Roger Sperry: The split Brains

Cutting the corpus callosum between the two hemispheres of the brain sounds like something out of a bad horror movie. But this type of split-brain surgery helps patients with severe epilepsy: Roger Sperry researched the consequences and was awarded the Nobel Prize for his work.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Axel Mecklinger

Published: 27.09.2012

Difficulty: intermediate

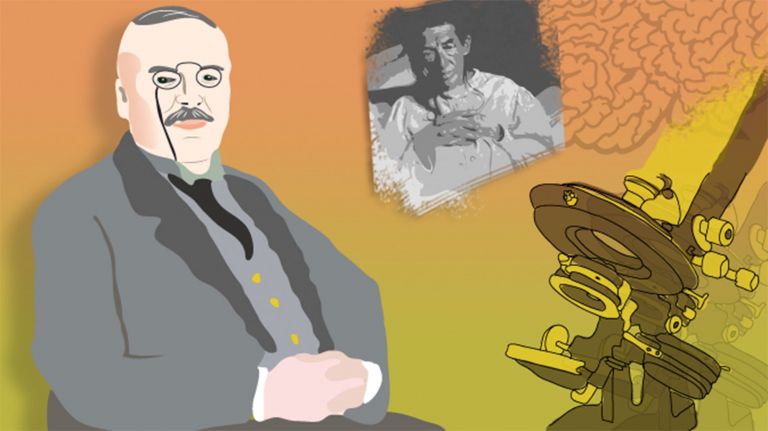

- In 1961, after conducting several animal experiments, American neurobiologist Roger Sperry was one of the first to sever the connection between the two hemispheres of the brain in a human being: the corpus callosum.

- This operation was intended to prevent seizures from spreading from one Hemisphere of the brain to the other in patients with severe epilepsy. The procedure is still used today for epilepsy patients.

- Sperry spent years researching the consequences of severing the Corpus callosum for patients and what this revealed about the specialization of the brain hemispheres. For this, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1981.

Hemisphere

The cerebrum and cerebellum each consist of two halves – the right and left hemispheres. In the cerebrum, they are connected by three pathways (commissures). The largest commissure is the corpus callosum.

Corpus callosum

As the largest commissure (connection in the brain), the corpus callosum connects the two cerebral hemispheres. It consists of 200-250 million nerve fibers and serves to exchange information.

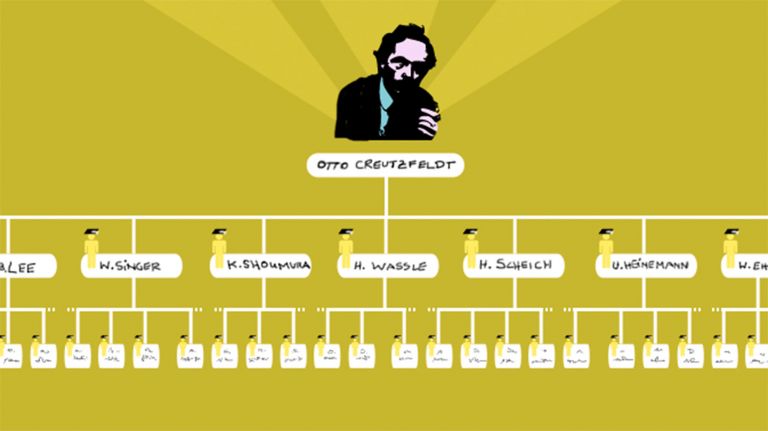

“Some of Sperry's admirers believe that he received the Nobel Prize for the wrong work or that he even deserved a second prize,” wrote neurophysiologist Bernice Grafstein in a portrait of Roger Sperry. Sperry's actual research interest was how the organization of the nervous system manifests itself in behavior – the split-brain operations were only one part of this, a means to an end. Sperry worked primarily with monkeys, fish, cats, rats, and salamanders. For example, Sperry rerouted motor nerve pathways that stimulated the left foot of a rat. This foot then moved when the other foot – the right one – was stimulated. Neither experience nor training could change the inappropriate response. In another experiment, Sperry swapped the nerve fibers for the muscles in the hind legs. As a result, the leg stretched instead of buckling when the foot was injured. In salamanders, Sperry cut the optic nerves and rotated the eyeballs 180 degrees. In salamanders, the optic nerves grew back – but for the rest of their lives, the animals saw everything upside down. The nerve connection was restored under genetic control.

The early 1960s at the White Memorial Medical Center in Los Angeles: a screeching saw opens the skull. Thin tweezers work their way inch by inch into the groove between the two hemispheres of the brain and encounter resistance so slight that it feels as if the instrument is piercing soft butter. However, the resistance is the connection between the two hemispheres of the brain: the ▸ Corpus callosum is being cut through. 200 million nerve fibers are being severed in the process.

American neurobiologist Roger Sperry was one of the first to sever the connection between the hemispheres in the brains of people suffering from epilepsy. “The fact that we can now actually help patients with particularly severe epilepsy is thanks to Roger Sperry,” says Karl Rössler, neurosurgeon and senior physician at Erlangen University Hospital. However, severing the Corpus callosum sounds more dramatic than it really is. “On the one hand, such an operation, called a callosotomy, is performed only about a dozen times a year in Germany. On the other hand, it helps patients by preventing electrical impulses from being transmitted from one Hemisphere to the other during an epileptic seizure.”

As Roger Sperry noted, patients with split brains were finally able to live without the sometimes life-threatening seizures after the operations. However, some of these so-called split-brain patients now behaved strangely, reported Sperry's assistant Michael Gazzaniga: In one patient, the right hand wanted to pull up the pants, while the left hand wanted to pull them down. In another case, a man was angry with his wife and attacked her with his left hand, while his right hand tried to protect her at the same time. And when another patient was asked what he wanted to be when he grew up, the man first wrote “race car driver” with his left hand and then “design engineer” with his right hand.

Corpus callosum

As the largest commissure (connection in the brain), the corpus callosum connects the two cerebral hemispheres. It consists of 200-250 million nerve fibers and serves to exchange information.

Hemisphere

The cerebrum and cerebellum each consist of two halves – the right and left hemispheres. In the cerebrum, they are connected by three pathways (commissures). The largest commissure is the corpus callosum.

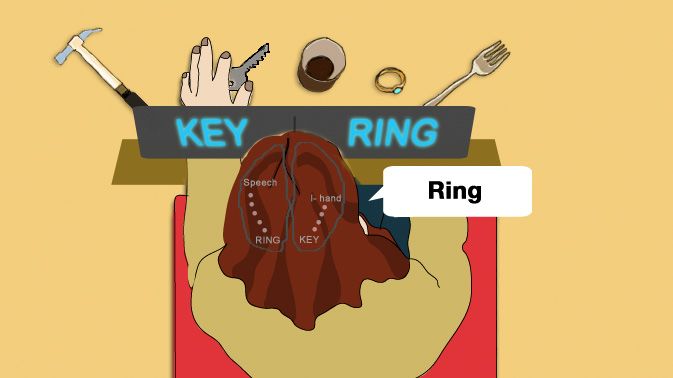

One brain becomes two

Sperry and Gazzaniga then developed tests to investigate the consequences of split-brain operations in more detail. They placed the patients in front of two screens. The patients first had to fix their gaze on a point in the middle. Then they were briefly shown the image of a cup on the right-hand screen. The patients reported seeing a cup. However, when an image of a fork appeared on the left screen, they were unable to name it. With their left hand, however, they were able to write down the word, type the correct word in a list, or find the fork by feeling among several covered objects. When the patients were then asked what they had written down, they had no idea.

Sperry concluded that the two halves of the brain are highly specialized. The left side is more responsible for analytical and linguistic tasks, while the right side is better at spatial Perception and music. Today, it is widely known that the two hemispheres of the brain have different specializations and that many functions in the brain are cross-wired. For example, the contents of the left visual field are processed in the right hemisphere, and right-handed people write with the left Hemisphere of the brain. In split-brain patients, however, the two hemispheres can no longer communicate with each other. Information from the left visual field thus only reaches the right hemisphere of the brain. It is all the more astonishing that patients were still able to associate the fork presented only in the left visual field with a term on a list: their right hemisphere was not “word-blind” or “word-mute” after all – just not as linguistically gifted as the left hemisphere.

A good half a century ago, these discoveries by Roger Sperry, his assistant Gazzaniga, and neurosurgeon Joseph Bogen were revolutionary. “The neurological doctrine at the time was so strong that Dr. Bogen felt compelled to remove his name from our first scientific paper on the language of split-brain patients for the sake of his conscience,” Roger Sperry later said.

Perception

The term describes the complex process of gathering and processing information from stimuli in the environment and from the internal states of a living being. The brain combines the information, which is perceived partly consciously and partly unconsciously, into a subjectively meaningful overall impression. If the data it receives from the sensory organs is insufficient for this, it supplements it with empirical values. This can lead to misinterpretations and explains why we succumb to optical illusions or fall for magic tricks.

Hemisphere

The cerebrum and cerebellum each consist of two halves – the right and left hemispheres. In the cerebrum, they are connected by three pathways (commissures). The largest commissure is the corpus callosum.

Recommended articles

Patience leads to the Nobel Prize

Sperry himself remained undeterred. He was convinced of his work – and patient. He is said to have sat in his office for days on end, his feet up on the table, staring into space – thinking. Scientific papers are said to have lain in his drawer for years because Sperry wanted to conduct further tests first in order to substantiate his arguments for discussion.

Finally, in 1981 – 20 years after the first split-brain operation on a human being – Sperry was honored with a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine “for his discoveries concerning the functional specialization of the cerebral hemispheres,” the committee explained. In an almost ironic twist of fate, Roger Sperry received only half a Nobel Prize – the other half went to David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel, two neurobiologists who had studied the visual Perception system.

“The great pleasure and feeling in my right brain are more than my left brain can find the words to tell you,” were the words with which Sperry ended his Nobel Prize speech. However, he did not deliver it himself, but had a colleague read it out because he was unable to attend the Nobel Prize ceremony in Sweden for health reasons.

On a personal level, Sperry was considered grumpy, taciturn, and soon also a little strange. Photos from that time show a thin man with thinning hair and a white beard. “Those who didn't know him well assumed that he had become religious, like so many other old people,” reports his colleague and neurosurgeon Bogen from a party in honor of Sperry's award.

After all, Sperry was now 68 years old and philosophized about how the brain, perception, and reality were connected. Sperry believed that consciousness was closely intertwined with the brain but could not be reduced to it. Ultimately, it had properties that could not be explained by the properties of the brain. A few years after the Nobel Prize party, even the older professors, who had been Sperry's friends for almost 40 years by then, gave up trying to defend or at least understand “the philosophy of his later years.”

Perception

The term describes the complex process of gathering and processing information from stimuli in the environment and from the internal states of a living being. The brain combines the information, which is perceived partly consciously and partly unconsciously, into a subjectively meaningful overall impression. If the data it receives from the sensory organs is insufficient for this, it supplements it with empirical values. This can lead to misinterpretations and explains why we succumb to optical illusions or fall for magic tricks.

How it all began

Sperry's amazing life journey was not yet foreseeable on August 20, 1913, when he was born in Connecticut. His father was a banker and his mother taught at a vocational school. When Sperry was eleven years old, his father died and his mother moved to the local high school. Sperry was athletic, played baseball and American football, and was captain of the basketball team. At the same time, he was so well educated that he received a scholarship to Oberlin College in Ohio. Here he was able to pursue his second passion: 17th-century English poetry. In 1935, Sperry received a bachelor's degree in English. He added two years of psychology studies, then switched to zoology and received a doctorate in Chicago in 1941. He then conducted research at the elite Harvard University and finally came to the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena in 1954. As early as the late 1950s, Roger Sperry and his doctoral student Ronald Myers severed the hemispheres of cats to study the function of the corpus callosum.

When Sperry died on April 17, 1994, highly decorated, married, and the father of two children, the procedure for severing the Corpus callosum had long since been refined. “In epilepsy patients, almost the entire corpus callosum is still severed,” says neurosurgeon Rössler. “However, we now also use the procedure for tumors in the cerebral ventricle system, i.e., inside the brain. The gap and the corpus callosum between the two hemispheres of the brain give us good access to the tumors.” So it is not a question of severing the corpus callosum, but rather of damaging as few fibers as possible. A half-centimeter incision is sufficient, and then the slit is widened to two to three centimeters, which is what is needed for access. The procedure is not dangerous, and patients do not change like Sperry's split-brain patients, says Rössler. His conclusion: “Sperry really did set a milestone for neurosurgery.”

Corpus callosum

As the largest commissure (connection in the brain), the corpus callosum connects the two cerebral hemispheres. It consists of 200-250 million nerve fibers and serves to exchange information.

Further reading

- Website on Roger Sperry; URL:http://rogersperry.org/ [as of 03/2002]; to the website.

- Roger Sperry and the 1981 Nobel Prize; URL: http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1981/index.html [as of 01/28/2013]; to the website