Aristotle: The Brain as a cooling System

Aristotle believed that the brain was merely a cooling system for the heart. The heart he regarded as the seat of the perceptive soul. Despite these errors, he had a major influence on the history of brain research.

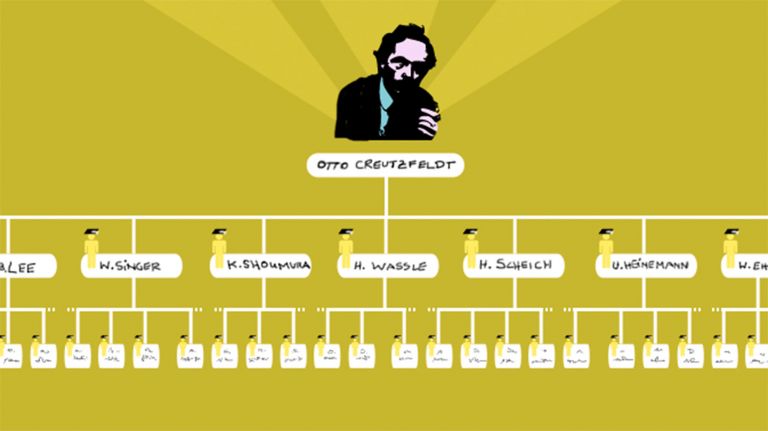

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Georg W. Kreutzberg

Published: 29.01.2014

Difficulty: intermediate

- Aristotle is the great empiricist among the ancient philosophers. Among other things, he dissected sea urchins for his research.

- For Aristotle, the brain is nothing more than a cooling system for the heart. The heart, on the other hand, is the seat of the perceptive soul.

- He was important for brain research in the following centuries due to his strongly biologically oriented interpretation of consciousness. In addition, his teaching on pneuma, a material life force, influenced brain researchers of the next generations.

The brain is nothing more than a cooling system for the blood, while the heart is the seat of the perceptive soul. At least, that was the explanation given by the Greek philosopher Aristotle. But how did he arrive at these assumptions, which seem rather strange from today's perspective? After all, Aristotle was probably the Greek thinker who drew most heavily on experience, accumulating mountains of empirical material in the process.

Aristotle was born in 384 BC in Stageira in the north of what is now Greece. At an early age, he arrived at the Macedonian royal court in Pella, where his father was the king's personal physician. It was here that he received his first education and developed his love of natural science. Later, he went to Athens to complete his education at Plato's philosophical academy. He worked there for twenty years.

Empiricist to the core

Unlike his teacher Plato, who tended toward poetry and bold flights of fancy, Aristotle was more of a sober thinker. With his dry manner, he tended to collect, examine, and catalog almost everything he could get his hands on. Alexander the Great, whom Aristotle taught for a time, is said to have instructed his gardeners, fishermen, and hunters to send him specimens of all the animal and plant species they encountered.

Aristotle was interested in medicine, biology, and physics, among other things. Like any good scientist, he strove for the general and the necessary. But the individual sensory details were always important to him. So how did he arrive at the strange insights about the heart and brain mentioned above?

Recommended articles

The heart as the epitome of life

As in most ancient cultures, such as Egypt or China, the heart was considered the most important organ of thought in ancient Greece. Aristotle himself had also conducted anatomical studies, dissecting a wide variety of dead and living animal bodies, from sea urchins to elephants. He had good reasons for overestimating the heart and underestimating the brain. After all, injury to the heart means immediate death, while brain injuries usually have less dramatic consequences and can even heal. In addition, changes in our heartbeat are accompanied by changes in our state of mind. Conversely, the brain appears to be insensitive, because touching the brain of a living animal does not elicit any reaction from it.

The movements of the heart seem to be synonymous with life itself. For Aristotle, therefore, the heart is the central organ. However, he sees it only as the seat of the perceptive soul. Active reason, the highest function of the soul, on the other hand, does not require a physiological basis for its activity and has no physical location. Aristotle concludes this from the ability of reason to recognize everything, whereas perceptions are bound to the corresponding sensory organs.

The brain as a cooling system

According to Aristotle, the brain merely functions as a cooling system designed to lower the temperature of hot blood. Interestingly, he also refers to the observation that the heart feels warm, but the brain feels cold.

Although Aristotle does not recognize the brain as the central organ of thought and sensation, his biologically inspired theory of the soul has made a significant contribution to the history of brain research. His description of what the English neurophysiologist Charles Scott Sherrington (1857–1952) called the “biological equipment of consciousness” was adopted by brain research and became the paradigm for centuries. Ultimately, the soul – with the exception of active reason – acts together with all its parts and the organs of the body.

Last but not least, Aristotle takes a clear position on the question of whether blood or “pneuma” – an airy form of life energy, comparable to the Chinese chi and the Indian prana – is the material carrier of life force: “All animals naturally have innate pneuma and exercise their power by means of it.” In doing so, he influenced brain research until the 18th century. However, Aristotle does not attempt to locate the “channels” in the body through which the pneuma reaches the limbs, the sensory organs, and the heart. This was only addressed by subsequent generations, who eventually discovered the nerves.