Hubel and Wiesel: Cutting the Lawn with Nail Scissors

Alone the brain floats in its cranial cavity. If it weren't for the senses, it would have no idea what is happening to it. But how does a stimulus become a perception? How, for example, does the brain generate a coherent image from light waves? David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel began investigating this problem in 1958 – and were awarded the Nobel Prize in 1981 for their findings.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Herbert Schwegler

Published: 26.09.2012

Difficulty: serious

- American David H. Hubel and Swede Torsten N. Wiesel met in Stephen Kuffler's laboratory in 1958. Together, they spent 20 years studying the visual system.

- Their discoveries include “simple” and “complex” cells, Eye dominance columns, hypercolumns, and – for color processing – blobs. They created fundamental knowledge about sensory processing that can be found in every textbook today.

- In 1981, both (together with Roger Sperry) received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine “for their discoveries concerning information processing in the visual Perception system.”

Eye

bulbus oculi

The eye is the sensory organ responsible for perceiving light stimuli – electromagnetic radiation within a specific frequency range. The light visible to humans lies in the range between 380 and 780 nanometers.

Perception

The term describes the complex process of gathering and processing information from stimuli in the environment and from the internal states of a living being. The brain combines the information, which is perceived partly consciously and partly unconsciously, into a subjectively meaningful overall impression. If the data it receives from the sensory organs is insufficient for this, it supplements it with empirical values. This can lead to misinterpretations and explains why we succumb to optical illusions or fall for magic tricks.

Seeing is almost a miracle: light in the form of its smallest particles, photons, falls on the light-sensitive cells of the Retina in the Eye. As with a camera, this creates an image that is upside down. It is also pixelated, because each individual cell of the retina covers a small area of the visual field. When stimulated, it sends a nerve impulse along the Visual pathway across the brain to the Primary visual cortex There, the signals are decoded pixel by pixel and assembled into an image of the outside world. But how exactly does information processing work?

Retina

The retina is the inner layer of the eye covered with pigment epithelium. The retina is characterized by an inverse (reversed) arrangement: light must first pass through several layers before it hits the photoreceptors (cones and rods). The signals from the photoreceptors are transmitted via the optic nerve to the processing areas of the brain. The reason for the inverse arrangement is the evolutionary development of the retina, which is a protrusion of the brain.

The retina is approximately 0.2 to 0.5 mm thick.

Eye

bulbus oculi

The eye is the sensory organ responsible for perceiving light stimuli – electromagnetic radiation within a specific frequency range. The light visible to humans lies in the range between 380 and 780 nanometers.

Visual pathway

The visual pathway refers to the network of nerve cells involved in visual perception. In mammals, it runs from the retinal ganglion cells in the eye – as the optic nerve to the optic chiasm, then as the visual tract – via the only switching point in the lateral geniculate nucleus to the primary visual cortex.

Primary visual cortex

area striata

The part of the occipital lobe whose primary inputs originate from the visual system. According to Brodmann, who originally divided the cerebral cortex into 52 areas in 1909, the primary visual cortex is area 17.

What happened before

Some things about the visual process were already known before Hubel and Wiesel entered the scene: In the retina, several Receptor cells – the Cones for color information, the Rods for light-dark and movement – are connected to a Ganglion cell via horizontal and Bipolar cells The Hungarian-born American neurologist Stephen Kuffler had already investigated how these cells respond to stimuli in 1950. Among other things, he discovered that they cover specific regions of the visual field: when a stimulus occurs here, the cell produces a whole salvo of electrical impulses.

The axons of the ganglion cells form the Optic nerve of the respective Eye. Both cross at the optic chiasm, exchanging around 50 percent of their fibers. They then reach the lateral geniculate Nucleus of the thalamus (corpus geniculatum laterale, or CGL for short), the only switching station between the Retina and the Cortex. Irish scientist Gordon Morgan Holmes and English scientist Henry Head had already investigated the function of the CGL in 1908: its cells also respond to point-like light stimuli – just like the rods and cones of the retina.

The information travels further via the optic radiation directly to the Primary visual cortex (V1), where processing begins. But “no one had any clear idea how to interpret this bucket-brigade-like handing on of information from one stage to the next,” David Hubel later wrote. The few scientists who had attempted to unlock the secrets of V1 in the 1950s had discovered nothing illuminating. In retrospect, Hubel was not surprised: the cells in V1 “...were far too selective to pay Attention to something as coarse as diffuse light.”

Receptor

A receptor is a protein, usually located in the cell membrane or inside the cell, that recognizes a specific external signal (e.g., a neurotransmitter, hormone, or other ligand) and causes the cell to trigger a defined response. Depending on the type of receptor, this response can be excitatory, inhibitory, or modulatory.

Cones

The cones are a type of photoreceptor in the retina. The three different types of cones – S, M, and L – are each stimulated by short, medium, and long wavelengths of visible light, enabling color vision. They are highly concentrated in the fovea and enable sharp vision.

Rods

The rods are light-sensitive cells with high light sensitivity. They react even to weak light and are therefore responsible for scotopic vision, black-and-white vision, and vision at dusk. The rods are concentrated in the outer areas of the retina and therefore do not provide high visual acuity.

Ganglion

Term for a cluster of nerve cell bodies in the peripheral nervous system. The term nerve node is often used because of its appearance. (Greek gágglion = knot-like)

Ganglion cell

The ganglion cell bundles the signals from the photoreceptors in the retina and transmits them via its axons (long, fiber-like extensions of a nerve cell. All of these axons together form the optic nerve.

Bipolar cells

The bipolar cell is a bipolar neuron, i.e., a neuron with one axon and one dendrite located in the middle layer of the retina. It transmits sensory information from the photoreceptors to the ganglion cells.

Optic nerve

nervus opticus

The axons (long fiber-like extensions) of the retinal ganglion cells form the optic nerve, which leaves the eye at the back of the optic disc. It comprises approximately one million axons and has a diameter of approximately seven millimeters.

Eye

bulbus oculi

The eye is the sensory organ responsible for perceiving light stimuli – electromagnetic radiation within a specific frequency range. The light visible to humans lies in the range between 380 and 780 nanometers.

lateral

A positional term – lateral means "towards the side." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction at right angles to the neural axis, i.e., to the right or left.

Nucleus

In cell biology, the nucleus in a cell is the cell nucleus, which contains the chromosomes, among other things. In neuroanatomy, the nucleus in the nervous system refers to a collection of cell bodies – known as gray matter in the central nervous system and ganglia in the peripheral nervous system.

Retina

The retina is the inner layer of the eye covered with pigment epithelium. The retina is characterized by an inverse (reversed) arrangement: light must first pass through several layers before it hits the photoreceptors (cones and rods). The signals from the photoreceptors are transmitted via the optic nerve to the processing areas of the brain. The reason for the inverse arrangement is the evolutionary development of the retina, which is a protrusion of the brain.

The retina is approximately 0.2 to 0.5 mm thick.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Primary visual cortex

area striata

The part of the occipital lobe whose primary inputs originate from the visual system. According to Brodmann, who originally divided the cerebral cortex into 52 areas in 1909, the primary visual cortex is area 17.

Attention

Attention

Attention serves as a tool for consciously perceiving internal and external stimuli. We achieve this by focusing our mental resources on a limited number of stimuli or pieces of information. While some stimuli automatically attract our attention, we can select others in a controlled manner. The brain also unconsciously processes stimuli that are not currently the focus of our attention.

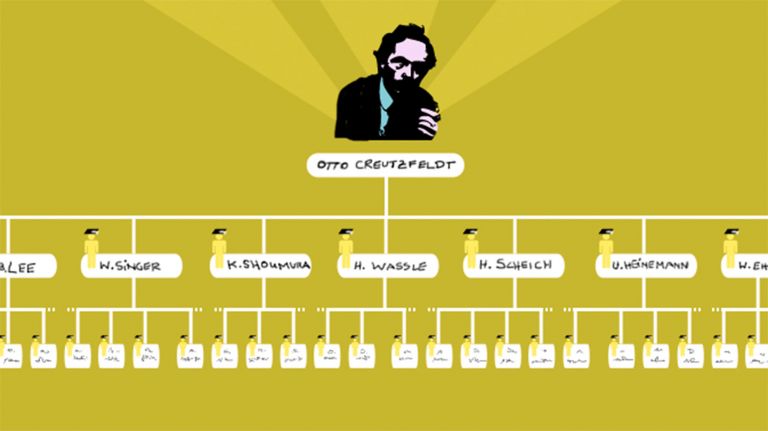

David Hunter Hubel

Hubel met Torsten Wiesel in Kuffler's laboratory in 1958 – a Swede and a... Canadian? American? David Hubel was born in Ontario in 1926. That made him Canadian, which is why he had to serve in the Canadian training corps during the final phase of World War II. However, since his parents were American, he was drafted into the US Army in 1954 and served at Walter Reed Hospital. The Royal Society later stumbled upon this dual citizenship and did not know whether to accept him as a regular or foreign member.

Hubel was interested in science even as a child. This was reflected not only, but also, in his mixing of explosives. He studied physics and mathematics at McGill University in Montreal – not least so that he would have enough time to play the piano. More on a whim, he also applied to medical school – and was accepted. In the end, he decided to pursue medicine full-time. When he told his physics professor, the professor replied, “Well, I admire your courage – I wish I could say the same about your judgment.”

The physics professor was mistaken: at Walter Reed Hospital, Hubel began researching the Primary visual cortex of cats. To this end, he developed the modern metal microelectrode, which enabled him to measure the activity of individual cells.

Primary visual cortex

area striata

The part of the occipital lobe whose primary inputs originate from the visual system. According to Brodmann, who originally divided the cerebral cortex into 52 areas in 1909, the primary visual cortex is area 17.

Torsten Nils Wiesel

In his autobiography for the Nobel Foundation, Wiesel describes himself as a rather lazy, mischievous student who was more interested in sports than anything else. That did not prevent him from earning a doctorate in medicine at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm and going to Kuffler in New York in 1955.

As unremarkable as Wiesel's biography may have been in his younger years, he stood out in his later years for his commitment to human rights. He was nominated several times for a position at the National Institutes of Health but was rejected by the official in charge. The official was a Republican, and Wiesel had signed too many full-page advertisements in the New York Times against President Bush. The fact that he was also involved in the fight against climate change probably did little to improve his chances.

Recommended articles

Unexpected results

Wiesel was already at Kuffler's laboratory when Hubel joined. And Hubel brought not only the microelectrode in his toolbox, but also a method for attaching it to a cat's head. This enabled them to pursue the first big question: if the cells of the CGL respond to point-like light stimuli in the same way as those of the retina, how do cells in the Primary visual cortex respond?

The first successful derivation of a cell in V1 did not really start off promisingly. Although the microelectrode was stable, no matter what stimulus Hubel and Wiesel offered it, the cell remained silent. “We tried everything short of standing on our heads to get it to fire,” Hubel wrote. It took hours to find the Retinal region that corresponded to it. But even that didn't help much: the cell responded occasionally, but mostly not. So it took quite a long time for the two researchers to recognize a pattern. And it was completely surprising: the cell only responded when the faint shadow of an edge of the slide was moved through a specific region. But that wasn't all: the line of the shadow also had to be at a certain angle, i.e., have a specific orientation. In every other case, the cell remained silent.

Primary visual cortex

area striata

The part of the occipital lobe whose primary inputs originate from the visual system. According to Brodmann, who originally divided the cerebral cortex into 52 areas in 1909, the primary visual cortex is area 17.

Retinal

A chemical synthesized from vitamin A. Together with opsin, it forms rhodopsin.

Basic knowledge

The rest is well-known history, as can be found in any basic work on the brain today: Hubel and Wiesel had stumbled upon what they later called a “complex cell” that responds specifically to orientation and movement. In this case, the cell only responded when the light bar was at the 11 o'clock position and moved to the upper right. Complex cells make up an estimated three-quarters of the neurons in V1 and actually form the second stage of cortical processing. The first stage consists of “simple cells” that only respond to lines at a very specific angle. These simple cells are arranged in columns one above the other – the basis of a complex architecture.

What the textbooks don't mention is the effort Hubel and Wiesel had to put in: they were able to examine 200 to 300 cells per experiment – for which they had to locate the Receptive field and find the cell's preferred stimulus each time. Then they pushed the electrode a little deeper – they couldn't move it to the side because that would have destroyed the Cortex tissue. Hubel later compared this Sisyphean task to cutting a lawn with nail scissors.

There is no question that David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel deserved the 1981 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine “for their discoveries concerning information processing in the visual system.” The significance of their work can hardly be overestimated. Not only did it enable a detailed mapping of the visual cortex, it also provided the first insight into how the brain analyzes sensory information – with astonishing depth of detail. However, research continues. As Hubel said, “... we would be foolish to think that we had exhausted the list of possibilities.”

Receptive field

The receptive field is the area of the environment in which a stimulus changes (increases or decreases) the activity of a specific nerve cell.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².