René Descartes: Father of the Body-Mind Theory

The French philosopher René Descartes believed that the brain controls the body as the highest authority. He advocated the theory of body and soul as separate entities and thus shaped the way we think about mind and body to this day.

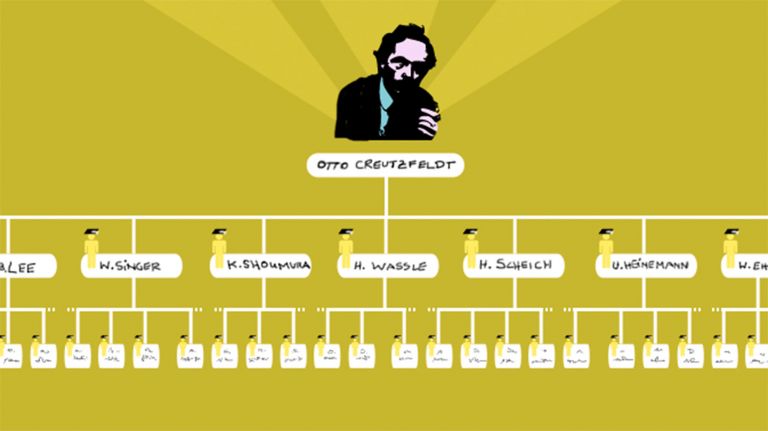

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang U. Eckart

Published: 02.05.2016

Difficulty: intermediate

- René Descartes recognized that the human body is controlled by the brain.

- The body for him was a mechanically functioning machine.

- He divided humans into body and soul (dualism) and believed that both interact with each other via the pineal gland in the brain.

- Descartes believed that movements occur when the gaseous life spirit was pumped through the nerves to the muscles, causing them to contract.

- However, feelings, voluntary actions, and conscious perceptions were only possible because of the soul organ, the pineal gland, in the brain.

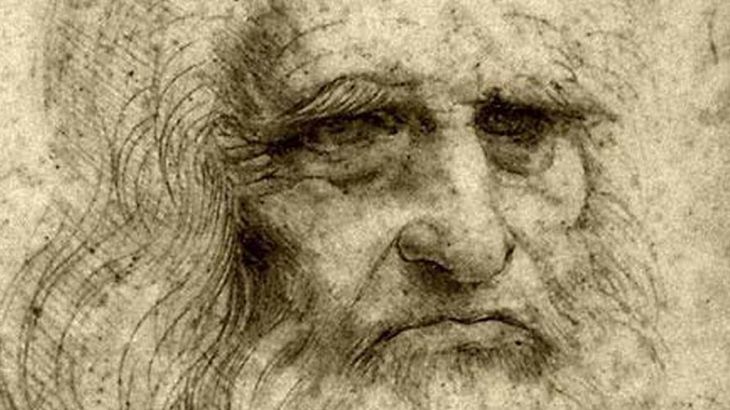

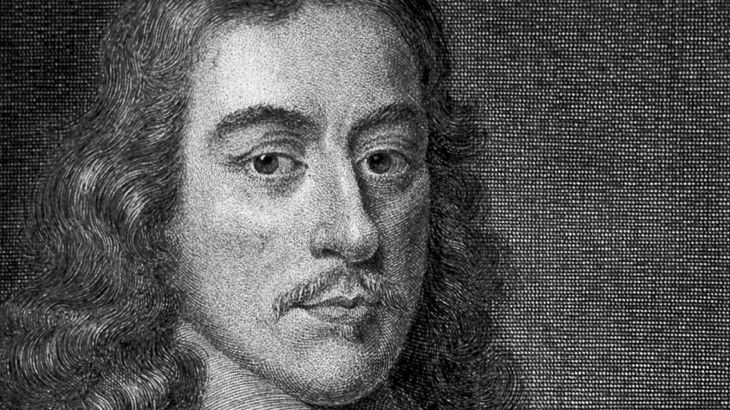

One thing can be said with certainty: French philosopher René Descartes did not want to cause offense with his theory of man. And yet his ideas were so ahead of their time that they shaped philosophy, mathematics, and the natural sciences long after his death.

Descartes is considered the founder of rationalism, and also the spiritual father of the division of body and soul into separate entities that nevertheless interact with each other. This dualism persists to this day in the language and thinking of many people, for example when doctors distinguish between mental and physical complaints and describe the mutual influence as “psychosomatic.” But even common idioms embody this dualistic understanding: for example, we talk about something being on our mind or weighing on our soul, without there being any physical counterpart.

The son of a court councilor, born in France in 1596 and died in Stockholm in 1650, lived at the beginning of the modern era – and thus in a time when people were strongly religious and the natural sciences were still not very differentiated. Many a learned contemporary had to pay dearly for this constellation. One example is Galileo Galilei, who was sentenced to death in an Inquisition trial because of his writings (however, he escaped the stake by officially renouncing his beliefs). With the help of an improved telescope, the astronomer had provided evidence that the Earth revolves around the Sun and not vice versa, as the Catholic Church claimed at the time.

The verdict must have come as a shock to Descartes: Galileo's writings, which also established the laws of motion in physics, and thus his mechanistic worldview, were known to Descartes, as documented in letters, and, according to British philosopher Gilbert Ryle, prompted him to suspect similar mechanisms in humans. Descartes never published one of his central works, Treatise on Man, during his lifetime for fear of displeasing the clergy. At least, that is how Jack Rochford Vrooman interprets it in his Descartes biography. The treatise was only printed posthumously.

Fountain or organ?

Even before Descartes, the body was considered the seat of the immortal soul. But little importance was attached to it, and certainly no one imagined that the two interacted with each other. The body was considered a mere shell and was therefore rarely examined or autopsied in detail for a long time. From the 12th century onwards, the Church prevented bloody operations and autopsies at universities. Nevertheless, individual scientists repeatedly disregarded this directive. Eventually, the anatomist ▸ Andreas Vesalius even performed public autopsies. However, in line with the ideas of the Christian church and based on Galen's work, many scholars imagined the brain as a kind of Roman fountain, a canal system fed by a cistern containing the airy spirit of life, according to neurobiologist Robert-Benjamin Illing from the University Medical Center Freiburg. This was one of the first significant metaphors for how the brain works, but not the only one. “Descartes first described this idea of the Roman fountain in great detail, only to then pick it apart,” Illing said in a radio interview.

He soon began to doubt this idea. How could a sluggish fountain explain lightning-fast perception: hearing, seeing, and touching in fractions of a second? And what about the speed of human movements? Descartes saw the human body more as a machine coordinated by the brain. This physical world, which he called “res extensa,” consisted of tiny particles and had a defined extent. It could not produce thought, only action and reaction.

The brain, as well, he saw as a mechanical device and described it like an organ: just as air was guided through the musical instrument, the airy spirit of life travelled from the brain to the body via the nerves – similar to a gentle wind, driven by the heart and arteries. Only in this way were diverse and differentiated perceptions and physical reactions possible, just like the different tones of the instrument. Unlike the fountain with its storage vessels, which fill slowly, the organ could react much faster.

Descartes imagined the nerves as hollow and equipped with valves. In the arms and legs of the body, they then merged with the muscles. The gaseous spirit of life thus caused the muscles to harden and, in a sense, pumped up the limbs. Because, according to his theory, every movement is due to a movement of gas, namely the spirit of life, Descartes and his followers were also called “balloonists” by their contemporaries with a certain degree of irony.

Recommended articles

A soul organ in the head

In this mechanical view of humanity, Descartes also had room for the soul as a kind of counterpart. The world of thought, “res cogitans,” had no defined boundaries in space and was immaterial. But it was responsible for feelings, conscious perceptions, reflection, and voluntary actions. And, of course, as a God-fearing man, he considered it immortal. However, he believed that only humans possessed a soul. The philosopher regarded animals as mere machines.

Unlike his predecessors, Descartes believed in an interaction between body and soul, and suspected that this interaction took place in the brain, in the so-called pineal gland. This had already been described by scholars before him, such as the Greek anatomist Galen, who correctly located the cone-shaped pineal gland in the diencephalon. However, he considered it to be a valve that coordinated the flow of thoughts in the lateral ventricles. Based on this preliminary work, Descartes also assumed that the pineal gland was located under the brain, roughly in the middle of the head, without ever having seen it. This was because he only occasionally dissected animal heads, which, in his understanding, did not need a pineal gland as they were soulless beings. In fact, we now know that he was wrong: animals also have this organ. “With the idea of the pineal gland, Descartes created a paradigm, namely that the organ of the soul is part of the brain,” says science historian Michael Hagner from ETH Zurich.

Was von Descartes geblieben ist

Today, the division of body and soul is considered outdated in brain research, nor has it ever been possible to discover an interaction center in the brain. The balloon theory has long since been replaced by the understanding of nerve impulse conduction via electrical potentials.

During Descartes' lifetime, his contemporary Giovanni Borelli conducted an experiment that would be considered unethical today, but which challenged the idea of an airy life spirit. He held an animal underwater, which struggled violently to prevent itself from drowning. To test whether the muscles were activated by an airy substance, Borelli dissected the animal underwater. No gas bubbles rose to the surface. Borelli concluded, seemingly obvious but equally wrong, that the spirit of life was more fluid. Another aspect of Descartes' understanding of the mind is also considered outdated today: he considered all thinking to be a conscious process. However, neurologists now know that the vast majority of thought processes remain hidden from us.

And yet, the brain is still largely regarded as the supreme ruler of the body, just as Descartes believed – even though autonomous reactions of the peripheral nervous system, such as those observed when playing music or dancing, are receiving increasing attention. For over 150 years, the concept of the dualism of body and soul and an interface in the brain prevailed. It also enabled scientific study of the body, but did not deny the divine origin of the soul.

This was important to Descartes. It would therefore have been particularly devastating for the French philosopher to learn that the Church had turned against him after his death: in 1663, one year after the posthumous publication of his work Discourse on Man, the Vatican placed Descartes' writings on the Index of Prohibited Books. Church representatives found his ideas too revolutionary. He encouraged constant doubt: “I think, therefore I am,” was how he defined human beings. This constant questioning can be understood as contrary to the idea of faith. However, according to philosopher Hans-Peter Schütt from the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, representatives of the Catholic Church also took issue with the fact that, according to Descartes' philosophy, the bread and body of Christ belonged to the physical world, which contradicted the biblical transformation of bread into the body of Christ.