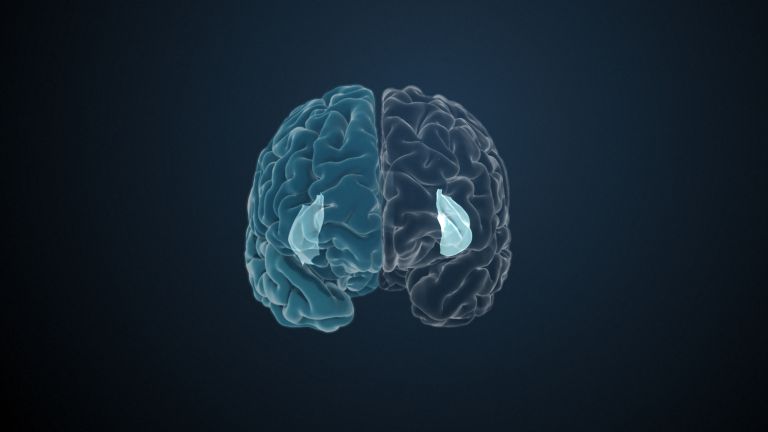

The Hippocampus

Does it really look like a seahorse? You can argue about its appearance, but not about its function: the hippocampus plays a crucial role in storing new memories – without it, you can't remember anything new.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Horst-Werner Korf

Published: 23.08.2011

Difficulty: serious

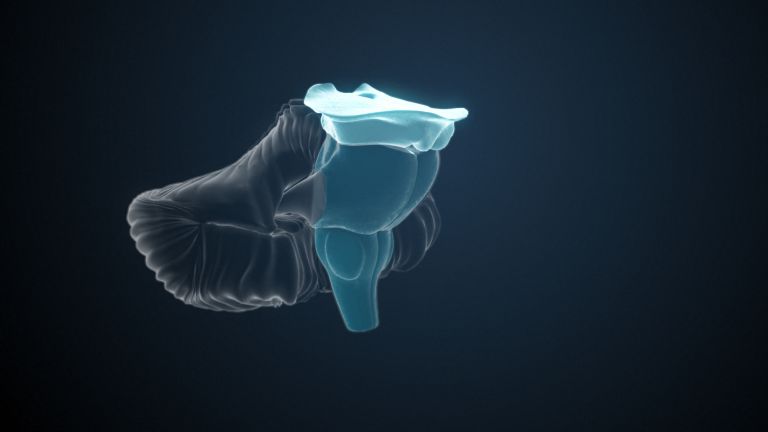

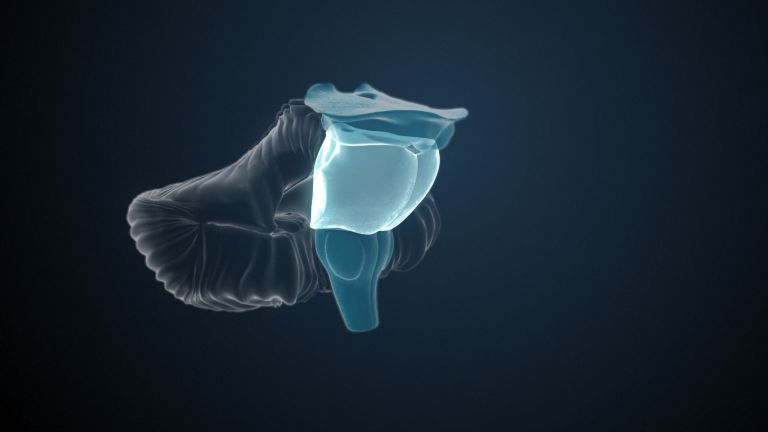

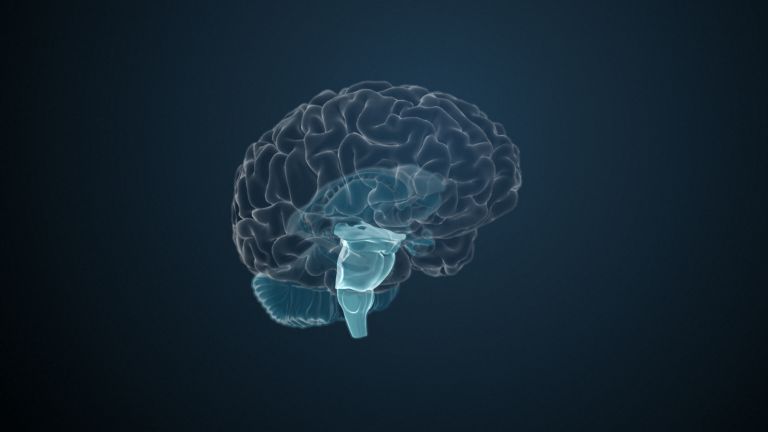

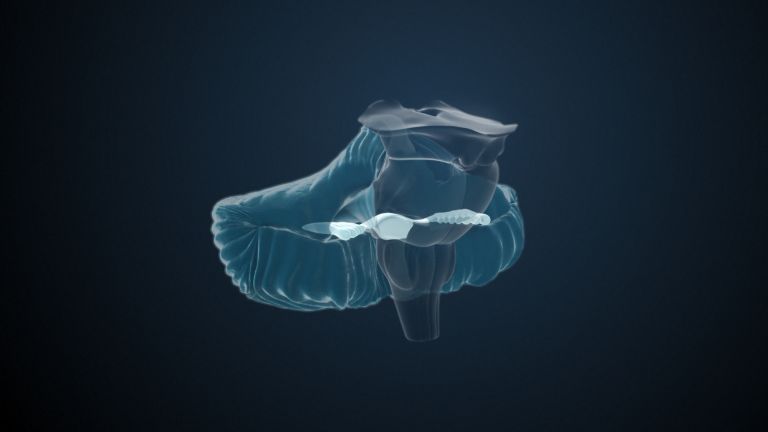

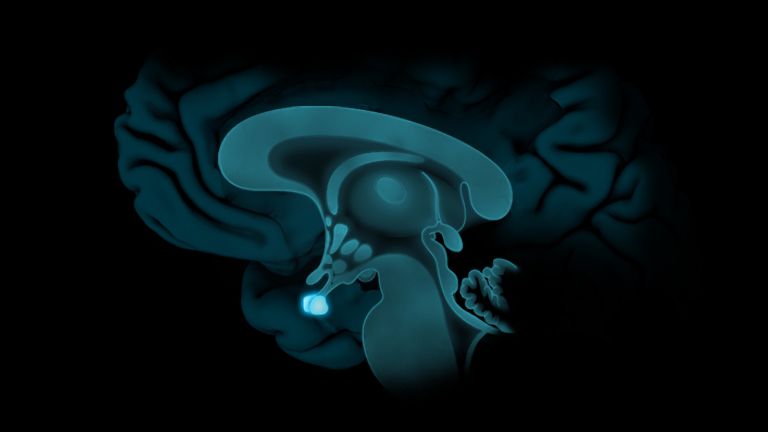

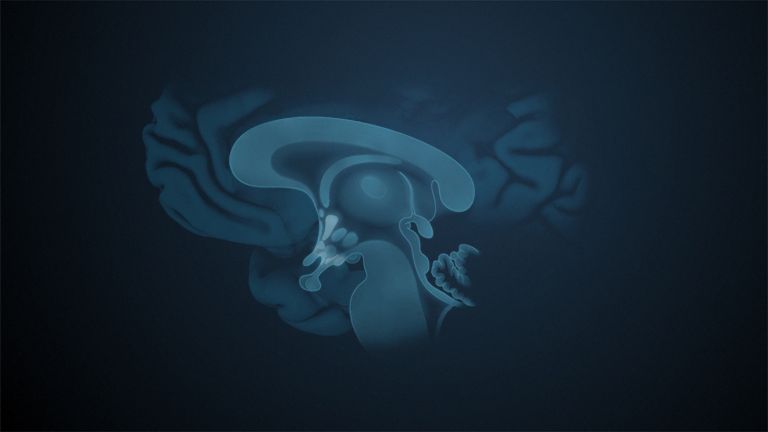

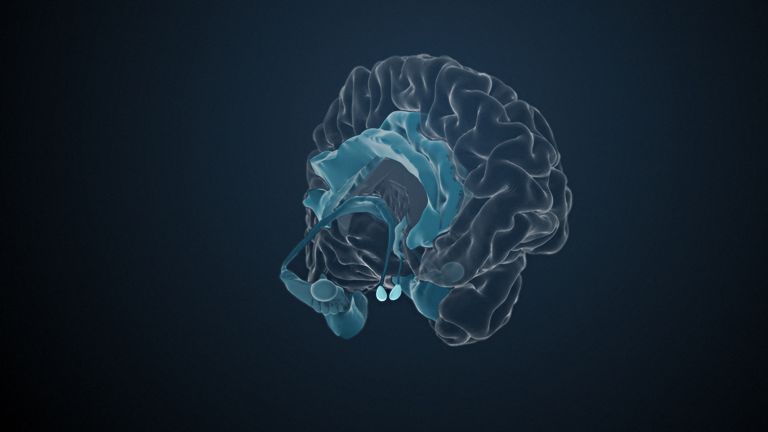

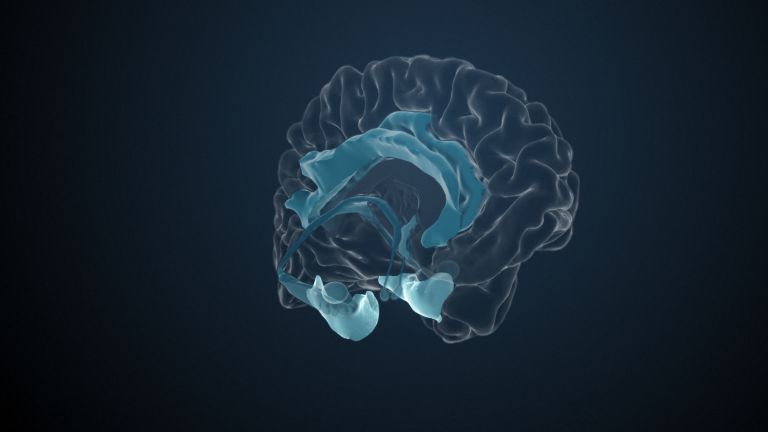

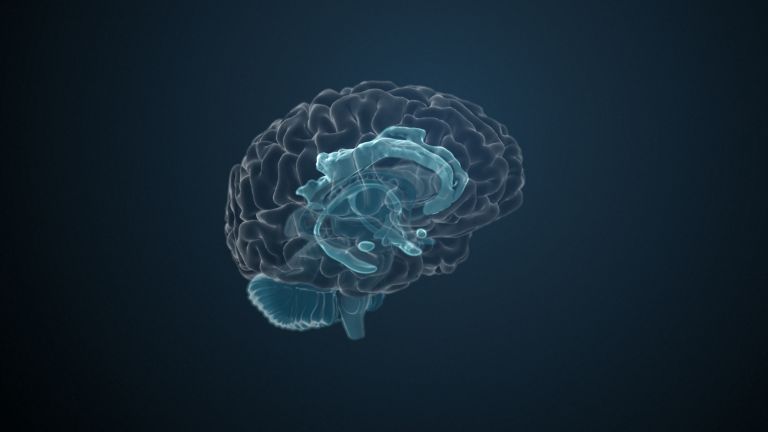

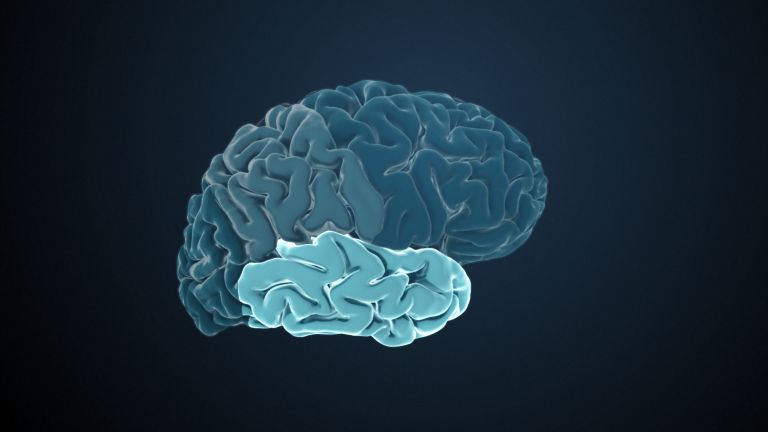

The Hippocampus is a “curled” piece of Cortex that lies inside the Temporal lobe at the base of the lateral ventricles, not unlike a worm. It is part of the limbic system, which is involved in the “creation,” “archiving,” and “retrieval” of content from Long-term memory It is also one of the few places in the brain where new nerve cells are born throughout our lives.

Hippocampus

The hippocampus is the largest part of the archicortex and an area in the temporal lobe. It is also an important part of the limbic system. Functionally, it is involved in memory processes, but also in spatial orientation and learning. It comprises the subiculum, the dentate gyrus, and the Ammon's horn with its four fields CA1-CA4.

Changes in the structure of the hippocampus due to stress are associated with chronic pain. The hippocampus also plays an important role in the amplification of pain through anxiety.

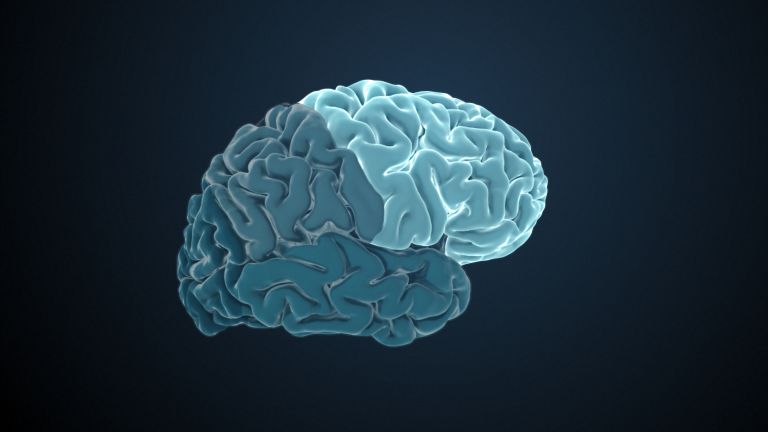

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Temporal lobe

Lobus temporalis

The temporal lobe is one of the four lobes of the cerebrum and is located laterally (on the side) at the bottom. It contains important areas such as the auditory cortex and parts of Wernicke's area, as well as areas for higher visual processing; deep within it lies the medial temporal lobe with structures such as the hippocampus.

lateral

A positional term – lateral means "towards the side." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction at right angles to the neural axis, i.e., to the right or left.

Long-term memory

Long-term memory stores information about events, facts, or skills over long periods of time, often for a lifetime. Different types of memory are stored in different areas of the brain. The cellular basis for these learning processes is based, among other things, on improved communication between two cells and is called long-term potentiation.

Fish and mythical creature

The “hippocamp” is a mythical creature from Greek mythology: the front part of a horse, but with the torso and tail of a fish. The hippocampi were the mount and draft of various sea gods. The real-life seahorses are named after them. Or the hippocampi are named after them, no one knows.

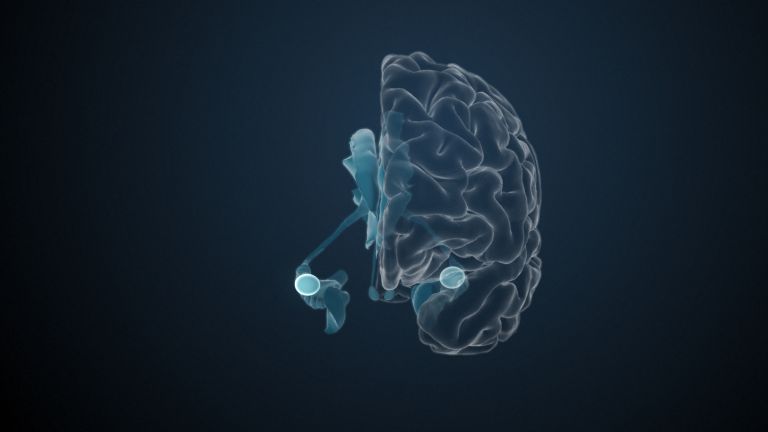

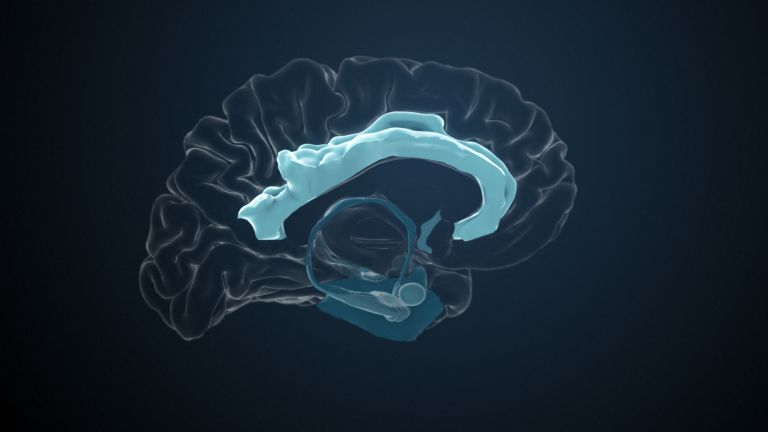

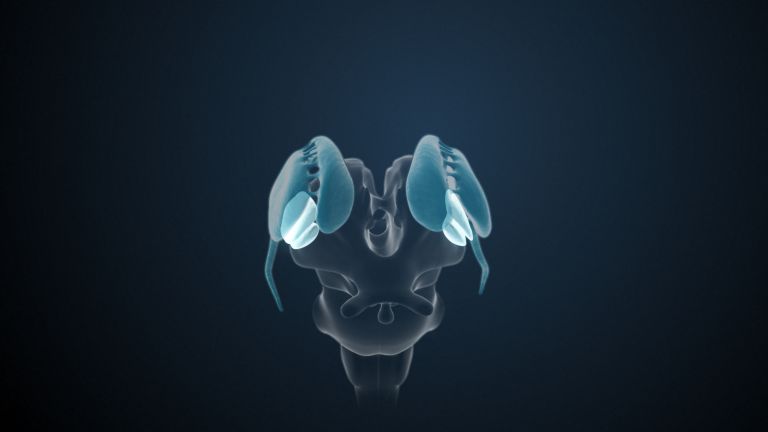

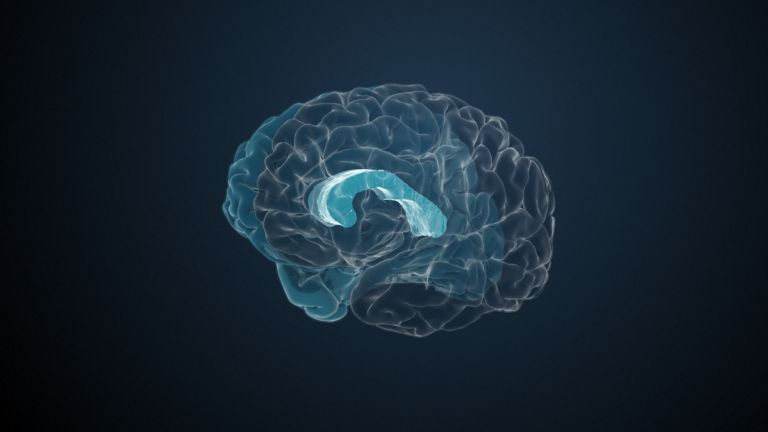

If you cut the Cerebrum horizontally – roughly at Eye level – and lift off the “lid” (so that you can see into the inner cavities of the brain, the ventricles), then visible to the naked eye at the bottom of the right and left lateral ventricles of the temporal lobes is a structure about the length of a little finger, elongated, worm-like, and not at all horse-headed. This is the neuroanatomy of the Hippocampus. Why the Venetian anatomist Julius Caesar Arantius, who coined this term in the 16th century, was reminded of sea horses is completely unclear. Nevertheless the mythological, fish-like name has stuck to this day. After all, even if the horse's head is missing, the hippocampus does have a very long, curved “tail” at the back, known as the Fornix. This bundles not all, but many of the fiber systems through which the hippocampus connects to other regions of the brain.

Cerebrum

telencephalon

The cerebrum comprises the cerebral cortex (gray matter), the nerve fibers (white matter), and the basal ganglia. It is the largest part of the brain. The cortex can be divided into four cortical areas: the temporal lobe, frontal lobe, occipital lobe, and parietal lobe.

Its functions include the coordination of perception, motivation, learning, and thinking.

Eye

bulbus oculi

The eye is the sensory organ responsible for perceiving light stimuli – electromagnetic radiation within a specific frequency range. The light visible to humans lies in the range between 380 and 780 nanometers.

lateral

A positional term – lateral means "towards the side." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction at right angles to the neural axis, i.e., to the right or left.

Hippocampus

The hippocampus is the largest part of the archicortex and an area in the temporal lobe. It is also an important part of the limbic system. Functionally, it is involved in memory processes, but also in spatial orientation and learning. It comprises the subiculum, the dentate gyrus, and the Ammon's horn with its four fields CA1-CA4.

Changes in the structure of the hippocampus due to stress are associated with chronic pain. The hippocampus also plays an important role in the amplification of pain through anxiety.

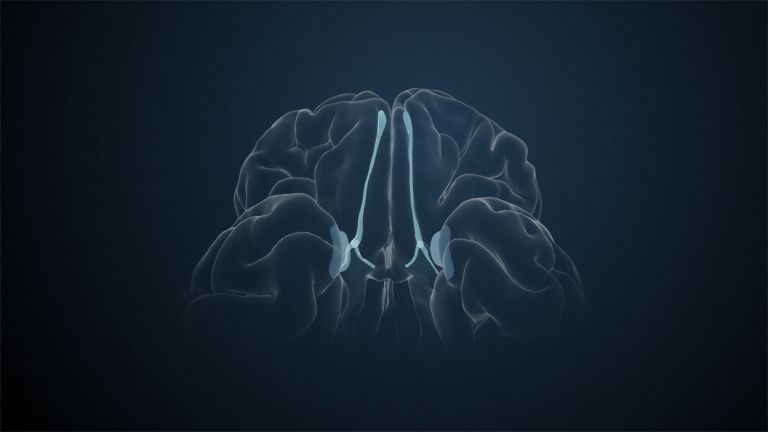

Fornix

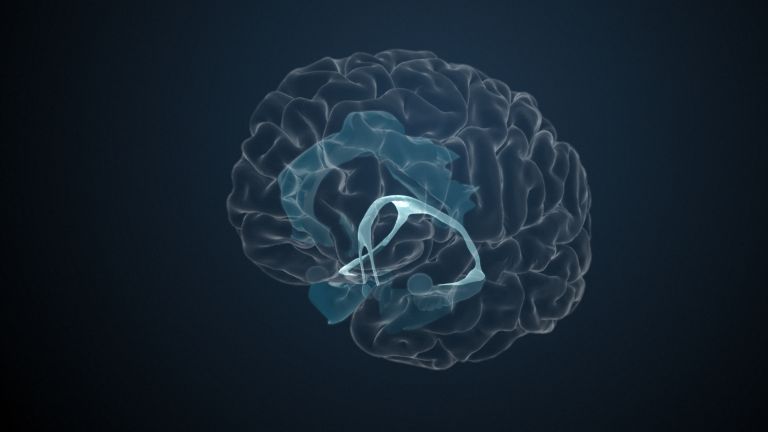

The fornix is a nerve pathway consisting of approximately 12 million fibers that connects the hippocampus (one of the oldest structures in the brain in evolutionary terms) and subiculum with the septum and mammillary bodies.

Internal structure of the hippocampus

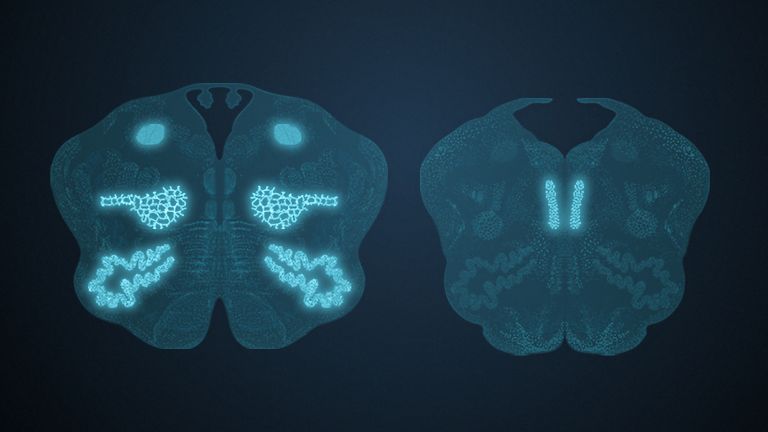

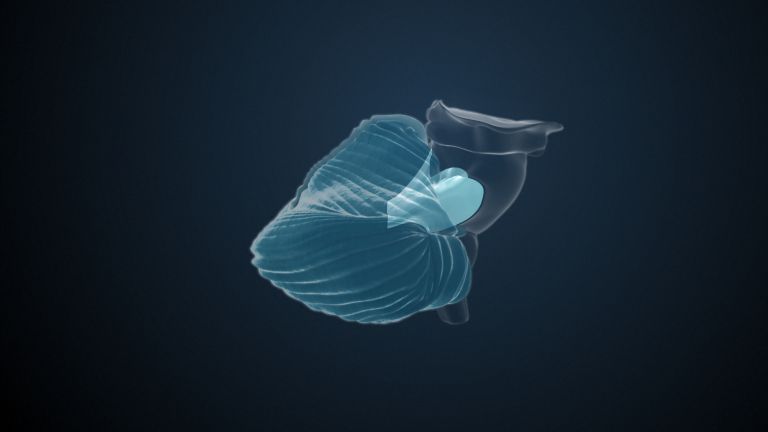

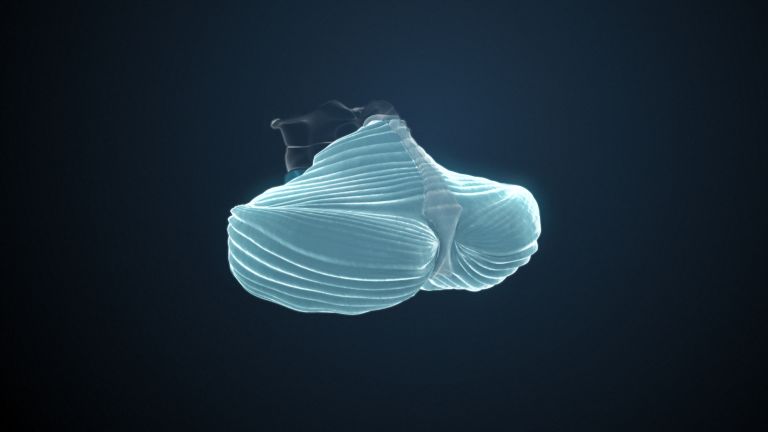

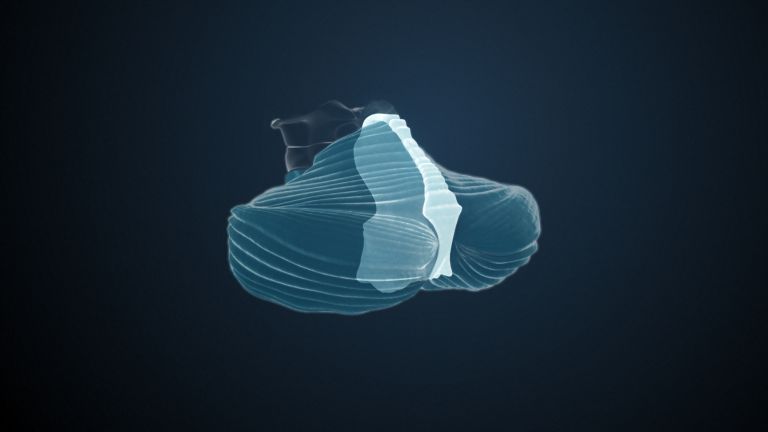

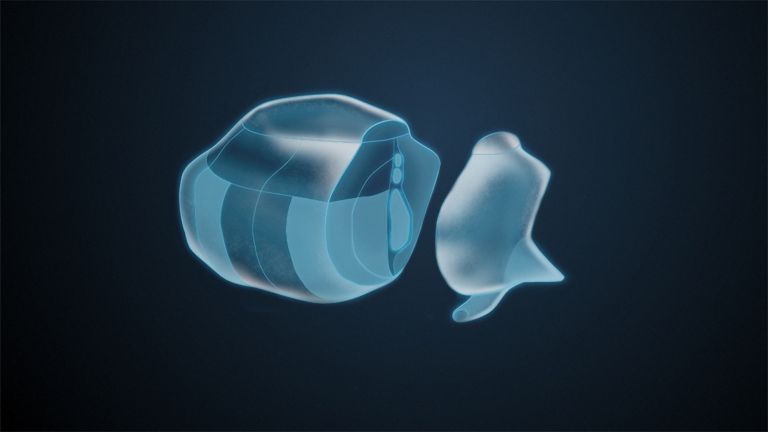

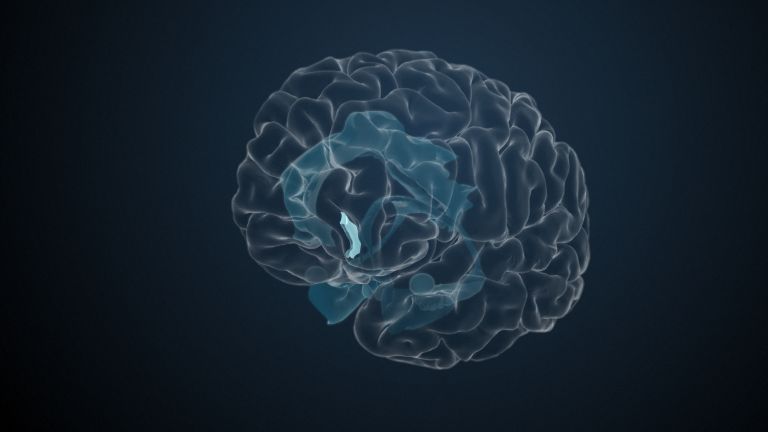

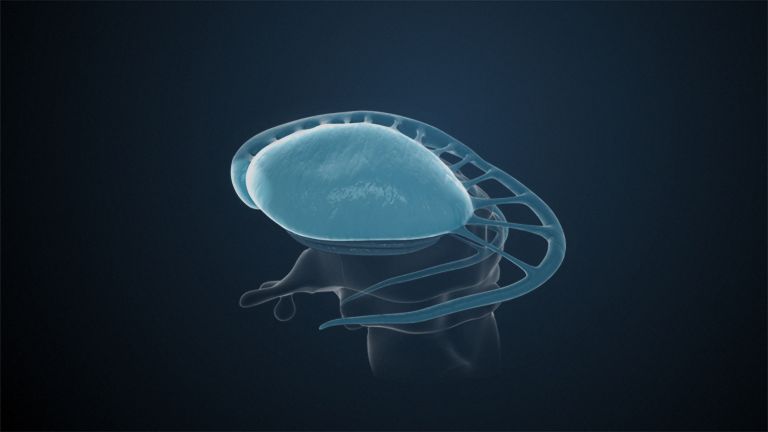

The Hippocampus is a cortical structure and is a large integration area with connections to all areas of the Cortex and the Limbic system It is classified as part of the Archicortex. Like the rest of the cortex, its various subunits – the subiculum, cornus ammonis, and fascia dentata – consist entirely of plate-like layers of neurons. The anatomical terms are once again colourful; the Dentate gyrus is the “toothed band,” the cornus ammonis is the “ram's horn,” and the Subiculum is a “seat cushion”. It's all very figurative – after all, the dentate gyrus looks like a tooth, the ram's horn is curved, and the entire hippocampus sits on top of the subiculum.

The cortex of the hippocampus does not have the typical six layers of the isocortex, which is why it is also referred to as the Allocortex (i.e., “other cortex”). Another typical feature of the hippocampus is the “curling” of these plate-like cortices. When a cross-sectioned is viewed under the microscope, it resembles a pancake lying on its side, with the fascia dentata on the inside and the cornu ammonis wrapped around it.

The main inputs to the hippocampus come from the entorhinal cortex, which is located immediately adjacent to it, right next to the subiculum. They run in the tractus perforans. The entorhinal cortex is itself connected to many association areas of the Neocortex. Inside the hippocampus, between its various divisions (see above), there is a fairly stereotypical “circuit”: the axons of the perforant pathway end at the neurons of the dentate gyrus, whose axons extend to the dendrites of the nerve cells in the cornu ammonis, which in turn send their axons partly to the Fornix and partly to the subiculum. This in turn sends its nerve fibers both to the fornix and back to the entorhinal cortex. The hippocampus therefore has two “main outputs”: (1) via the fornix to the mammillary bodies of the Hypothalamus and to the hippocampal formation in the opposite temporal lobe, and (2) via the subiculum back to the entorhinal cortex. The hippocampus is therefore part of the Papez circuit. Despite this canonical, “rigid” circuit, the hippocampus is (also anatomically) an extremely plastic and dynamic structure (see below).

Hippocampus

The hippocampus is the largest part of the archicortex and an area in the temporal lobe. It is also an important part of the limbic system. Functionally, it is involved in memory processes, but also in spatial orientation and learning. It comprises the subiculum, the dentate gyrus, and the Ammon's horn with its four fields CA1-CA4.

Changes in the structure of the hippocampus due to stress are associated with chronic pain. The hippocampus also plays an important role in the amplification of pain through anxiety.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Limbic system

The limbic system is a functional unit in the brain. It consists of interconnected structures, primarily in the cerebrum and diencephalon. The structures assigned to the system vary depending on the source, but the most important components are the hippocampus, amygdala, cingulate gyrus, septum, and mammillary bodies. The limbic system is involved in autonomic and visceral processes as well as in mechanisms of emotion, memory, and learning. Some authors mistakenly reduce the limbic system to the emotional world by referring to it as the "emotional brain."

Archicortex

An ancient structure of the cerebrum in terms of evolutionary development, which, in contrast to the isocortex (also called the neocortex), has a three-layer structure. The archicortex mainly comprises the hippocampal structures.

Dentate gyrus

gyrus dentatus

The dentate gyrus is part of the hippocampus and acts as its "input station." It receives various sensory inputs from the cortex (cerebral cortex) via the entorhinal cortex. Its densely packed granule cells, which are found in the so-called granular layer, project almost exclusively to the CA3 region of the hippocampus.

Subiculum

The transition zone between the cornu ammonis and the entorhinal cortex is called the subiculum.

Allocortex

A phylogenetically ancient region of the cortex (cerebral cortex) which, unlike the isocortex (also called neocortex), has fewer than six cell layers – in the hippocampus, for example, only three. The allocortex is divided into the paleocortex and archicortex, as well as the periallocortex, which is a transitional form between the allocortex and isocortex.

Neocortex

The neocortex is the phylogenetically youngest part of the cerebral cortex. Since it is structured relatively uniformly in six layers, it is also referred to as the isocortex.

Fornix

The fornix is a nerve pathway consisting of approximately 12 million fibers that connects the hippocampus (one of the oldest structures in the brain in evolutionary terms) and subiculum with the septum and mammillary bodies.

Hypothalamus

The hypothalamus is considered the center of the autonomic nervous system, meaning it controls many motivational states and regulates vegetative aspects such as hunger, thirst, and sexual behavior. As an endocrine gland (which, unlike an exocrine gland, releases its hormones directly into the blood without a duct), it produces numerous hormones, some of which inhibit or stimulate the pituitary gland to release hormones into the blood.In this function, it also plays an important role in the response to pain and is involved in pain modulation.

Recommended articles

Functional failures

The function of a structure can best be assessed when it fails. And so, we now know that the absence of just one Hippocampus is tolerable, however, if both are missing the effect is dramatic. In fact, there have been patients who had to have both hippocampi removed in order to treat otherwise incurable epilepsy. The best-known of these patients is Henry Gustav Molaison (1926–2008), who went down in medical literature as H. M. He became famous for a very typical Memory disorder – an anterograde amnesia, which can occur after an accident involving traumatic brain injury. It affects declarative memory, i.e., the knowledge one has about oneself and the world – from the moment of the triggering event onwards. Motor memory, general finger and movement skills, is not affected.

An anterograde amnesiac can still recall, albeit to a limited extent, the world and autobiographical knowledge they had before the failure of both hippocampi. However, they cannot form new memories, i.e. acquire new knowledge. Time stands still for them; their bodies may age, but their minds remain young. They cannot remember anything for more than a few seconds or minutes. They cannot find anything that they have not stored in the place where they have always kept it. Moving house is perilous as they cannot find their way around a new environment.

These clinical findings are consistent with the fact that the hippocampi of animals that “need to remember well” – squirrels that hide nuts, but also some birds that store food – are extremely large compared to other species that live “from hand to mouth.” Nerve cells have also been found in the hippocampi of rodents that are active only when the animal is in a specific location – these are known as place cells.

A (unfortunately) well-known disease, Alzheimer's dementia, also affects the hippocampus and its surrounding area in its early stages. Neurons of the entorhinal cortex, from which the tractus perforans emerges (see above), are destroyed at an early stage in Alzheimer's disease, with the result that the hippocampus is deprived of its neocortical “inputs” and thus loses the cognitive material that would normally be used to form memories. Memory disorders are the result.

Hippocampus

The hippocampus is the largest part of the archicortex and an area in the temporal lobe. It is also an important part of the limbic system. Functionally, it is involved in memory processes, but also in spatial orientation and learning. It comprises the subiculum, the dentate gyrus, and the Ammon's horn with its four fields CA1-CA4.

Changes in the structure of the hippocampus due to stress are associated with chronic pain. The hippocampus also plays an important role in the amplification of pain through anxiety.

Memory

Memory is a generic term for all types of information storage in the organism. In addition to pure retention, this also includes the absorption of information, its organization, and retrieval.

Learning and the birth of new cells

Finally, the neural mechanism believed to be the physiological substrate of learning has been discovered in the Hippocampus – more precisely, in the interaction of its nerve cells: Long-term potentiation (LTP). In short, nerve cells that fire together, wire together. The underlying LTP is based on a change in the synapses. In the case of synchronization, the transmission from one Neuron to another becomes more effective. To put it bluntly, the “synaptic resistance” decreases.

However, the synapses in the hippocampus are also constantly changing their shape and number. Almost like buds, they can sprout or shrink away from each other, just as if they were drying up, to stick with the image of buds. This so-called synaptic Plasticity plays a decisive role in the activity-dependent modulation of the interconnection of nerve cells.

It has recently been discovered that the hippocampus – its dentate gyrus, to be precise – is one of the few places in the brain where neurons are born throughout life. This is called neurogenesis. We do not yet fully understand what purpose it serves, the newly born nerve cells are integrated into the existing, highly complex intrinsic circuits of the hippocampus. There is evidence that disturbances in this neurogenesis may be linked to depression.

First published on August 23, 2011

Last updated on April 14, 2025

Hippocampus

The hippocampus is the largest part of the archicortex and an area in the temporal lobe. It is also an important part of the limbic system. Functionally, it is involved in memory processes, but also in spatial orientation and learning. It comprises the subiculum, the dentate gyrus, and the Ammon's horn with its four fields CA1-CA4.

Changes in the structure of the hippocampus due to stress are associated with chronic pain. The hippocampus also plays an important role in the amplification of pain through anxiety.

Long-term potentiation

Long-term potentiation is a central mechanism for learning and memory formation. It is based on improved communication between two cells, referred to as strengthening the connection. This strengthening can occur, for example, through an enlargement of the connection point, the installation of new channels, or an increased release of transmitters (messenger substances).

Neuron

A neuron is a specialized cell in the nervous system that is responsible for processing and transmitting information. It receives signals via its dendrites and transmits them via its axon. Transmission occurs electrically within the neuron and, between neurons, usually chemically via synapses.

Plasticity

Neuroplasticity

The term neuroplasticity describes the ability of synapses, nerve cells, and entire areas of the brain to change structurally and functionally depending on the degree to which they are used. Synaptic plasticity refers to the adaptation of the signal transmission strength of synapses to the frequency and intensity of incoming stimuli, for example in the form of long-term potentiation or depression. In addition, the size, interconnection, and activity patterns of different areas of the brain also change depending on their use. This phenomenon is referred to as cortical plasticity when it specifically affects the cortex.

Depression

A mental illness whose main symptoms are sadness and a loss of joy, motivation, and interest. Current classification systems distinguish between different types of depression.