From Sound to Word

The ability to produce and understand language makes humans unique in evolution. Brain research has shown that areas in and below the cerebral cortex are involved in language processing.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Katharina von Kriegstein

Published: 13.10.2023

Difficulty: intermediate

- Individual groups of neurons are sensitive to the phonemes of human speech.

- In the cerebral cortex, parts of the frontal and temporal lobes are important for language comprehension (receptive language) and production (expressive language).

- The brain can distinguish speech from other sounds based on characteristic frequencies, among other things.

frontal

An anatomical position designation – frontal means "towards the forehead," i.e., at the front.

The phone rings, and all you hear on the other end is a brief “hello” – yet you have no problem recognizing your husband or even your boss by his voice. Some people, however, lack this ability to recognize the distinctive features of a voice and associate it with a familiar person. This disorder, known as phonagnosia, could be related to damage to regions such as the right temporal lobe, which appear to process voices selectively. Until recently, phonagnosia was only observed as a consequence of strokes. But in 2009, researchers at University College London discovered a possibly congenital form in a 60-year-old patient, referred to as “KH.” No anatomical defects were found in the patient. “KH” cannot learn unfamiliar voices, nor can she recognize the voices of people she knows.

There are only two sounds, both identical and incredibly simple – but when the expectant listener hears their offspring babble something like “Pa-Pa” for the first time, it triggers a fireworks display of emotions. The little one is hugged, cuddled, and proudly shown off. Touching, but also a reaction to a – pardon me! – rather random event. After all, the child has surely tried out similar syllables countless times before, such as “ba,” “ma,” or “da”.

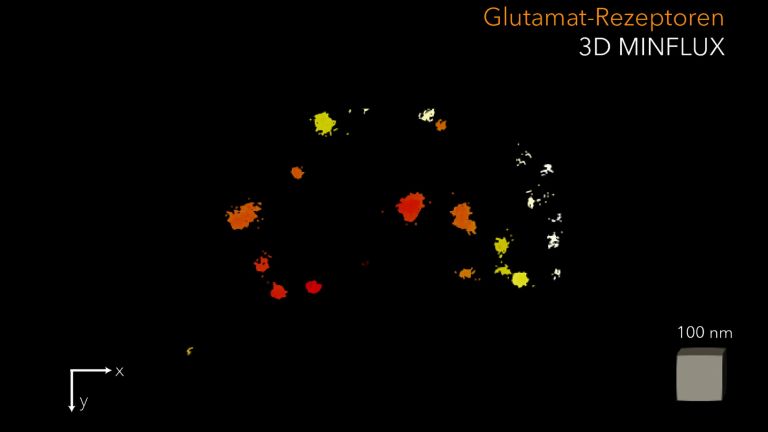

Similar syllables such as “ba” and ‘pa’ differ only in what linguists refer to as the most elementary linguistic unit, the distinctive features.” Even in the brains of monkeys, researchers have been able to identify nerve cells that respond sensitively to such phoneme-distinguishing features of an acoustic stimulus, i.e., they respond to a sound like “ba” but not to “pa.” In humans, it is probably individual groups of neurons that are able to recognize the approximately 100 phonemes of the linguistic alphabet from which all known languages can be composed.

But human language is more than just recognizing successive phonemes. It is not for nothing that it is only when the baby says “Pa” twice that the father melts, because only then does it become recognizable as meaningful. Even if the offspring did not mean this bearded guy with his babbling, the proud father's brain interprets a deep meaning into these two syllables. Just as the moody, reproachful “Dad” of the later teenager will take on a completely different meaning. And once the child starts speaking in coherent sentences, Dad is recognized grammatically as sometimes the subject and sometimes the object.

emotions

Neuroscientists understand "emotions" to be complex response patterns that include experiential, physiological, and behavioral components. They arise in response to personally relevant or significant events and generate a willingness to act, through which the individual attempts to deal with the situation. Emotions typically occur with subjective experience (feeling), but differ from pure feeling in that they involve conscious or implicit engagement with the environment. Emotions arise in the limbic system, among other places, which is a phylogenetically ancient part of the brain. Psychologist Paul Ekman has defined six cross-cultural basic emotions that are reflected in characteristic facial expressions: joy, anger, fear, surprise, sadness, and disgust.

Central language areas: syntax and semantics

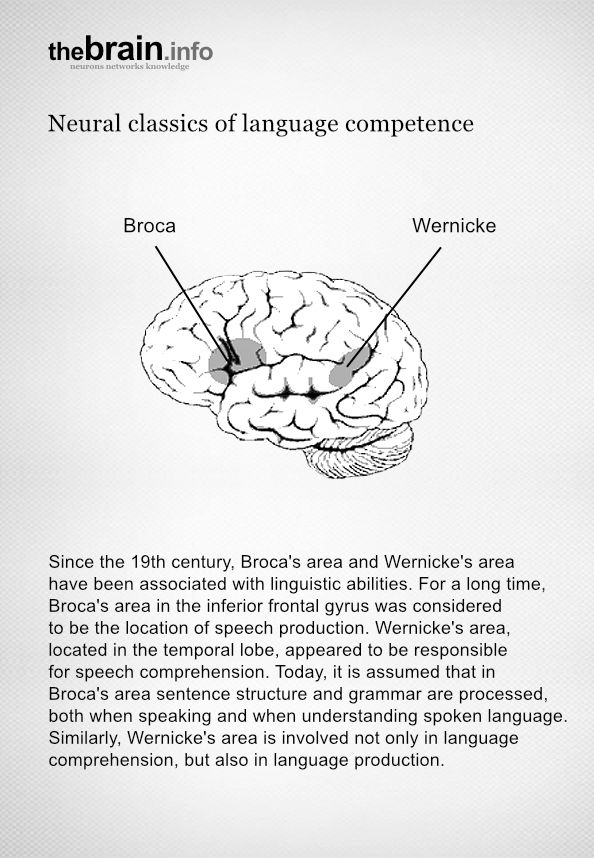

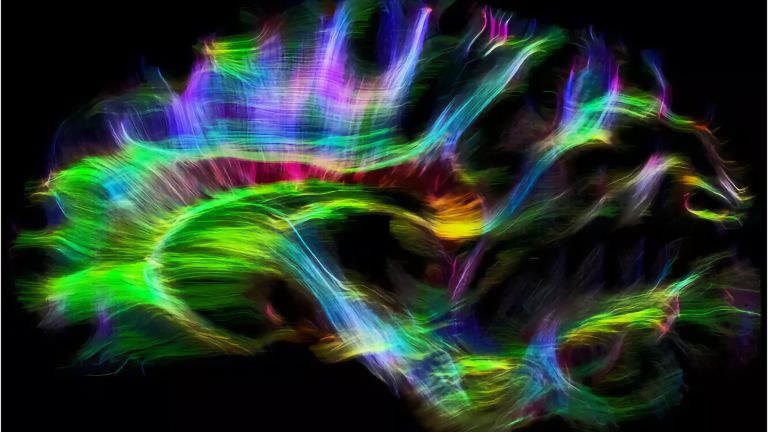

Until the 1970s, the Broca's area in the inferior frontal gyrus and the Wernicke's area, which is usually located in the left Temporal lobe in right-handed people but more often on the right in left-handed people, were considered primarily responsible for all these linguistic cognitive functions. This was mainly the result of studies of patients with brain injuries such as strokes. According to these studies, Broca's area seemed to be primarily responsible for speech production and Wernicke's area for speech comprehension. However, more recent research shows that this clear distinction does not exist.

After more detailed examinations, patients with Broca's-related speech disorders (expressive aphasia) usually also have difficulties understanding language, for example, differences in sentence structure and syntax. Therefore, it is now assumed that sentence structure and grammar are processed in the Broca's area – both for speaking and for understanding spoken language. The situation is similar for patients with damage to the Wernicke area (receptive aphasia), which, according to current understanding, may be a connection point between linguistic and semantic information. Patients with damage to the Wernicke area do not always understand words correctly when listening. They also mix up words when speaking, saying “pear” or “biting fruit” instead of “apple,” for example.

Broca's area

An area of the prefrontal cortex (cerebral cortex) that is usually located in the left hemisphere. Plays a key role in the motor production of speech. First described by French neurologist Paul Pierre Broca in 1861.

inferior

An anatomical position designation – inferior means located further down, the lower part.

frontal

An anatomical position designation – frontal means "towards the forehead," i.e., at the front.

Temporal lobe

Lobus temporalis

The temporal lobe is one of the four lobes of the cerebrum and is located laterally (on the side) at the bottom. It contains important areas such as the auditory cortex and parts of Wernicke's area, as well as areas for higher visual processing; deep within it lies the medial temporal lobe with structures such as the hippocampus.

Not just unilateral activity

As a rule, most language processing takes place in the left Hemisphere of the brain, but bilateral activity can also be observed for certain tasks. Studies of patients with injuries to the corpus callosum, which connects the two hemispheres of the brain, show that the right hemisphere is apparently necessary for processing acoustic features that span sounds, such as accent or intonation. A 2008 study by researchers at Berlin's Charité hospital indicates that cooperation between the cerebral Cortex and the thalamus is necessary for recognizing sentence structures and content. In general, it is becoming increasingly clear that not only Broca's and Wernicke's areas are involved in language processing, but also other areas of the cerebral cortex and those below the cerebral cortex, including possibly the basal ganglia.

Hemisphere

The cerebrum and cerebellum each consist of two halves – the right and left hemispheres. In the cerebrum, they are connected by three pathways (commissures). The largest commissure is the corpus callosum.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Recommended articles

From form to content

The path that language takes through the brain until it becomes conscious to the listener is surprising. According to linguist Angela Friederici from the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences, the first thing that is examined is not the meaning, but the grammar of a sentence. Form before content: within 200 milliseconds, the adult brain analyzes nouns, verbs, prepositions, and other grammatical subtleties. In children, this takes up to 350 milliseconds – an indication that grammar rules must be learned, but then become automatic. Only in a second phase, up to 400 milliseconds later, does the brain finally interpret the meaning of the words. In the third phase, the analysis phase after 600 milliseconds, the brain has finally reconciled the grammar and semantics of a sentence.

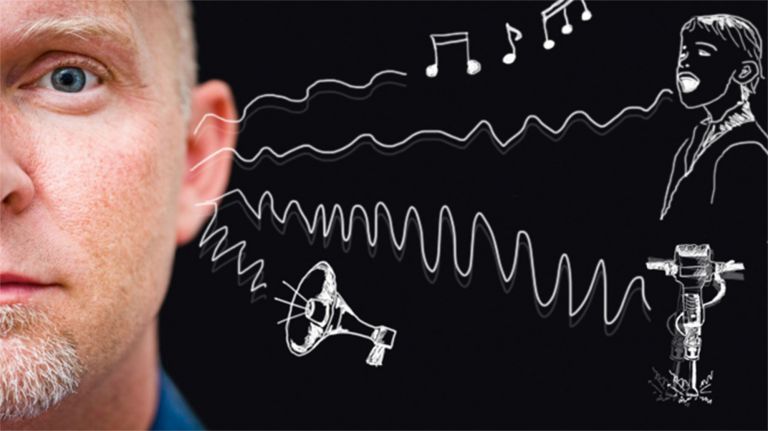

Distinguishing mere sounds from language

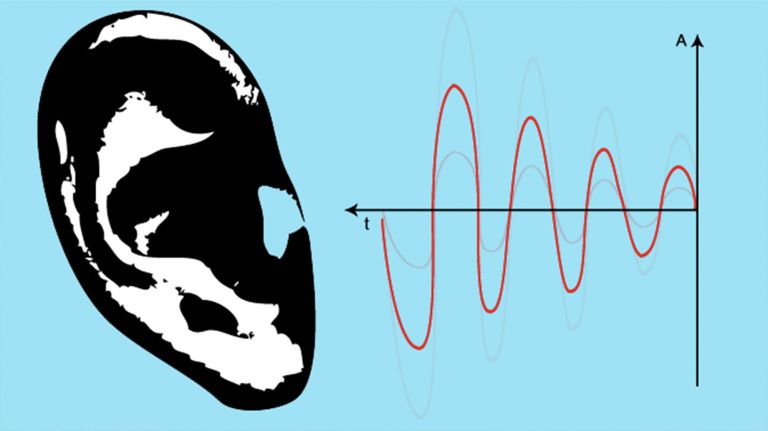

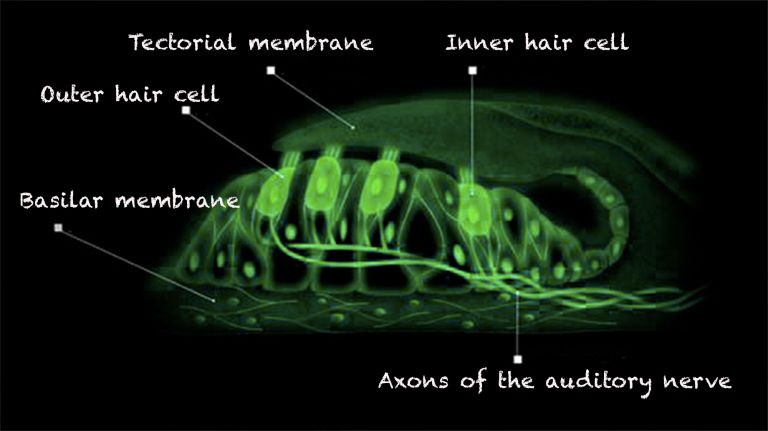

But how do parents recognize language in their child's babbling lip acrobatics and not just sounds? Apart from the parents' heightened expectations, what makes the difference between sound waves from the human vocal apparatus and those from musical instruments or cars? The Cochlea in the inner ear apparently has a counterpart in the brain, similar to the Retina of the Eye. High frequencies are processed by different groups of neurons – “fields” – in the Auditory cortex than lower frequencies.

And just as a jackhammer covers a characteristic frequency spectrum, human speech also occurs within a certain range: 80 Hz to 12 kHz, with the fundamental tone for men around 125 Hz, for women around twice that (250 Hz), and for children almost four times as high (440 Hz). For this reason alone, “Pa-Pa” is processed in part by different neurons than other sounds, be it music, noise, or just babbling.

Cochlea

The cochlea is the part of the inner ear that contains the organ of Corti, which is responsible for converting acoustic signals into nerve impulses.

ear

auris

The ear is not only the organ of hearing, but also of balance. A distinction is made between the outer ear with the auricle and external auditory canal, the middle ear with the eardrum and ossicles, and the actual hearing and balance organ, the inner ear with the cochlea and semicircular canals.

Retina

The retina is the inner layer of the eye covered with pigment epithelium. The retina is characterized by an inverse (reversed) arrangement: light must first pass through several layers before it hits the photoreceptors (cones and rods). The signals from the photoreceptors are transmitted via the optic nerve to the processing areas of the brain. The reason for the inverse arrangement is the evolutionary development of the retina, which is a protrusion of the brain.

The retina is approximately 0.2 to 0.5 mm thick.

Eye

bulbus oculi

The eye is the sensory organ responsible for perceiving light stimuli – electromagnetic radiation within a specific frequency range. The light visible to humans lies in the range between 380 and 780 nanometers.

Auditory cortex

The auditory cortex is a part of the temporal lobe that is involved in processing acoustic signals. It is divided into the primary and secondary auditory cortex.

First published on July 27, 2012

Last updated on October 13, 2023