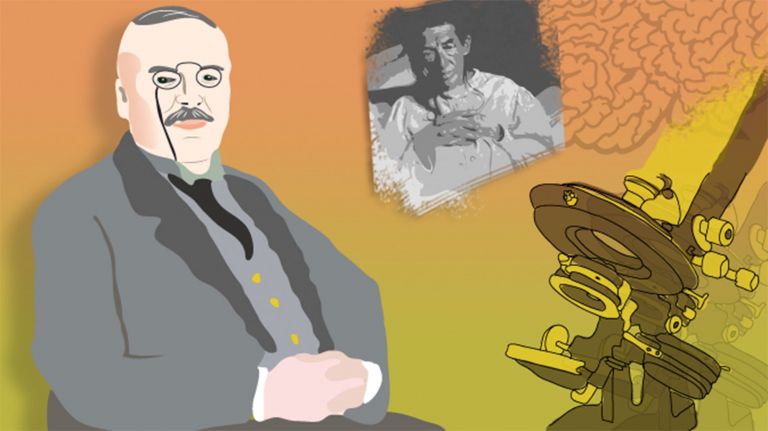

Thomas Willis: Founder of modern Neurology

English physician and neuroanatomist Thomas Willis wanted one thing above all else: to describe God's natural creations. The result was the most accurate studies of the brain and nervous system of his time.

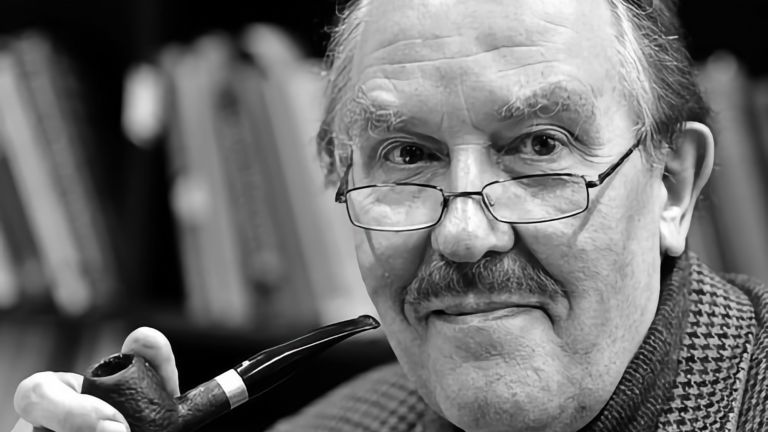

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Ortrun Riha

Published: 30.06.2016

Difficulty: intermediate

- With his research, physician and neuroanatomist Thomas Willis wanted to describe God's natural creations.

- Willis' best-known achievement is probably his functional description of the arterial ring of the brain named after him, which ensures the blood supply to the brain.

- His classification of ten cranial nerves was not replaced until 1788 by Samuel Thomas von Soemmerring's classification of 12 cranial nerves

- He achieved his groundbreaking results with the help of new techniques. He preserved brains in pure alcohol and, with the help of colleagues, also used innovative staining techniques.

- Thomas Willis is now considered the founder of neurology. His precise observations, which combined neuroanatomy, pathology, and clinical disorders into an overall picture, were groundbreaking.

cranial

A positional term – cranial means "towards the head." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction along the neural axis, i.e., forward.

In animals (without upright gait), the designation is simpler, as it always means forward. Due to the upright gait of humans, the brain bends in relation to the spinal cord, where cranial also means "upward."

Since the publication of Willis's important work Cerebri Anatome, many authors have expressed doubts about its authorship. They claim that Willis was merely a fashionable physician who lent his well-known name to the publication of the book. The actual research was primarily carried out by Richard Lower and Christopher Wren. In fact, Willis made no secret of the fact that he owed a great deal to Lower and Wren in his foreword to the book. However, doubts about Willis' contribution have since been compromised.

Thomas Willis' work is characterized by great diversity: he wrote about fermentation and fever, and was the first to describe restless legs syndrome. His clinical observations include the discovery that the urine of diabetics is sweet. He also made an important contribution to the description of neurological and psychiatric disorders such as epilepsy. He was particularly interested in researching the connection between anatomical changes in nerve structures and psychiatric disorders.

It is cold on December 14, 1650. Everything is ready for the autopsy of Anne Greene's corpse. Shortly before, the 22-year-old servant girl, convicted of infanticide, had dangled from the gallows for 30 minutes before being declared dead. As was customary at the time, the body was made available to the anatomy department. As the physician Thomas Willis was about to make his first incision, he heard strange noises coming from the dead woman's throat. Willis and his colleague William Petty decided on the spot to attempt resuscitation. With great effort, they actually succeeded in bringing Anne Greene back to life.

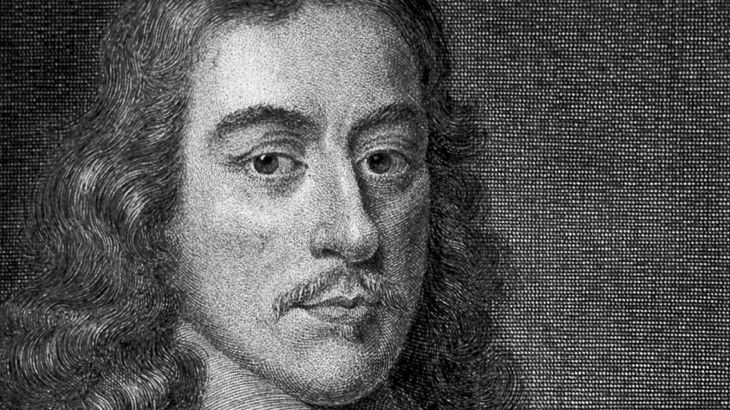

This incident made Thomas Willis (1621–1675) famous overnight, and shed light on his outstanding approach to researcher. The physician and neuroanatomist combined medical experience with first-hand anatomical knowledge. Instead of blindly trusting the booklore of recognized authorities, as was still common in medieval scholasticism, Willis, as a man of the modern age, regarded nature itself as his teacher.

Between tradition and new beginnings

Thomas Willis came into the world on January 27, 1621, shortly after the deaths of Shakespeare and Queen Elizabeth I. He was born in Great Bedwyn, England, a village in Wiltshire not far from London. His father, who had previously been in the service of various noblemen, settled as a farmer near Oxford.

In 1637, Willis enrolled at Christ Church College in Oxford, an educational institution with a rather traditional reputation. The future neuroanatomist originally wanted to pursue a clerical career. He therefore began studying the liberal arts, which at that time served as preparation for higher studies in theology, jurisprudence, and medicine. Here, Willis came into contact with the spirit of the Middle Ages, especially that of scholasticism. This meant above all understanding the proven authorities of antiquity, such as Aristotle. To earn money, Willis worked part-time as a servant for a clergyman. He helped the cleric's wife prepare medicines, which he was obviously quite skilled at and developed a Taste for.

The medical studies that Willis later decided to pursue were backward at Oxford. For many years, students had to study scientifically outdated literature from Hippocrates to Galen. But Willis was lucky. Shortly before he began his studies, there was a change in the curriculum, and suddenly autopsies were also occasionally on the program. However, Willis began his medical studies just as the English Civil War broke out. He sided with King Charles I of England and joined an auxiliary regiment against the king's opponents, the supporters of the English Parliament. It is possible that Willis also met the royal physician William Harvey (1578-1657) during this time, the discoverer of blood circulation and one of the most important representatives of experimental anatomy.

For his loyalty to the king, Willis was rewarded with a bachelor's degree in medicine in 1646, despite interrupting his studies, and was able to open his own practice near Oxford. Still inexperienced and unknown, he had to offer his services at markets and to landowners in the surrounding area. However, Willis also pursued research and established contacts with respected colleagues, scientists, and artists in nearby Oxford, including the chemist Robert Boyle (1627–1692). For the budding scientist, the supposed disadvantage – the brevity of his medical studies – proved to be a stroke of luck: Willis was not bound by tradition, but turned to modern experimental methods, which were flourishing at the time.

In 1657, he married Mary Fell, a close relative of the dean of Christ Church College in Oxford, who would bear him eight children. Willis was now a respected and wealthy physician who traveled widely. On his tours, he used to ride on horseback, dozing or even sleeping; an assistant accompanied him. If reports about him are to be believed, he was a pious man who treated the poor for free, but seemed rather ordinary, unfriendly, and unsociable. In 1660, he not only obtained his doctorate in medicine, but also became professor of natural philosophy at the University of Oxford.

Taste

The sensory impression we refer to as "taste" results from the interaction between our senses of smell and taste. In terms of sensory physiology, however, "taste" is limited to the impression conveyed to us by the taste receptors on the tongue and in the surrounding mucous membranes. It is currently assumed that there are five different types of taste receptors that specialize in the taste qualities sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami. In 2005, scientists also identified possible taste receptors for fat, whose role as a distinct taste quality is still being investigated.

stroke

Cerebral apoplexy

In a stroke, the brain or parts of it are no longer supplied with sufficient blood, which impairs the supply of oxygen and glucose. The most common cause is a blockage in an artery (ischemic stroke), less commonly a hemorrhage (hemorrhagic stroke). Typical symptoms include sudden visual disturbances, dizziness, paralysis, speech or sensory disturbances. Long-term consequences can include various sensory, motor, and cognitive impairments.

Recommended articles

New methods bring new insights

Before Willis appeared on the historical scene, neuroanatomical knowledge and examination methods were relatively modest. Willis' predecessors opened the skull and carefully removed the soft brain tissue. This allowed them to meticulously study the ventricles filled with cerebrospinal fluid, which at the time were believed to be the seat of the human mind. However, it was difficult for them to discern the intricate anatomy of the brain stem, for example.

Willis, on the other hand, broke new ground. For his brain studies, he was the first to use a brand-new technique developed by astronomer and architect Christopher Wren (1632–1723) for the preparation of zoological objects: Willis placed the object of his interest in pure alcohol to preserve it from rapid decay and to fixate it. This allowed him to remove the brain in one piece and make precise cuts. He examined the samples through a magnifying glass.

In Willis' time, during the Baroque period of the 17th century, the prevailing belief was that the end of the world was imminent, to be followed by a thousand-year reign of Christ. People wanted to study God's work in nature in order to learn more about the Creator and prepare for the arrival of Christ. For Willis, neuroanatomy was able to “unlock the secret places of the human mind and look into the living and breathing chapel of God”. He regarded the brain as a “harmonious and interconnected system created by God”. In a very modern way – and unlike many of his predecessors – he located higher mental functions not in the ventricles, the cavities filled with cerebral fluid, but in the convolutions of the cerebral cortex.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Comparative studies and revolutionary techniques

In his research, Willis attempted to show that animals and humans were similar in many ways in terms of brain architecture. Unlike animals, humans were believed to have an immortal soul, the rational soul, which endowed them with higher mental abilities. But Willis firmly believed that both animals and humans had a “bodily soul” that was responsible for basic biological functions such as movement and sensation. He located this in the Cerebellum and attempted to prove it through animal experiments. For example, he severed both vagus nerves in a dog, which then suffered “severe heart tremors”. The animal lived for several more days without being able to move or eat. After its death, Willis found large amounts of clotted blood in the heart and blood vessels.

Willis's most important book, Cerebri anatome from 1664, on the anatomy of the brain and nervous system was primarily a work of comparative anatomy. This was because the physician also dissected dogs, sheep, horses, and other animals. The book presented the first relatively detailed description and illustration of the neural structures of the brain in medical history.

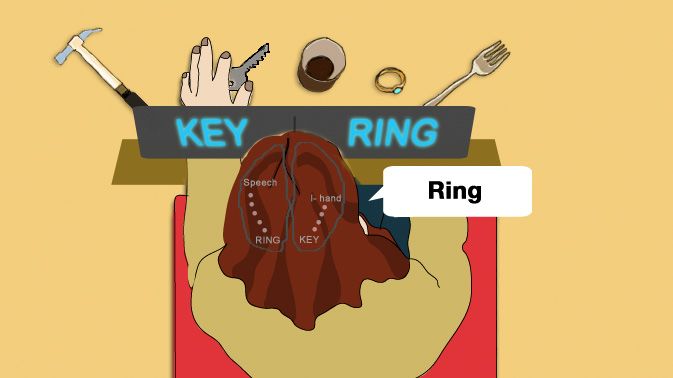

His two colleagues, Christopher Wren (1632–1723) and Richard Lower (1631–1691), who were themselves important scientists, offered him more than just active support, especially with the drawings. Wren and Lower also injected dye into the arteries of animals immediately after death. In this way, they laid the foundation for Willis' discovery of blood flow in the cerebral arteries. Willis reported how he and his colleagues “repeatedly injected a liquid containing dye into the arteries of the carotid artery of animals” so that the “blood vessels that creep into every corner and hidden place of the brain were saturated with the same dye.” Using these methods, he was able to determine the function of the arterial ring of the brain named after him, the Circulus arteriosu (cerebri), also known as the Circulus Willisi: it ensured the blood supply to the brain.

In 1666, Willis moved to London, where he continued his research until the end of his life and ran a successful medical practice. He died of pneumonia on November 11, 1675.

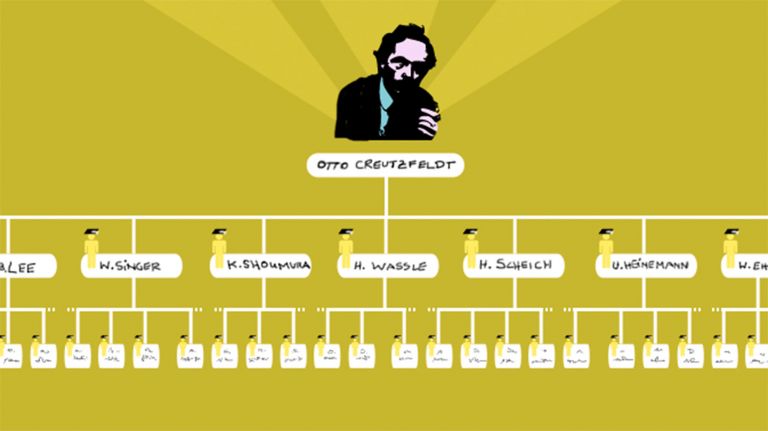

Today, Thomas Willis is considered the founder of neurology. Not only was he the first to use this term in his work, but he also introduced terms that are still used today, such as corpus striatum, claustrum, and optic thalamus. His numbering of ten pairs of cranial nerves was not replaced until 1788 by Samuel Thomas Soemmerring's (1755–1830) description of 12 cranial nerves, which is still valid today (however, these are not entirely correct: cranial nerves I and II – the Optic nerve and olfactory nerve – are essentially fiber tracts of the brain). He was not only the first to use this term in his work, but his precise observations, which combined neuroanatomy, pathology, and clinical disorders into an overall picture, were also groundbreaking. Willis based his findings on case histories of patients whom he dissected after death in order to find anatomical explanations for their symptoms. He was the first to describe myasthenia gravis, restless legs syndrome, and brain changes in congenital neurological disorders.

The eminent neurophysiologist and Nobel Prize winner Charles S. Sherrington (1857–1952) summed up Willis's achievements as follows: “Willis went to nature itself. He established the modern basis for the brain and nervous system, as far as that could ever be done.”

Cerebellum

Cerebellum

The cerebellum is an important part of the brain, located at the back of the brain stem and below the occipital lobe. It consists of two cerebellar hemispheres covered by the cerebellar cortex and plays an important role in motor processes, among other things. It develops from the rhombencephalon.

cranial

A positional term – cranial means "towards the head." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction along the neural axis, i.e., forward.

In animals (without upright gait), the designation is simpler, as it always means forward. Due to the upright gait of humans, the brain bends in relation to the spinal cord, where cranial also means "upward."

Optic nerve

nervus opticus

The axons (long fiber-like extensions) of the retinal ganglion cells form the optic nerve, which leaves the eye at the back of the optic disc. It comprises approximately one million axons and has a diameter of approximately seven millimeters.

Further reading

- Arráez-Aybar LA et al.: Thomas Willis, a pioneer in translational research in anatomy (on the 350th anniversary of Cerebri anatome). J Anat. 2015 Mar;226(3):289 – 300. doi: 10.1111/joa.12273.