Konrad Lorenz: Behavioral scientist and father of geese

Konrad Lorenz is considered one of the co-founders of behavioral research. He received the Nobel Prize for his research. He supported Nazi ideology.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Ute Deichmann

Published: 21.08.2014

Difficulty: intermediate

- Austrian Konrad Lorenz is considered the “father of geese” and co-founder of comparative behavioral research, known as ethology.

- In 1973, Konrad Lorenz, together with Karl von Frisch and Nikolaas Tinbergen, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine “for their discoveries concerning the structure and triggering of individual and social behavior patterns.”

- Konrad Lorenz wrote various papers using Nazi terminology and had applied to join the NSDAP. Whether he truly adhered to Nazi ideology or was a naive or calculating follower remains unclear.

- Konrad Lorenz's theories on innate instinctive behavior and imprinting are now considered outdated. Today, animal behavior is explained more with the help of sociobiology, behavioral economics, and neurobiology.

In 1935, the gray goose Martina hatched from her egg and was imprinted on Konrad Lorenz. A year later, she and the gander Martin became a goose couple. Another year later, the two geese flew away and were never seen again. However, Konrad Lorenz reported on Martina repeatedly throughout his life, even though he observed hundreds of gray geese during his years of research. The anecdotes changed over time, as science historian Tania Munz has analyzed: In Konrad Lorenz's writings, Martina had “led a lavish and changeable life.” In the 1930s, Konrad Lorenz initially wrote only of “a goose” in order to portray stereotypical behavior for the entire goose species. During the Nazi era, Martina and the gander Martin were presented as an example of a successful couple and as a contrast to domesticated geese, which were supposedly dangerous and had a stronger sex drive. Later, Konrad Lorenz focused on Martina as an individual in his writings and presented himself as her chronicler. And even later, Lorenz portrayed Martina as abnormal in his texts, along with some stress-related behavioral abnormalities.

November 7, 1903 Konrad Zacharias Lorenz is born in Vienna.

1922–1928 Studies medicine at Columbia University in New York and at the University of Vienna, including receiving his doctorate.

1927 Marries Margarethe Gebhardt, his childhood friend. The couple has three children.

1928–1936 Studies zoology at the University of Vienna, earns a second doctorate, then a postdoctoral qualification. At the same time, works as an assistant at the Anatomical Institute.

1940–1941 Professorship in psychology at the University of Königsberg.

1941–1948 Wehrmacht soldier and prisoner of war in the Soviet Union.

1949 Publication of his most popular book to date, He Talked to the Cattle, the Birds, and the Fish.

1950–1955 Research cent er for comparative behavioral research at the Max Planck Society in Buldern, Westphalia.

1955–1973 Founding director at the Max Planck Institute for Behavioral Physiology in Eßsee, Bavaria.

1973 Nobel Prize in Medicine together with Karl von Frisch and Nikolaas Tinbergen.

1985 He is the namesake of the Konrad Lorenz referendum against a hydroelectric power plant. Previously, he was the figurehead of a successful referendum against the Zwentendorf nuclear power plant in Austria.

February 27, 1989 Konrad Lorenz dies in Vienna after acute kidney failure.

Fourteen-year-old Nils is lazy and constantly plays pranks. As punishment, he is turned into a gnome and travels across Sweden on the back of a gander, all the way up to Lapland. The Wonderful Adventures of Nils Holgersson with the Wild Geese is the name of this story, written by Selma Lagerlöf at the beginning of the 20th century. It was actually intended for regional studies lessons in Swedish schools. But in Austria, in Altenberg near Vienna, a little boy was also read this story.

The boy was only five years old, but the story stayed with him: “Since then, I have longed to become a wild goose; and when I realized that this was impossible, I desperately wanted to have one; and when it turned out that this was also impossible, I contented myself with having domesticated ducks.” This is how he remembers it almost seven decades later, when he receives the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine at the end of 1973, now an old man with a stately white beard: Konrad Zacharias Lorenz.

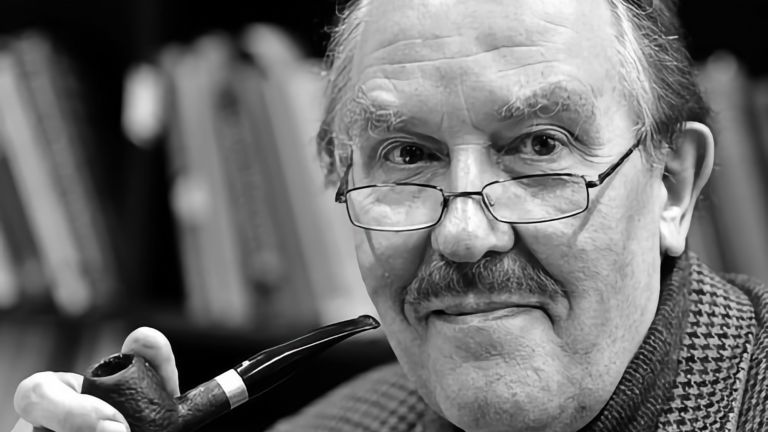

The scientist Lorenz became famous as the “father of geese.” And he went down in scientific history as much more than the co-founder of comparative behavioral research, known as ethology. But Lorenz the man was complex, and today his temporary proximity to Nazi ideology leaves a rather uneasy feeling.

Early fascination with geese

Perhaps everything would have turned out differently if Konrad Lorenz had not been a latecomer, born in 1903, 18 years after his brother Albert. Had he been older, the book about Nils and the geese, published in 1906, would probably not have fascinated him so much. Perhaps his life would also have taken a different course if his mother Emma had not bought two ducklings from a neighbor; one for little Konrad, his mallard, and one for Konrad's playmate Margarethe Gebhardt. The two played “duck parents” all summer long. And even then, Konrad noticed that his own duck followed him everywhere, while the other duck waddled after neither him nor Margarethe. Over time, the budding researcher turned the Lorenz family estate into a small zoo, with jackdaws in the attic and ducks in the garden pond.

Years later, Lorenz studied medicine at Columbia University in New York and at the University of Vienna – albeit rather reluctantly and only to please his father. He earned his doctorate, studied zoology, earned a second doctorate, and finally qualified as a professor. He married his girlfriend Margarethe; they had two daughters and a son. And he raised Martina, probably the most famous gray goose in the world.

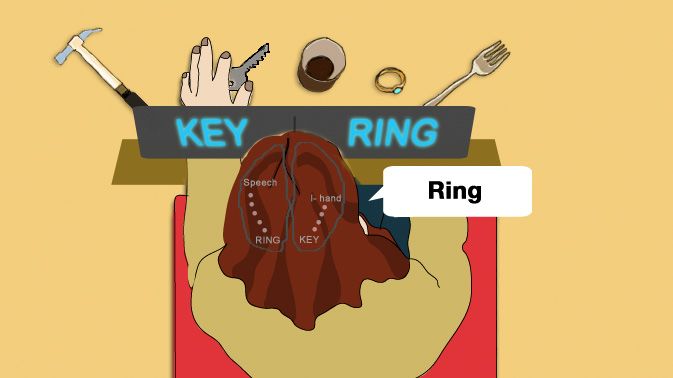

The principle of imprinting

The first thing Martina saw as a newly hatched chick was Konrad Lorenz: she is said to have raised her head and chirped at Lorenz. After a while, he wanted to push the chick under the mother goose's belly, but it only followed him – just like his first mallard duck once did. Every evening, Martina climbed the stairs to the bedroom with Lorenz and flew out the window the next morning. The researcher was convinced that Martina had been imprinted by him and was therefore fixated on him. He believed that chicks' tendency to follow someone was innate and therefore described this behavior as an instinctive movement. Normally, they follow their mother. But newly hatched chicks first have to learn who that is.

The mother is a large, mobile something that makes noises and is very close to you – because the mother would not let anyone else near her nest. But in this case, there was Konrad Lorenz, and the animal learned to consider him its mother. Thus, it was the human and not the goose that became the key stimulus – the stimulus that triggered the following behavior. Konrad Lorenz called the connection between instinctive behavior and learned stimulus the “innate triggering mechanism.” All of this together resulted in his concept of imprinting and his theory of instinct, which he presented in 1937 in his treatise On the Concept of Instinctive Action.

Comparative behavioral research

Konrad Lorenz himself called his field of research “animal psychology,” thus becoming one of the founding fathers of ethology – comparative behavioral research. It stood in contrast to classical behaviorism, which dominated psychology at the time and sought to explain all behavior through unconditioned and learned reflexes.

However, this contradicted Lorenz's observations of instinctive behavior – for example, when birds know how to peck at food grains without anyone having shown them how. Or when robins recognize a male intruder in their territory solely by its red color – and a simple tuft of red feathers is enough to trigger defensive behavior.

The road to Nazi Germany

Ethology was based on Darwin's fundamental assumptions: behavior, like anatomy, must have developed according to random variability and corresponding selection advantages. This proved to be a problem, because Darwin was not well liked in Austria in the 1930s – the country was strongly Catholic. Lorenz was banned from conducting his ethological research, so he left the University of Vienna and continued to work unpaid at home in Altenberg. In 1937, he applied for funding in Nazi Germany from the Emergency Association of German Science, a precursor to today's German Research Foundation. The application was rejected because “above all, the political views and ancestry of Dr. Konrad Lorenz were called into question.”

A few months later, Konrad Lorenz reapplied for project funding. Letters of recommendation from colleagues now attested that he was of Aryan descent, that “Dr. Lorenz's political views are impeccable in every respect,” that he had “never made a secret of his approval of National Socialism,” and that his biological research was in line with the views of the German Reich. Lorenz received the money and went on to research how the instinctive behavior of wild geese changes when they are bred as domestic animals or crossed with domestic geese.

In March 1938, the Germans marched into Austria. In June 1938, Konrad Lorenz applied for membership in the NSDAP. Two years later, he became professor of psychology in Königsberg, a position once held by Immanuel Kant. In 1941, he was drafted into the Wehrmacht, where he worked as a psychiatrist and neurologist in a military hospital in Poznan, Poland. He was later sent to the front and soon fell into Russian captivity. In 1948, Lorenz returned to his homeland, to Altenberg near Vienna.

“Racial hygiene defense”

In an interview on the occasion of his 85th birthday, Lorenz explained: "And I also shied away from all politics because I was preoccupied with my own problems. I also avoided any confrontation with the Nazis in a very contemptuous manner; I simply didn't have time for it." That was in 1988, shortly before his death, when Lorenz was a celebrated member of the Austrian environmental movement, warning against nuclear power plants, technologization, and ecological disasters.

His statements do not fit in at all with his activities as an army psychologist, who not only worked in the reserve hospital in Posen, but also conducted studies on “German-Polish mixed-race people.” He came to the conclusion that Polish genetic material was characterized, for example, by “fear of life, impulsive dynamics, and a lack of vital roots.” As a result, he feared that “physical and moral signs of decay, which cause the decline of civilized peoples after they have reached the stage of civilization, are essentially the same as the signs of domestication in domestic animals” and therefore called for a “conscious, scientifically-based racial policy.” The goal was the “improvement and enhancement of the people and race.” He speaks of “full-fledged” and ‘inferior’ individuals and advocates measures to “eradicate the inferior.”

Regarding his own research, he stated: “We confidently predict that these studies will be fruitful for both theoretical and practical racial policy concerns.”

All these statements come from Konrad Lorenz of the Third Reich. In 1981, however, he stated in a television interview: “I really didn't believe at the time that people meant murder when they said ‘extermination’ or ‘selection’. I was so naive, so stupid, so gullible – call it what you will – back then.”

Recommended articles

Nobel Prize

It is a dark, brown chapter in Konrad Lorenz's biography. Did he really adhere to Nazi ideology, or did he get lost in the homology between geese and humans and become a naive follower rather by accident? The Nobel Prize Committee is also said to have discussed this. In the end, Konrad Lorenz did indeed receive the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1973, together with his colleague Nikolaas Tinbergen and zoologist Karl von Frisch, who had primarily studied the sensory perception of honeybees. The researchers received the prize “for their discoveries concerning the organization and triggering of individual and social behavior patterns.”

Outdated theories

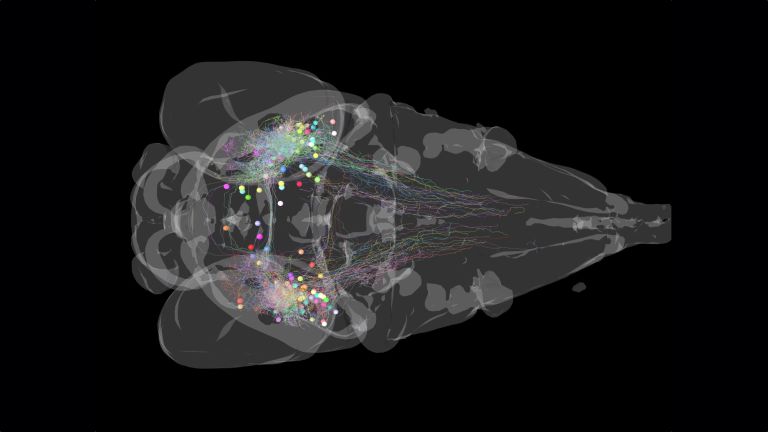

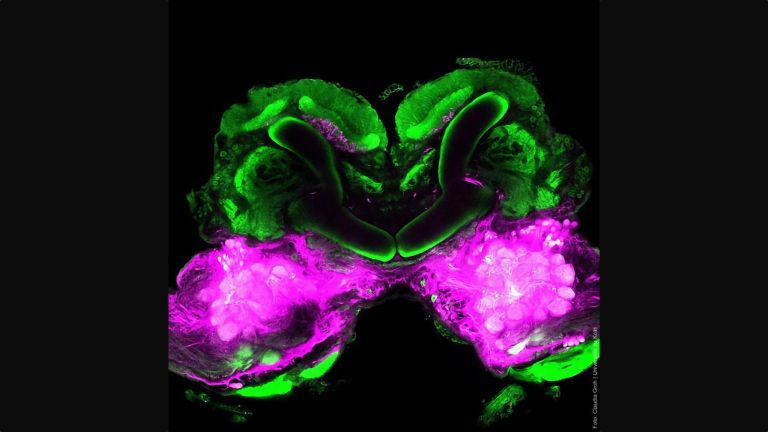

Lorenz disliked experiments: he wanted to study animal behavior through observation alone. And even though terms such as imprinting, instinct, and innate trigger mechanisms can still be found in many school textbooks, Lorenz's theories are now considered outdated. Nowadays, attempts are made to explain how the behavior of animals – and humans – is influenced from a socio-biological, behavioral-ecological, or neurobiological perspective.

On February 27, 1989, Konrad Lorenz died at the age of 85 after suffering acute kidney failure. Shortly before, he had dictated to his secretary: “The reputation of my contemporaries, especially the scientific ones, claims that I am a great man, and they must know better than I do. When I look back and try to highlight what I am proud of, the result is modest – honestly!” Such understatement was unusual for Lorenz. After all, he did win a Nobel Prize.

Further reading

- Munz, T: “My goose child Martina“: the multiple uses of geese in the writings of Konrad Lorenz. In: Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences, Vol. 41 (4), S. 405 – 446, 2011. Abstract