Hearing – more than just Sound and Vibration

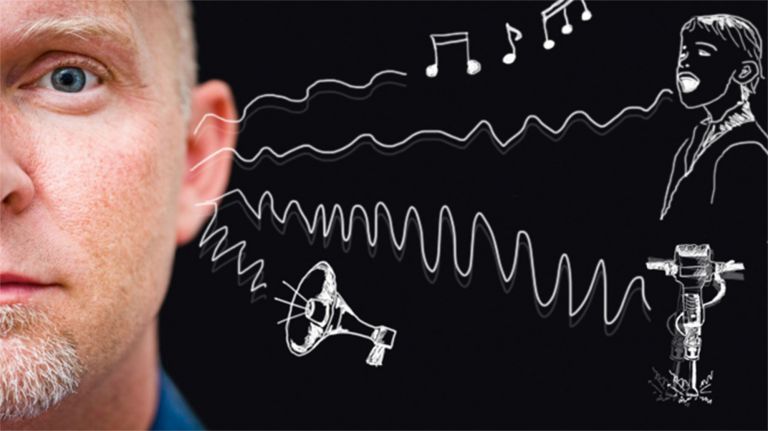

Hearing is our fastest sense and requires little input. The brain constructs a rich acoustic world from simple vibrations of the eardrums. It processes sounds, speech, and music differently.

Scientific support: Prof. Manfred Kössl, Prof. Dr. Michael Pecka

Published: 17.10.2025

Difficulty: easy

- The ear constructs the complex world of acoustics from minimal mechanical input.

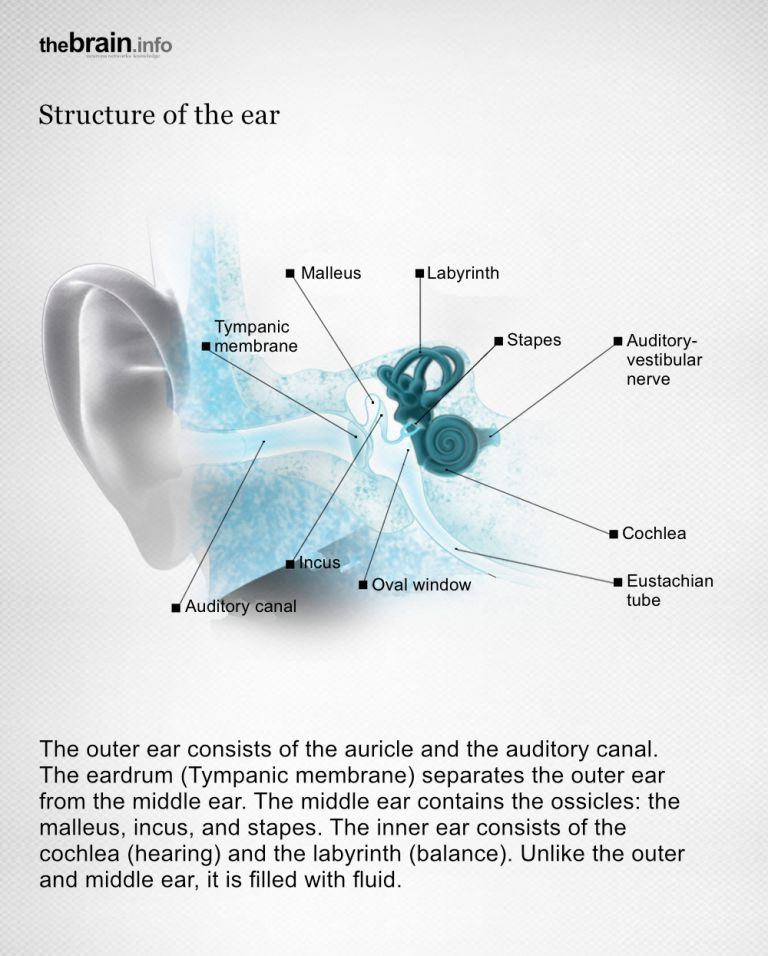

- The outer ear collects sound vibrations, which are transmitted from the outer ear to the Middle ear Sound waves deflect the eardrum at the end of the ear canal, which in turn causes the Ossicles to vibrate. The Cochlea in the inner ear converts this mechanical event into neural impulses, which then race along the Auditory pathway and ultimately reach the auditory cortex.

- Different groups of neurons process high and low frequencies, allowing us to distinguish between mere noises, music, and speech.

ear

auris

The ear is not only the organ of hearing, but also of balance. A distinction is made between the outer ear with the auricle and external auditory canal, the middle ear with the eardrum and ossicles, and the actual hearing and balance organ, the inner ear with the cochlea and semicircular canals.

Middle ear

auris media

The eardrum forms the boundary between the outer ear and the middle ear. The ossicles – the malleus, incus, and stapes – transmit the vibration of the eardrum to the inner ear via the oval window. The middle ear is filled with air.

Ossicles

The three bones located in the middle ear – the stapes, malleus, and incus – are known as the ossicles. These are the smallest bones in the human body. They mechanically transmit sound waves from the eardrum to the cochlea.

Cochlea

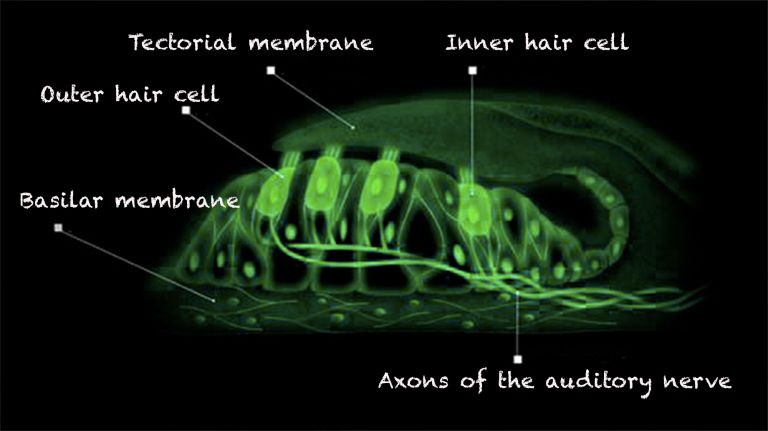

The cochlea is the part of the inner ear that contains the organ of Corti, which is responsible for converting acoustic signals into nerve impulses.

Auditory pathway

The auditory pathway refers to the nerve fibers that transmit acoustic information from the inner ear to the primary auditory cortex. In humans, the auditory pathway consists of five switching points: the spiral ganglion, the auditory nuclei in the brainstem, the inferior colliculus, the medial geniculate body of the thalamus, and the primary auditory cortex.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Imagine the following situation: On the shore of a lake, a child has dug two narrow channels from the water, about a meter long and a few centimeters wide. The waterways are about a meter apart, and a small boat floats on the surface of each, gently rocked by the waves of the lake. You are sitting in the middle between the channels and have a task: based solely on the swaying mini boats, you have to figure out what is going on on the lake, how many watercraft are on it, and where. Completely impossible, you might think. And yet you take it for granted that you can hear where individual speakers are in a room.

Both situations are quite comparable: when we hear, we only receive information from the eardrums in our left and right ears, which vibrate due to sound waves produced by human voices. From these vibrations, the brain is able to reconstruct a complex acoustic world. And hearing not only tells us where a sound source is located and whether it is, for example, a person or a busy road. The brain processes a wide variety of sound information, from the rustling of leaves to the voice of a loved one, and links it to experiences and emotions or even to other sensory impressions.

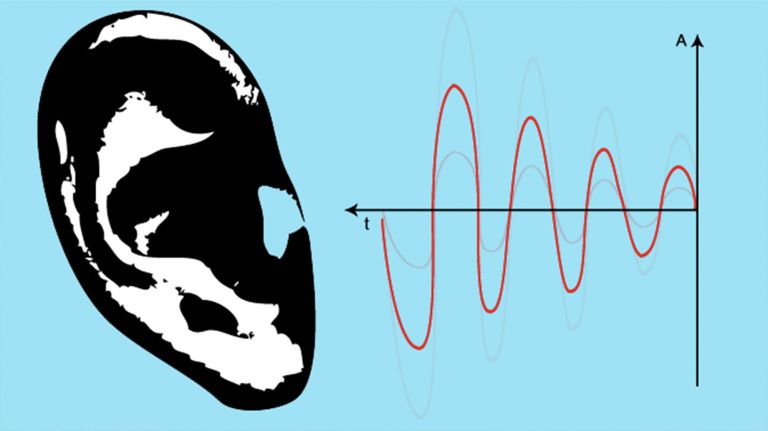

Physically speaking, sound itself is nothing more than fluctuations in air pressure. It's dead quiet in space because there are no pressure fluctuations in a vacuum – the spectacular loud explosions in science fiction movies are an invention of Hollywood. ▸ What do we actually hear? Depending on whether the sound travels in slow or fast waves, we perceive it as a low or high tone. The frequency, expressed in hertz (Hz), is the measure of the number of vibrations per second. The human ear can hear frequencies between 20 and 20,000 Hz. The cries of bats, for example, are usually too high-pitched for us to hear.

emotions

Neuroscientists understand "emotions" to be complex response patterns that include experiential, physiological, and behavioral components. They arise in response to personally relevant or significant events and generate a willingness to act, through which the individual attempts to deal with the situation. Emotions typically occur with subjective experience (feeling), but differ from pure feeling in that they involve conscious or implicit engagement with the environment. Emotions arise in the limbic system, among other places, which is a phylogenetically ancient part of the brain. Psychologist Paul Ekman has defined six cross-cultural basic emotions that are reflected in characteristic facial expressions: joy, anger, fear, surprise, sadness, and disgust.

ear

auris

The ear is not only the organ of hearing, but also of balance. A distinction is made between the outer ear with the auricle and external auditory canal, the middle ear with the eardrum and ossicles, and the actual hearing and balance organ, the inner ear with the cochlea and semicircular canals.

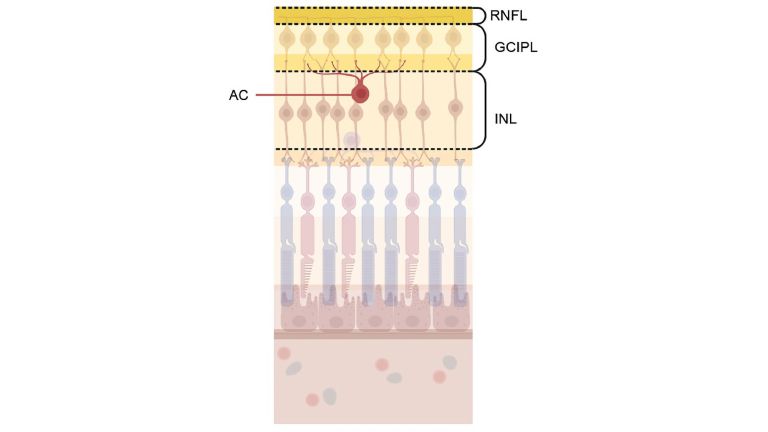

From the outer ear to the brain

The outer ear's pinna collects sound. It forms a kind of funnel and directs the vibrations into the ear canal, from where they reach the Middle ear The sound waves hit the eardrum at the end of the ear canal and deflect it, causing the three Ossicles to vibrate. The Cochlea in the inner ear finally converts the mechanical input into neural impulses, which then race along the Auditory pathway ▸ From Wiggling to the wonderful Variety of Sounds The signal is transmitted in this way to various nuclei in the brain stem, a kind of distribution station from which parallel signaling pathways run. Near the end of the auditory pathway, the thalamus projects the information to the Primary auditory cortex in the Temporal lobe It is mainly thanks to this “auditory center” that we are able to consciously perceive the acoustic diversity of the world.

But what makes the small but crucial difference between whether the neurons in our heads are processing a Beatles song or our partner's oath of love? Different groups of neurons in the Auditory cortex respond to different frequencies. ▸ From Sound to Word And sounds each have their own characteristic frequency spectrum. Human speech, for example, ranges from 80 Hz to 12 kHz. And while music or background noise is a mixture of different frequencies, each voice has its own typical frequency. The auditory Cortex uses this to sort information: it distinguishes human words from other acoustic sources and forwards this information to other groups of neurons and areas of the brain, such as the roar of a jackhammer or the sound of a Beethoven sonata.

The example of music in particular shows how diversely our brain processes sounds. When we listen to a melody, the auditory cortex is only the entry point for the information. In addition, many other areas of the brain come into action to process experiences and associations. Which ones these are and to what extent varies from person to person. When we listen to a string quartet, for example, the brain also links the acoustic information with the visual image of violinists and cellists that we have stored in our memory, as well as with emotions and memories that we associate with the music. So, it's no wonder that music can send a pleasant shiver down your spine or bring tears to your eyes, or that teenagers freak out at a concert by their favorite band.

But hearing is not just for pleasure; it also has a very practical, sometimes vital, significance for humans and animals. Without hearing the crack of a branch caused by a nearby predator, many creatures would fare badly. And we also need to locate sound so that we don't literally get run over by a car. To do this, our hearing uses a trick: for high-pitched sounds, it evaluates the difference in intensity with which the sound reaches both ears. For low frequencies, it calculates the time difference it takes for the sound to reach the ear further away from the source of the stimulus.

ear

auris

The ear is not only the organ of hearing, but also of balance. A distinction is made between the outer ear with the auricle and external auditory canal, the middle ear with the eardrum and ossicles, and the actual hearing and balance organ, the inner ear with the cochlea and semicircular canals.

Middle ear

auris media

The eardrum forms the boundary between the outer ear and the middle ear. The ossicles – the malleus, incus, and stapes – transmit the vibration of the eardrum to the inner ear via the oval window. The middle ear is filled with air.

ear canal

meatus acusticus externus

Sound waves captured by the outer ear enter the external auditory canal and cause the eardrum at the end of the canal to vibrate.

Ossicles

The three bones located in the middle ear – the stapes, malleus, and incus – are known as the ossicles. These are the smallest bones in the human body. They mechanically transmit sound waves from the eardrum to the cochlea.

Cochlea

The cochlea is the part of the inner ear that contains the organ of Corti, which is responsible for converting acoustic signals into nerve impulses.

Auditory pathway

The auditory pathway refers to the nerve fibers that transmit acoustic information from the inner ear to the primary auditory cortex. In humans, the auditory pathway consists of five switching points: the spiral ganglion, the auditory nuclei in the brainstem, the inferior colliculus, the medial geniculate body of the thalamus, and the primary auditory cortex.

Primary auditory cortex

The first processing station in the cerebral cortex for auditory information. The primary auditory cortex is located in the Heschl's gyrus and receives inputs from the medial geniculate nucleus of the thalamus. It is organized tonotopically – its neurons are arranged continuously according to frequency.

Temporal lobe

Lobus temporalis

The temporal lobe is one of the four lobes of the cerebrum and is located laterally (on the side) at the bottom. It contains important areas such as the auditory cortex and parts of Wernicke's area, as well as areas for higher visual processing; deep within it lies the medial temporal lobe with structures such as the hippocampus.

Auditory cortex

The auditory cortex is a part of the temporal lobe that is involved in processing acoustic signals. It is divided into the primary and secondary auditory cortex.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

emotions

Neuroscientists understand "emotions" to be complex response patterns that include experiential, physiological, and behavioral components. They arise in response to personally relevant or significant events and generate a willingness to act, through which the individual attempts to deal with the situation. Emotions typically occur with subjective experience (feeling), but differ from pure feeling in that they involve conscious or implicit engagement with the environment. Emotions arise in the limbic system, among other places, which is a phylogenetically ancient part of the brain. Psychologist Paul Ekman has defined six cross-cultural basic emotions that are reflected in characteristic facial expressions: joy, anger, fear, surprise, sadness, and disgust.

Recommended articles

Life begins to listen

The ability to process sound, which is essential for survival, developed gradually over the course of evolution. Early creatures that inhabited the water and later also the land did not yet have hearing. They could only perceive sound in the form of vibrations in water or ground. The first jawless fish, for example, had a so-called lateral line organ in which Hair cells detected local water movements and helped the fish to orient themselves in the water. This developed into the inner ear of vertebrates with the Cochlea and the Vestibular system The latter is, as the name suggests, indispensable for maintaining balance in various situations in life. ▸ A Labyrinth for Balance In modern bony fish, part of the vestibular system has developed into the hearing organ. It contains the so-called auditory stones, fine calcium crystals that react to sound vibrations and transmit this information to the hair cells. ▸ Animal Hearing

At the same time as the development of hearing, the brains of the ancestors of mammals probably increased significantly in volume. After all, they now had to process far more impressions from the environment.

lateral

A positional term – lateral means "towards the side." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction at right angles to the neural axis, i.e., to the right or left.

Hair cells

Sensory cells in the inner ear located in the organ of Corti and the semicircular canals. The hair cells in the organ of Corti are responsible for transducing (converting) the vibrations into electrical potentials. Each of these sensory cells has hair-like protrusions of varying lengths, called stereocilia. These are interconnected. The movement of these stereocilia caused by the vibrations is the key to signal transduction in the hair cells.

ear

auris

The ear is not only the organ of hearing, but also of balance. A distinction is made between the outer ear with the auricle and external auditory canal, the middle ear with the eardrum and ossicles, and the actual hearing and balance organ, the inner ear with the cochlea and semicircular canals.

Cochlea

The cochlea is the part of the inner ear that contains the organ of Corti, which is responsible for converting acoustic signals into nerve impulses.

Vestibular system

Vestibular apparatus/Organon vestibulare/vestibular organ

The vestibular system is part of the inner ear. Its sensors are located in the semicircular canals. As part of the balance system, it detects circular movements (rotations), acceleration, and gravity.

Even fetuses prick up their ears

Today, hearing develops a little faster in new earthlings than it did during the evolutionary period. From around the 23rd week of pregnancy, the first reactions of the fetus to acoustic stimuli can be detected, including an increased pulse rate. In the last trimester of pregnancy, fetuses can hear – especially their mother's voice. No wonder they prefer its sound immediately after birth. Development is particularly rapid in the first year of life. While newborns are barely able to hear high frequencies, six-month-old infants can already perceive almost the entire acoustic spectrum of the human ear.

It is not only newborns who are not particularly receptive to high-pitched sounds, but often also people with tinnitus. ▸ Ringing in the Ears Instead of coming from outside, these agonizing noises come from within – and in most cases they are not even objectively perceptible. Tinnitus often originates from damage to the inner ear, for example due to acoustic trauma. However, as more and more scientists believe, it is not the ear itself that is responsible for the persistent, nerve-wracking whistling, but rather the brain.

Excessive or prolonged noise can not only trigger tinnitus, but also damage mental and physical health in other ways ▸ Full Blast on the Ears. So, it makes perfect sense to take care of your hearing. As long as it functions properly, it does an amazing amount with the input of simple air pressure fluctuations – and enriches our sensory experience with the fantastic diversity of sound.

ear

auris

The ear is not only the organ of hearing, but also of balance. A distinction is made between the outer ear with the auricle and external auditory canal, the middle ear with the eardrum and ossicles, and the actual hearing and balance organ, the inner ear with the cochlea and semicircular canals.

First published on July 27, 2012

Last updated on October 17, 2025