John O’Keefe and the Moser Couple: Place Cells

How do we actually find our way from one point to another? John O'Keefe,May-Britt Moser, and Edvard Moser set out to find the answer in the brain. Their discoveries – place cells and grid cells – earned them the Nobel Prize in 2014.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Denise Manahan-Vaughan

Published: 31.10.2014

Difficulty: intermediate

- In 1971, John O'Keefe discovered so-called place cells in the brains of rats. These cells fired whenever the rodents were in a specific location. The cells apparently signal the location where one is.

- The firing of several place cells together creates a kind of mental map of the environment.

- In 2005, Norwegian researchers May-Britt Moser and Edvard Moser discovered other orientation cells, known as grid cells. The activity of these cells enables the creation of a kind of coordinate system that represents the distance between different locations.

- In 2014, John O'Keefe,May-Britt Moser, and Edvard Moser were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discoveries.

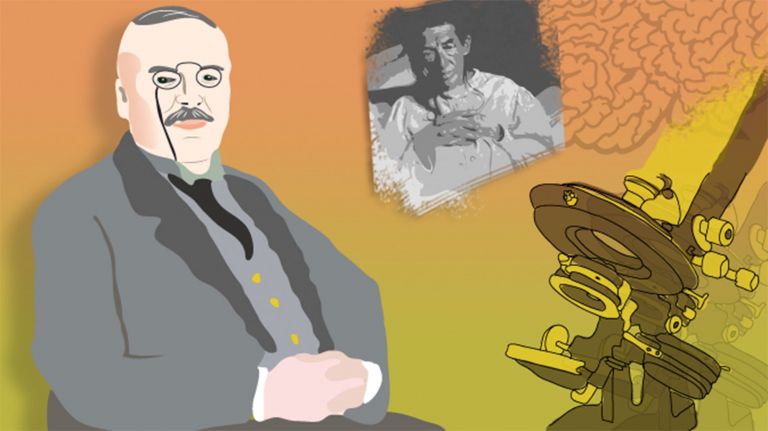

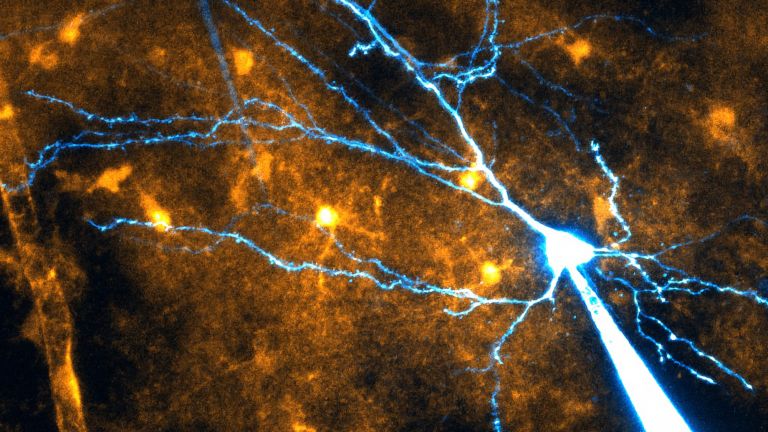

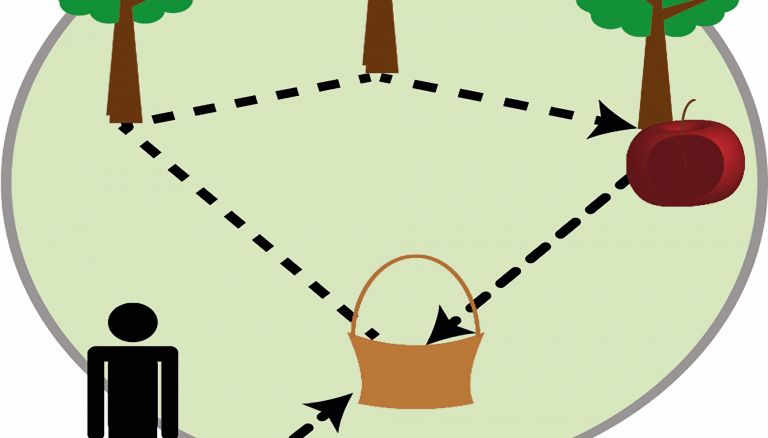

In 1971, John O'Keefe took a slightly different path. And with him, his laboratory animals. At that time, researchers usually subjected their animal test subjects to a strict experimental protocol. For example, they presented the animals with stimuli and recorded how the rodents' brains reacted to them. Not so O'Keefe. He let his rats roam freely in a laboratory enclosure. Not for fun, but to find out how the animals' brains contribute to orientation. This was made possible by a technology that was still relatively new at the time: microelectrodes implanted in the brain. The neuroscientist used these to record the activity of individual nerve cells while the rats explored the area.

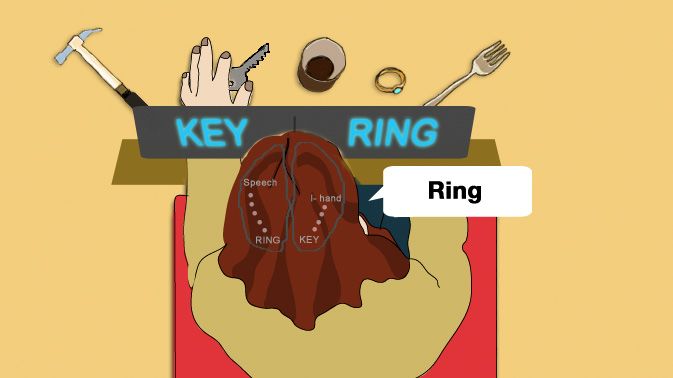

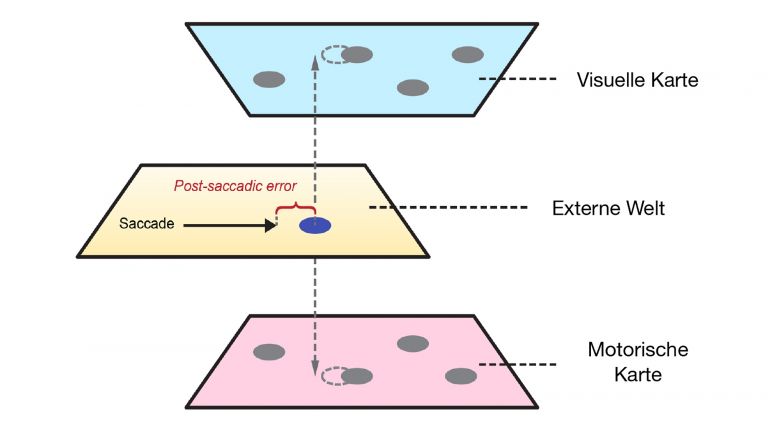

The results were surprising even to John O'Keefe: individual nerve cells in the hippocampus were extremely selective about when they fired. They became increasingly active whenever the small rodents were at a certain point in the cage. If they were in a different place in the enclosure, a different cell fired. Even when O'Keefe turned off the lights in the laboratory, the neurons continued to be active in this characteristic way. The nerve cells did not simply register visual input. Apparently, special neurons served as a kind of landmark: they signaled where the rats were in relation to certain features in the room. The activity of the individual nerve cells represented different context-dependent points in an environment, and the combination of their individual activities resulted in a kind of experience-dependent mental map of this area. At least, that was O'Keefe's assumption. He then referred to the special nerve cells as place cells and formulated the theory of cognitive maps in the brain, which remains influential to this day. Further experiments by the neuroscientist suggested that the individual place cells also represent the cellular basis of spatial memories. The memory of a particular environment is stored as a specific combination of place cell activity in the hippocampus.

John O'Keefe was born on November 18, 1939, in New York City to Irish immigrants. After studying at the City College of New York, he received his doctorate in physiological psychology from McGill University in Canada in 1967. He then went to University College London in England, where he began his groundbreaking research. He was fascinated by the problem of how the brain controls behavior. However, he was also open to the philosophical aspects of neuroscientific findings. Referring to a theory by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), the researcher once said: “I believe that our sense of objective three-dimensional space comes from the brain and not from the physical world.”

Intensive years of learning

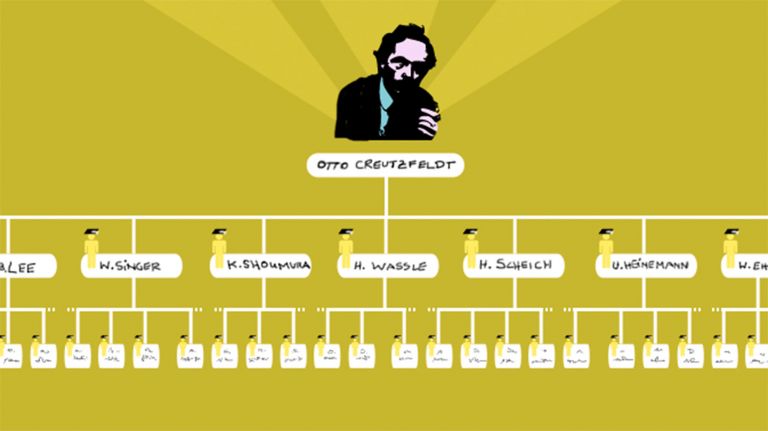

John O'Keefe worked with many colleagues during his research career. However, one particularly influential encounter was with the research couple May-Britt (born January 4, 1963) and Edvard Moser (born April 27, 1962). The two Norwegians had met at the University of Oslo in the early 1980s. With their wide range of interests, they studied mathematics, psychology, and statistics, among other subjects. Their particular scientific passion was spatial memory and spatial orientation. From then on, the two worked and lived together. After both had earned their doctorates, they spent several months with John O'Keefe in his laboratory at University College London. He taught them how to record the activity of place cells in the hippocampus. The couple later recalled that this was possibly the most intense learning experience of their lives.

Shortly afterwards, the Mosers were able to apply their newly acquired knowledge in their own laboratory. They built it practically from scratch in a basement at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim. In the beginning, they had to do a lot of things themselves and were not above cleaning the cages of the experimental rats by hand.

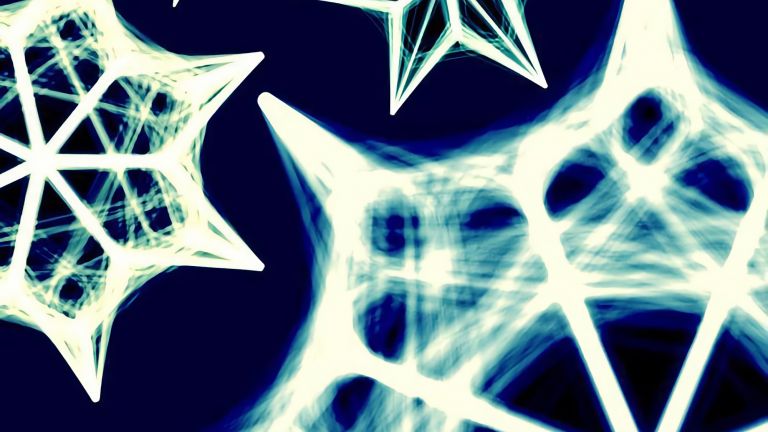

Strange pattern

In their own laboratory, May-Britt and Edvard Moser wanted to find out whether the signals from O'Keefe's place cells actually came from the hippocampus or from elsewhere in the brain. They suspected one location in the brain, the entorhinal cortex, which lies above the hippocampus. So, they let their test animals run around freely in a larger enclosure than usual and recorded how the nerve cells in the region of the entorhinal cortex behaved. In doing so, they encountered a strange pattern of activity in the nerve cells. For a long time, the Mosers did not know what they were dealing with: the fireworks of cells in the entorhinal cortex resembled the signals of the place cells in the hippocampus, with one significant difference. This time, the special neurons were not only active when the animal was in a specific location. One and the same nerve cell was stimulated at several, but equally specific, locations. When the Mosers connected these locations in the enclosure, a hexagonal pattern emerged, similar to a honeycomb.

Recommended articles

Mental coordinate system

May-Britt and Edvard Moser suspected that these “firing locations” of the cells in the entorhinal cortex divided the animals' environment into a kind of mental coordinate system made up of hexagons. When an animal reached a node in this grid, the corresponding cell fired. This might serve as a measure of distance in the mental maps. The research couple called these cells grid cells. While place cells signal where you are, grid cells apparently provide a sense of distance.

Grid cells in different parts of the entorhinal cortex cover different distances. Sometimes the “firing locations” of the grid are only a few centimeters apart, sometimes they are meters apart. In this way, environments of different sizes can obviously be “measured”.

Another finding by the Mosers: the grid cells are supported by other cells in the entorhinal cortex. For example, “head direction cells” serve as a kind of compass. They cause the mental maps to rotate, so to speak, when the head moves in a certain direction.

Last but not least, the Mosers also found a possible answer to the question that had originally driven their search: Where do the signals from the place cells actually come from? Since the grid cells in the entorhinal cortex transmitted information to the place cells in the hippocampus, the answer was clear to the Mosers: The actual orientation center was the entorhinal cortex, which supplied the hippocampus with the location signals.

Nobel Prize in Medicine for the “navigation system” in the brain

The GPS system in the brain: this is how place cells and grid cells are also referred to – and they have been awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. On October 6, 2014, the Nobel Prize Committee announced that John O'Keefe would receivehalf and May-Britt Moser and Edvard Moser would each receive a quarter of the prize “for their discovery of cells that form a positioning system.” The members of the Nobel Prize Committee spoke of a paradigm shift in our understanding of how ensembles of specialized cells work together to perform higher cognitive functions.

A whole series of questions regarding the orientation cells in the brain remain unanswered. “To this day, we don't know exactly what animals use their grid cells for,” says neuroscientist Michael Brecht from the Bernstein Center for Computational Neuroscience in Berlin to dasGehirn.info. Even though he also suspects that they help to measure space. “It is also unclear exactly how animals generate the grid pattern in the first place.”

It is also unclear to what extent the results from animal studies apply to humans, though studies in recent years have found neurons in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex of humans that appear to be similar to place cells and grid cells.

Perhaps the newly minted Nobel Prize winners will contribute a few more pieces to the puzzle: After all, John O'Keefe is in his mid-80s and still working in the laboratory. He is considered a passionate researcher. And the Mosers, both in their early 60s, are not thinking of retiring anytime soon.

Further Reading

-

Official homepage for the 2014 Nobel Prize in Medicine with comments from the laureates [as of October 29, 2013]: to the website.

-

O’Keefe J, Dostrovsky J.: The hippocampus as a spatial map. Preliminary evidence from unit activity in the freely-moving rat. Brain res. 1971 Nov; 34(1): 171 – 175 (zum Abstract).

-

Hafting T et al: Microstructure of a spatial map in the entorhinal cortex. Nature. 2005 Aug 11; 436(7052): 801 – 806 (zum Abstract).

- Jacobs J et al.: Direct recordings of grid-like neuronal activity in human spatial navigation. Nat Neurosci. 2013 Sep; 16(9): 1188 – 1190 (zum Abstract).