Ringing in the ears

Not only does it get on your nerves, it also comes from there: researchers are increasingly convinced that tinnitus originates in the brain. The cause could be structural changes or overexcited neurons in the auditory cortex.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Christo Pantev, Prof. Dr. Christine Köppl

Published: 28.10.2025

Difficulty: serious

- Tinnitus is often triggered by a defect such as damaged Hair cells in the inner ear. However, researchers now believe that the actual cause lies in the brain.

- According to a widely accepted theory, tinnitus is caused by structural changes in the brain: the frequencies that are still intact in the normal hearing range are overrepresented in the auditory cortex, resulting in ringing.

- It is possible that other areas of the brain besides the Auditory cortex are involved in the development of this nerve-wracking noise. Limbic regions, for example, could contribute to the negative emotional coloring of the ringing in the ear.

- At least chronic tinnitus is considered incurable. Therapies such as retraining therefore aim to help those affected get used to the ringing in their ears and thus attach less importance to it.

Hair cells

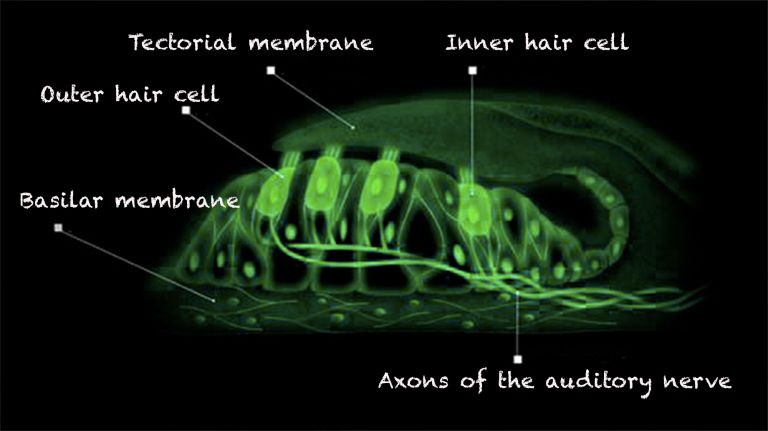

Sensory cells in the inner ear located in the organ of Corti and the semicircular canals. The hair cells in the organ of Corti are responsible for transducing (converting) the vibrations into electrical potentials. Each of these sensory cells has hair-like protrusions of varying lengths, called stereocilia. These are interconnected. The movement of these stereocilia caused by the vibrations is the key to signal transduction in the hair cells.

ear

auris

The ear is not only the organ of hearing, but also of balance. A distinction is made between the outer ear with the auricle and external auditory canal, the middle ear with the eardrum and ossicles, and the actual hearing and balance organ, the inner ear with the cochlea and semicircular canals.

Auditory cortex

The auditory cortex is a part of the temporal lobe that is involved in processing acoustic signals. It is divided into the primary and secondary auditory cortex.

In addition to retraining, there are other treatment options such as biofeedback: Muscle biofeedback is often used for tinnitus patients. The patient receives visual or acoustic feedback on the tension in their muscles or muscle groups and is asked to try to relax the muscles based on this feedback. If this is successful, the ringing in the ears can also be reduced in some tinnitus patients. This is particularly possible in cases of accompanying muscle tension in the neck or jaw area or in cases of stress.

Subjective tinnitus can only be perceived by the person affected. It is thought to be caused by a processing error in the brain. Objective tinnitus, on the other hand, is caused by a specific medical condition. In this case, a doctor can detect the whistling sound when listening with a stethoscope. However, objective tinnitus is a very rare phenomenon.

Just a moment ago, the music was lively and jubilant. But suddenly it stops and a shrill tone on the violin begins to get on your nerves: in String Quartet No. 1 in E minor, “From My Life,” Bohemian composer Bedřich Smetana (1824–1884) set the noise in his ears that plagued him to music. “The greatest torment for me is the almost incessant noise inside my head, which roars in my ears and sometimes escalates into a stormy clatter,” the composer wrote in a letter.

Like Smetana, around three million people in Germany today suffer from annoying noises in their ears that occur without any external stimuli: Tinnitus, or “ringing in the ears,” often manifests as a shrill whistling sound. Others hear a hissing, screeching, or constant buzzing. If this uninvited acoustic guest stays for more than three months, it is no longer referred to as acute tinnitus, but chronic tinnitus. For many sufferers, the noise in their ears has a massive impact on their body and mind. It can lead to depression, sleep disorders, reduced concentration, or psychological stress. Conversely, stress, for example due to overwork, can also trigger or exacerbate the noise.

Is it caused by changes in the auditory cortex?

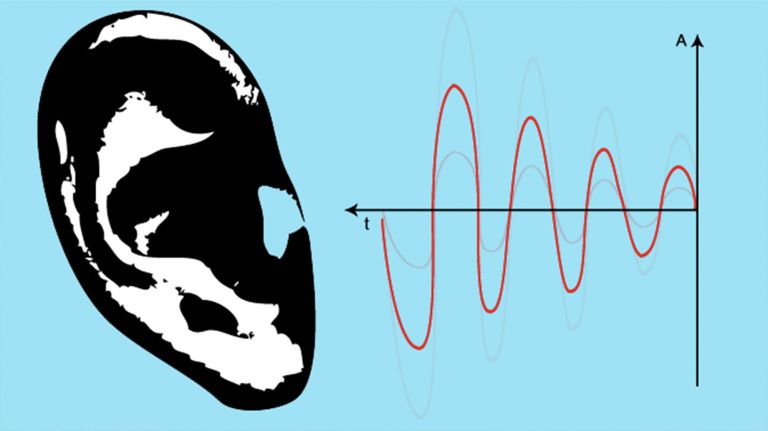

Tinnitus usually begins with a disturbance in the periphery. This can be acoustic trauma caused by a very loud noise or a foreign body in the ear canal Nevertheless, many researchers increasingly see the central nervous system as the actual cause. According to the widely accepted remapping theory, changes in the Auditory cortex could be responsible for tinnitus.

If excessive noise destroys Hair cells in the inner ear that are assigned to a specific frequency, the corresponding neurons in the auditory Cortex simply receive no or significantly less auditory input. This reduces their inhibitory effect on their neighbors, which represent adjacent frequencies. These frequencies then become overrepresented in the auditory cortex and now form the annoying noise in the ear without an external sound source. So much for the theory.

“However, it is still unclear whether brain reorganization is a causal prerequisite for tinnitus or rather an attempt at compensation,” says Berthold Langguth, former head of the Tinnitus Center at the University of Regensburg. The remapping theory assumes that the cortical response of the normal hearing field increases, causing the whistling sound. However, tinnitus usually occurs precisely in the spectrum that should actually be lost due to the destroyed hair cells, namely in the high-frequency range.

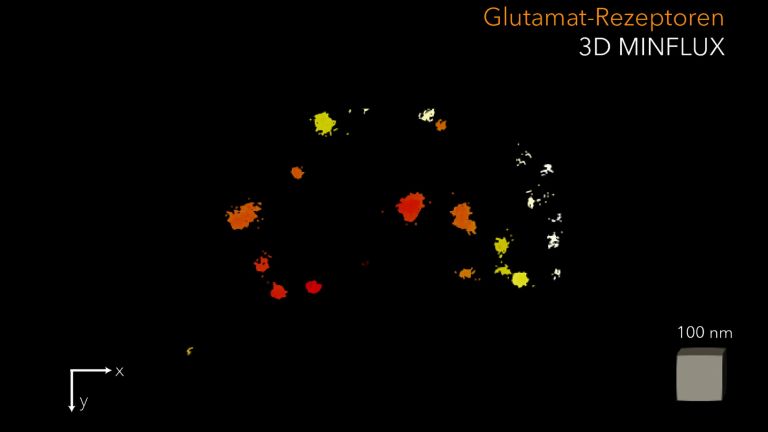

Alternative theory: Overstimulated nerve cells in the auditory cortex

A study by neuroscientists led by Sungchil Yang and Shaowen Bao from the University of California Berkeley in 2011 further highlighted this contradiction. The researchers examined rats suffering from tinnitus and found that inhibitory synaptic transmission in the rodents' auditory cortex was reduced, specifically in the areas that no longer received auditory input. This made the corresponding neurons more easily excitable – maybe a strategy to keep the level of neural activity constant and prevent inactivity despite the lack of input. When the researchers increased the level of the inhibitory Neurotransmitter GABA in their animal subjects by administering medication, they could no longer detect tinnitus – completely independently of the reorganization in the auditory cortex.

ear

auris

The ear is not only the organ of hearing, but also of balance. A distinction is made between the outer ear with the auricle and external auditory canal, the middle ear with the eardrum and ossicles, and the actual hearing and balance organ, the inner ear with the cochlea and semicircular canals.

ear canal

meatus acusticus externus

Sound waves captured by the outer ear enter the external auditory canal and cause the eardrum at the end of the canal to vibrate.

Auditory cortex

The auditory cortex is a part of the temporal lobe that is involved in processing acoustic signals. It is divided into the primary and secondary auditory cortex.

Hair cells

Sensory cells in the inner ear located in the organ of Corti and the semicircular canals. The hair cells in the organ of Corti are responsible for transducing (converting) the vibrations into electrical potentials. Each of these sensory cells has hair-like protrusions of varying lengths, called stereocilia. These are interconnected. The movement of these stereocilia caused by the vibrations is the key to signal transduction in the hair cells.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Neurotransmitter

A neurotransmitter is a chemical messenger, an intermediary substance. It is released by the sender neuron at the sites of cell-cell communication and has an excitatory or inhibitory effect on the receiver neuron.

GABA

GABA is an amino acid and the most important inhibitory neurotransmitter, which acts as a messenger in the transmission of information between neurons at their synapses.

Alternative theory: Overstimulated nerve cells in the auditory cortex

A study by neuroscientists led by Sungchil Yang and Shaowen Bao from the University of California Berkeley in 2011 further highlighted this contradiction. The researchers examined rats suffering from tinnitus and found that inhibitory synaptic transmission in the rodents' Auditory cortex was reduced, specifically in the areas that no longer received auditory input. This made the corresponding neurons more easily excitable – maybe a strategy to keep the level of neural activity constant and prevent inactivity despite the lack of input. When the researchers increased the level of the inhibitory Neurotransmitter GABA in their animal subjects by administering medication, they could no longer detect tinnitus – completely independently of the reorganization in the auditory cortex.

Instead of the reorganization processes, the increased excitability of neurons that have become unemployed could therefore be the trigger for the ringing in the ears. “This would be consistent with the clinical experience that tinnitus is perceived precisely in the frequency range where the greatest hearing loss occurs,” says Langguth.

Auditory cortex

The auditory cortex is a part of the temporal lobe that is involved in processing acoustic signals. It is divided into the primary and secondary auditory cortex.

Neurotransmitter

A neurotransmitter is a chemical messenger, an intermediary substance. It is released by the sender neuron at the sites of cell-cell communication and has an excitatory or inhibitory effect on the receiver neuron.

GABA

GABA is an amino acid and the most important inhibitory neurotransmitter, which acts as a messenger in the transmission of information between neurons at their synapses.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Brain areas beyond the auditory cortex also appear to be involved

Other researchers, such as neurophysiologist Josef Rauschecker from Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington, D.C., consider a remodeled Auditory cortex to be a necessary condition for tinnitus, but by no means a sufficient one. “After all, only 20 to 40 percent of people with noise-induced hearing loss develop the annoying ringing,” he says. “A model developed by my research group therefore attributes an equally decisive role to the limbic system.”

According to Rauschecker and his colleagues, the medial prefrontal cortex in particular – which some scientists consider part of the extended Limbic system – is normally able to suppress tinnitus signals from the auditory Cortex. However, as the researchers were able to show using imaging techniques, the volume of this brain region is reduced in tinnitus patients. Put simply, the switch for noise suppression in the limbic system is obviously not working properly.

The approach taken by Rauschecker's team answers some open questions. “However, I don't think it is suitable for explaining all the different forms of tinnitus,” says Berthold Langguth. He and his colleagues suspect that several networks in the brain contribute to ringing in the ears. “With our model, we want to take into account the clinical experience that tinnitus is extremely diverse.” Different networks in the brain are simultaneously active in the various “types” of tinnitus patients.

Those affected only consciously perceive the overstimulation of the auditory system when it is associated with activity in attention networks in the frontal and parietal areas. According to Langguth, the so-called salience network – which includes the Anterior cingulate cortex – encodes the significance of the tinnitus signal. “This network may also be the reason why tinnitus patients differ in their ability to block out the noise in their ears,” he says. “If it is activated, the subjective significance of the tinnitus is high, and it is difficult or even impossible to distract from it.”

The limbic system, which includes the amygdala, then provides the emotionally negative coloring. “We also attribute a decisive role to the Memory network around the Hippocampus – especially in chronic tinnitus.” Langguth's working group assumes a kind of tinnitus memory. Since there is no new input in the frequency range of the destroyed hair cells, the memory trace can no longer be overwritten by the disturbing noise. “This is how we explain the persistence of tinnitus perception.”

Auditory cortex

The auditory cortex is a part of the temporal lobe that is involved in processing acoustic signals. It is divided into the primary and secondary auditory cortex.

medial

A positional term – medial means "towards the middle." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction toward the body, away from the sides.

prefrontal cortex

Prefrontal cortex

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) forms the front part of the frontal lobe and is one of the brain's most important integration and control centers. It receives highly processed information from many other areas of the cortex and is responsible for planning, controlling, and flexibly adapting one's own behavior. Its central tasks include executive functions, working memory, emotion regulation, and decision-making. In addition, the PFC plays an important role in the cognitive evaluation and modulation of pain.

Limbic system

The limbic system is a functional unit in the brain. It consists of interconnected structures, primarily in the cerebrum and diencephalon. The structures assigned to the system vary depending on the source, but the most important components are the hippocampus, amygdala, cingulate gyrus, septum, and mammillary bodies. The limbic system is involved in autonomic and visceral processes as well as in mechanisms of emotion, memory, and learning. Some authors mistakenly reduce the limbic system to the emotional world by referring to it as the "emotional brain."

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

attention

Attention

Attention serves as a tool for consciously perceiving internal and external stimuli. We achieve this by focusing our mental resources on a limited number of stimuli or pieces of information. While some stimuli automatically attract our attention, we can select others in a controlled manner. The brain also unconsciously processes stimuli that are not currently the focus of our attention.

frontal

An anatomical position designation – frontal means "towards the forehead," i.e., at the front.

Anterior cingulate cortex

Anterior cingulate cortex/Anterior cingulate cortex/anterior cingulate cortex

Like the entire cingulate cortex, the anterior region of the limbic system regulates drive-controlled behavior. In the perception of pain, it is particularly associated with the affective pain component - including social pain as experienced through exclusion.

Memory

Memory is a generic term for all types of information storage in the organism. In addition to pure retention, this also includes the absorption of information, its organization, and retrieval.

Hippocampus

The hippocampus is the largest part of the archicortex and an area in the temporal lobe. It is also an important part of the limbic system. Functionally, it is involved in memory processes, but also in spatial orientation and learning. It comprises the subiculum, the dentate gyrus, and the Ammon's horn with its four fields CA1-CA4.

Changes in the structure of the hippocampus due to stress are associated with chronic pain. The hippocampus also plays an important role in the amplification of pain through anxiety.

Recommended articles

Re-learning is the order of the day

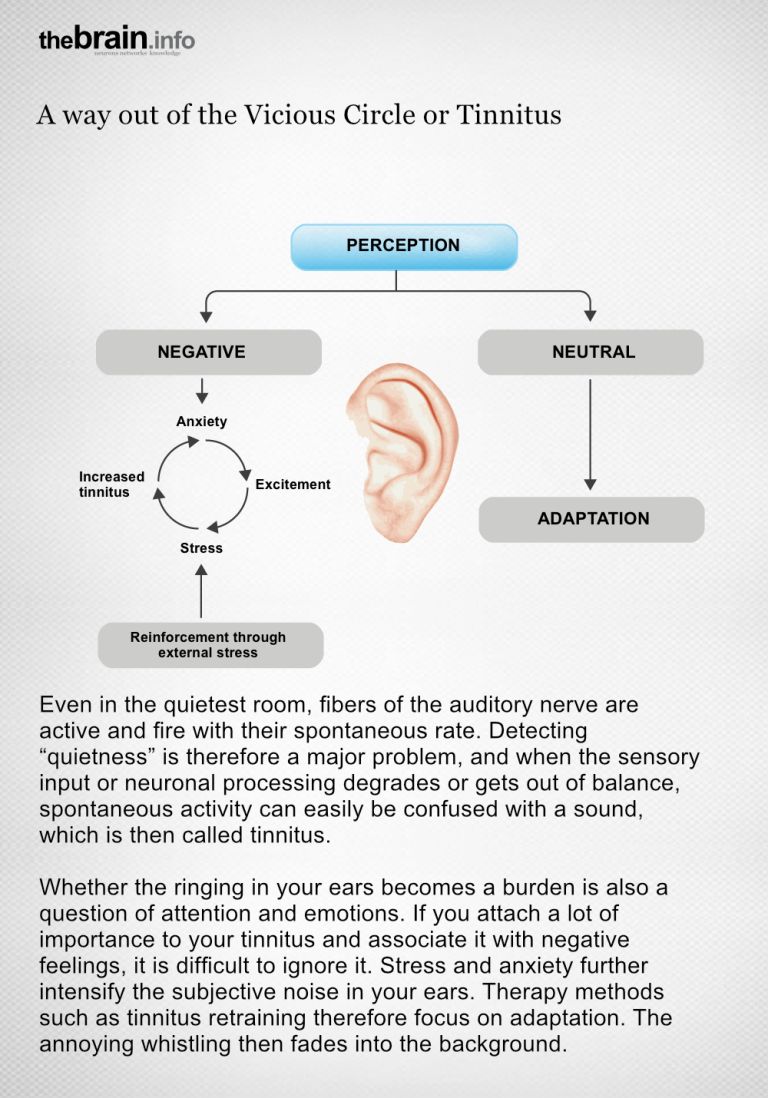

Since at least chronic tinnitus is considered incurable and drug treatments are controversial, some therapies focus on the subjective Perception of the annoying ringing. Tinnitus retraining, for example, is a treatment based on several components that includes hearing therapy as well as education and counseling about the condition and psychological support. “As far as can be measured, tinnitus is not actually a loud noise,” says physician Birgit Mazurek from the Tinnitus Center at Berlin's Charité hospital, who offers this treatment to her patients herself. Nevertheless, many sufferers perceive the noises in their ears as particularly loud. “This subjective perception is quite obviously the result of a negative learning process, in the course of which the perception of tinnitus becomes increasingly prominent.”

Perception

The term describes the complex process of gathering and processing information from stimuli in the environment and from the internal states of a living being. The brain combines the information, which is perceived partly consciously and partly unconsciously, into a subjectively meaningful overall impression. If the data it receives from the sensory organs is insufficient for this, it supplements it with empirical values. This can lead to misinterpretations and explains why we succumb to optical illusions or fall for magic tricks.

Habituation instead of cure

Tinnitus retraining is ultimately aimed at patients for whom the ringing is a real burden. A process of relearning is intended to reduce or eliminate the Perception of the noise in the ear. The aim is for those affected to become accustomed to the tinnitus and to manage it in their everyday lives. “Retraining is about improving quality of life – it does not promise a cure,” emphasizes Mazurek. “After all, the cause of tinnitus often cannot be determined.” Furthermore, damage to the peripheral and central structures cannot be reversed. “For example, it is not possible to form new hearing cells.” Pharmacological intervention, on the other hand, carries a very high risk of side effects such as speech disorders.

Retraining is a long-term process. “After about six months, the degree of stress is reduced, and it can decrease even further after that,” says Birgit Mazurek. Patients feel better not only in terms of their tinnitus, but also psychologically. And even if there is no real cure for chronic tinnitus yet, therapies can at least help patients come to terms with their uninvited guest.

Perception

The term describes the complex process of gathering and processing information from stimuli in the environment and from the internal states of a living being. The brain combines the information, which is perceived partly consciously and partly unconsciously, into a subjectively meaningful overall impression. If the data it receives from the sensory organs is insufficient for this, it supplements it with empirical values. This can lead to misinterpretations and explains why we succumb to optical illusions or fall for magic tricks.

ear

auris

The ear is not only the organ of hearing, but also of balance. A distinction is made between the outer ear with the auricle and external auditory canal, the middle ear with the eardrum and ossicles, and the actual hearing and balance organ, the inner ear with the cochlea and semicircular canals.

Publication: July 27, 2012

Update: December 18, 2016