimuli in isolation, but always as a concert.

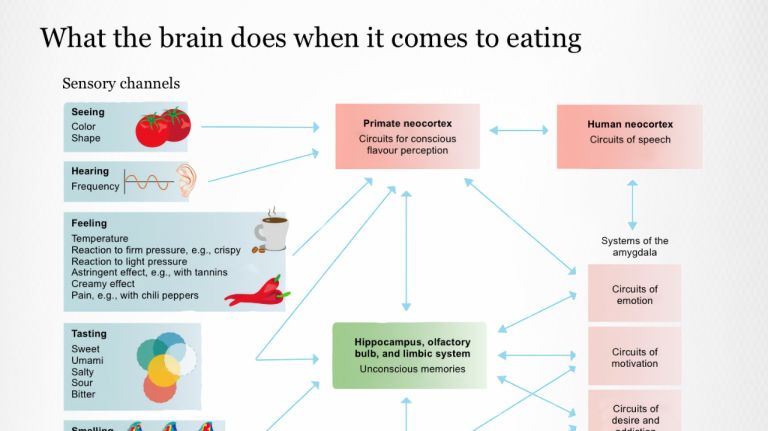

A concert in which sensory impressions play first fiddle, but which would not sound harmonious without feelings, thoughts, and, above all, memories. When the scent of fresh pine needles fills your Nose in December or a hint of sunscreen in July, your brain instantly generates a whole world.

Unpleasant smells and tastes have other, more short-term consequences. But whenever they activate our vomiting center, they may have saved our lives.

Smell and taste – often underestimated. An introduction.

Taste

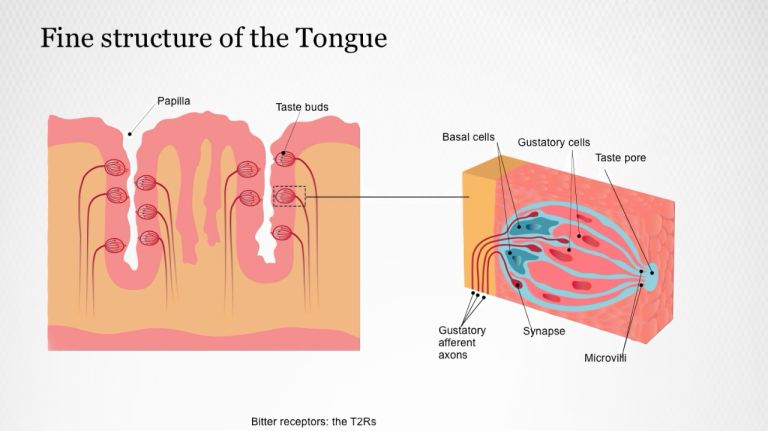

The sensory impression we refer to as "taste" results from the interaction between our senses of smell and taste. In terms of sensory physiology, however, "taste" is limited to the impression conveyed to us by the taste receptors on the tongue and in the surrounding mucous membranes. It is currently assumed that there are five different types of taste receptors that specialize in the taste qualities sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami. In 2005, scientists also identified possible taste receptors for fat, whose role as a distinct taste quality is still being investigated.

Nose

nasus

The olfactory organ of vertebrates. In the nasal cavity, the air is cleaned by cilia, and in the upper area is the olfactory epithelium, which detects odors.