From Sound to Interpretation

Amazing signal conversion: How the ear extracts information about the nature and origin of sound from rapid fluctuations in air pressure, thereby revealing its meaning to us.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Steven van de Par

Published: 03.10.2025

Difficulty: serious

- The inner ear encodes pitch by stimulating sensory cells in different locations with different frequencies. This principle of location (tonotopy) is also found elsewhere in the auditory pathway.

- Higher volumes cause the neurons involved to fire in faster succession, and more neurons to be active.

- The brain obtains directional information from differences in volume and transit time between the two ears, as well as from changes in the sound image. These are caused by spatial conditions and the geometry of the head and ear cups.

- Neurons with highly diverse specializations are involved in the various stages of auditory signal processing in the brain. Many of the connections between them have not yet been researched.

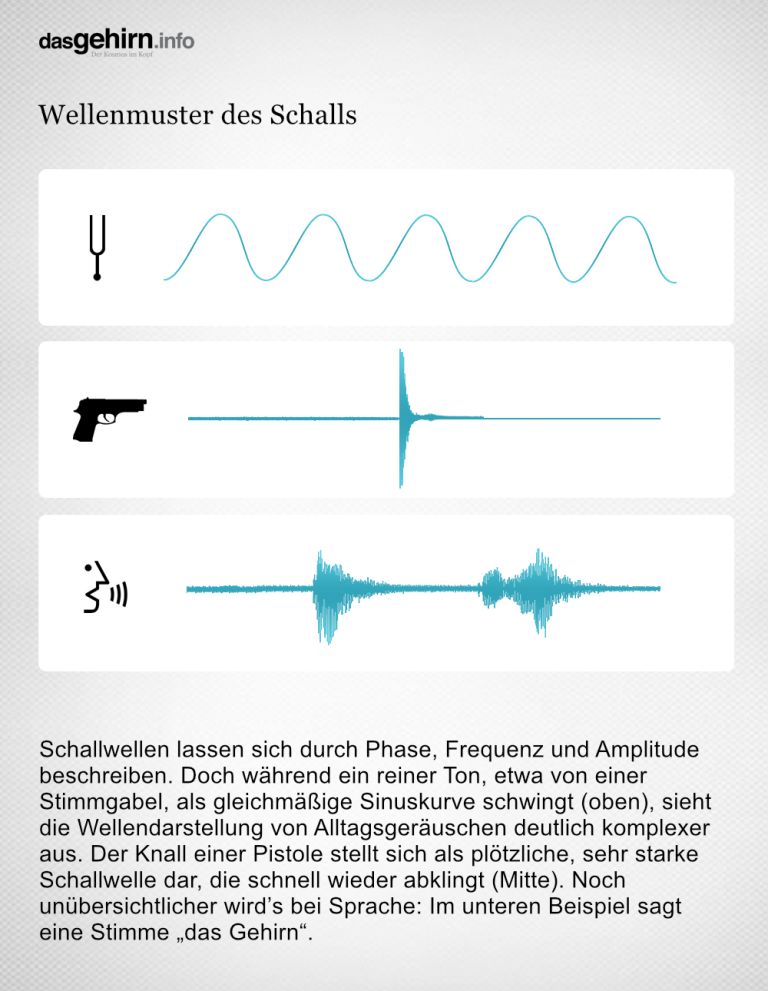

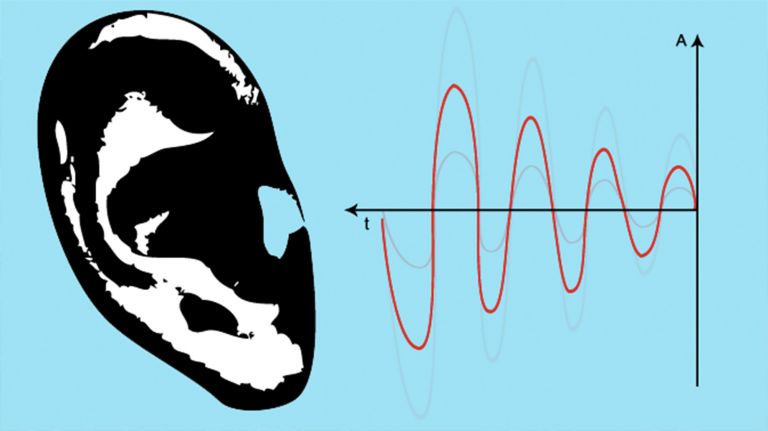

Even though sound always reaches us in the form of rapid fluctuations in air pressure and is therefore physically always more or less the same phenomenon, different types of sound are distinguished depending on their temporal progression. The simplest variant is a tone: a pure vibration of a single frequency with the waveform of a sine curve. A sound, on the other hand, consists of a tone plus harmonics, i.e., in addition to the fundamental tone (or tones), it also contains components with double, triple, or multiple frequencies. The waveform is thus more complex than that of a tone, but still regular: it repeats itself periodically. Depending on the ratio in which the overtones are composed, a sound can resemble a flute, violin, organ, and so on. If the waveform is not periodic but completely irregular, it is referred to as a noise. This includes any form of noise, but also the sound that leaves the mouth when speaking. Finally, there is the bang as a special form of noise. It is characterized by a very sudden increase and rapid decrease in amplitude.

Is the wind rustling in the leaves or is there a dangerous animal rustling in the bushes? Is the thunder rumbling in the distance or is the storm already so close that it's time to find shelter? Who closed the door in the next room, and were they possibly angry? The ear is able to extract a wealth of information from sound – based solely on the fluctuations in air pressure that reach the ear.

Anyone who has ever had the opportunity to view audio files in waveform on a computer screen can appreciate how amazing this ability is: a seemingly chaotic up and down. While we perceive a simple sine wave as a pure tone, the sound waves of real noises, such as speech or music, overlap to form a confusing jumble.

Division of labor among sensory cells

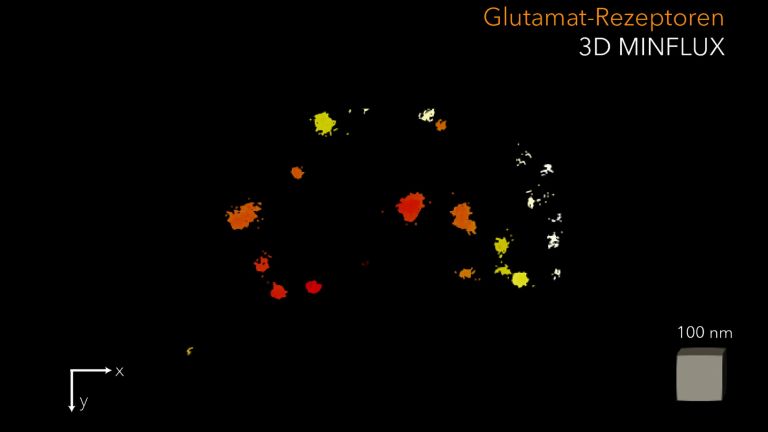

Sound waves can be described solely by their frequency and amplitude. The frequency indicates how often the oscillation repeats within a second and reflects the pitch. The amplitude expresses the deflection with which the wave oscillates around its rest position. It is a measure of sound pressure and thus of volume. This also applies to the most complex waveforms, such as those created by a babble of voices, the background noise in a shopping mall, or a piece of music: it is always mathematically possible to break them down into their individual components, i.e., into many sine or cosine curves of different frequencies and amplitudes.

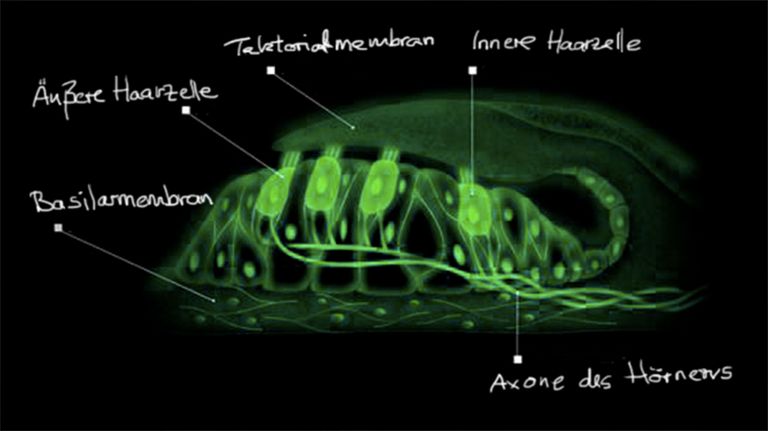

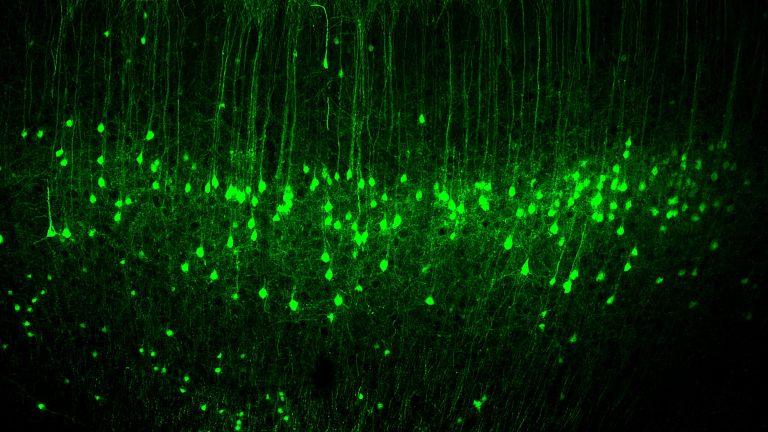

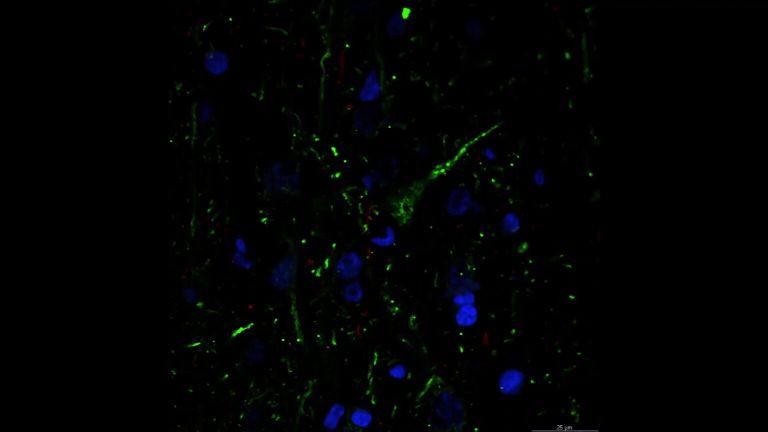

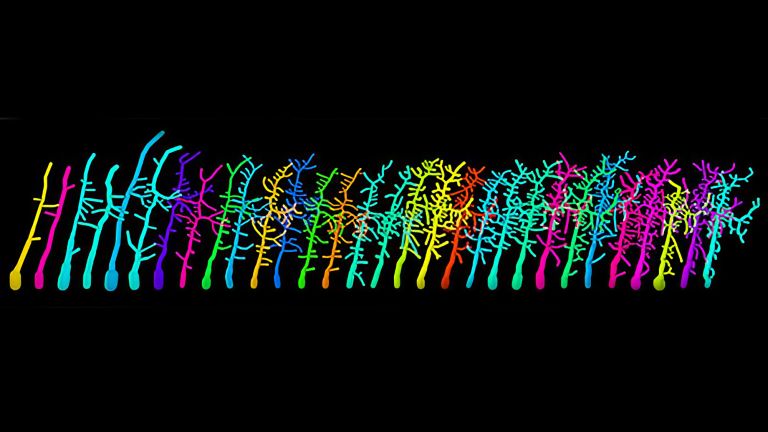

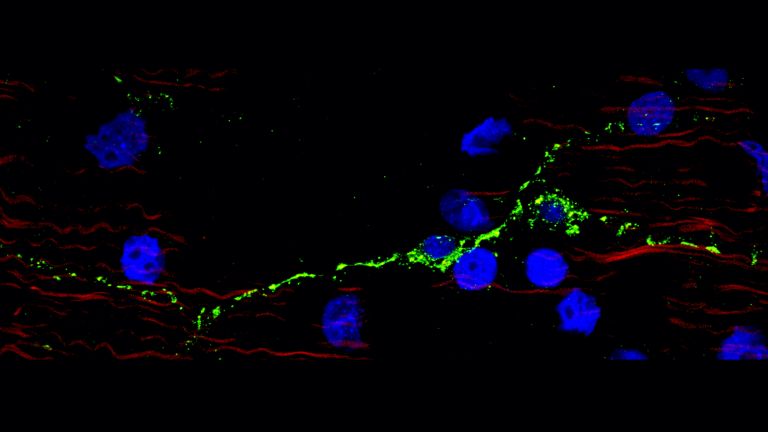

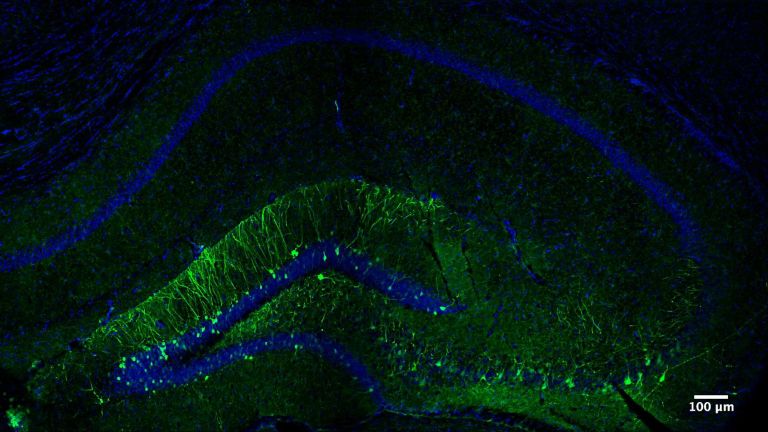

The ear also performs this analysis. The basilar membrane plays a crucial role in this process. It picks up the vibrations and transmits them to the organ of Corti, where hair cells receive the mechanical information and translate it into a neurological signal that travels up the auditory pathway.

The basilar membrane in the cochlea, which is a good three centimeters long, is narrow and stiff at one end and wide and soft at the other. High-pitched sounds trigger resonant vibrations near the narrow, stiff end and stimulate the hair cells located there. Low-pitched sounds, on the other hand, cause the greatest deflection at the other end, so that completely different nerve cells receive impulses. With a mixture of frequencies, the cells become active at several points simultaneously. In principle, the basilar membrane of an unrolled cochlea can be imagined as the keyboard of a piano, on which the different notes are arranged next to each other.

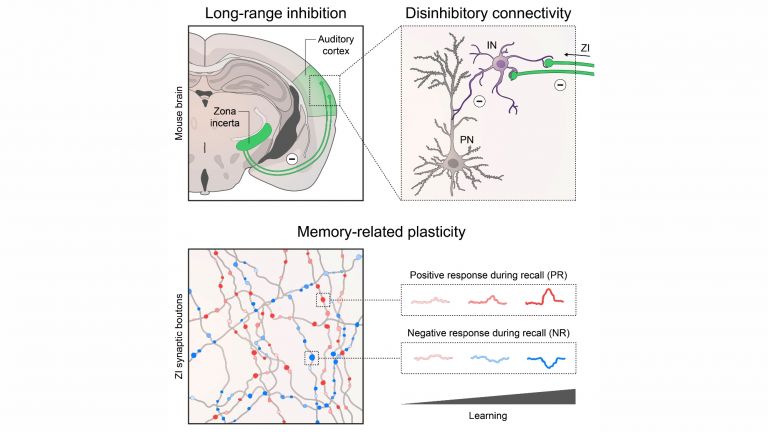

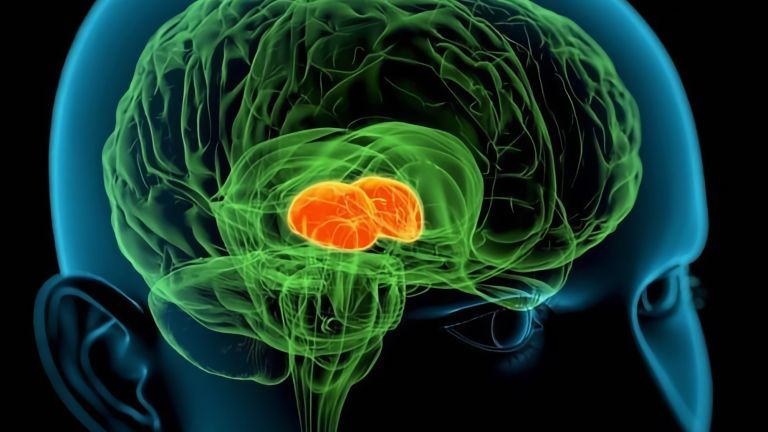

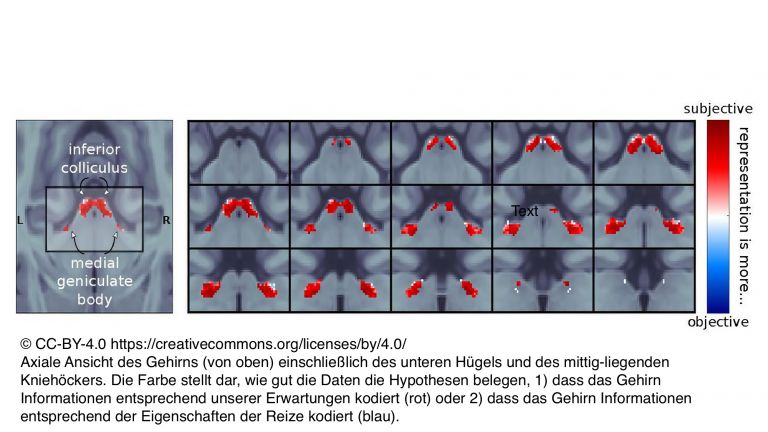

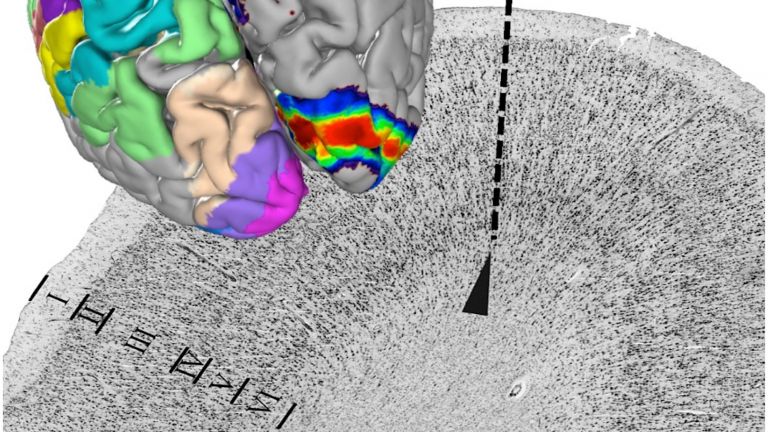

This systematic organization of characteristic frequencies is called tonotopy. It is widespread in the auditory system. Tonotopic maps are found not only in the basilar membrane, but also in all auditory relay nuclei that filter and transmit sound information, in the medial geniculate nucleus (MGN) of the thalamus, which projects into the auditory cortex, and in the auditory cortex itself. Specialized nerve cells are therefore responsible for processing sounds of a certain frequency. When it comes to pitch, there is a division of labor.

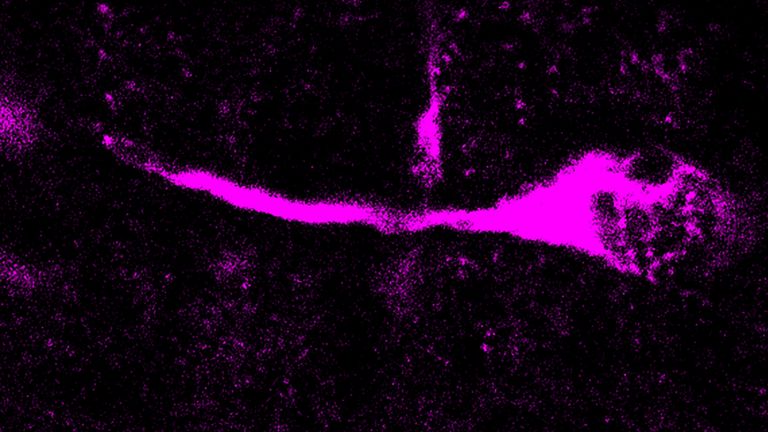

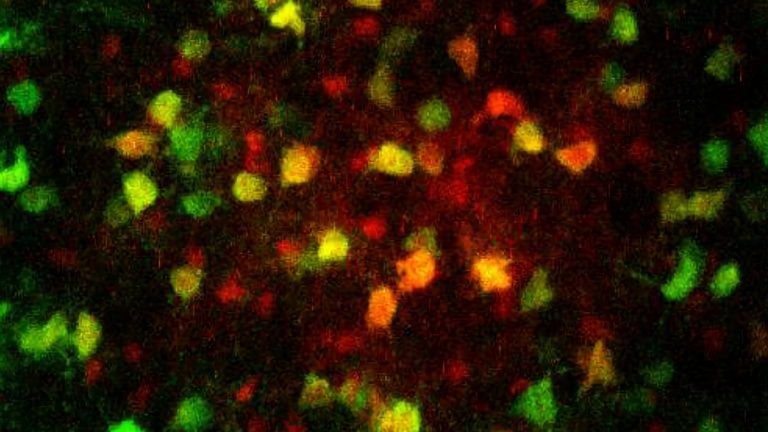

Translation of volume

The neurons translate the amplitude, i.e., the volume of the individual frequency components, into different firing rates: the more intense the vibration, the faster the nerve cells responsible for the respective frequency generate action potentials. In addition, there are neurons that “ignore” quiet sounds, so to speak, and only start firing at higher volumes. Furthermore, very loud sounds with large amplitudes in the Corti organ also cause neighboring hair cells to vibrate, which in turn activate downstream neurons.

Sound intensity is therefore represented by a combination of firing rate and number of neurons involved. This makes it possible to encode the huge range of volumes that our hearing covers. When a rock concert roars at the audience at 120 decibels, the air pressure fluctuations of the sound are ultimately a million times stronger than at the hearing threshold of zero decibels.

Recommended articles

Two ears hear more than one

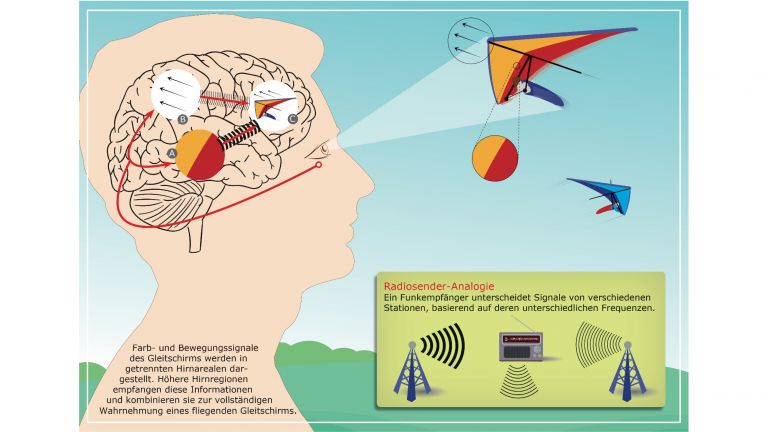

However, what the waveform alone does not reveal is the direction from which a sound is coming. In order to pick up this often-crucial information, the auditory system combines three mechanisms.

The most obvious is probably the difference in intensity. The head casts a kind of acoustic shadow, especially with high-frequency sound waves: if the sound source is on the right, we hear the sound slightly more quietly on the left than on the right.

However, directional localization based on intensity difference fails with low-pitched sounds: in this case, the wavelength is large and the sound can travel around the head virtually unhindered. In this case, the time difference becomes particularly important: due to the speed of sound in air, a sound wave coming from the right reaches the right ear about 0.0006 seconds earlier than the left ear. The neurons that receive signals from both ears also use this tiny delay of time to locate the source of the sound.

There are areas in the brain stem that process input from both ears, as well as in the higher auditory areas. This allows even small differences in intensity and time to be perceived and translated into directional information. We obtain further important information from the absolute intensity of a sound, as it decreases rapidly with increasing distance.

Subtle variations in the sound image

However, neither intensity nor time differences explain why we can also differentiate whether sounds come from diagonally in front on the right or diagonally behind on the right – or even from above or below. This is where the third mechanism comes into play: the shape of the head and, above all, the outer ears create a complex pattern of sound shadows and sound shadow reflections that vary depending on the frequency and direction of the incoming sound. For example, the outer ear attenuates high frequencies more than low frequencies when sounds come from behind. A bang behind us therefore sounds somewhat duller than when something explodes in front of us. And if the bang comes from above, the frequency response is slightly different again. The brain knows how to interpret these subtle variations in such a way that it recognizes the direction.

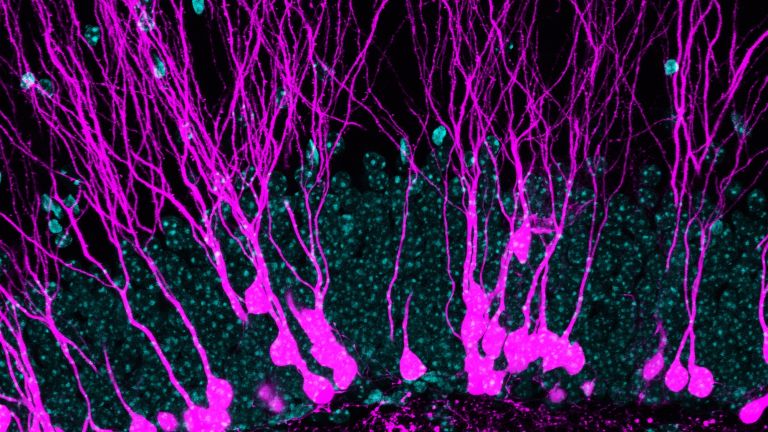

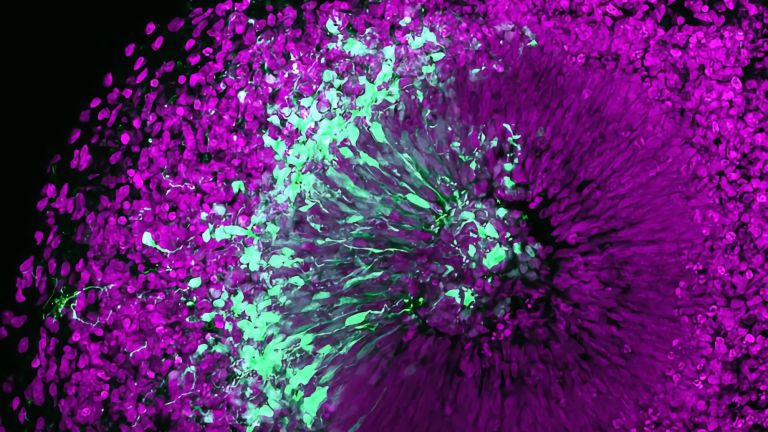

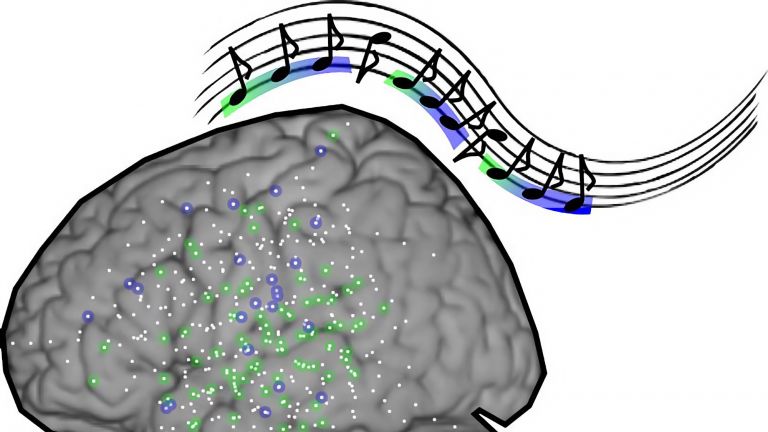

Now the sound we hear is neatly broken down into its frequency components and its spatial origin is clarified. At least roughly, we know which paths the signals then take through the various parts of the brain: the cochlear nuclei, the “upper olive” and “lower mounds” in the brain stem, the medial geniculate nucleus in the diencephalon, and the auditory areas of the cortex. And along the way, further steps are taken toward fine differentiation.

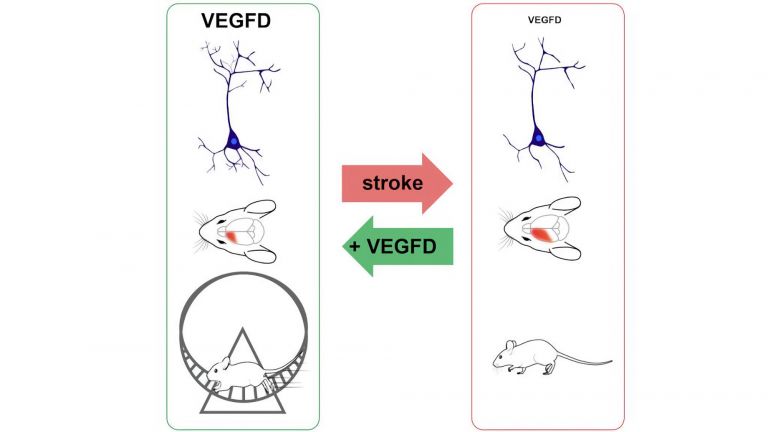

It is clear that the neurons involved have very different specializations: some fire as long as a sound of a certain frequency is heard, others only when it begins and/or ends. Some neurons compare the signals from both ears, others react selectively to certain intensities, and still others comb through everything they hear for specific sound patterns.

Taken together, this ultimately enables the finest distinctions: we can identify events by the type of bang, people by the sound of their footsteps, moods by the tone of a voice. At the same time, what we hear triggers a wide variety of thoughts, emotions, and behaviors: Is the person we are talking to speaking in a friendly or aggressive tone? Is the music sad or does it make us want to dance? Do we tune out ambient noise as meaningless, or does the crack of a twig – say, at night in the forest – fill us with fear and terror?

This further processing can affect almost every aspect of our mental state. But as commonplace as it may seem to us that sensory perceptions spark new ideas or influence our mood, the actual music of hearing has so far eluded comprehensive scientific description and categorization – a vast field full of open questions and mysteries in brain research.

First published on September 17, 2012

Last updated on October 3, 2025