John Eccles: Across the Gap

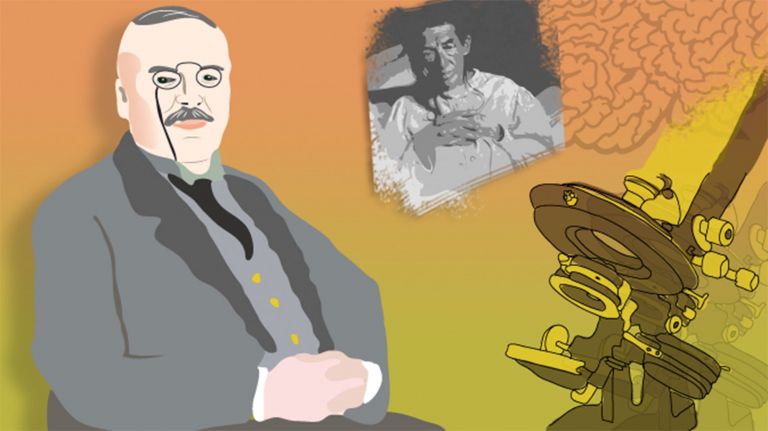

Only when he was prepared to abandon the theory he had held for decades did neuroscientist John Eccles achieve his decisive breakthrough. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for his research into synaptic transmission.

Scientific support: Dr. Fabio De Sio

Published: 06.06.2013

Difficulty: serious

- Using measurements within nerve cells, John Eccles was able to show that information is transmitted from neuron to neuron by chemical means.

- He discovered that, in addition to excitatory postsynaptic potentials, there are also inhibitory ones.

- Eccles was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1963, together with British physiologists Alan Hodgkin and Andrew Huxley, for his research on synaptic transmission.

- On the question of how the brain and mind are connected, he and philosopher Karl Popper advocated an interactionist dualism that remains controversial to this day.

January 27, 1903 John Eccles is born in Melbourne, Australia

1925 Graduates with a degree in medicine from Melbourne University

1925–1937 Studies and research at the University of Oxford

1937–1943 Research in Sydney

1944–1951 Professorship at the University of Otago in New Zealand

1952–1966 Professorship at the Australian National University in Canberra

1963 Eccles receives the Nobel Prize in Medicine together with Alan Hodgkin and Andrew Huxley

From 1966 onwards Research in the USA in Chicago and New York

1997 Eccles dies in Locarno, Switzerland

2007 The Australian National University founds the Eccles Institute of Neuroscience

The true greatness of a researcher is also demonstrated by their ability to recognize and correct a mistake. Australian neurophysiologist John Eccles did just that: for years, he passionately advocated a theory about how communication between nerve cells works. But then he disproved his own theories with experiments – and was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for his work.

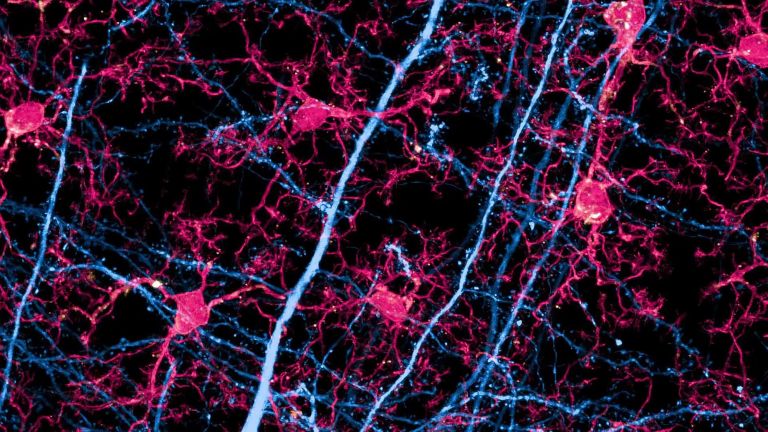

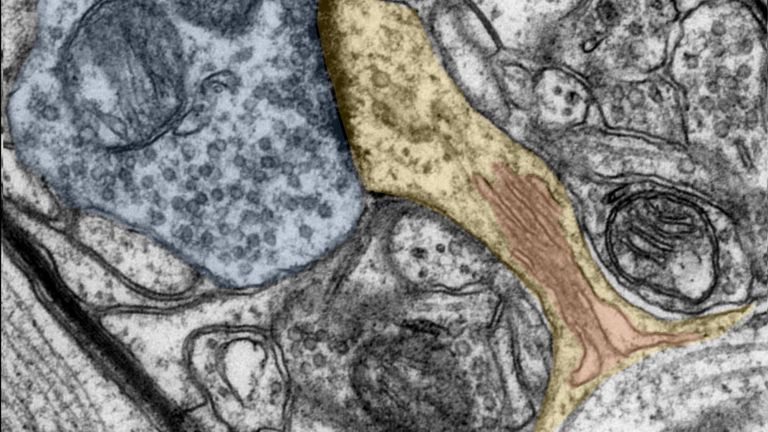

In the mid-1940s, Eccles was desperate because his scientific theory had been shaken. He was convinced that nerve cells communicated with each other purely electrically. It was already known at that time that information processing within neurons took place on the basis of voltage changes. So it was very logical to Eccles that electricity also played a decisive role at the contact points between two cells, the synapses. His idea was that when a neuron fires an action potential, this electrical signal arrives at the synapse. There is a synaptic cleft there, i.e., a gap to the downstream nerve cell. According to Eccles' idea, current also flows across this gap. In this way, the electrical signal reaches the next cell. As plausible as this theory sounded, research results refused to confirm it. Instead, there was growing evidence that messenger substances in the synapses are essential, meaning that signal transmission between nerve cells is chemical rather than electrical. As early as 1936, Henry Dale and Otto Loewi received the Nobel Prize for their discovery that nerves stimulate muscles by releasing the chemical acetylcholine.

Eccles, however, believed that transmission between nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord is far too fast to be chemical in nature. The dispute between the proponents of electrical and chemical transmission became increasingly bitter during these years. Once, at a conference in Cambridge, it even almost came to blows between Eccles and Henry Dale, a member of the opposing side. But more and more experiments supported the theory of Eccles' opponents. The normally energetic man gradually lost heart. He believed himself to be on the losing side. Eric Kandel describes this very vividly in his book In Search of Memory. Kandel, also a Nobel Prize winner, had met Eccles in the 1960s and learned how badly he had been doing 20 years earlier and what had helped him out of his slump.

The turning point came when Eccles met Karl Popper in 1946. The influential philosopher and science theorist had emigrated to New Zealand shortly before his native Austria was annexed by Nazi Germany. Eccles had also been teaching and researching at the University of Dunedin since 1944, and the two met at the university lecturers' club. The philosopher gave the neurophysiologist a whole new perspective. No one doubted his research results. It was only his interpretations of these results that were controversial. Ultimately, however, the greatest advantage of the scientific method was its ability to refute a hypothesis. On the other hand, it was not possible to confirm a hypothesis definitively. In order to be able to confront conflicting assumptions with each other, the facts must be clear and their conflicting interpretations must be formulated with the utmost precision. Eccles later wrote about Popper: “He even taught me to rejoice in the refutation of a cherished hypothesis, because that too is scientific progress and because much can be learned from refutation.”

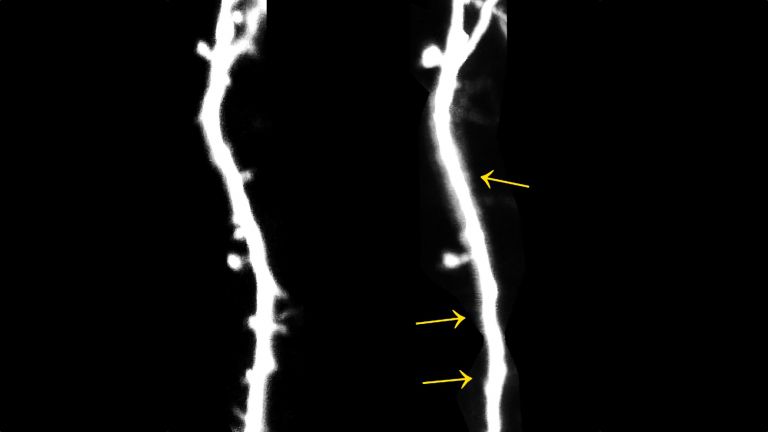

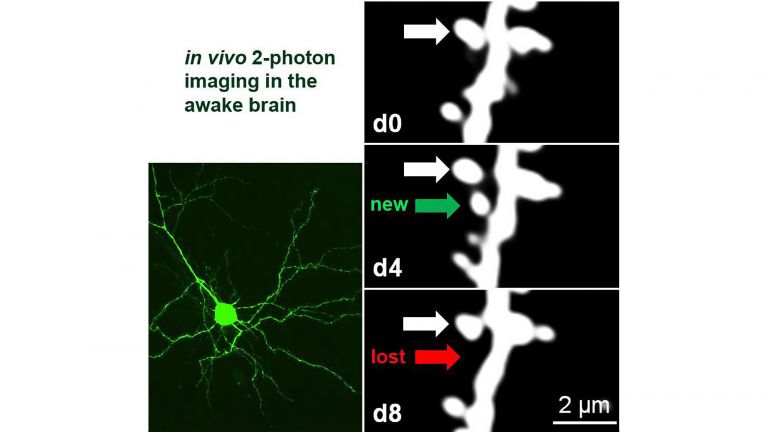

In line with Popper's thinking, Eccles set about clearly formulating his electrical hypothesis and conducting rigorous experiments to test it. August 20, 1951, in the laboratory of the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand, would bring the final decision on whether Eccles' assumption was correct. He and his colleagues set out to measure electrical potential within a cell of the central nervous system for the first time. They insert a newly developed glass microelectrode into a motor nerve cell in the spinal cord of an anesthetized cat.

The researchers are stunned

According to Eccles' now strictly formulated hypothesis, the membrane potential in the nerve cell should actually be positive for a short time. But to the researchers' surprise, it turns out to be negative. “We were briefly stunned,” Eccles later wrote. As they recovered from the shock in the early hours of the morning, the decision was made. Synaptic inhibition is chemically mediated. Eccles converted, and from then on advocated the opposite of his previous theory – just as vehemently.

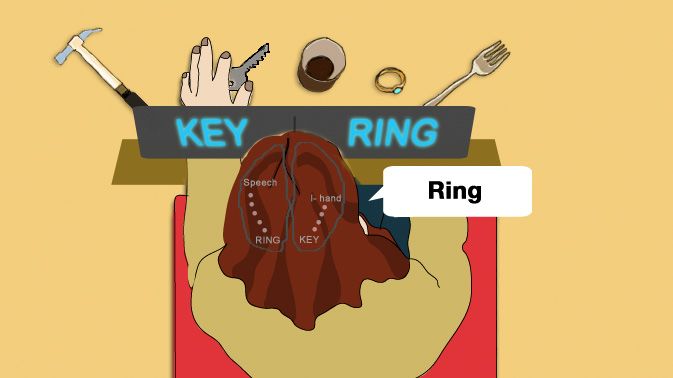

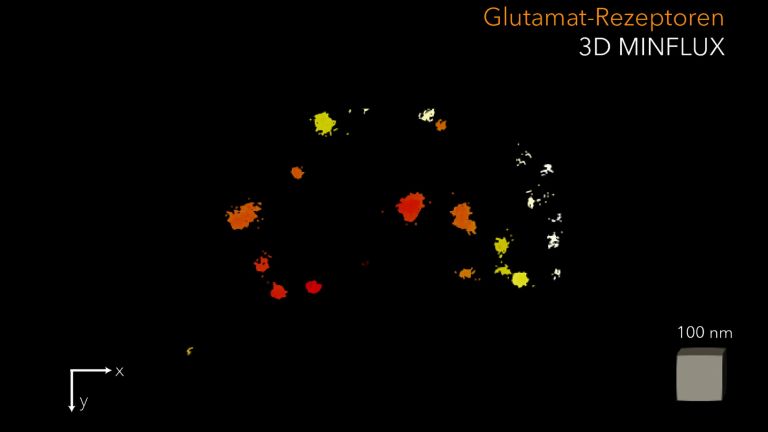

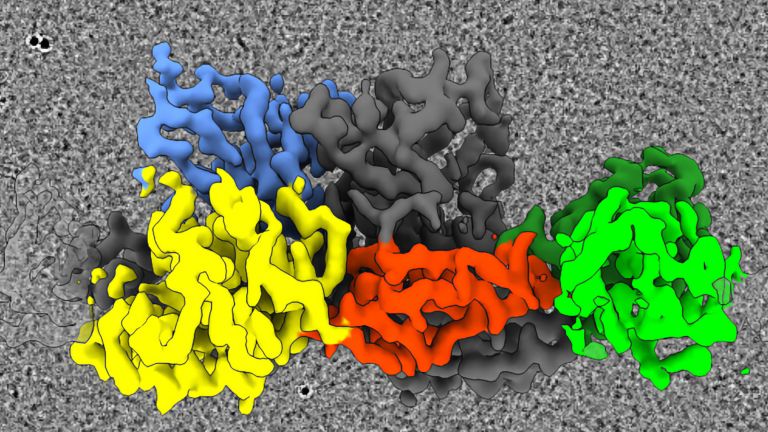

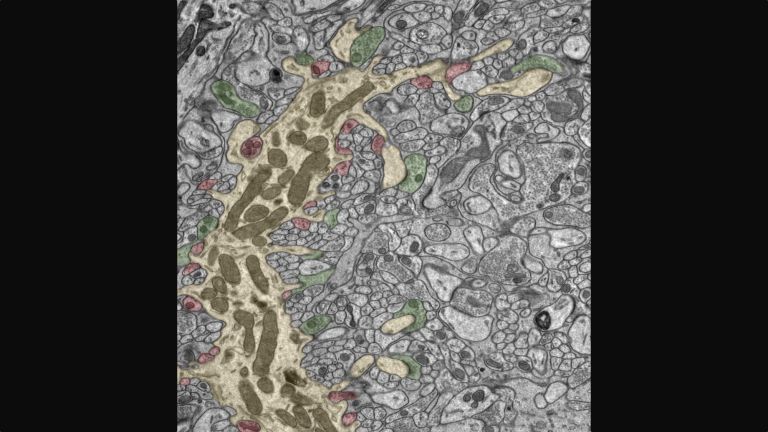

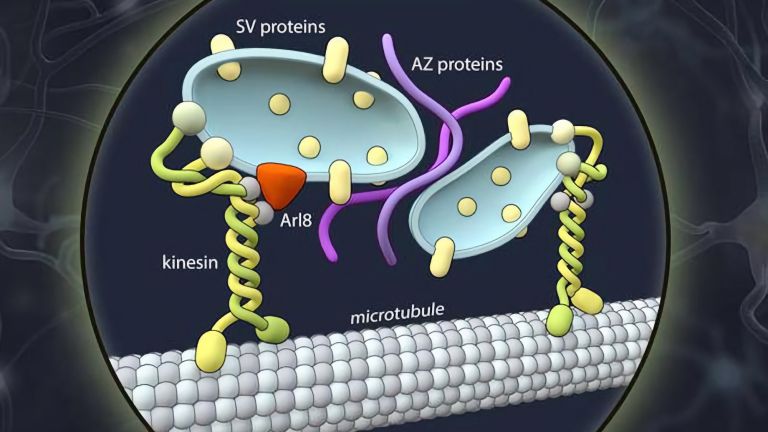

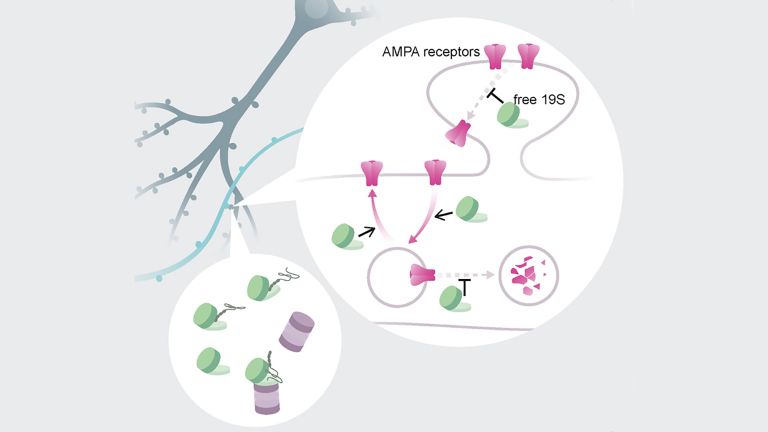

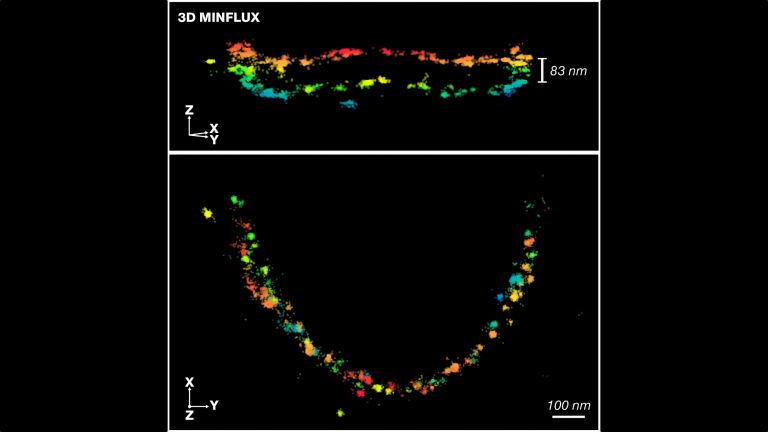

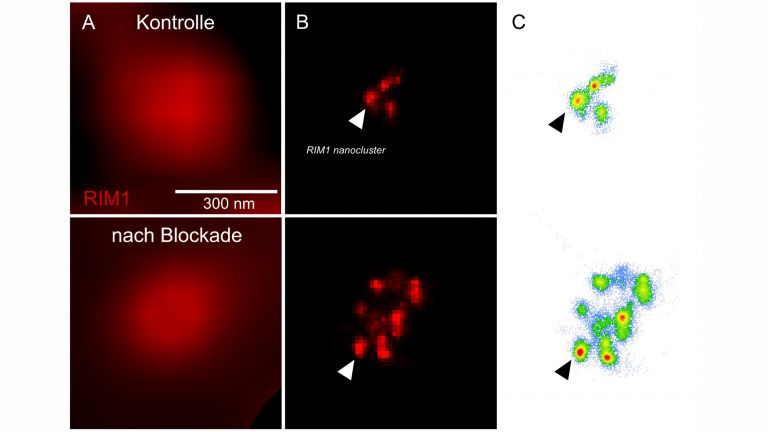

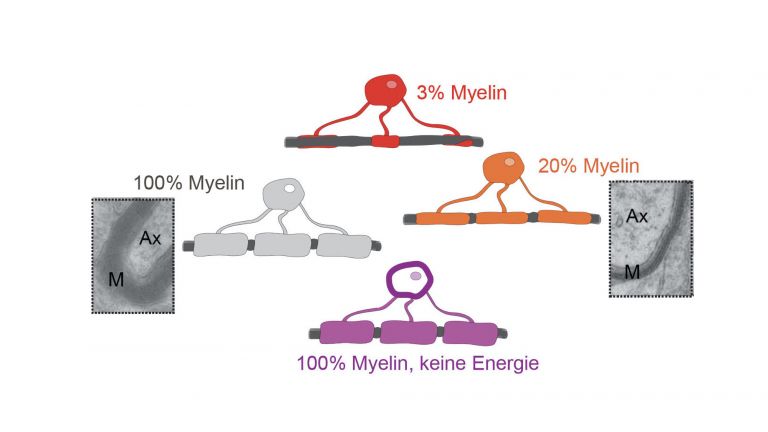

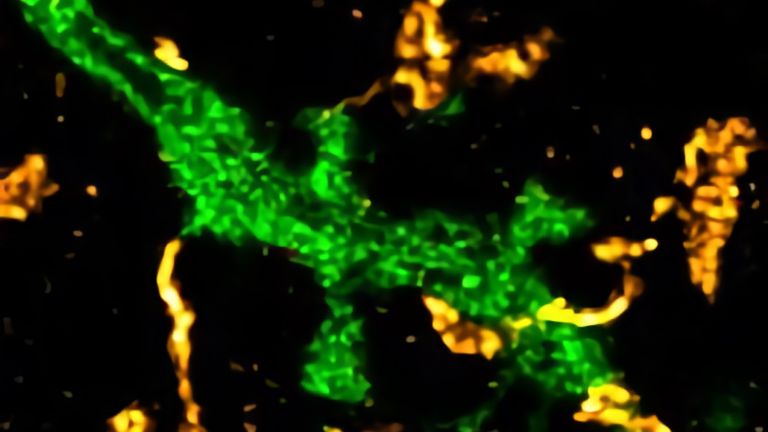

This discovery alone would have made him immortal in the field of neuroscience, but his more than 500 publications contained many other gems. Thanks in part to the research of the Australian neurophysiologist, we now know that when a nerve cell fires, it releases neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine, which enter the synaptic cleft and bind to the receptors of the neighboring cell. This opens channels in the cell membrane, allowing ions to flow into or out of the cell. This also changes the voltage in the downstream cell, thus transmitting the signal.

A single potential at a synapse has little influence on whether an action potential is triggered, i.e., a neuron fires. There are two different types of synapses: excitatory and inhibitory. When an excitatory potential arrives in a cell, the probability of an action potential being triggered increases. Many such impulses can add up and trigger an action potential. An inhibitory potential, on the other hand, reduces the probability that the neuron will fire.

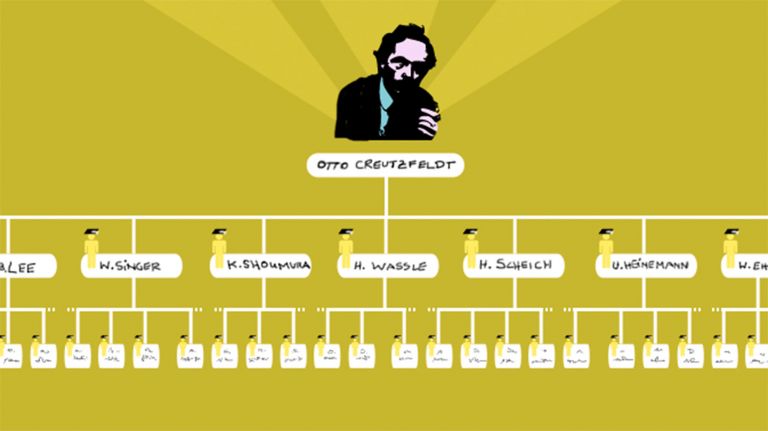

Eccles was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology in 1963 for his discoveries on synaptic transmission. He shared the prize with British physiologists Alan Lloyd Hodgkin and Andrew Fielding Huxley. Fellow researchers attribute his success to Eccles' remarkable talent, motivation, and perseverance. His energy and hunger for new knowledge were overwhelming. As a team leader, he was considered demanding, expecting every member to contribute fully in a collegial manner.

Recommended articles

Formative experiences in his early years

John Carew Eccles was born on January 27, 1903, in Melbourne, the son of a teacher couple. His scientific interest became apparent at an early age. In his book The Self and Its Brain, Eccles recalled how, at the age of 18, he was struck by a feeling of uniqueness. He marveled at his own brain and its ability to produce thoughts and feelings. For Eccles, this experience was the starting point for a lifelong quest to explain these human abilities.

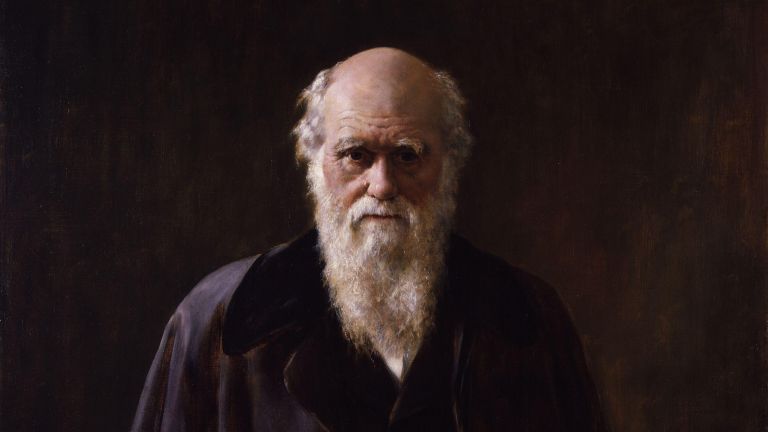

While studying medicine, he began reading fundamental books such as Darwin's On the Origin of Species, and he was also captivated by philosophical works. But even this did not enable him to answer a question that preoccupied him throughout his life: How are the material brain and the spiritual mind connected? He was concerned with the mind-body problem, for which he could find no solution. He also realized how little was known about the brain itself. As a medical student, Eccles therefore decided to become a neuroscientist.

Equally influential was his reading of the book The Integrative Action of the Nervous System by Charles Scott Sherrington, who later won the Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology. Eccles deliberately chose Oxford, where his great role model Sherrington worked, as the starting point for his scientific career. He conducted research there from 1927 to 1931 – at times with Sherrington himself – on signal transmission across the synaptic cleft.

John Eccles as a philosopher

His philosophical and scientific interest in the relationship between the brain and the mind never left him. His problem was that he himself believed in an immaterial mind, in a self that exists independently of the material brain. In scientific circles at that time, as today, the prevailing view was that mental processes were ultimately nothing more than material processes in the brain. Here, too, it was Karl Popper who helped Eccles. Popper taught that the world should be divided into three areas: the physical world, including the brain; the world of consciousness; and the world of cultural objects, such as scientific theories. These three areas are independent of each other, but they can have a causal effect on each other. On this basis, Popper and Eccles developed a variant of so-called interactionist dualism in their book The Self and Its Brain. The immaterial mind should exist independently of the brain, but interact with it.

However, it seemed to contradict the law of conservation of energy if an immaterial mind were to act on physical reality out of nowhere, so to speak. In his latest book, How the Self Controls Its Brain, Eccles attempts to address this problem with the help of quantum physicist Friedrich Beck. Eccles argues that in voluntary actions, for example, so-called psychones, the smallest mental units, increase the probability of individual neurons firing in quantum physics.

To the extent that they engage with it at all, neuroscientists and philosophers today reject Eccles' theory. It is generally regarded as an example of how much the thinking of brain researchers is sometimes influenced by religious beliefs. Indeed, Eccles was a devout and spiritual man who believed in divine providence. Based on his idea of an immaterial spirit, Eccles also hoped for life after death. He died in 1997 – whether his soul lives on in this sense is left to the reader's belief. What is certain, however, is that Eccles has made himself immortal with his scientific achievements.