From wiggling to the wonderful variety of sounds

When we think of hearing, the outer ear is the first thing that comes to mind. However, other factors are essential for us to interpret sound as chirping, rustling, or murmuring, such as the anatomy of the cochlea and the computing power of the auditory pathway in the brain.

Scientific support: Prof. Manfred Kössl, Prof. Dr. Werner Hemmert

Published: 17.10.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

- Sound information is transmitted mechanically from the outer ear to the inner ear.

- At the first station of the auditory pathway, in the cochlea, mechanical information is converted into electrical nerve impulses.

- The neural signal from the inner ear is transmitted to various nuclei in the brainstem.

- The output of the nuclei is transmitted via the Midbrain (specifically via the inferior colliculi) to a switching station of the thalamus, the medial geniculate nucleus.

- The medial geniculate nucleus projects to the Primary auditory cortex in the temporal lobe.

ear

auris

The ear is not only the organ of hearing, but also of balance. A distinction is made between the outer ear with the auricle and external auditory canal, the middle ear with the eardrum and ossicles, and the actual hearing and balance organ, the inner ear with the cochlea and semicircular canals.

Midbrain

mecencephalon

The midbrain is the uppermost section of the brain stem. Its regions are located around the aqueduct, a canal filled with cerebrospinal fluid. Prominent structures include the tectum, tegmentum, and substantia nigra.

inferior

An anatomical position designation – inferior means located further down, the lower part.

medial

A positional term – medial means "towards the middle." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction toward the body, away from the sides.

Nucleus

In cell biology, the nucleus in a cell is the cell nucleus, which contains the chromosomes, among other things. In neuroanatomy, the nucleus in the nervous system refers to a collection of cell bodies – known as gray matter in the central nervous system and ganglia in the peripheral nervous system.

Primary auditory cortex

The first processing station in the cerebral cortex for auditory information. The primary auditory cortex is located in the Heschl's gyrus and receives inputs from the medial geniculate nucleus of the thalamus. It is organized tonotopically – its neurons are arranged continuously according to frequency.

As early as 1971, neurophysiologist Jerzy Rose and his colleagues at the University of Wisconsin measured the electrical activity of individual spiral Ganglion cells in the Auditory nerve They discovered that each cell responds to soundwaves of a specific frequency. Later studies have shown that this frequency specificity extends throughout the entire Auditory pathway Not only the Hair cells of the cochlea, but also many nerve cells of the Auditory cortex are sensitive to a specific pitch. Researchers refer to this as the characteristic frequency of a Neuron. On the surface of the auditory cortex, the different pitches can be assigned to specific areas. Researchers summarize this spatial division of frequency ranges in the brain with the term “tonotopy.”

Ganglion

Term for a cluster of nerve cell bodies in the peripheral nervous system. The term nerve node is often used because of its appearance. (Greek gágglion = knot-like)

Auditory nerve

nervus cochlearis

The hair cells of the organ of Corti stimulate neurons in the spiral ganglion, which is located in the cavity of the cochlea. Their axons form the auditory nerve, which transmits electrical impulses from the inner ear to the brain. Together with the vestibular nerve (nervus vestibularis), the auditory nerve forms the VIII cranial nerve.

Auditory pathway

The auditory pathway refers to the nerve fibers that transmit acoustic information from the inner ear to the primary auditory cortex. In humans, the auditory pathway consists of five switching points: the spiral ganglion, the auditory nuclei in the brainstem, the inferior colliculus, the medial geniculate body of the thalamus, and the primary auditory cortex.

Hair cells

Sensory cells in the inner ear located in the organ of Corti and the semicircular canals. The hair cells in the organ of Corti are responsible for transducing (converting) the vibrations into electrical potentials. Each of these sensory cells has hair-like protrusions of varying lengths, called stereocilia. These are interconnected. The movement of these stereocilia caused by the vibrations is the key to signal transduction in the hair cells.

Auditory cortex

The auditory cortex is a part of the temporal lobe that is involved in processing acoustic signals. It is divided into the primary and secondary auditory cortex.

Neuron

A neuron is a specialized cell in the nervous system that is responsible for processing and transmitting information. It receives signals via its dendrites and transmits them via its axon. Transmission occurs electrically within the neuron and, between neurons, usually chemically via synapses.

In the beginning, it's just a wiggle: sound waves cause the eardrum to vibrate. But how does this become the fascinating world of sounds, the birdsong in the morning, the delicate strumming of a violin? A lot of computing power is required at numerous points along the auditory pathway.

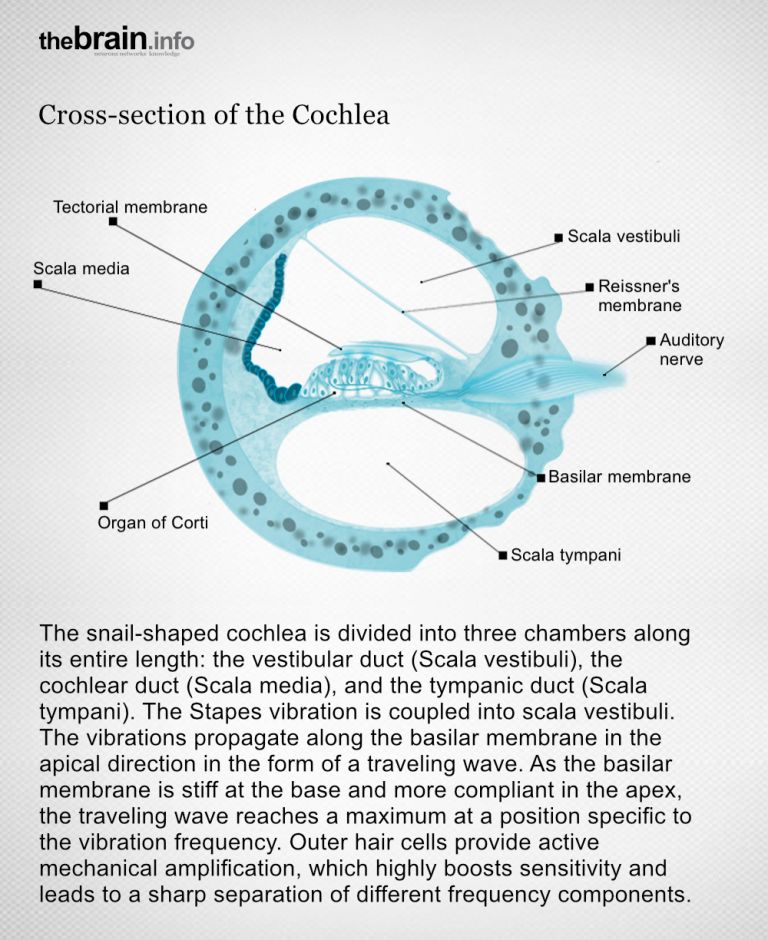

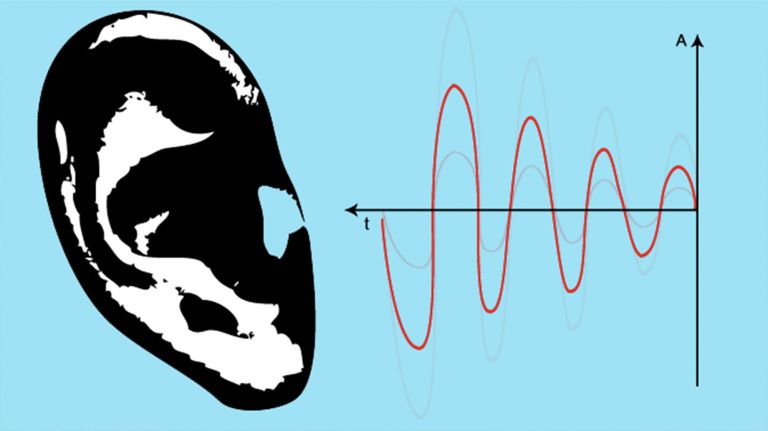

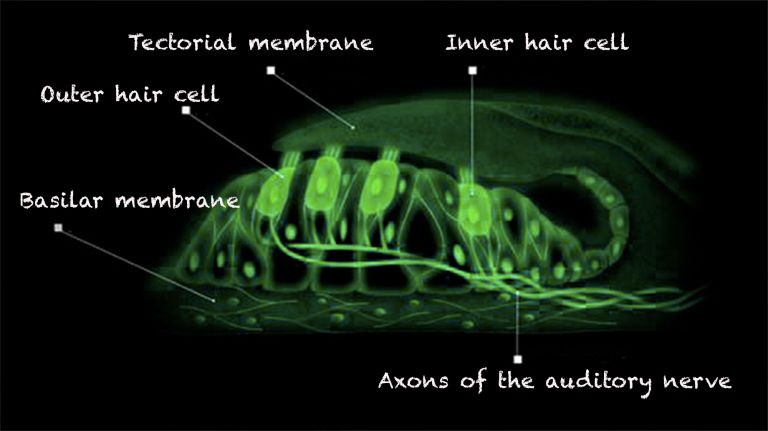

First, the sound is processed mechanically. The eardrum vibrates, and these movements are transmitted by the Ossicles of the Middle ear – the malleus, incus, and stapes – to a membrane called the oval window. Behind it lies the inner ear with the Cochlea. There, the basilar membrane, a tissue structure that runs the entire length of the cochlea, picks up the vibration. This Basilar membrane is narrow and stiff at the beginning but becomes wider and more flexible. In conjunction with the spiral-shaped and tapering anatomy of the cochlea, this ensures that each section of the basilar membrane is only set into vibration by a specific frequency range of sound. High-pitched sounds set the membrane at the beginning of the cochlea in motion, while low-pitched sounds only do so a few cochlear turns later.

Ossicles

The three bones located in the middle ear – the stapes, malleus, and incus – are known as the ossicles. These are the smallest bones in the human body. They mechanically transmit sound waves from the eardrum to the cochlea.

Middle ear

auris media

The eardrum forms the boundary between the outer ear and the middle ear. The ossicles – the malleus, incus, and stapes – transmit the vibration of the eardrum to the inner ear via the oval window. The middle ear is filled with air.

ear

auris

The ear is not only the organ of hearing, but also of balance. A distinction is made between the outer ear with the auricle and external auditory canal, the middle ear with the eardrum and ossicles, and the actual hearing and balance organ, the inner ear with the cochlea and semicircular canals.

Cochlea

The cochlea is the part of the inner ear that contains the organ of Corti, which is responsible for converting acoustic signals into nerve impulses.

Basilar membrane

The basilar membrane runs through the cochlea for a length of approximately 34 mm. It is stretched like the string of a violin, narrow and stiff at the base and wider and more flexible at the apex. Incoming sound frequencies cause it to vibrate. This movement is picked up by the hair cells in the organ of Corti and converted into nerve impulses.

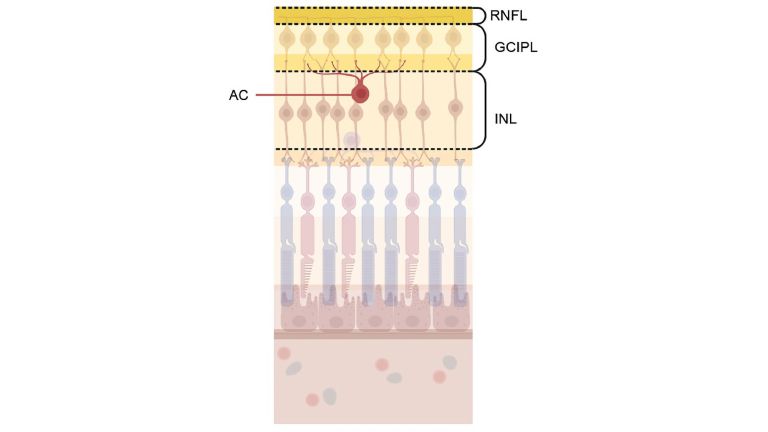

Analog-to-digital conversion: mechanical information becomes electrical

The Basilar membrane is covered by the so-called organ of Corti, which contains the inner Hair cells that convert the analog sound-induced vibrations into nerve impulses. Only then does the auditory information become accessible for data processing in the brain. Essential for the conversion, or transduction, of physical stimuli into electrical impulses is a specific type of sensory cell in the organ of Corti: the auditory cells. These cells have around a hundred hair-like projections at their tips, the stereocilia,which is why they are also called hair cells. When an area of the basilar membrane vibrates, the hairs of the auditory cells at that point are stimulated. This is the crucial movement, because it opens special ion channels in the cell membrane, the transduction channels.

Basilar membrane

The basilar membrane runs through the cochlea for a length of approximately 34 mm. It is stretched like the string of a violin, narrow and stiff at the base and wider and more flexible at the apex. Incoming sound frequencies cause it to vibrate. This movement is picked up by the hair cells in the organ of Corti and converted into nerve impulses.

Hair cells

Sensory cells in the inner ear located in the organ of Corti and the semicircular canals. The hair cells in the organ of Corti are responsible for transducing (converting) the vibrations into electrical potentials. Each of these sensory cells has hair-like protrusions of varying lengths, called stereocilia. These are interconnected. The movement of these stereocilia caused by the vibrations is the key to signal transduction in the hair cells.

Excitation in the hair cell

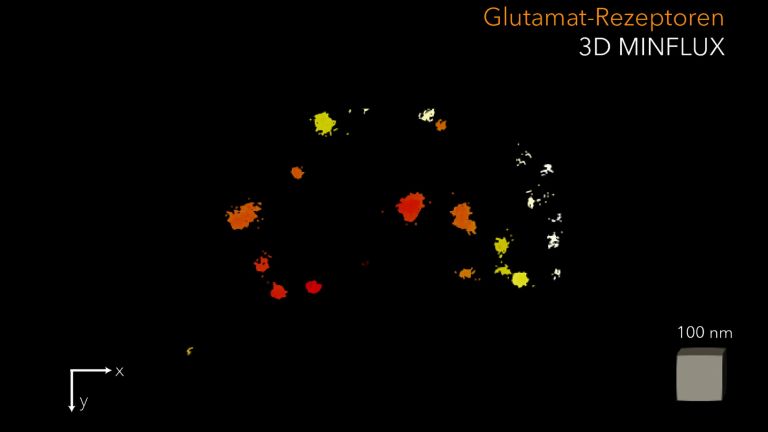

As soon as the transduction channels open, positively charged potassium ions flow into the interior of the hair cell, causing a change in charge. Each hair cell is connected via a Synapse to a spiral Ganglion cell, whose extensions form the auditory nerve, the nervus cochlearis. Only when this very specific hair cell is stimulated according to its frequency is the corresponding nerve cell in the spiral ganglion excited – and only then does it fire its action potentials.

Synapse

A synapse is a connection between two neurons and serves as a means of communication between them. It consists of a presynaptic region – the terminal button of the sender neuron – and a postsynaptic region – the region of the receiver neuron with its receptors. Between them lies the synaptic cleft.

Ganglion

Term for a cluster of nerve cell bodies in the peripheral nervous system. The term nerve node is often used because of its appearance. (Greek gágglion = knot-like)

Recommended articles

Parallel pathways of the auditory pathway to the brain

This signal is transmitted to various areas in the Brain stem the fibers of the Auditory nerve lead via the vestibulocochlear nerve to the two auditory nuclei, the ventral cochlear Nucleus and the dorsal cochlear nucleus. These nuclei form a kind of distribution station from which numerous parallel signal pathways originate.

To keep things simple, we will follow just one, but very important, pathway on its way to the Auditory cortex in the brain: the cells in the ventral cochlear nucleus send input to the so-called superior olive nucleus on both sides of the brain stem,which is actually a complex of several nuclei. The nerve network there reacts sensitively to time differences: if a sound reaches the left ear fractions of a second earlier than the right ear, the sound source is very likely to be to the left of the head. The upper olive is therefore involved in sound localization. From there, fibers also return to the inner ear. This feedback can influence the sensitivity of hearing.

Let us now continue to follow the Auditory pathway towards the auditory Cortex: from the olive complex, impulses travel via a lateral loop pathway (Latin: lemniscus lateralis) to a specific location in the Midbrain. The “lower colliculi” located there, the colliculi inferiores, are important for attention processes. They also help to control the movement of the head towards a specific stimulus.

The colliculi inferiores send the auditory information to the thalamus, which is considered the “gateway to the cortex.” The medial geniculate nucleus (CGM) is responsible for auditory signals there. Since the thalamus receives input from both sides, each Hemisphere of the brain receives information from both ears. The extensions of the neurons in the CGM form the auditory radiation, which transmits the information to the Primary auditory cortex in the Temporal lobe Speech is then analyzed in the secondary areas of the auditory cortex (Wernicke's area). This area, also known as the auditory center, processes acoustic signals. Ultimately, it is mainly thanks to this area that we are able to consciously perceive the voice of a loved one or the rustling of leaves.

Brain stem

truncus cerebri

The "trunk" of the brain, to which all other brain structures are "attached," so to speak. From bottom to top, it comprises the medulla oblongata, the pons, and the mesencephalon. It transitions into the spinal cord below. It is a center for vital functions such as breathing and heartbeat and contains ascending and descending pathways between the cerebrum, cerebellum, and spinal cord.

Auditory nerve

nervus cochlearis

The hair cells of the organ of Corti stimulate neurons in the spiral ganglion, which is located in the cavity of the cochlea. Their axons form the auditory nerve, which transmits electrical impulses from the inner ear to the brain. Together with the vestibular nerve (nervus vestibularis), the auditory nerve forms the VIII cranial nerve.

ventral

A positional term – ventral means "towards the abdomen." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction perpendicular to the neural axis, i.e., downwards or forwards.

In animals (that do not walk upright), the term is simpler, as it always means toward the abdomen. Due to the upright posture of humans, the brain bends in relation to the spinal cord, making ventral mean "forward."

Nucleus

In cell biology, the nucleus in a cell is the cell nucleus, which contains the chromosomes, among other things. In neuroanatomy, the nucleus in the nervous system refers to a collection of cell bodies – known as gray matter in the central nervous system and ganglia in the peripheral nervous system.

dorsal

The positional term dorsal means "towards the back." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction perpendicular to the neural axis, i.e., upwards towards the head or backwards.

In animals that do not walk upright, the term is simpler, as it always means toward the back. Due to the upright posture of humans, the brain bends in relation to the spinal cord, making dorsal mean "upward."

Auditory cortex

The auditory cortex is a part of the temporal lobe that is involved in processing acoustic signals. It is divided into the primary and secondary auditory cortex.

ear

auris

The ear is not only the organ of hearing, but also of balance. A distinction is made between the outer ear with the auricle and external auditory canal, the middle ear with the eardrum and ossicles, and the actual hearing and balance organ, the inner ear with the cochlea and semicircular canals.

Auditory pathway

The auditory pathway refers to the nerve fibers that transmit acoustic information from the inner ear to the primary auditory cortex. In humans, the auditory pathway consists of five switching points: the spiral ganglion, the auditory nuclei in the brainstem, the inferior colliculus, the medial geniculate body of the thalamus, and the primary auditory cortex.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

lateral

A positional term – lateral means "towards the side." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction at right angles to the neural axis, i.e., to the right or left.

Midbrain

mecencephalon

The midbrain is the uppermost section of the brain stem. Its regions are located around the aqueduct, a canal filled with cerebrospinal fluid. Prominent structures include the tectum, tegmentum, and substantia nigra.

attention

Attention

Attention serves as a tool for consciously perceiving internal and external stimuli. We achieve this by focusing our mental resources on a limited number of stimuli or pieces of information. While some stimuli automatically attract our attention, we can select others in a controlled manner. The brain also unconsciously processes stimuli that are not currently the focus of our attention.

medial

A positional term – medial means "towards the middle." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction toward the body, away from the sides.

Hemisphere

The cerebrum and cerebellum each consist of two halves – the right and left hemispheres. In the cerebrum, they are connected by three pathways (commissures). The largest commissure is the corpus callosum.

Primary auditory cortex

The first processing station in the cerebral cortex for auditory information. The primary auditory cortex is located in the Heschl's gyrus and receives inputs from the medial geniculate nucleus of the thalamus. It is organized tonotopically – its neurons are arranged continuously according to frequency.

Temporal lobe

Lobus temporalis

The temporal lobe is one of the four lobes of the cerebrum and is located laterally (on the side) at the bottom. It contains important areas such as the auditory cortex and parts of Wernicke's area, as well as areas for higher visual processing; deep within it lies the medial temporal lobe with structures such as the hippocampus.

Two pathways: what and where

There are two pathways in the auditory system itself. The Dorsal pathway to areas in the Parietal lobe presumably processes spatial acoustic information. This pathway, sometimes referred to as the “where pathway,” probably comes into play when, for example, the hated sound of the alarm clock rings in the morning, which we reach for even when it is still dark in the room. The so-called “what pathway,” the Ventral pathway from the Auditory cortex to the superior temporal sulcus, is probably essential for identifying human speech, for example, among the multitude of acoustic stimuli.

Researchers such as neuroscientist Josef Rauschecker from Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. have found confirmation for this distinction in recent years. However, it is not entirely uncontroversial: “The hypothesis of these separate processing pathways is essentially nothing more than the adoption of corresponding hypotheses from the cortical visual system,” says Rudolf Rübsamen. “The extent to which this transfer to the auditory system has heuristic value is controversial among experts.”

Whatever the processing pathways may look like in detail, it is a long journey that auditory information takes from the ear to the brain. But for us, it is always worth it.

dorsal

The positional term dorsal means "towards the back." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction perpendicular to the neural axis, i.e., upwards towards the head or backwards.

In animals that do not walk upright, the term is simpler, as it always means toward the back. Due to the upright posture of humans, the brain bends in relation to the spinal cord, making dorsal mean "upward."

Dorsal pathway

The dorsal visual processing pathway is the part of visual information processing that is responsible for the spatial localization of objects and the perception of movement. It transmits visual information from the primary visual cortex (V1) and secondary visual areas (V2, V3) to the parietal lobes, where spatial orientation, motion analysis, and action planning take place.

Parietal lobe

Lobus parietalis

The parietal lobe is one of the four large lobes of the cerebral cortex. It is located behind the frontal lobe and above the occipital lobe. Somatosensory processes take place in its anterior region, while sensory information is integrated in its posterior region, enabling the handling of objects and spatial orientation. In addition, the parietal lobe is involved in attention, the recognition of body parts and objects, as well as linguistic and mathematical abilities.

ventral

A positional term – ventral means "towards the abdomen." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction perpendicular to the neural axis, i.e., downwards or forwards.

In animals (that do not walk upright), the term is simpler, as it always means toward the abdomen. Due to the upright posture of humans, the brain bends in relation to the spinal cord, making ventral mean "forward."

Ventral pathway

The part of the visual processing pathway that deals with size, shape, color, and ultimately object recognition. The what pathway runs from V1 and V2 to the areas of the temporal lobe.

Auditory cortex

The auditory cortex is a part of the temporal lobe that is involved in processing acoustic signals. It is divided into the primary and secondary auditory cortex.

ear

auris

The ear is not only the organ of hearing, but also of balance. A distinction is made between the outer ear with the auricle and external auditory canal, the middle ear with the eardrum and ossicles, and the actual hearing and balance organ, the inner ear with the cochlea and semicircular canals.

Further reading

- Rauschecker, J.: An expanded role for the dorsal Auditory pathway in sensorimotor control and Integration. Hearing Research. 2011; 271:16 – 25 (zum Abstract).

- Leaver, A., Rauschecker, J.P.: Cortical representation of natural complex sounds: effects of acoustic features and auditory object category. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010; 30(22):7604 – 7612 (zum Abstract).

dorsal

The positional term dorsal means "towards the back." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction perpendicular to the neural axis, i.e., upwards towards the head or backwards.

In animals that do not walk upright, the term is simpler, as it always means toward the back. Due to the upright posture of humans, the brain bends in relation to the spinal cord, making dorsal mean "upward."

Auditory pathway

The auditory pathway refers to the nerve fibers that transmit acoustic information from the inner ear to the primary auditory cortex. In humans, the auditory pathway consists of five switching points: the spiral ganglion, the auditory nuclei in the brainstem, the inferior colliculus, the medial geniculate body of the thalamus, and the primary auditory cortex.

First published on July 27, 2012

Last updated on October 17, 2025