Andreas Vesalius: Founder of modern Anatomy

Anatomy is learned by looking: Andreas Vesalius replaces belief in authority with empiricism, makes the dissection of corpses socially acceptable, and leaves behind a masterpiece of book art.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang U. Eckart

Published: 01.05.2016

Difficulty: intermediate

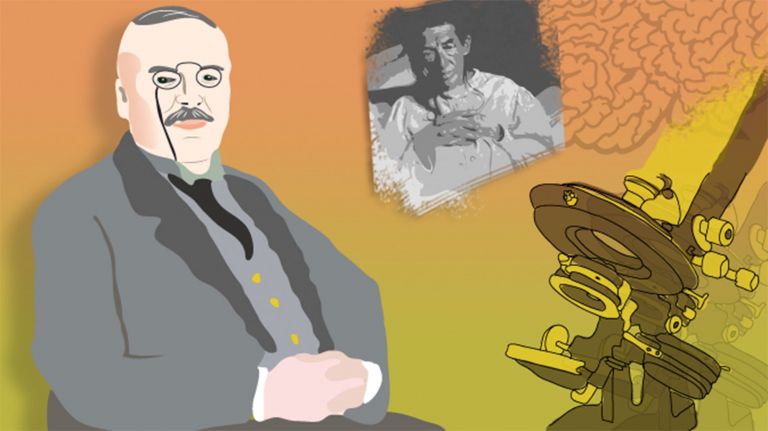

- Until the Renaissance, Claudius Galenus was the authoritative figure in anatomy. However, he had mainly conducted research on animals and extrapolated his findings to humans.

- Andreas Vesalius studied Galenic anatomy but recognized how much Galen's descriptions deviated from his own observations and addressed this more clearly than his predecessors.

- With his anatomical atlas, he created a fundamental work of modern anatomy and a masterpiece of book art.

- Vesalius corrected numerous errors made by Galen, including assumptions about the anatomy of the brain.

You learn less at this spectacle than at the butcher's market: Andreas Vesalius, who had come to Paris in 1533 to study medicine and anatomy with famous scholars such as Jacobus Sylvius, was disappointed. Anatomy lessons in the 16th century meant that the professor would recite the writings of the Roman physician Claudius Galenus from a raised platform and instruct a “barber” to expose the corresponding organ on a corpse.

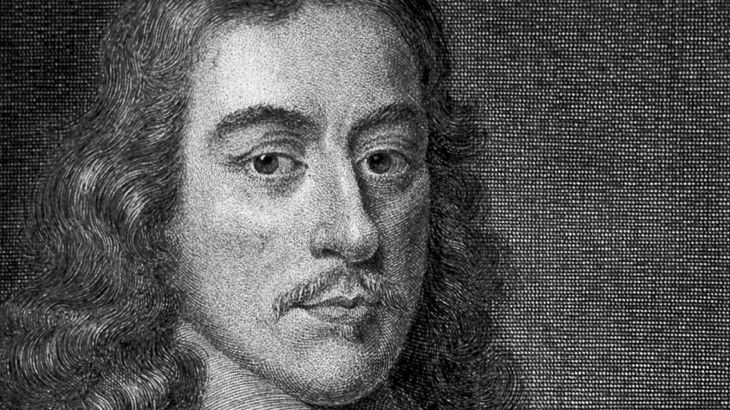

Galen, who had written numerous medical treatises in the 2nd century, was still the authoritative figure in conservative Paris. However, because Roman law of his time prohibited the dissection of human bodies, Galen resorted to studying animal carcasses – and drew conclusions about human anatomy from their anatomy. If dissection revealed deviations from his descriptions, Vesalius lamented, the lecturers ignored them, resorting to the adventurous theory that human anatomy had changed since Galen's time. Or they lost themselves in scholarly debates.

Early doubts

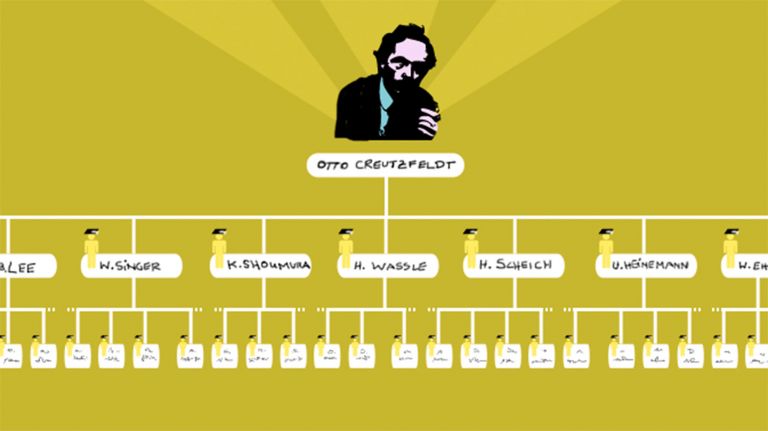

Vesalius (1514–1564) was not the first to dare to criticize Galen, but he contributed significantly to ending this malpractice in anatomy. Today, he is considered the founder of modern anatomy.

His family name, Vesalius, recalls their origins in Wesel in northern Germany. Vesalius' father was a pharmacist at the imperial court of Charles V in Brussels and is said to have introduced his son to medicine and medical books at an early age. According to his biographers, even as a child he would wander around the place of execution near his parents' house and look at the remains of hanged criminals. At the age of fifteen, Vesalius enrolled at the University of Leuven, which was then considered the spearhead of humanistic ideals: independent thinking was to replace parroting the authorities. Vesalius studied the classical subjects of grammar, rhetoric, algebra, and astrology, as well as music, Greek, and Hebrew. At the age of 18, he went to Paris to study anatomy and medicine. There, Vesalius thoroughly studied Galen and even contributed to an edition of his writings. In addition, his teachers assigned the ambitious and talented student the task of dissecting corpses in their anatomy lectures. However, it became increasingly clear to Vesalius that the traditional teachings did not match his observations.

In 1536, war broke out between the French king and Emperor Charles V. Vesalius fled back to Leuven. His social contacts enabled him to obtain permission to perform public dissections, which attracted great interest. Unlike his teachers, he did not employ assistants for the dissections, but did the work himself. And he did not cut open the corpses in the usual way to reach a specific organ, but exposed them layer by layer.

In 1537, Vesalius went to Padua, a stronghold of modern anatomy at the time, where he received his doctorate in medicine and was appointed professor of surgery on the same day. Here, too, public dissections were part of his duties. To this end, he was provided with the corpses of executed criminals. A copperplate engraving shows Vesalius surrounded by a dense crowd of students and older spectators, his hand on the corpse. Those who wanted to stand close to the table had to pay a higher admission fee.

A major work of almost 700 pages

Vesalius' next stop was Venice, where he also taught anatomy and, in 1538, published six anatomical plates as teaching material for students, which were produced by the painter and graphic artist Jan Stephan van Calcar, a Pupil of Titian. These plates are still very much in the tradition of Galen. Then, in 1543, when Vesalius was only 28 years old, his magnum opus was published in Basel: an anatomical atlas entitled“De humani corporis fabrica libri septem: Seven Books on the Structure of the Human Body. It was a monumental work, large-format, with almost seven hundred pages and more than two hundred illustrations. In it, Vesalius summarizes his findings on the human body, takes up the cudgels for empirical research, pays tribute to Galen, but points out numerous errors in his work. Believing his work to be too extensive for a large readership, Vesalius published an abridged version a few months later, called Epitome, or Excerpt. It quickly became the standard work for students and physicians.

The artistic woodcuts illustrating the work contributed significantly to its success. The templates for these were probably created in part by Vesalius himself and in part by Jan Stephan van Calcar and other artists from Titian's workshop. His detailed, elegant, and often allegorical presentation of the human body seems like a template for Gunther von Hagens' body museum. Some of the terms he coined have survived to this day, such as the names Hammer and Anvil for two of the ossicles.

The first book of the Fabrica deals with the human skeleton, the second with the muscles, the third with the veins, and the fourth with the nerves, about which Vesalius states that even the thickest of them are not hollow and therefore cannot transport fluid, as Galen had claimed: “I have carefully examined the nerves and treated them with warm water, but I could not find any passage of this kind in the entire course of the nerve,” he wrote. Books five and six deal with the abdomen and chest cavity, and the seventh with the brain “as the dwelling place of living potential and the instrument or tool of reason.” In this book, Vesalius provides a detailed description of the cerebral ventricles, the meninges, and the veins that supply the brain. He distinguishes between the white and Gray matter of the cerebral cortex, describes structures such as the corpus callosum, cerebellum, pons, and amygdala, and also devotes Attention to the sensory organs. He stated that the principle of symmetry that governs the human body cannot be extended to the brain. The woodcuts of brain preparations made according to his drawings were considered benchmarks for the next two hundred years.

Pupil

The opening in the eye through which light enters. The size of the pupil is determined by the iris and changes reflexively (pupillary reflex). This process of adjusting to the brightness of the environment is called adaptation.

Hammer

maleus

The first of the small ossicles in the middle ear. It is connected to the eardrum and transmits the vibrations caused by sound waves via the other two ossicles (incus, stapes) to the cochlea, where the stimulus is converted into a neural signal.

Anvil

incus

The middle of the three ossicles in the middle ear transmits the vibration from the malleus to the stapes.

Ossicles

The three bones located in the middle ear – the stapes, malleus, and incus – are known as the ossicles. These are the smallest bones in the human body. They mechanically transmit sound waves from the eardrum to the cochlea.

Gray matter

Grey matter refers to a collection of nerve cell bodies, such as those found in nuclei or in the cortex.

Attention

Attention

Attention serves as a tool for consciously perceiving internal and external stimuli. We achieve this by focusing our mental resources on a limited number of stimuli or pieces of information. While some stimuli automatically attract our attention, we can select others in a controlled manner. The brain also unconsciously processes stimuli that are not currently the focus of our attention.

Recommended articles

Confronting Galen's theories

And he did not shy away from conflict: according to Vesalius, the “rete mirabile” described by Galen, a network of arteries at the base of the skull in which the spirit of life arises, could not be found in the brain. Other researchers before him had already made this observation, but no one had dared to state it so clearly. Vesalius also attacked the ventricle theory, according to which human cognitive abilities are located in the fluid-filled cavities of the brain. In fact, Vesalius stated that the human brain does not differ from that of animals in terms of ventricles and concluded that they cannot be the seat of the mind or soul. On some other points, however, Vesalius remained traditional, assuming, for example, that a life spirit made the heart beat. The brain serves to mix this life spirit with the air we breathe, thus creating an “animal spirit” that is then transformed into the “highest spirit,” explain Marco Catani and Stefano Sandrone in their book, published on the 500th anniversary of Vesalius' birth and 450th anniversary of his death. And he reflected on the limits of his possibilities: Neither the dissection of living animals nor human corpses was sufficient to discover how the brain realizes thought, imagination, and memory.

After the publication of his magnum opus, Vesalius ended his scientific career and became personal physician to Emperor Charles V and later to his son, Philip II. From 1559, he lived in Madrid, where the imperial court had been relocated. He published only minor writings on various new treatment methods and gained a reputation as a successful surgeon. He also repeatedly defended himself against attacks by his critics, especially his former teacher Sylvius, who described him as a ridiculous madman and ungrateful monster who would infect the whole of Europe with his “pestilence.”

In 1549, he set out on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem but died on the return journey on the Greek island of Zakynthos, where his ship was stranded after a storm. His work has been preserved not only in his writings, but also in the form of the world's oldest anatomical specimen: the skeleton of Jakob Karrer von Gebweiler, who was beheaded in 1543 for attempting to murder his wife. It is on display, albeit without hands, in the Anatomical Museum in Basel.

Memory

Memory is a generic term for all types of information storage in the organism. In addition to pure retention, this also includes the absorption of information, its organization, and retrieval.

Revolutionary and conservative

Vesalius' significance for medicine is often compared to that of Copernicus for astronomy, whose work on the movements of the heavens was published in the same year as the Fabrica. Critical voices point out, however, that in many respects he tended to follow Galen rather than relying on empirical evidence. “It was both revolutionary and very conservative. It was so close to modern medicine, there were so many things he could have noticed,” said emeritus historian Daniel H. Garrison of Northwestern University in an interview about the new edition of the Fabrica. Thus, he supplemented ancient anatomy rather than revolutionizing it. In addition, he owed his status to a skillful self-promotion that simply ignored his predecessors and colleagues. Vesalius liked to stylize himself as a scientist and adventurer who fought with his life and limb for his research, with dramatic stories of corpses stolen from the cemetery in the dark of night or cut down from the gallows and smuggled into the city.

Whether Vesalius really wanted to knock Galen off his pedestal or rather supplement his anatomy is a matter of debate. What is clear is that the Fabrica contributed to undermining Galen's authority: Vesalius uncovered numerous errors in it, thereby strengthening empirical research. And Vesalius's anatomical atlas itself served as a guide to the human body far beyond the Renaissance. Even today, we learn more from his writings than we do from the butcher at the market.

Further reading

- Vesalius, A.: The Fabric of the Human Body. An Annotated Translation of the 1543 and 1555 Editions of “De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem”, by D.H. Garrison and M.H. Hast, Basel, 2014.

- Marco Catani, Stefano Sandrone: Brain Renaissance. From Vesalius to Modern Neuroscience. Oxford University Press 2015 (Mit englischer Übersetzung der Kapitel über das Gehirn).