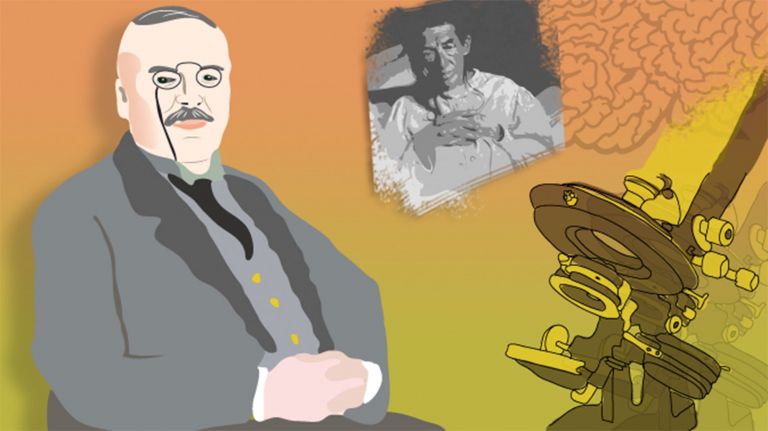

Galen: The Brain as the Central Organ

In the ancient debate over whether the heart or the brain was the central organ, the Greek anatomist Galen took a clear position: it was the brain! Furthermore, his ventricle theory shaped the views of the following centuries.

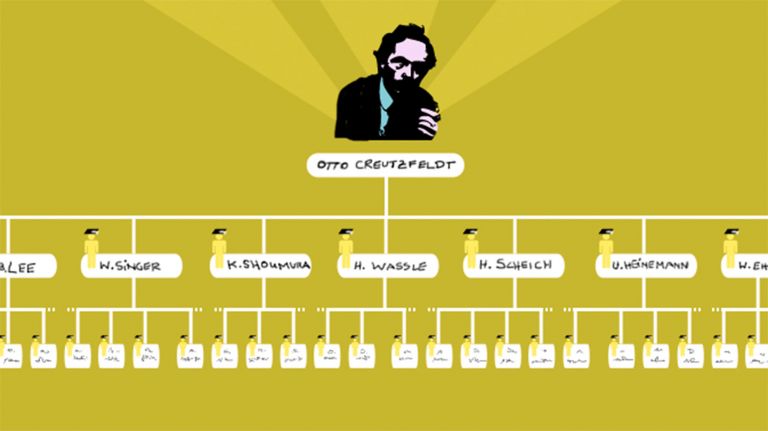

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Georg W. Kreutzberg

Published: 29.01.2014

Difficulty: easy

- The Greek anatomist Galen came into contact with a variety of medical theories during his travels.

- His work as a gladiator doctor provided him with a wealth of illustrative material for his anatomical research.

- He ended the ancient controversy over whether the heart or the brain was the seat of thought and feeling.

- Galen believed that the cavities of the brain, which he thought contained pneuma, were the point of connection between the body and the soul. This (incorrect) theory influenced brain research in the centuries that followed.

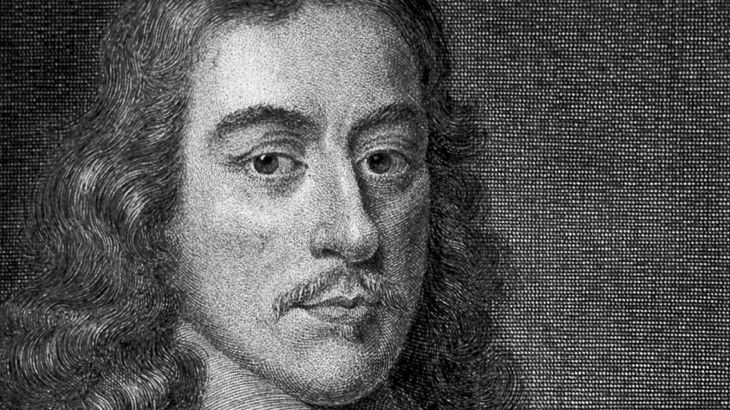

For a long time in ancient times, there was a bitter dispute among researchers: Is the heart or the brain decisive for thinking and feeling? The Greek anatomist Claudius Galenus, also known as Galen, put an end to the controversy several centuries later. He considered absurd the philosopher ▸ Aristotle's idea that the brain was ultimately just a cooling system for the heart. If that were the case, Galen argued, the brain would not be located so far away from the heart.

He also found the claim that the eyes and ears are not connected to the brain unconvincing. After all, he was already familiar with the sensory nerves and, like Herophil and Erasistratos before him, distinguished them from the motor nerves. Galen also made a crucial observation: people can lose their ability to perceive after a stroke even if the sensory organs in question are still functioning. For Galen, this was compelling evidence that the brain plays an important role in perception.

Galen was born around 129, presumably in the ancient Greek city of Pergamon, now known as Bergama in Turkey. His father, an architect and mathematician, taught him philosophy, mathematics, and natural science, thus setting the course for his son's successful career as a philosopher and physician. After his father's death, Galen undertook extensive travels, including to Alexandria, Egypt, the center of medicine at that time. In this way, he came into contact with a variety of medical theories. He himself specialized in anatomical studies.

stroke

Cerebral apoplexy

In a stroke, the brain or parts of it are no longer supplied with sufficient blood, which impairs the supply of oxygen and glucose. The most common cause is a blockage in an artery (ischemic stroke), less commonly a hemorrhage (hemorrhagic stroke). Typical symptoms include sudden visual disturbances, dizziness, paralysis, speech or sensory disturbances. Long-term consequences can include various sensory, motor, and cognitive impairments.

Perception

The term describes the complex process of gathering and processing information from stimuli in the environment and from the internal states of a living being. The brain combines the information, which is perceived partly consciously and partly unconsciously, into a subjectively meaningful overall impression. If the data it receives from the sensory organs is insufficient for this, it supplements it with empirical values. This can lead to misinterpretations and explains why we succumb to optical illusions or fall for magic tricks.

Wounded gladiators as illustrative material

He benefited from his temporary work as a gladiator doctor in Pergamon. This allowed him to gain extensive experience. Galen himself later claimed to have gotten the job by disemboweling a monkey and challenging his medical competitors to repair the damage. When they refused, he took on the task himself and was awarded the position.

War and gladiatorial combat, he wrote, were the greatest school of surgery. They provided him with a steady stream of clinical cases, as the different types of trauma allowed him to draw certain conclusions: a deep wound to the back of the head could lead to blindness. In split skulls, he encountered rhythmic movements of the brain. And by a process of elimination, he was able to determine that cerebral fluid was not identical to the life force: he could see it flowing out, but his patient continued to live. Galen also dissected monkeys, sheep, pigs, and goats, some of them while they were still alive. These dissections reached a new peak with him – in terms of sheer number, but also in terms of cruelty. He performed dissections on animals that were still alive, removing the brain layer by layer to find out what functions the respective organs had.

This obviously did not leave him completely cold. At least, that is what his recommendation to perform dissections on living animals (vivisections) on pigs and goats rather than monkeys suggests, because “in this way you can avoid seeing the unpleasant expression on the monkey's face when it is vivisected.” However, once vivisection had begun, an anatomist should proceed as with a dead animal and penetrate the deep tissues without compassion. He justified the cruelty with a philosophical attitude popular in his time, according to which animals had no rational soul and therefore no personality and no rights.

Recommended articles

Overestimated cavities

During his dissections, Galen was the first to discover that a horizontal cut of the Spinal cord caused paraplegia, but a vertical cut did not. Other conclusions were less significant from a medical point of view. For example, he observed that a cut in the brain of animals only deprived them of their ability to move and feel if it penetrated to one of the brain ventricles. Galen was particularly fascinated by these cavities in the brain, which were filled with cerebral fluid. He himself believed that they contained something similar to air. When Galen pressed on the posterior ventricle of the exposed brain of a living animal, it fell into a state of rigidity. When he made only a slight incision in the roof of the ventricle, the animal blinked its eyes.

Galen therefore assumed that brain injuries only impaired Perception or motor skills if the ventricles were affected. He believed that the cavities of the brain tissue must have a special connection to the soul. Their air-like content, with its insubstantial nature, resembled the soul more than the brain tissue. Galen's description of the contents of the ventricles is reminiscent of the pneuma or spiritus animalis, which, according to ancient philosophy, mediates between the soul and the body. Even though he overestimated the importance of the ventricles and the doctrine of pneuma lost its significance in modern times, Galen's ideas were considered irrefutable doctrine for many centuries and had a lasting influence on brain research.

Spinal cord

medulla spinalis

The spinal cord is the part of the central nervous system located in the spine. It contains both the white matter of the nerve fibers and the gray matter of the cell nuclei. Simple reflexes such as the knee-jerk reflex are already processed here, as sensory and motor neurons are directly connected. The spinal cord is divided into the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral spinal cord.

posterior

A positional term – posterior means "towards the back, located at the rear." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction towards the tail.

Perception

The term describes the complex process of gathering and processing information from stimuli in the environment and from the internal states of a living being. The brain combines the information, which is perceived partly consciously and partly unconsciously, into a subjectively meaningful overall impression. If the data it receives from the sensory organs is insufficient for this, it supplements it with empirical values. This can lead to misinterpretations and explains why we succumb to optical illusions or fall for magic tricks.