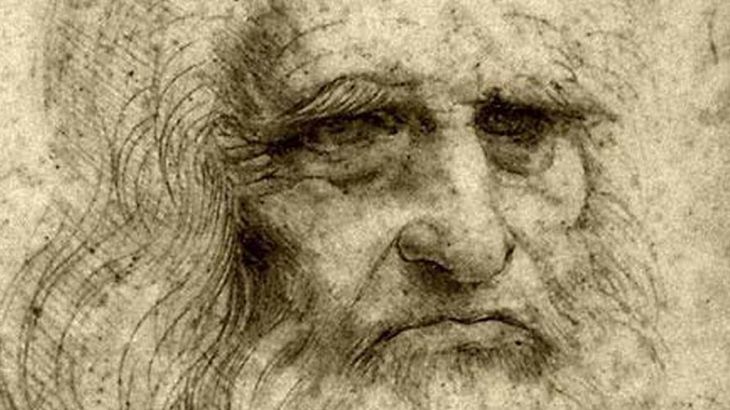

Leonardo da Vinci: Artist and Scientist

Leonardo da Vinci produced scientific illustrations of the brain during the Renaissance. He was certain that science needed painting and painting needed science.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Ortrun Riha

Published: 19.05.2016

Difficulty: intermediate

- For Leonardo da Vinci, painting and science were not separate spheres: painting needed science to understand what it was depicting, and science needed painting to present its findings.

- Leonardo studied the human body not only to be able to paint it better, but also to understand it better.

- He was very interested in the sense of sight and the ventricles of the brain. This is because tradition located cognitive abilities and the seat of the soul in these areas.

- By pouring wax into the ventricles of the brain, Leonardo was the first to recognize their true appearance.

- Because he did not publish his findings during his lifetime, they had little influence on the history of brain research.

“The painter who merely depicts is like a mirror that imitates things without knowing them”: for Leonardo da Vinci, art and science were not separate spheres. A good painter must know the sciences – mathematics, optics and, above all, anatomy, all the tendons, bones, muscles and fibers, the tiniest veins. And science needs painting, because it captures and presents the essence of natural phenomena and summarizes in a single image what researchers have studied in many examples in nature and cannot express in words. Ultimately, painting itself is a science. With this conviction, Leonardo da Vinci painted, researched, and invented his way through the world of the Renaissance. This conviction, write Daniel Cavalcanti and colleagues of the Instituto Estadual do Cérebro Paulo Niemeyer in Rio de Janeiro, was also the beginning of the scientific representation of the brain.

Born on April 15, 1452, at three o'clock in the morning in Vinci, Tuscany, the son of a notary and a farmer's daughter received his training in the workshop of the Florentine sculptor, goldsmith, and painter Andrea del Verrocchio. In 1482, he entered the service of the Duke of Milan, Lodovico Sforza, for whom he designed fortifications and war machines in addition to his artistic work. After Milan was conquered by the French in 1499, Leonardo first fled to Venice, later returning to Florence. In 1502, he entered the service of Cesare Borgia. Until 1516, he lived alternately in Rome, Milan, and Florence, then moved to Amboise on the Loire in France at the invitation of the French king, Francis I. He planned canals and designed bridges for him. He died near Amboise on May 2, 1519. His tomb was destroyed in the turmoil of the European wars of religion.

The jack of all trades

Leonardo da Vinci was not only a painter and anatomist. He was also a sculptor and architect, mechanic, engineer, and natural philosopher. He created the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper, designed flying machines, water pumps, swing bridges, and a car. He drew maps and theater sets, studied clocks and the movement of the planets, and examined ancient vases. There was hardly any field that Leonardo was not interested in. He was also well-read: “We know of more than 150 books that Leonardo owned and read, including a lot of medieval psychology,” explains Jonathan Pevsner, a brain researcher at the Kennedy Krieger Institute at the University of Baltimore. He studies the genetic basis of childhood brain disorders – and Leonardo: “When I was 17, I saw a drawing by Leonardo in a museum in London and sat in front of it for hours. He has fascinated me ever since.”

Anatomical studies were part of the training of painters in Leonardo's time. But Leonardo's interest went far beyond that. He didn't just want to paint the human body, he wanted to understand how it worked. He was particularly interested in the heart and the brain. The heart because it maintains blood circulation, the brain because, like most researchers and scholars of his time, he wanted to know how the soul and the body are connected. The most important principle of his research was to trust only mathematics and his five senses, especially what he saw.

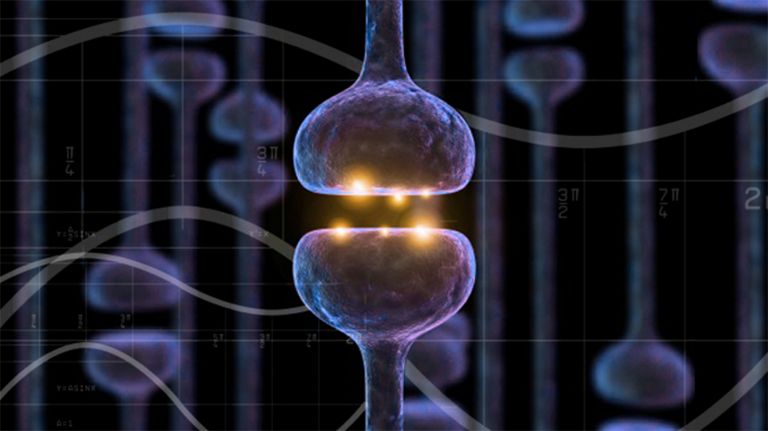

The ventricles: in search of the soul

His first drawings of the human skull date back to 1489, including a cross-section that is considered the first to show the large veins anatomically correctly. Like his predecessors since ancient times, he was particularly interested in the fluid-filled cavities of the brain, the ventricles. “When you look at the brain, you see a soft and somewhat disgusting mass. It was probably difficult to imagine that this had anything to do with the mind and cognitive abilities,” says Pevsner: “That's why people thought that if the soul was located in the brain, then it must be in the ventricles.”

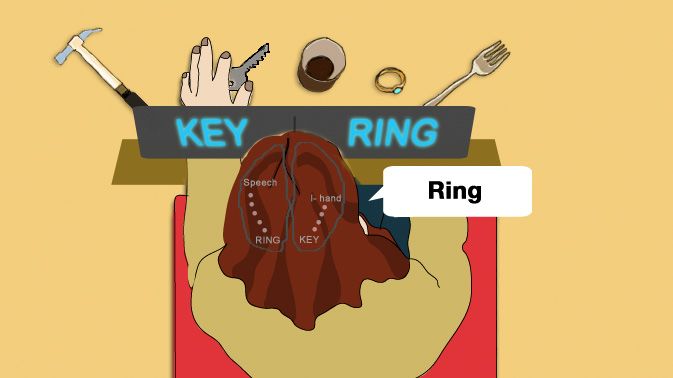

In an early drawing by Leonardo, the three ventricles are traditionally arranged in the middle of the brain like lemons on a fruit skewer. Scholars at the time located Memory in the rear ventricle, thinking in the middle ventricle, and the bundling of sensory impressions, the sensus communis, in the front ventricle. Then Leonardo conducted an experiment: he took the brain of an ox and filled the ventricles with wax. When the wax had hardened, he removed the remaining parts of the brain. What remained was an impression of the ventricles that bore no resemblance to a string of lemons. Based on this specimen, Leonardo was able to produce the first realistic drawing of the Ventricular system Pevsner repeated the experiment with a sheep's brain, wax from a beekeeper, and the help of a neurosurgeon, and has admired Leonardo even more ever since: "He knew nothing about fixing brain tissue, nothing about the openings of the ventricles, and yet he managed it. He used his knowledge of models and impressions, which he had acquired as an artist. That was very original."

Leonardo did not abandon his ventricle theory, but he modified it on the basis of his anatomical studies and the special importance he attached to vision. He was also the first to discover that the optic nerves travel from the eyes to the opposite Hemisphere of the brain. Leonardo now reserved the foremost structure of the ventricular system, i.e., the one closest to the eyes, for receiving stimuli from the Optic nerve From there, visual information would be transferred to the central ventricle and combined with information from the other senses. Leonardo considered the Eye to be the most important sensory organ, coordinating and controlling all other impressions. Also noteworthy is the precise depiction of the course of the cranial nerves at the base of the skull.

Memory

Memory is a generic term for all types of information storage in the organism. In addition to pure retention, this also includes the absorption of information, its organization, and retrieval.

Ventricular system

A system of cavities in the brain filled with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). This provides protection, nutrition, homeostasis, and waste removal for the brain.

Hemisphere

The cerebrum and cerebellum each consist of two halves – the right and left hemispheres. In the cerebrum, they are connected by three pathways (commissures). The largest commissure is the corpus callosum.

Optic nerve

nervus opticus

The axons (long fiber-like extensions) of the retinal ganglion cells form the optic nerve, which leaves the eye at the back of the optic disc. It comprises approximately one million axons and has a diameter of approximately seven millimeters.

Eye

bulbus oculi

The eye is the sensory organ responsible for perceiving light stimuli – electromagnetic radiation within a specific frequency range. The light visible to humans lies in the range between 380 and 780 nanometers.

cranial

A positional term – cranial means "towards the head." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction along the neural axis, i.e., forward.

In animals (without upright gait), the designation is simpler, as it always means forward. Due to the upright gait of humans, the brain bends in relation to the spinal cord, where cranial also means "upward."

Recommended articles

A somewhat chaotic genius

As spectacular as Leonardo's discoveries in the field of brain anatomy were, they had little influence on the history of brain research, as most of them were not published until the end of the 19th century. Over the course of his life, Leonardo is said to have filled more than 20,000 pages with drawings and texts, about a third of which have been preserved. A glance at these sheets gives an impression of the precision of his drawing skills, his curiosity, and his energy. At the same time, they appear exuberant and chaotic, with drawings of very different things squeezed onto one page, the text winding its way between them. Leonardo's notes can only be read after some practice, as he wrote in mirror writing. “Some people wanted to see a secret code in it, but I think Leonardo was left-handed and when he was pressured to write with his right hand, he turned the letters around, which is often seen in left-handed people,” says Pevsner. Leonardo was perfectly capable of writing the right way up; sometimes he wrote the first column in one direction and the next in the other.

Not only his papers, but his entire working method tended to be poorly organized. He started many projects that he never finished, always pursuing several leads at once and always moving on to the next discovery, the next work of art. He never brought his many theories together into a consistent body of thought. Even a planned anatomical atlas never came to fruition because a friend and colleague with whom he wanted to undertake the project died of the plague. As a result, science historians today can only find traces here and there of the influence Leonardo's work had on other artists who saw his works.

And a likeable person

“He just liked to experiment and have fun,” says Pevsner. “We know from contemporary reports that he impressed everyone he met, that he was charming and funny, that he told jokes and performed tricks at the royal court, and that he had many friends.”

For Pevsner, there are two things in particular that we can still learn from Leonardo today: to be creative in research and to look closely. “Above all, Leonardo was able to see,” says the brain researcher. "The problem today is exactly the same as it was in the past: we only see what we expect to see. Leonardo, on the other hand, was very open-minded. He wanted to see, and he saw much more than his contemporaries. In this respect, he can still be a role model today."

Further reading

- Jonathan Pevsner: Leonardo da Vinci’s contributions to neuroscioence. Trends in neurosciences, 2002, Vol. 25, No 4. (abstract)

- Daniel D. Cavalcanti, et al Anatomy, technology, art, and culture: toward a realistic perspective of the brain, Neurosurgical Focus, 2009, Vol. 27, No. 3 (text)

- Da Vinci and the Brain (webseite )