A Labyrinth for Balance

Without it, we would be constantly spinning around: our sense of balance guides our body through space like a three-dimensional navigation device. Its control center is located deep in our ear and signals to our muscles and joints: maintain your posture!

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Hans Straka, Prof. Dr. Michael Pecka

Published: 17.10.2025

Difficulty: serious

- The Vestibular system is important for perceiving the position and movement of our own body in space.

- Three Semicircular canals form the organ of rotation, while two vestibular sacs are responsible for linear changes in speed (acceleration).

- The vestibular system cooperates with the Visual system and the sensors in muscles, tendons, and joints: they are both the source and the recipient of information about the position of the body in space.

- The connection to the Eye muscles is particularly fast: the Vestibulo-ocular reflex enables a stable image despite body movement.

- Disorders of the vestibular system lead to symptoms similar to “seasickness”: mainly dizziness and nausea.

Vestibular system

Vestibular apparatus/Organon vestibulare/vestibular organ

The vestibular system is part of the inner ear. Its sensors are located in the semicircular canals. As part of the balance system, it detects circular movements (rotations), acceleration, and gravity.

Semicircular canals

The three semicircular canals per ear are interconnected, fluid-filled tubes that are positioned almost at right angles to each other and belong to the balance organ in the inner ear (vestibular apparatus). They serve to register angular accelerations, i.e., rotational movements of the head.

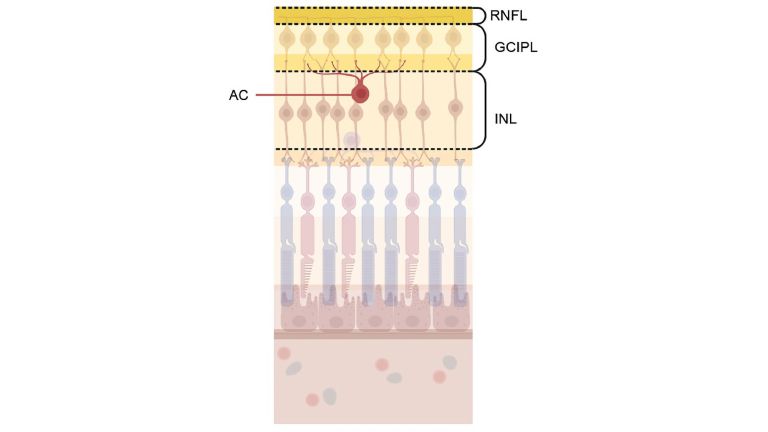

Visual system

The visual system is the part of the nervous system that processes visual information. It primarily comprises the eye, the optic nerve, the optic chiasm, the optic tract, the lateral geniculate nucleus, the optic radiation, the primary visual cortex, and the visual association cortices.

Eye

bulbus oculi

The eye is the sensory organ responsible for perceiving light stimuli – electromagnetic radiation within a specific frequency range. The light visible to humans lies in the range between 380 and 780 nanometers.

Vestibulo-ocular reflex

When we turn our head, our eyes automatically move in the opposite direction. This reflex ensures that a stable image is formed on the retina even when the head moves quickly. This is made possible by the connection between the semicircular canals of the vestibular system and the nerve nuclei of the eye muscles in the brain stem.

Children like to spin around as fast and for as long as possible. When they slow down, they often feel dizzy. This is because the endolymph in the inner ear – actually a sluggish fluid – eventually starts to move and spin along with the Semicircular canals during prolonged rotation. When the rotation ends abruptly, the endolymph continues to move for a short time. This gives the impression that the environment or oneself is suddenly spinning in the opposite direction – one becomes “seasick.”

ear

auris

The ear is not only the organ of hearing, but also of balance. A distinction is made between the outer ear with the auricle and external auditory canal, the middle ear with the eardrum and ossicles, and the actual hearing and balance organ, the inner ear with the cochlea and semicircular canals.

Semicircular canals

The three semicircular canals per ear are interconnected, fluid-filled tubes that are positioned almost at right angles to each other and belong to the balance organ in the inner ear (vestibular apparatus). They serve to register angular accelerations, i.e., rotational movements of the head.

The giant gondola swings back and forth in sweeping movements. It accelerates jerkily, brakes again, suddenly rears up into a loop and finally comes to a halt upside down at the highest point – for what seems like endless seconds. The passengers scream involuntarily. Blood rushes to their heads and the world around them begins to spin.

Anyone who has ever sat in the Break Dance, the Flying Fury, or a similar ride knows the feeling: fear mixed with happiness, your heart pounding, dizziness and nausea. When the machine finally comes to a stop, you stagger out of the gondola like a drunk. The world continues to spin a little longer, and your head and body have to find each other again. Adventures like this demand the utmost from your sense of balance. We usually only become aware of its existence when we put it to the test in this way. Normally, it does its job completely unobtrusively and with the utmost reliability.

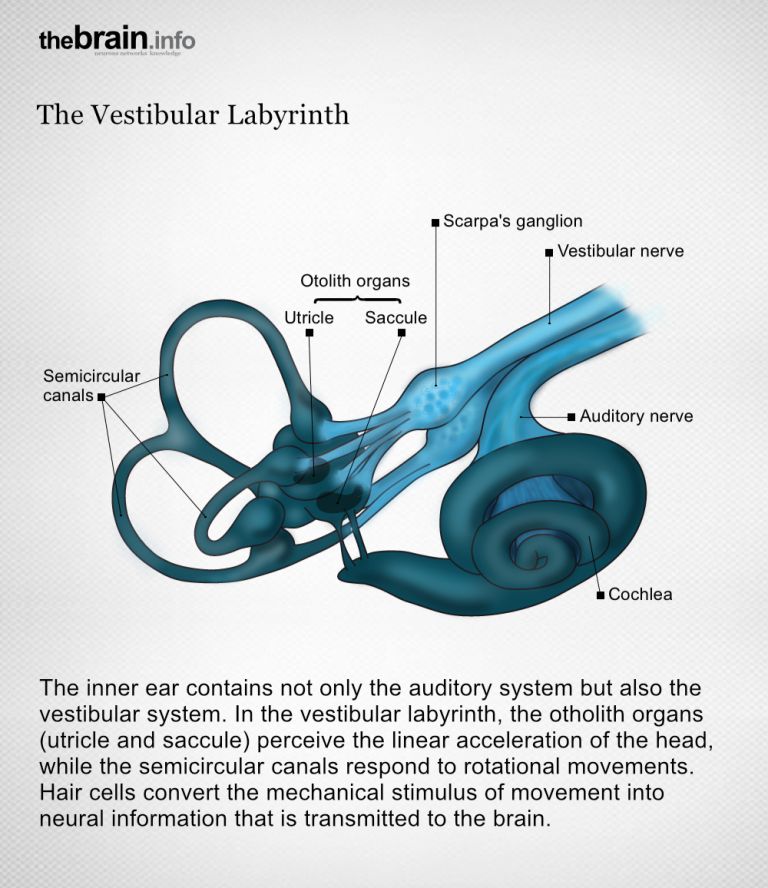

Sensitive in all directions

The center of the sense of balance, the vestibular system, is part of the ear and is therefore present on both sides of the head. It is located in the inner ear, a complex cavity. The vestibular apparatus itself has five components: three Semicircular canals and two vestibular sacs, known as the Macula organs. While the macula organs detect linear acceleration, such as when traveling in a car or elevator, the semicircular canals are responsible for rotational movements such as shaking or nodding the head.

ear

auris

The ear is not only the organ of hearing, but also of balance. A distinction is made between the outer ear with the auricle and external auditory canal, the middle ear with the eardrum and ossicles, and the actual hearing and balance organ, the inner ear with the cochlea and semicircular canals.

Semicircular canals

The three semicircular canals per ear are interconnected, fluid-filled tubes that are positioned almost at right angles to each other and belong to the balance organ in the inner ear (vestibular apparatus). They serve to register angular accelerations, i.e., rotational movements of the head.

Macula

macula lutea

The area of the retina with the highest density of photoreceptors. Due to this high "resolution," we see very sharply here. The diameter of the macula in humans is approximately 5 mm. The fovea centralis is located in the center of the macula.

Like three spirit levels in space

The three Semicircular canals are channels surrounded by membranes. Inside them is a fluid called endolymph. The canals are at 90-degree angles to each other: one is horizontal in the head, one runs perpendicular to it at an angle toward the front, and the third runs at an angle toward the back.

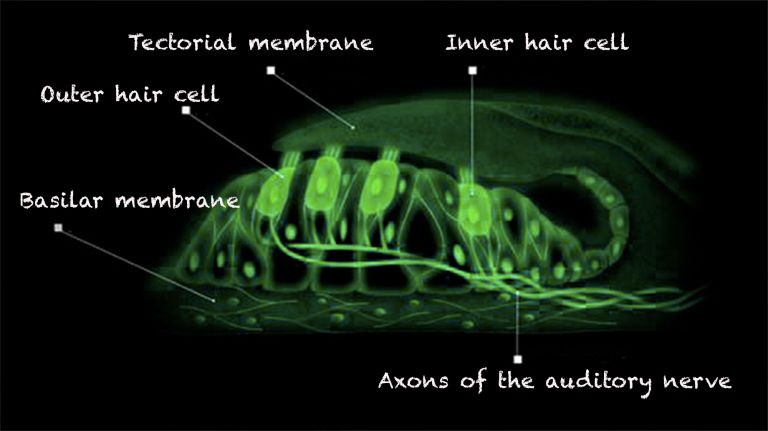

Each semicircular canal has a bulge called the ampulla. Embedded in a cushion inside the ampulla are Hair cells the sensory cells of the Vestibular system Each hair cell has numerous extensions that look like fine cilia. These cilia vary in length and protrude into a gelatinous membrane called the cupula, which is fused with the wall of the semicircular canal. The hair cells in an ampulla are all arranged in the same direction. As a result, they are excited or inhibited together.

When a person turns their head to the left, the wall of the semicircular canal also moves to the left. However, the endolymph inside is sluggish and does not flow immediately. “It's like a cup of coffee,” compares Stefan Glasauer from the Center for Somatosensory Research at the Department of Neurology at the University of Munich: If you place it on a turntable, the cup otates with it, but the coffee itself does not. The result is a relative movement of the coffee relative to the cup. In the case of the semicircular canals, this relative movement exerts pressure on the cupula and bends the cilia of the hair cells. For example, when you turn your head to the left, the cilia in the left horizontal semicircular canal bend to the right and are thus stimulated. In the opposite direction, they would be inhibited.

Semicircular canals

The three semicircular canals per ear are interconnected, fluid-filled tubes that are positioned almost at right angles to each other and belong to the balance organ in the inner ear (vestibular apparatus). They serve to register angular accelerations, i.e., rotational movements of the head.

Hair cells

Sensory cells in the inner ear located in the organ of Corti and the semicircular canals. The hair cells in the organ of Corti are responsible for transducing (converting) the vibrations into electrical potentials. Each of these sensory cells has hair-like protrusions of varying lengths, called stereocilia. These are interconnected. The movement of these stereocilia caused by the vibrations is the key to signal transduction in the hair cells.

Vestibular system

Vestibular apparatus/Organon vestibulare/vestibular organ

The vestibular system is part of the inner ear. Its sensors are located in the semicircular canals. As part of the balance system, it detects circular movements (rotations), acceleration, and gravity.

The macula organs – the otoliths indicate the vertical

Motion detection works slightly differently in the Macula organs. The small sacculus is located vertically in the skull and responds to corresponding accelerations, for example when traveling upward in an elevator. The large utriculus, on the other hand, reacts to horizontal acceleration forces, i.e., forward, backward, or even sideways movements. The sacs also contain Hair cells whose cilia protrude into a gelatinous mass: the otolith membrane.

This contains tiny calcium carbonate crystals, the otoliths, or colloquially known as ear stones. When a person is exposed to acceleration, for example when a bus driver steps on the gas, gravity and the weight of the otoliths cause the gelatinous mass to move, bending the fine cilia and stimulating the hair cells of the utricle.

Macula

macula lutea

The area of the retina with the highest density of photoreceptors. Due to this high "resolution," we see very sharply here. The diameter of the macula in humans is approximately 5 mm. The fovea centralis is located in the center of the macula.

Hair cells

Sensory cells in the inner ear located in the organ of Corti and the semicircular canals. The hair cells in the organ of Corti are responsible for transducing (converting) the vibrations into electrical potentials. Each of these sensory cells has hair-like protrusions of varying lengths, called stereocilia. These are interconnected. The movement of these stereocilia caused by the vibrations is the key to signal transduction in the hair cells.

ear

auris

The ear is not only the organ of hearing, but also of balance. A distinction is made between the outer ear with the auricle and external auditory canal, the middle ear with the eardrum and ossicles, and the actual hearing and balance organ, the inner ear with the cochlea and semicircular canals.

Teamwork with the eyes and depth perception

What happens after the sensory cells are stimulated is similar in the Macula organs and Semicircular canals the mechanical stimulus, i.e., the bending of the cilia, is translated into an electrical signal. Ion channels are located at the tips of the cilia, which protrude into the endolymphatic space. When the head is still, a small portion of these channels are open, so that the inflow and outflow of positively charged potassium ions from the endolymph into the Hair cells is balanced. Depending on the direction in which the cilia are bent, more ion channels open and more potassium ions flow into the cell: Depolarization occurs and the cell is stimulated. If, on the other hand, the ion channels are closed, fewer potassium ions flow in and hyperpolarization occurs, which has an inhibitory effect. The mechanical signal is thus translated into a neurochemical one.

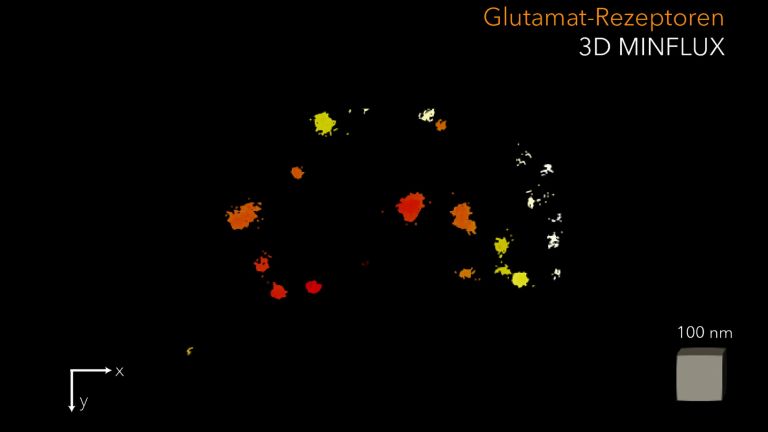

In the event of excitation, the hair cells release increased amounts of the Neurotransmitter Glutamate. This is how information about a specific body movement in space reaches the downstream nerve cell and is transmitted to the brain. The nerve fibers from the three semicircular canals and the two macula organs bundle together to form the vestibular nerve. In the inner ear, it joins the Auditory nerve to form the VIII Cranial nerve (nervus vestibulo-cochlearis). The fibers from the vestibular organs continue to the oldest part of the brain, the brain stem, where they contact nerve cells in the vestibular nuclei and in the Cerebellum. This is where all the information necessary for balance and Perception of one's own movement comes together: that from the macula organs and semicircular canals of both hemispheres of the brain. This is joined by signals from the eyes, which signal large-scale movements in the environment, as well as those from the proprioceptive sensory system, i.e., the receptors from muscles, tendons, and joints. The information from the various systems is linked together and forwarded to the eye, arm, and leg muscles.

Macula

macula lutea

The area of the retina with the highest density of photoreceptors. Due to this high "resolution," we see very sharply here. The diameter of the macula in humans is approximately 5 mm. The fovea centralis is located in the center of the macula.

Semicircular canals

The three semicircular canals per ear are interconnected, fluid-filled tubes that are positioned almost at right angles to each other and belong to the balance organ in the inner ear (vestibular apparatus). They serve to register angular accelerations, i.e., rotational movements of the head.

Hair cells

Sensory cells in the inner ear located in the organ of Corti and the semicircular canals. The hair cells in the organ of Corti are responsible for transducing (converting) the vibrations into electrical potentials. Each of these sensory cells has hair-like protrusions of varying lengths, called stereocilia. These are interconnected. The movement of these stereocilia caused by the vibrations is the key to signal transduction in the hair cells.

Depolarization

The decrease in membrane potential (towards 0 mV) from the resting potential, which is measured between the inside of the cell and the outside space and has a difference of -70 mV.

Neurotransmitter

A neurotransmitter is a chemical messenger, an intermediary substance. It is released by the sender neuron at the sites of cell-cell communication and has an excitatory or inhibitory effect on the receiver neuron.

Glutamate

Glutamate is an amino acid and the most important excitatory neurotransmitter, which acts as a messenger substance in the transmission of information between neurons at their synapses.

Auditory nerve

nervus cochlearis

The hair cells of the organ of Corti stimulate neurons in the spiral ganglion, which is located in the cavity of the cochlea. Their axons form the auditory nerve, which transmits electrical impulses from the inner ear to the brain. Together with the vestibular nerve (nervus vestibularis), the auditory nerve forms the VIII cranial nerve.

cranial

A positional term – cranial means "towards the head." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction along the neural axis, i.e., forward.

In animals (without upright gait), the designation is simpler, as it always means forward. Due to the upright gait of humans, the brain bends in relation to the spinal cord, where cranial also means "upward."

Cranial nerve

A group of 12 pairs of nerves that originate directly in the brain, mostly in the brain stem. They are numbered with Roman numerals (I–XII). Unlike the rest, the first and second cranial nerves (olfactory and optic nerves) are not part of the peripheral nervous system, but rather the central nervous system.

Cerebellum

Cerebellum

The cerebellum is an important part of the brain, located at the back of the brain stem and below the occipital lobe. It consists of two cerebellar hemispheres covered by the cerebellar cortex and plays an important role in motor processes, among other things. It develops from the rhombencephalon.

Perception

The term describes the complex process of gathering and processing information from stimuli in the environment and from the internal states of a living being. The brain combines the information, which is perceived partly consciously and partly unconsciously, into a subjectively meaningful overall impression. If the data it receives from the sensory organs is insufficient for this, it supplements it with empirical values. This can lead to misinterpretations and explains why we succumb to optical illusions or fall for magic tricks.

Recommended articles

A sharp image in seven milliseconds

The fastest connection is to the Cranial nerve nuclei that control the Eye muscles. The so-called “vestibulo-ocular reflex” takes only about seven milliseconds. It is one of the fastest reflexes in the central nervous system and enables us to see a stable image of our surroundings continuously while we move our head. Take jogging, for example: “Joggers should actually perceive their environment as a blurred photo,” explains sensorimotor researcher Glasauer. “Thanks to the vestibulo-ocular reflex, however, the eye compensates for the movement by moving in the opposite direction at the same speed.” If the head drops down, the eye moves up.

The motor neurons in the spinal cord, which ultimately control the muscles in the legs, are also informed of the change in position. They counteract this when, for example, we stumble, stand on a swaying ship, or the subway driver suddenly brakes, thus stabilizing our upright position. However, due to the large number of leg muscles, vestibulo-spinal reflexes are much less accurate than vestibulo-ocular reflexes. This is why we sometimes stumble.

Ultimately, the interaction of the vestibular, visual, and proprioceptive sensory systems enables us to perceive our body movements in space, orient ourselves visually, and maintain our balance even during complex movements such as gymnastics. The Vestibular system plays a crucial role in this. No matter which direction the head moves in, the Hair cells are so directionally sensitive that they specifically encode all movements and convert them into neural signals. This results in a pattern of excitation that the central nervous system can clearly interpret. It knows exactly where the head is in space and in which direction it is moving at any given moment. This system is therefore also an indispensable prerequisite for the functioning of our sense of orientation. Together with the Place cells and spatial cells, whose discovery was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2014 ▸ Sought and found: orientation cells, the vestibular system with its complex interconnections forms the GPS of the brain, so to speak.

cranial

A positional term – cranial means "towards the head." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction along the neural axis, i.e., forward.

In animals (without upright gait), the designation is simpler, as it always means forward. Due to the upright gait of humans, the brain bends in relation to the spinal cord, where cranial also means "upward."

Cranial nerve

A group of 12 pairs of nerves that originate directly in the brain, mostly in the brain stem. They are numbered with Roman numerals (I–XII). Unlike the rest, the first and second cranial nerves (olfactory and optic nerves) are not part of the peripheral nervous system, but rather the central nervous system.

Eye

bulbus oculi

The eye is the sensory organ responsible for perceiving light stimuli – electromagnetic radiation within a specific frequency range. The light visible to humans lies in the range between 380 and 780 nanometers.

Vestibular system

Vestibular apparatus/Organon vestibulare/vestibular organ

The vestibular system is part of the inner ear. Its sensors are located in the semicircular canals. As part of the balance system, it detects circular movements (rotations), acceleration, and gravity.

Hair cells

Sensory cells in the inner ear located in the organ of Corti and the semicircular canals. The hair cells in the organ of Corti are responsible for transducing (converting) the vibrations into electrical potentials. Each of these sensory cells has hair-like protrusions of varying lengths, called stereocilia. These are interconnected. The movement of these stereocilia caused by the vibrations is the key to signal transduction in the hair cells.

Place cells

Pyramidal cells in the hippocampus that encode a specific location in a specific environment – for example, a section of a maze. When a test animal is in the center of this area, the cell fires most strongly. Place cells were discovered in 1971 by John O'Keefe and Jonathon Dostrovsky.

Prone to disruption, but capable of rehabilitation

All these processes take place largely unconsciously in everyday life – unless the Perception of balance is disturbed. For example, sometimes the information from the different sensory sources does not match. This deception occurs at the train station, for example, when you are sitting in a stationary train and the train on the neighboring track starts to move. This creates a brief moment of uncertainty as to whether your own train or the other train is moving. In this case, the visual and vestibular systems in particular contradict each other: the eyes report movement, while the Vestibular system reports stillness.

In some people, however, the vestibular apparatus itself is disturbed – for example, due to circulatory disorders or inflammation in the inner ear. Those affected complain of vertigo, like after a ride on a carousel, and can no longer stand upright. “Such patients also report that they feel as if they are outside their bodies,” says Stefan Glasauer. Their awareness of the position and movement of their own body in space suffers.

Fortunately, however, the vestibular system is highly adaptable: if, for example, the inner ear is damaged in an accident and Hair cells are lost, the sense of balance initially functions poorly. “In the case of such permanent damage, the brain gets used to the deficit and can compensate for it with the remaining information in such a way that the patient's balance is permanently stabilized again,” explains Glasauer. However, compensating for such vestibular damage does not work as well in older people. Their sense of balance and the vestibulo-spinal reflexes that stabilize their posture are no longer as quick. This is one of the reasons why falls become more frequent with age.

Perception

The term describes the complex process of gathering and processing information from stimuli in the environment and from the internal states of a living being. The brain combines the information, which is perceived partly consciously and partly unconsciously, into a subjectively meaningful overall impression. If the data it receives from the sensory organs is insufficient for this, it supplements it with empirical values. This can lead to misinterpretations and explains why we succumb to optical illusions or fall for magic tricks.

Vestibular system

Vestibular apparatus/Organon vestibulare/vestibular organ

The vestibular system is part of the inner ear. Its sensors are located in the semicircular canals. As part of the balance system, it detects circular movements (rotations), acceleration, and gravity.

ear

auris

The ear is not only the organ of hearing, but also of balance. A distinction is made between the outer ear with the auricle and external auditory canal, the middle ear with the eardrum and ossicles, and the actual hearing and balance organ, the inner ear with the cochlea and semicircular canals.

Hair cells

Sensory cells in the inner ear located in the organ of Corti and the semicircular canals. The hair cells in the organ of Corti are responsible for transducing (converting) the vibrations into electrical potentials. Each of these sensory cells has hair-like protrusions of varying lengths, called stereocilia. These are interconnected. The movement of these stereocilia caused by the vibrations is the key to signal transduction in the hair cells.

First published on August 16, 2012

Last updated on October 17, 2025