Thomas Südhof: Many small Steps to the Nobel Prize

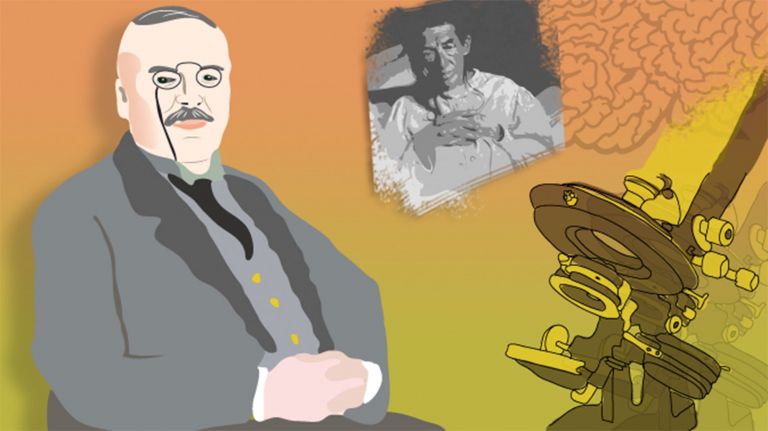

His colleagues attest to his extraordinary intellectual prowess. Thomas Südhof succeeded in deciphering an essential molecular mechanism in the synapses. For this, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2013.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Johann Helmut Brandstätter

Published: 03.12.2013

Difficulty: intermediate

- Thomas Südhof received the call from the Nobel Committee while he was on his way to a research meeting in Spain. The conversation was recorded.

- His colleagues were impressed by his intellectual prowess. He also had enormous stamina, spending almost around the clock in the laboratory.

- In the late 1980s, Thomas Südhof began to decipher the molecular machinery in synapses. In doing so, he brought together the most modern neurophysiological and molecular biological methods.

- He discovered many proteins that are essential for vesicles in synapses to release transmitters. Thanks to him, researchers now have a very accurate picture of how the molecular machinery in synapses works.

December 22, 1955 Thomas Südhof is born in Göttingen

1975-1982 Studies medicine at RWTH Aachen University, Harvard University, and the University of Göttingen

1982 Doctorate at the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry in Göttingen

1983-2008 Research and teaching at the University of Texas Health Science Center in Dallas, alongside three years at the Max Planck Institute for Experimental Medicine in Göttingen

Since 2008 Research and teaching at Stanford University

2013 Nobel Prize in Medicine

His cell phone rings as he is driving in Spain and has gotten a little lost. “Hello, Professor Südhof?” Thomas Südhof answers, not yet realizing that this is the call that probably every scientist has dreamed of receiving. “It has just been announced that you have been awarded the Nobel Prize, together with Jim Rothman and Randy Schekman.” The conversation was recorded, and you can hear the scientist's incredulous silence on the Nobel Committee's website. “Are you serious?” he stammers, and when he is convinced that it is not a joke, he exclaims with a laugh, “Oh my God!”

He stops his car, and shortly afterwards he has collected himself somewhat. It is a moment of honest emotion; that is probably why his tremendous professional self-confidence flashes through briefly. He is asked how he feels about being honored alongside James (Jim) Rothman and Randy Schekman. “It's wonderful,” he replies. “You know, everyone has their own view of who deserves something, and you tend to overestimate yourself.” However, he considers the award for his two colleagues and himself to be “more than fair.”

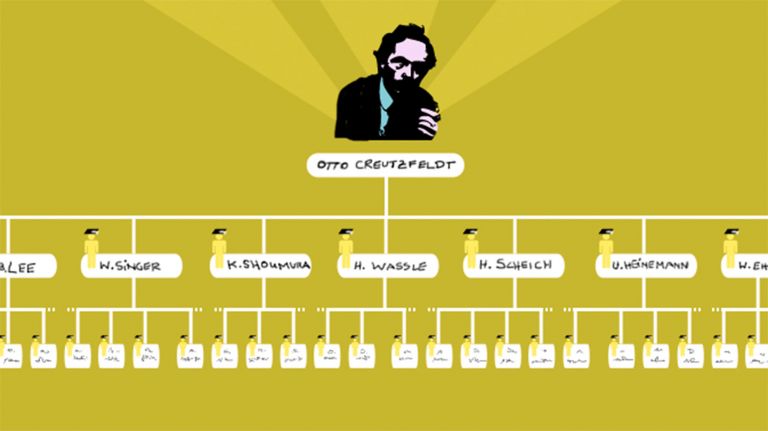

If you ask his colleagues, you will quickly come to the conclusion that Südhof has every reason to show this self-confidence. After all, he must be an impressive researcher. “Only two other colleagues I know have his intellectual clout,” says Nils Brose. The biochemist is now director of the Max Planck Institute for Experimental Medicine in Göttingen. In the early 1990s, he worked with Südhof when he was conducting research at the Southwestern Medical Center of the University of Texas in Dallas.

“An extraordinary cognitive ability”

He was quickly impressed by his boss: “He has an extraordinary cognitive ability.” As a postdoc at the time, Nils Brose worked very hard, putting in more than twelve hours every weekday and often working on weekends, as well. “I couldn't do any more than that, otherwise my wife would have left me. But Thomas Südhof worked far longer hours than I did, and he never tired of being astute.” People who display such obsession are often difficult to get along with, but that's clearly not the case with Südhof: “He never gets angry; he manages to objectify conflicts,” says Nils Brose. “That was very good for me as an employee; I always knew where I stood.”

Südhof displays this composure even at the moment of his greatest triumph. During the phone call in Spain, he was on his way to a small meeting of neuroscientists. By the time he arrived, news of his Nobel Prize had already spread, and his colleagues greeted him with a standing ovation. “Then he gave his scheduled lecture as if nothing had happened,” recalls Nils Brose. “He's not really the emotional type.”

He almost became a doctor

In the early 1980s, there was a moment in Südhof's life when he almost strayed from the path that would later lead him to the Nobel Prize. He had already completed his medical studies and doctorate in Germany and then achieved his first major successes in the laboratory of future Nobel Prize winners Joseph Goldstein and Michael Brown. But up until then, his goal had always been to practice medicine and give up basic research. Like his sister Gudrun, he wanted to follow in the footsteps of his father, who worked as a physician. But Joseph Goldstein and Michael Brown recognized Südhof's potential and began to persuade him.

“Their argument was that my scientific work could be more productive overall than if I spent a lot of time in the clinic,” Südhof recalled in the blog of his current alma mater, Stanford University. He changed his mind and soon after set up his own laboratory in Dallas.

However, he left the field of his mentors, the study of fat metabolism.

“As a medical student, I had worked with patients suffering from dementia or acute schizophrenia,” he recalls. “That left a deep impression on me.” At the time, he noted: "We understand pretty well how to build a bridge or an airplane. But no one knows how to deal with a mental or neuropsychiatric disorder. We are only at the beginning." So he decided to switch to neurophysiology.

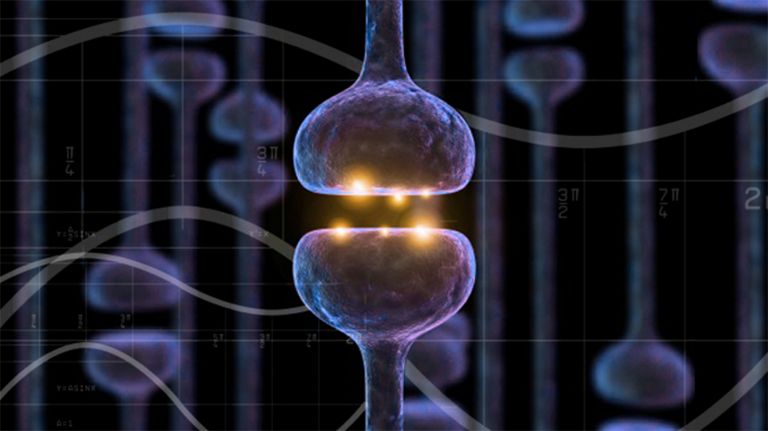

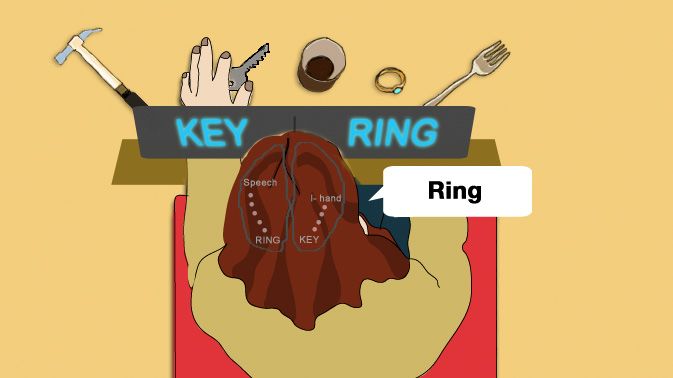

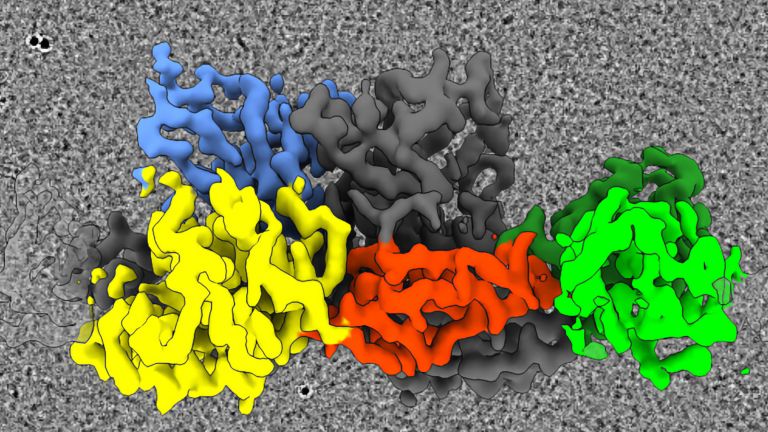

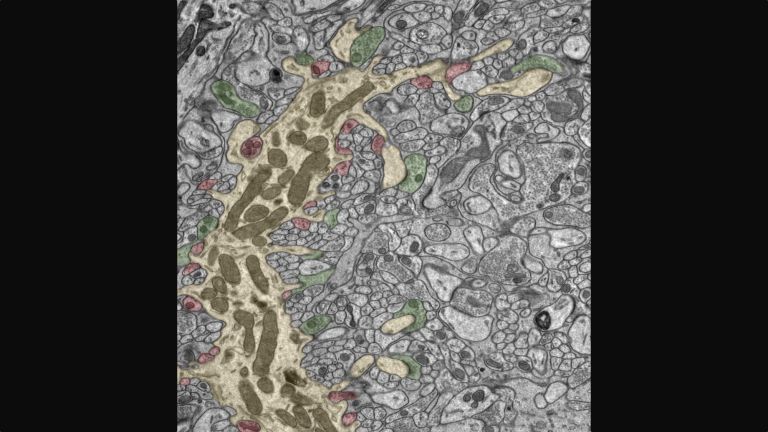

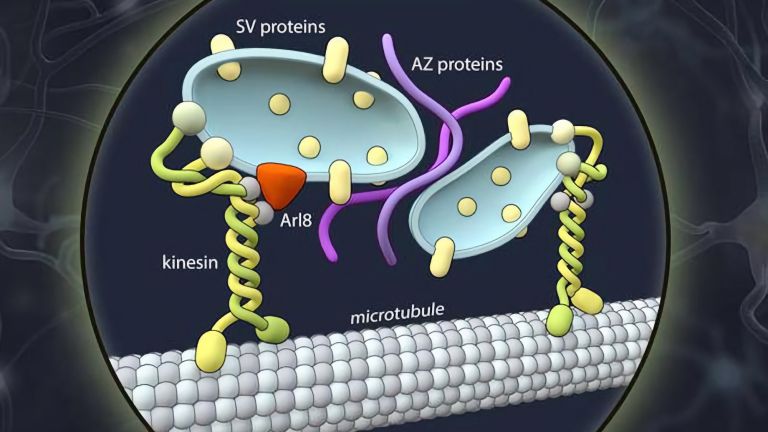

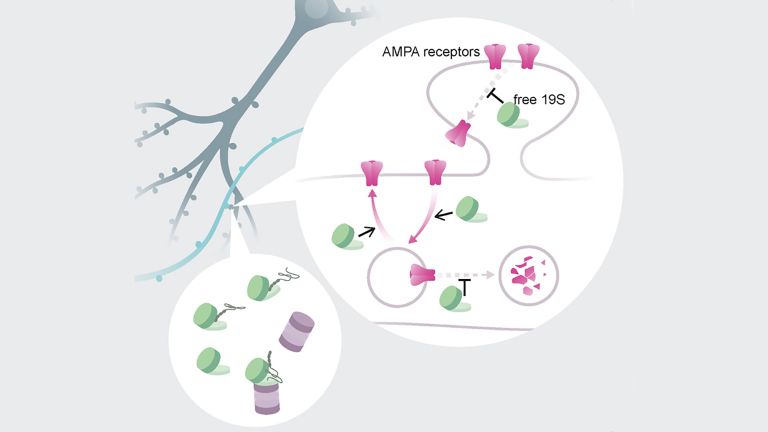

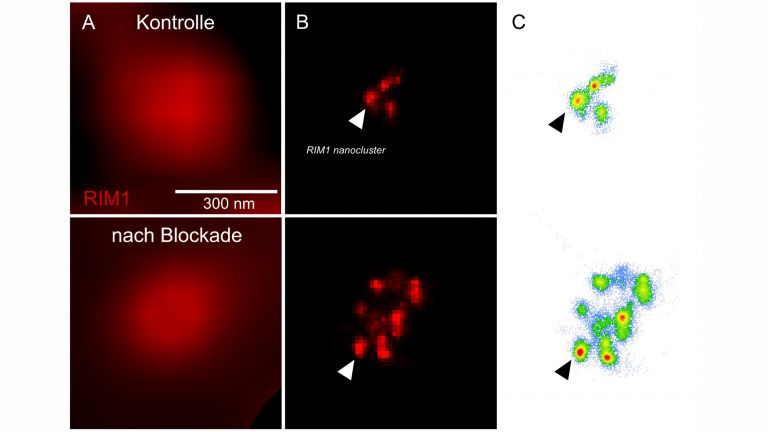

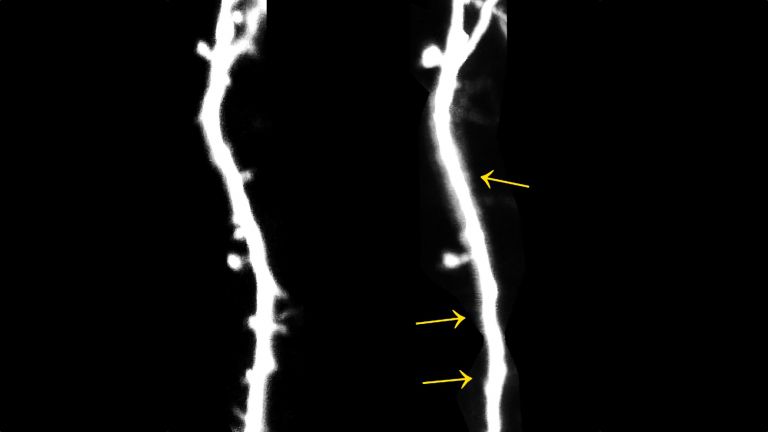

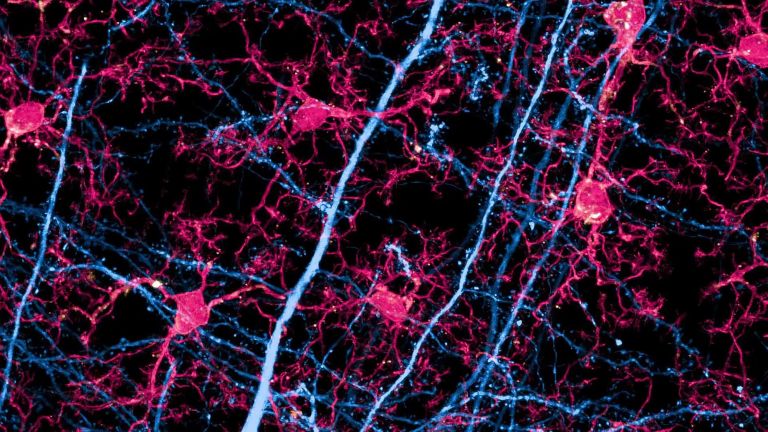

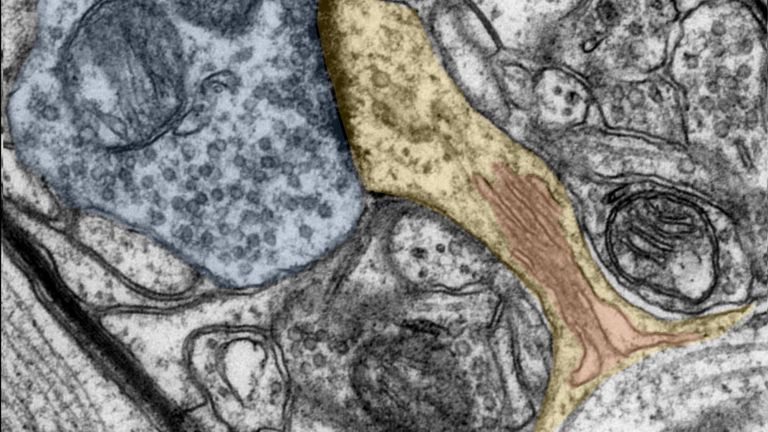

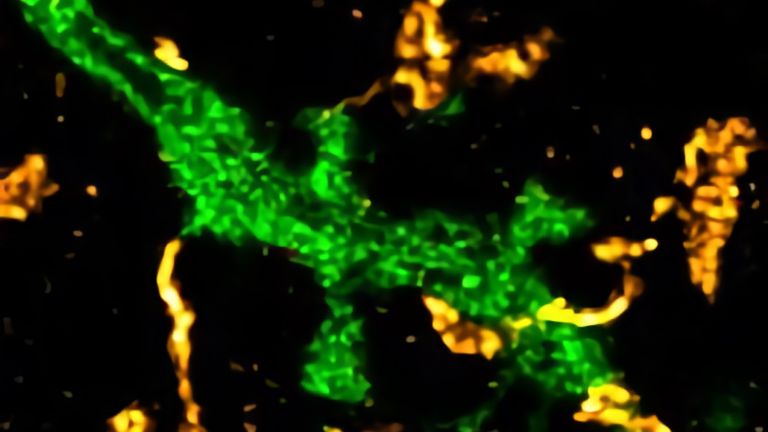

He had learned the latest molecular biology techniques from Joseph Goldstein and Michael Brown. He wanted to use these to understand the molecular machinery in the contact points of nerve cells, the synapses. The basic principle of synaptic transmission was already textbook knowledge: The electrical signal from a nerve cell causes small vesicles inside the cell to fuse with the cell membrane. This allows messenger substances (transmitters) to enter the synaptic cleft. These substances trigger an electrical signal in the neighboring nerve cell. This is how a stimulus is transmitted from one cell to the next.

Recommended articles

“A daring approach”

However, how this works at the molecular level was largely unknown at the time. Thomas Südhof asked himself: How does the electrical signal cause the vesicles to fuse with the membrane? “At the end of the 1980s, it was a daring approach to try to decipher the membrane fusion mechanism,” says Nils Brose in retrospect. “Because at that time, the components were not yet known.” So Südhof had to do detailed pioneering work and try to find as many proteins as possible that are involved in this process.

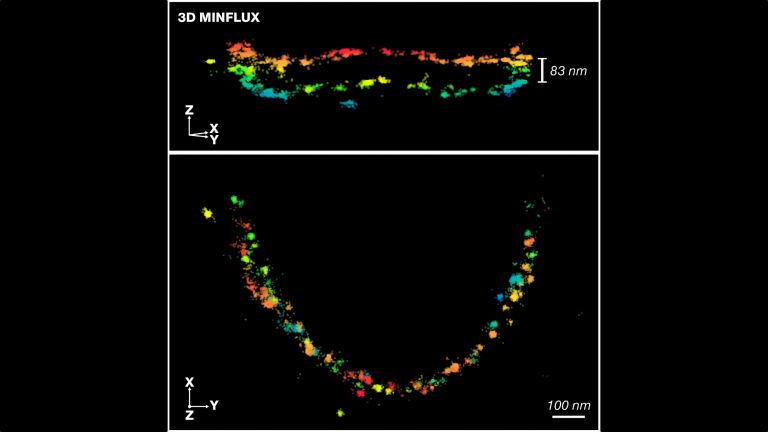

“What made his research special was – based on the findings of biochemistry – a great combination of electrophysiology and molecular biology,” says Felix Wieland, a biochemist at Heidelberg University who has himself conducted research into vesicle transport in cells. Südhof brought together all the cutting-edge techniques in biology at the time. With the rapidly advancing methods of molecular biology, he was able to identify many genes involved in transmitter release in the synapse. Using increasingly precise electrophysiological methods, he was able to determine the effects of these genes.

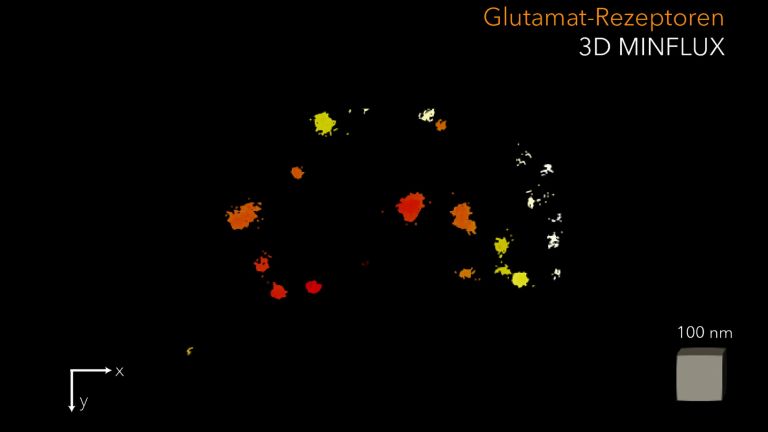

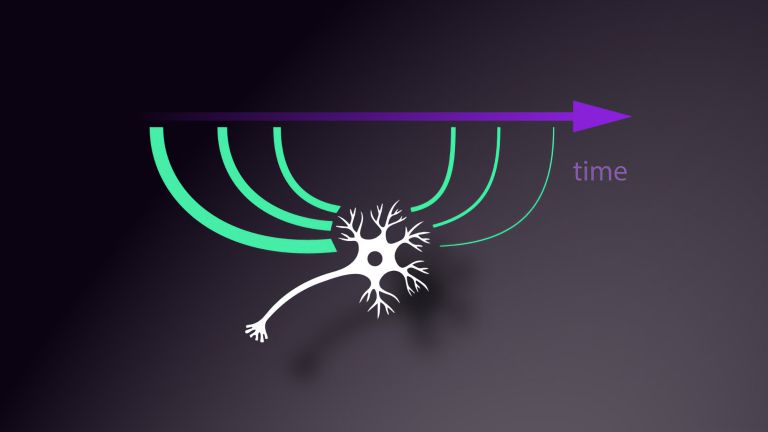

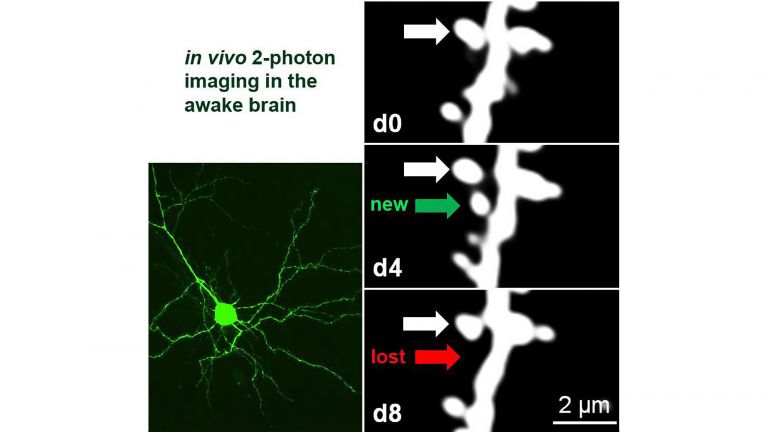

However, another technique was needed to bring these two tools together. “Thomas Südhof was the one who quickly recognized the importance of mouse mutants,” recalls Nils Brose. It had only recently become possible to selectively switch off genes in mice. This enabled Südhof to test the role of each gene he found in nerve cells. “This allowed him to show how calcium regulates transmitter release at the molecular level,” says Felix Wieland. Calcium ions play an essential role in synapses: they flow into the cell as soon as an electrical signal arrives. There they trigger a molecular chain reaction that causes the vesicles to fuse with the membrane and release the messenger substances. Südhof found many of the proteins involved in this process. As a result, scientists now have a precise spatial and temporal understanding of this molecular machinery.

Research without a eureka moment

However, Südhof was aware that our understanding of how the molecules interact in the synapses was still very rough. In a review article written in 2013, he states: “Only when we understand how synapses work, how synapses differ from one another, and how synapses change within milliseconds and years, can we also understand how the brain works, regardless of how many neural connections are mapped.”

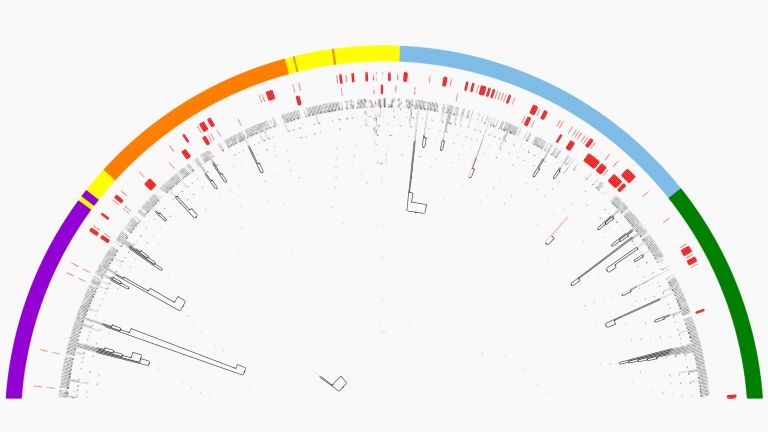

The Stanford blogger mentioned above asked Südhof what his eureka moments were – when he felt he had just made a breakthrough. Although he has made such important discoveries, Südhof could not name any such moments. In his experience, research now works step by step, not in leaps and bounds, he replied. “I firmly believe that most work progresses only gradually.” It was many small steps that ultimately led to the cell phone call on a Spanish street and the Nobel Prize that came with it.

Further reading

- The Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet: Scientific Background: Machinery Regulating Vesicle Traffic, A Major Transport System in our Cells. 2013; URL: http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/2013/advanced-medicineprize2013.pdf [Stand: 18.11.2013]; zur Webseite

- Südhof, TC: Neurotransmitter Release: The Last Millisecond in the Life of a Synaptic Vesicle. Neuron 2013;80(3):675 – 690 (zum Abstract).

![Das Verhalten von Vesikeln (Containerbläschen) in Zellen ist das Spezialgebiet der Medizin-Nobelpreisträger von 2013. Thomas Südhof entdeckte, auf welche Weise Calcium-Ionen die Freisetzung von Neurotransmittern steuern. Grafik: Meike Ufer [nach Informationen des Nobelkomitees, Mattias Karlén]](https://www.thebrain.info/sites/default/files/styles/scale_768_w/public/images/copy_of_4_3_15_Thomas_Suedhof_Ansicht.jpg?itok=YuPHHSte)