Rita Levi-Montalcini: How Nerves grow

In a makeshift laboratory in her bedroom, during the dark years of Mussolini's rule, Rita Levi-Montalcini laid the foundation for a great research career – and in 1986 she was awarded the Nobel Prize for her discovery of the nerve growth factor.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Herbert Schwegler

Published: 28.09.2012

Difficulty: intermediate

- As a Jew, Rita Levi-Montalcini was banned from working during the Mussolini era and was not allowed to work as a scientist or doctor. She set up an improvised laboratory in her bedroom at home.

- During World War II, she fled to the countryside with her family. When the German Wehrmacht invaded Italy, she went into hiding and survived thanks to the help of friends and partisans.

- After the war, she accepted Viktor Hamburger's invitation to conduct research in his laboratory in the USA. She investigated how nerve growth in chicken embryos is influenced by the body's periphery.

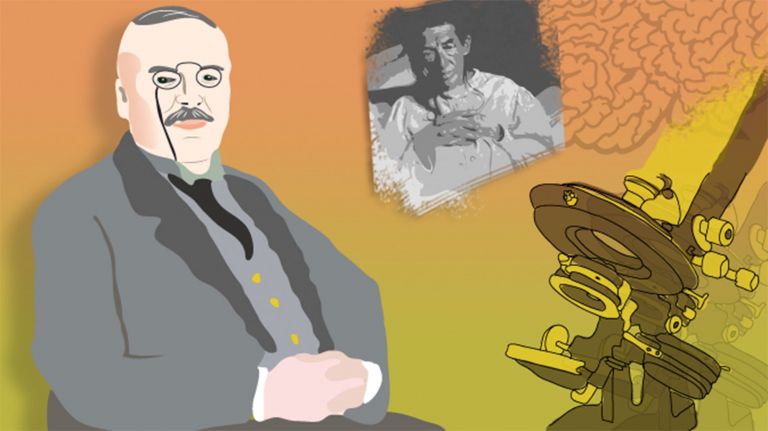

- Levi-Montalcini discovered that a signal emanates from a mouse tumor that causes neurons to form extensions. She calls the signal nerve growth factor (NGF). Her laboratory colleague Stanley Cohen succeeds in analyzing the molecule.

- She receives the Nobel Prize in Medicine together with Cohen for the discovery of NGF.

April 22, 1909 Rita Levi-Montalcini is born in Turin

1936 Completes her medical studies

1939–1940 Research stay in Brussels

1940–1943 Research in a makeshift bedroom laboratory

Fall 1943–August 1944 Lives underground in Florence

1947–1977 Works at Washington University in St. Louis, USA

1952 Publication of the first study on nerve growth factor

1986 Awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine

2001 Appointed senator for life in Italy

December 30, 2012 Levi-Montalcini dies in Rome

On her 100th birthday, she said that her brain worked better today than it did when she was 20. Rita Levi-Montalcini received the Nobel Prize for her findings on the development of the nervous system in chickens. And it is rumored that she may also owe her mental fitness to her research success – if the anecdote told by her fellow researcher Pietro Calissano to The Independent is true: Levi-Montalcini had been using eye drops she had developed herself for decades, which contained the nerve growth factor NGF. And that is precisely the substance that the researcher had discovered and which made her name in neuroscience forever. She died in Rome on December 30, 2012.

Anyone could see for themselves how mentally fit the researcher was: there are two interviews with Rita Levi-Montalcini on the internet, one from 1996 with the Society for Neuroscience (SFN) and one from 2009 with the Nobel Foundation – she was a hundred years old then. In both videos, she talks very impressively about her life – in English and with a strong Italian accent. Although she tends towards repetition, she expresses herself precisely and with the self-confidence of a scientist who has been successful for decades.

Banned from working during the Mussolini era

The road to fame was long and rocky. As a trained physician who had chosen to pursue a career in science, Levi-Montalcini found herself facing ruin in 1940. Her home country of Italy was ruled by the fascist Benito Mussolini, and as a Jew, she had been banned from practicing medicine and conducting research for years. She initially continued her scientific career in Brussels, but when Germany under Adolf Hitler invaded Belgium, she fled to her family in Turin.

There she looked for meaningful work, but everything she found exciting was forbidden to her: she was not allowed to enter universities or libraries, nor was she allowed to pursue any public work. “It had to be an activity that did not require support from the Aryan world outside,” Levi-Montalcini wrote in an autobiographical article for the Nobel Committee. “My inspiration was a 1934 scientific article by Professor Viktor Hamburger.” The German developmental biologist had been conducting research for some time in exile at Washington University in the United States. And it was in his research group that Levi-Montalcini would make her decisive scientific breakthrough years later.

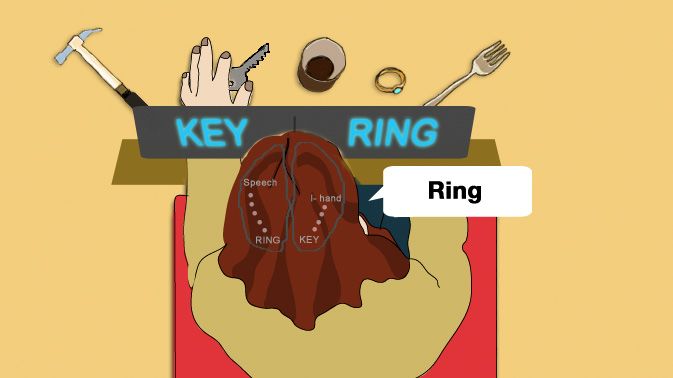

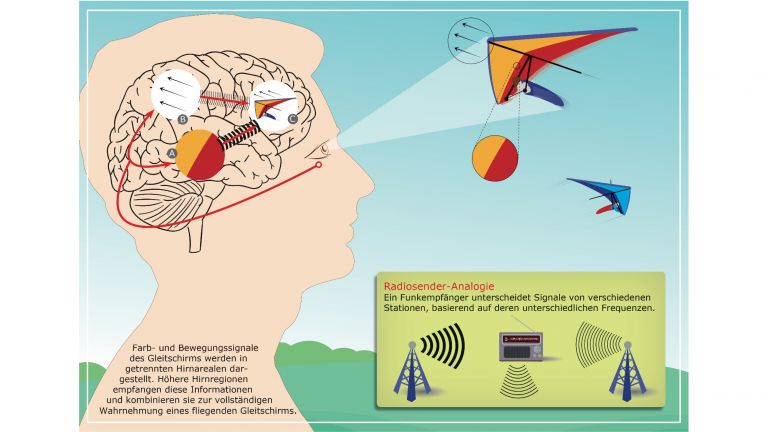

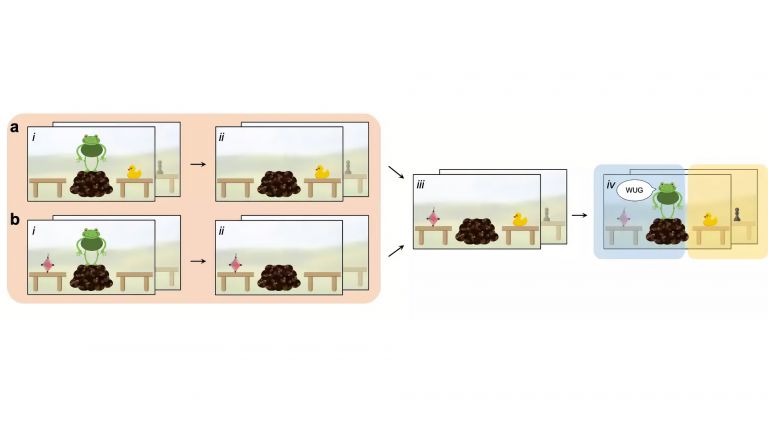

In the publication in question, Hamburger described his experiments with chicken embryos. He removed their wings and found that the nerves that normally grow into the limbs stopped growing. Many even died. This made Levi-Montalcini curious: something must have told the cells that the wings were missing, that they now had no purpose. What was it? Could it be that the body's periphery, such as the wings, sends out signals to attract nerve fibers? The scientist was determined to understand and continue Hamburger's research.

Improvised laboratory in the bedroom

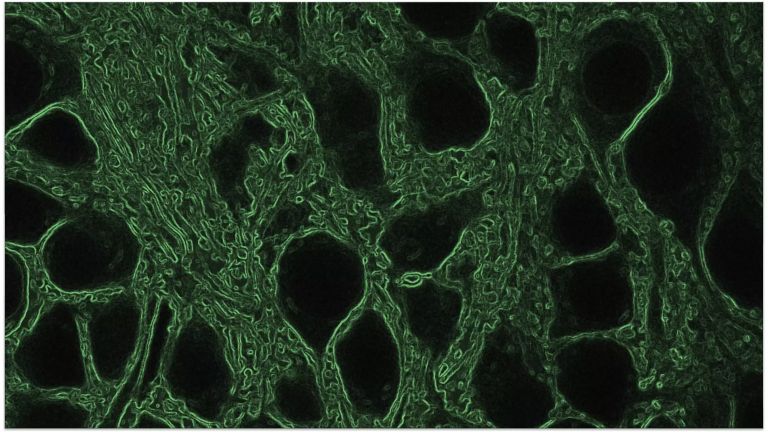

She was no longer allowed to use her old laboratory, so Levi-Montalcini set up an improvised laboratory in her tiny bedroom, where she worked “under conditions similar to those of Robinson Crusoe,” as she recalled decades later in an interview with biologist Giovanni Giudice. Instead of manipulating the tissue of chicken embryos with specially made glass scalpels, she made do with sewing needles, which she sharpened into scalpels. She converted a stove into an incubator. After the experiments, her family got to eat the eggs she worked with.

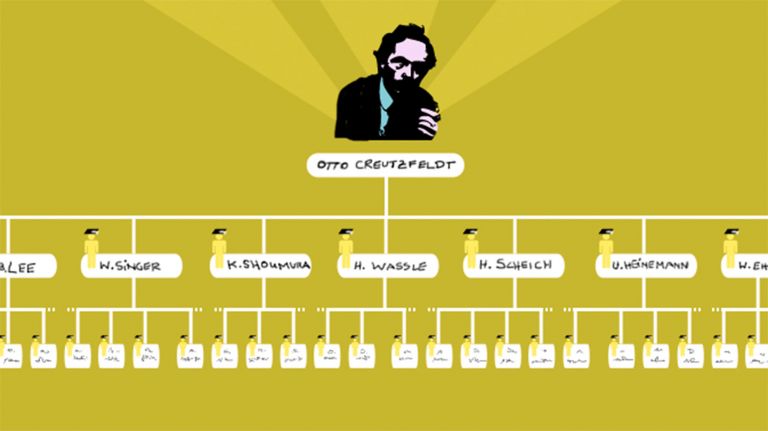

Soon, the researcher received reinforcement from an overqualified assistant, Giuseppe Levi, who had also fled from Belgium to his homeland to escape the Nazis. He was Levi-Montalcini's professor during her medical studies, and in her Nobel Prize speech in 1986, she honored him as an outstanding researcher and a great inspiration for her work. And he inspired not only her. Two more of his students were awarded the Nobel Prize: Salvador Luria and Renato Dulbecco, both for their work with viruses.

When the war began in Italy, the Allies bombed Turin and the family fled to the countryside. They found shelter in a hut, where Levi-Montalcini immediately set up her small private laboratory again. “There was an incredibly hostile atmosphere towards Jewish people at the time, but I didn't care. There was still hardly any physical violence. I continued my research and completely ignored what was happening around me,” she recalls in the aforementioned interview with the SFN. But that didn't last long: since the German Wehrmacht invaded in 1943, all Jews in Italy were in mortal danger. The Levi-Montalcini family fled to Florence, went into hiding there, and survived thanks to the support of friends and partisans.

Recommended articles

Invitation from the USA

A few years after the war, Levi-Montalcini received a letter that would prove decisive for her outstanding research career. The letter was addressed to Giuseppe Levi, her assistant during the dark Mussolini years. He was now her boss again at the University of Turin, and she was his assistant professor. The letter came from the USA – from Hamburger. “It was a lovely letter, and I still have it today,” says Levi-Montalcini in the SFN video. “I know that you have a young woman working on the same problem that I have been working on since 1934,” wrote Hamburger. “Could she come and work with me for a few weeks or months?”

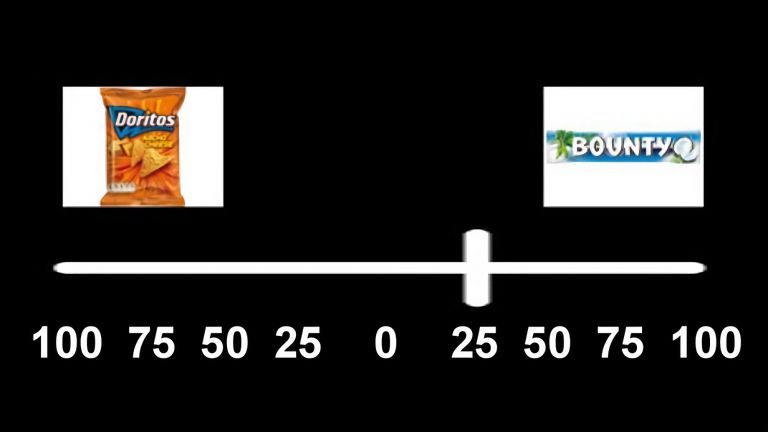

A few weeks turned into 30 years. It was still the same question that had fascinated Levi-Montalcini during the war years: Why do nerves in chicken embryos stop growing when the wings or legs are removed? And conversely, why do nerves grow into a wing structure that is transplanted from one embryo to another? How do nerve cells know where they are needed?

At first, the researcher was no closer to finding the answer. It was only after three years that the decisive turning point came, as she recalls in the SFN video: “One winter morning in 1950, Viktor Hamburger called me over; our laboratories were right next to each other.” He told her about a strange observation made by one of his former students: Elmer Bücker had transplanted a tumor fragment from a mouse into a three-day-old chicken embryo. The result: the embryo's sensory nerves grew into the tumor.

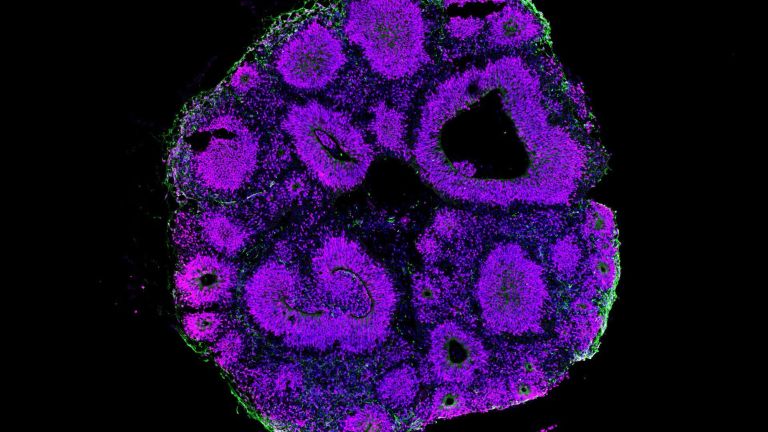

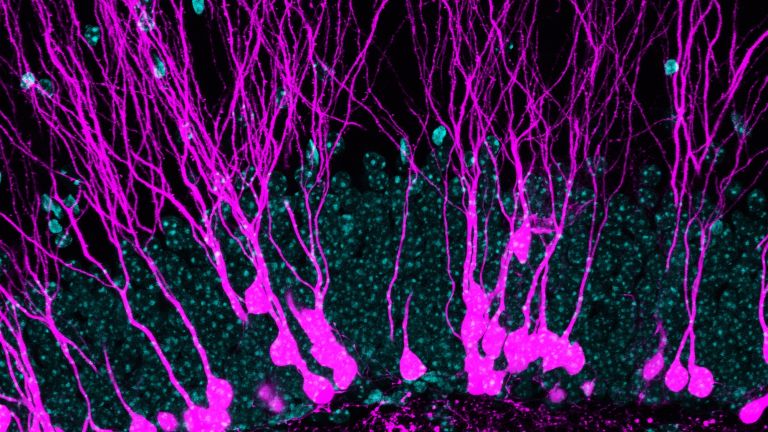

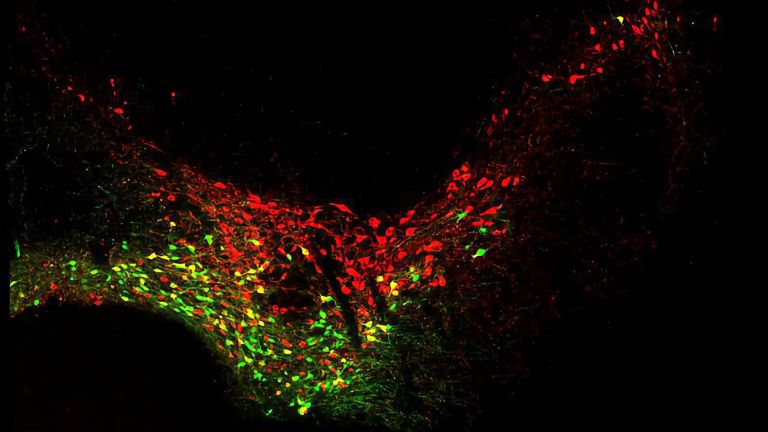

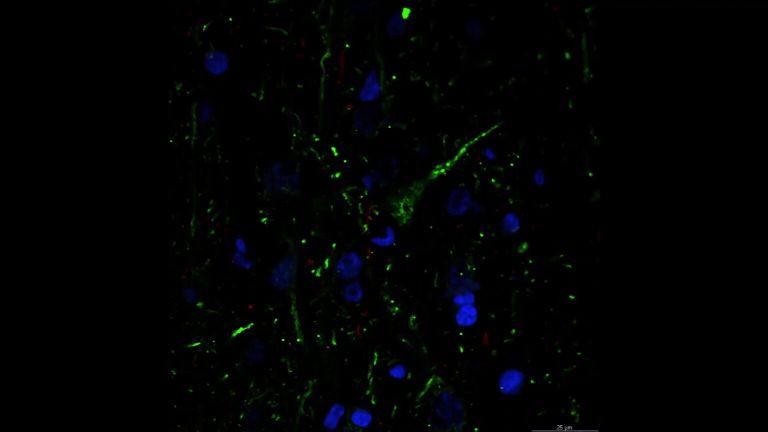

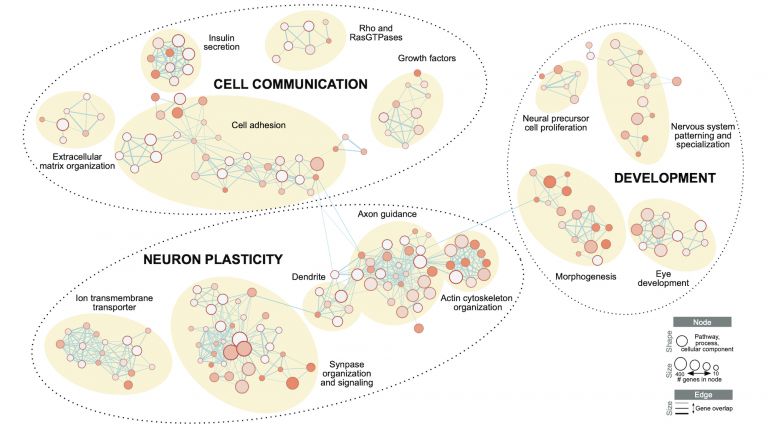

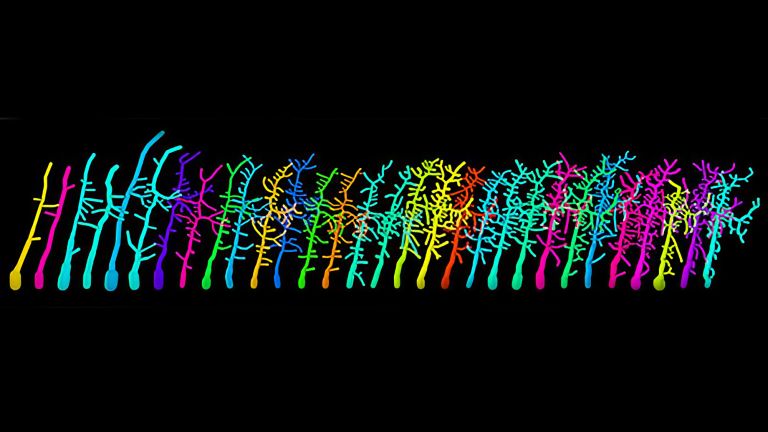

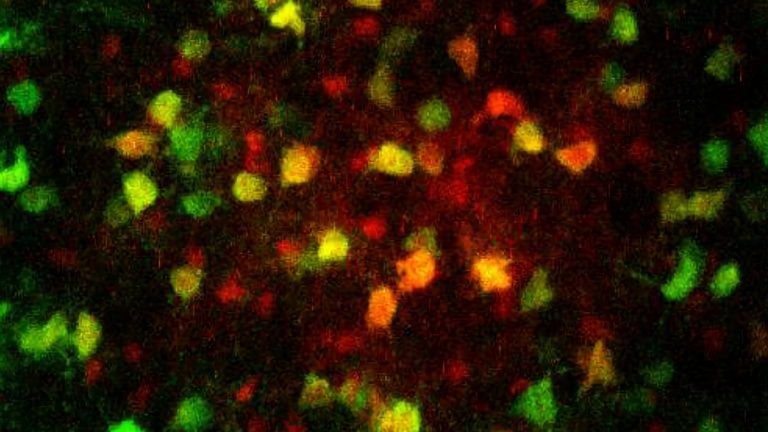

Levi-Montalcini was electrified. Could it be that the mouse tumor was emitting a signal that attracted the nerve cells? She repeated Bücker's experiments and came to the same conclusion. And she discovered that the tumor emitted a soluble chemical signal with amazing capabilities. When tiny amounts of it are added to cultured nerve cells, nerve fibers sprout after just a few minutes. She later named the signaling substance “nerve growth-promoting factor” (NGF).

She soon received support for her research from a biochemist friend, Stanley Cohen, who later shared the Nobel Prize with her. The research duo first discovered that NGF is found in many tissues and body fluids – including snake venom and mouse saliva. Cohen isolated and analyzed the substance and found that it is a protein consisting of 118 amino acids.

NGF eye drops

With her NGF, Levi-Montalcini was the first to show how chemical signals influence the formation of neural networks. NGF was also the first in a whole series of growth factors whose discovery led scientists to one of the great mysteries of life: how a single egg cell becomes a complex organism.

But what about the NGF eye drops that Levi-Montalcini allegedly took daily and which are said to explain her mental fitness? At least in theory, the effect is plausible: research over the last few decades has shown that NGF also plays an important role in adults, supporting the constant remodeling processes in the brain. NGF signals to neurons that they should continue to live. If the factor is missing, they die. However, whether eye drops containing the signaling substance can actually have a positive effect on the scientist's brain has not yet been investigated – and the whole thing is just an unconfirmed anecdote.

Rita Levi-Montalcini died on December 30, 2012, in Rome.

Further reading

- Aloe, L: Rita Levi-Montacini: the discovery of nerve groth factor and modern neurobiology. Trends in Cell Biology. 2004; 14(7):395 — 399 (zum Text).

- Levi-Montalcini, R.: Praise of Imperfection: My Life and Work. Basic Books, 1988.

- [Update 26.7.2013] Chao M et al. Rita Levi-Montalcini: The story of an uncommon intellect and spirit. Neuroscience (2013) (zum Text).