Minds and Ideas

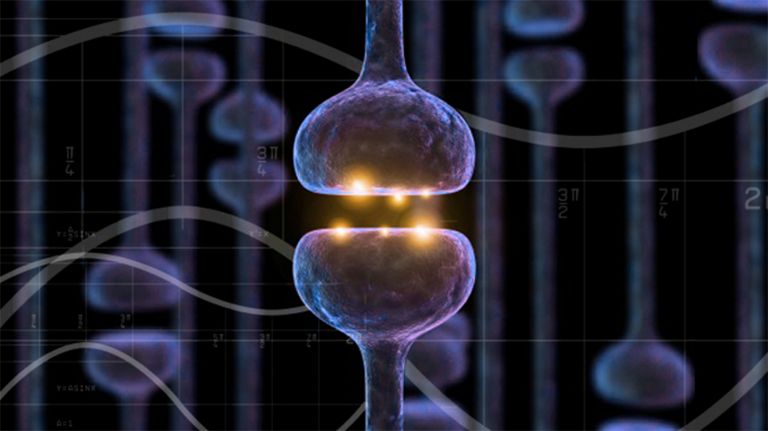

Die Erforschung des Gehirns speist einen steten Fluss an Information, der irgendwann in Lehrbüchern mündet. Doch hinter der manchmal trockenen Theorie vergessen wir oft die Menschen hinter der Entdeckung.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Herbert Schwegler

Published: 26.09.2012

Difficulty: intermediate

What is written in neuroscience textbooks today is often detailed and complex – and therefore rarely easy to understand. What it means to be human disappears behind the manifold connections, as do the researchers to whom we owe them. Only very few have been immortalized in anatomical structures, and even here we forget that these names once belonged to people and that the cranial nerve nucleus was not always called that. But in fact, Edinger and Westphal were real people, just like Broca and Wernicke.

People and stories

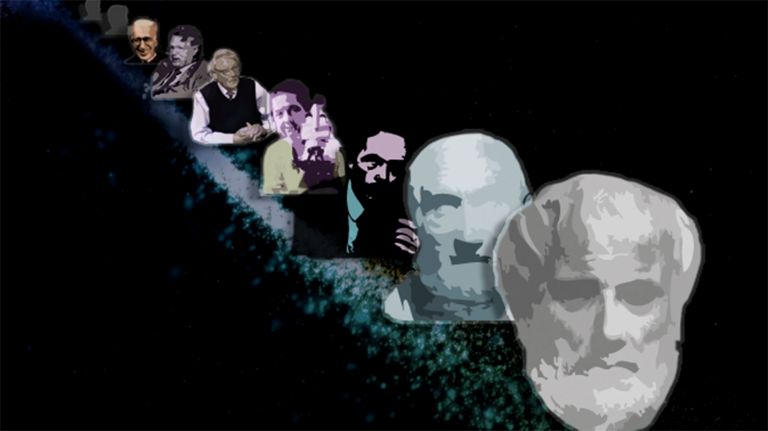

As a look at our own biographies shows us, life is not always easy. People have big emotions and do stupid things. They get bogged down in theoretical dead ends or are the only ones who see a way out. They are stubborn, determined, desperate, brilliant – not necessarily all at the same time. Their biographies take leaps and bounds, contain darker and lighter chapters. And some really good stories.

That's what the topic of milestones is all about – important discoveries in neuroscience and the people who made them. Their idiosyncrasies, their experiences, their view of things. Researchers and research become intertwined – when ▸ Rita Levi-Montalcini, a Jew persecuted by Italian fascists, sets up a makeshift laboratory in her bedroom and works “under conditions like Robinson Crusoe,” it says something about scientific curiosity. When ▸ Camillo Golgi, in his speech on the occasion of his joint Nobel Prize with Ramón y Cajal, “critically examines” his Nobel colleague, it says something about conviction in one's own idea. And when ▸ Roger Sperry, together with his students Michael Gazzaniga and Joseph LeDoux, both of whom are now also very prominent neuroscientists, suddenly encounters a possible second consciousness in split-brain patients, while the first proves to be a very convinced but hapless interpreter of supposed facts, then that says something about us. Very directly and personally.

Recommended articles

Incomparable spectrum

Rita Levi-Montalchini's growth factors and Roger Sperry's hemispheric research are several orders of magnitude apart, yet together they define us. It is not without reason that Eric Kandel once said that only brain researchers can explore the entire vast field from genes to the psyche.

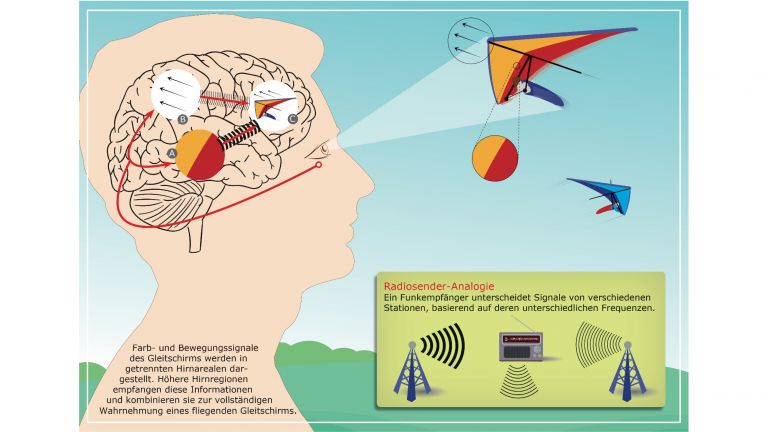

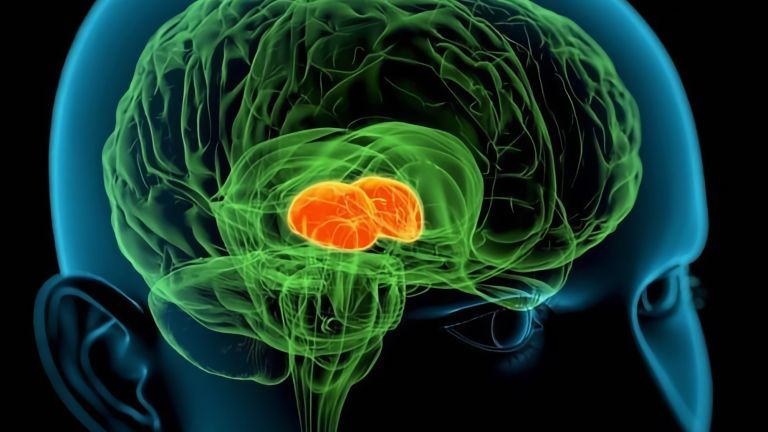

And that is what brain researchers have been doing since ancient Greece, with varying levels of knowledge, different methods, and different results, depending on their position on the timeline. In ancient Greece, ▸ Aristoteles still believed that the brain was little more than a cooling system for the blood. ▸ Alkmaion of Croton, on the other hand, 300 years earlier, already saw the brain in much the same way as we do today: “It is the brain that allows the perceptions of hearing, seeing, and smelling; from this arise memory and imagination, but from memory and imagination, once they have settled and come to rest, knowledge is formed” (quoted from Oeser, 2002).

To put this into context

Today, it is easy to smile at Aristotle's misjudgment, but researchers are not only intellectual children of their time, they are also limited to the content of the scientific toolbox available at that time. This even included bullets – they caused well-defined damage to the brain, which was finally examined by well-trained doctors from World War I on. This led to a reasonably reliable correlation between damaged tissue and impaired function. On the other hand: ▸ Galen drew similar conclusions 1,800 years before that. However, he did so on gladiators.

Today, things look very different – basic research methods ranging from genome sequencing to big data to 2-photon microscopy allow researchers to examine a question from many angles. As a result, the lists of authors in publications are getting longer and longer.

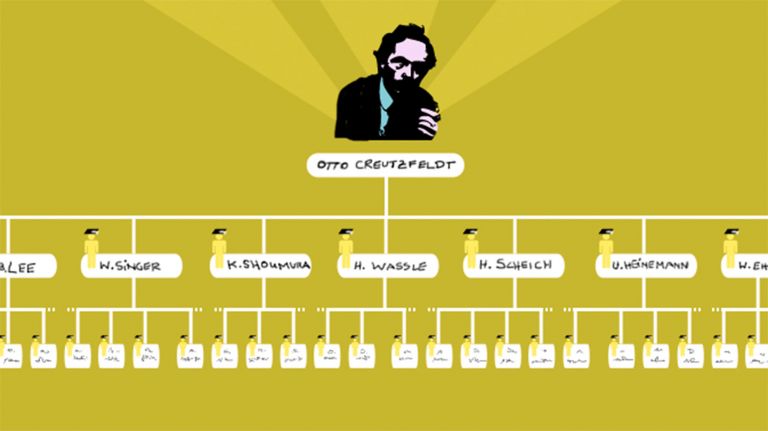

When it comes to this topic, we look not only at fame, but also at significance. While, for example, ▸ David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel are mentioned in every textbook for their findings on the organization of the cerebral cortex, ▸ Otto D. Creutzfeld is better known among experts. His students include some of the most famous German neuroscientists. We also want to focus on younger researchers, so over time we will present a balanced spectrum of minds and ideas.

And tomorrow?

This raises the interesting question of what brain research will look like in 20, 50, or 100 years. Will researchers then smile at today's findings as well? And what will they compare the brain to? After all, over the centuries, we have always compared this organ between our ears to the most complex system known at the time – hydraulics, computers, and today, complex systems. We can look forward to finding out ...