What we actually hear

The ringing cell phone, the murmuring in the tram, the wind sweeping through the streets: there is hardly a place where there is true silence. But what is it that our ears pick up all the time?

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Steven van de Par

Published: 03.10.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

- What we hear are sound waves; vibrating surfaces cause air molecules to oscillate. These collide with each other and spread out in waves.

- The number of vibrations per second of a sound wave determines its frequency. It is measured in hertz (Hz).

- A young person can usually perceive frequencies between 16 hertz and 20 kilohertz (kHz).

- The faster a sound wave vibrates, the higher the tone perceived.

- A tone consists of sound waves with constant frequencies. We refer to a sound when overtones are added. Their frequency must correspond to a multiple of the fundamental tone.

When an ambulance with a siren passes by the listener very quickly, the sound appears to change. However, the sound made by the siren remains the same. So why does it sound different? This is due to a physical phenomenon known as the Doppler effect. It occurs when the source of the sound or the observer moves. When the ambulance drives toward the listener, its speed compresses the sound waves of the siren. This causes them to reach the ear at shorter intervals. The frequency is therefore higher and the tones sound higher than they actually are. However, as the vehicle moves away, it pulls the sound waves apart; the frequency becomes lower and the sound darker. Incidentally, the term Doppler effect does not come from something being doubled. The phenomenon was named after its discoverer, the Austrian physicist Christian Doppler (1803–1853).

ear

auris

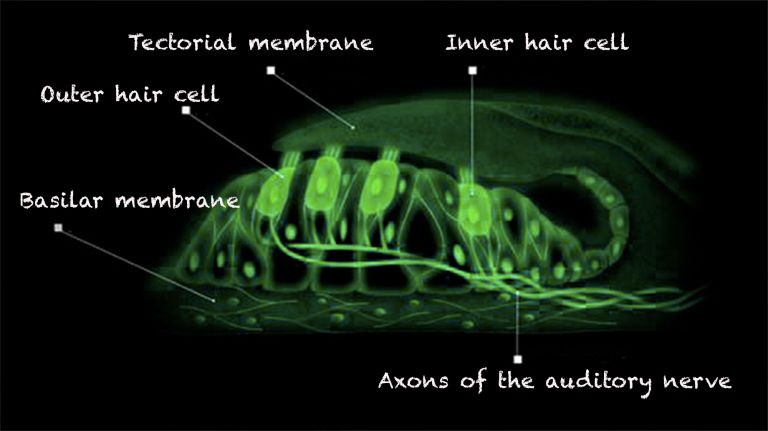

The ear is not only the organ of hearing, but also of balance. A distinction is made between the outer ear with the auricle and external auditory canal, the middle ear with the eardrum and ossicles, and the actual hearing and balance organ, the inner ear with the cochlea and semicircular canals.

Life enters through the ears – the mother's voice is the first connection the child in the womb has to the outside world. Later, thousands of sounds determine the day: the alarm clock that ends sleep, the warning honk of a car, the kind words of friends.

The tones, sounds, and noises that accompany everyday life are nothing more than waves invisible to the Eye that push air around and happen to hit the ears: sound waves. No chemical reactions are needed to produce them; physics is what's required here. Sound is the wave-like movement of particles, such as air or water. Without particles, for example in the vacuum of space, there are no sounds. The loud bang of exploding spaceships in science fiction films does not exist in reality.

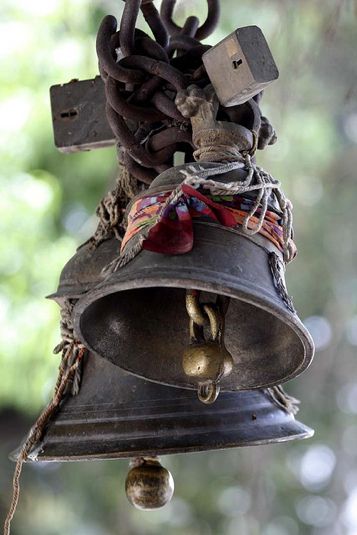

Sound is produced when a body vibrates. Examples include the membrane of a drum under the blows of a musician or our vocal cords, which vibrate when air flows through the larynx. How such a sound wave develops can be illustrated by the example of a church bell ringing. When the bell is struck, the clapper hits the metal wall and causes it to vibrate. When the metal bends outward, the molecules in the air are pushed away. They collide with neighboring particles, which in turn collide with their neighbors. When the metal swings back inward, more space is created between the particles and they are pulled apart. This creates a wave-like motion with dense and less dense parts. It spreads in all directions, much like the circular waves after a stone has been dropped into water.

Eye

bulbus oculi

The eye is the sensory organ responsible for perceiving light stimuli – electromagnetic radiation within a specific frequency range. The light visible to humans lies in the range between 380 and 780 nanometers.

Ten times faster than a car on the highway

At 343 meters per second (at 20 degrees Celsius), sound travels at breakneck speed through the air – the equivalent of a good 1,200 kilometers per hour. It travels even faster in water: at 1,480 meters per second. To reach the speed of sound, a submarine would have to travel at a good 5,300 km per hour, whereas an airplane would only need to travel at the aforementioned 1,200 km/h.

How loud a sound is depends on the distance from the sound source. Standing directly in front of a loudspeaker at a concert, you can experience firsthand what the booming music does to the air. This works best with a song that has a lot of drums or bass: when their sound waves hit the body very loudly, you perceive them as a kind of fluttering in your chest.

Why open-air stages are very high

When sound hits objects, the wave is weakened. To ensure that the music at an open-air festival is not swallowed up by the front rows of the audience, but reaches spectators further back, the stage is usually particularly high. This is not quite as important at concerts in halls, because the walls reflect the sound waves.

The effect of sound reflection is particularly noticeable in the mountains. If you shout towards a distant mountain wall, you will hear an echo. If you count the seconds until the echo returns, you can even calculate the distance to the wall. At 343 meters per second, the sound takes just under three seconds to travel one kilometer, or 1,000 meters. The sound wave must first reach the wall and then return, so it travels twice. Therefore, you have to divide the counted seconds by six to get the distance in kilometers. It works similarly during a thunderstorm: if you see lightning, you can count the seconds until you hear thunder. Unlike with an echo, the sound only travels once – from the point of impact to your ear. Therefore, the speed of sound can be used directly for the calculation: divide the number of seconds counted by three to get the distance in kilometers. The time it takes for the light from the lightning to reach the Eye is negligible because light is about a million times faster than sound.

ear

auris

The ear is not only the organ of hearing, but also of balance. A distinction is made between the outer ear with the auricle and external auditory canal, the middle ear with the eardrum and ossicles, and the actual hearing and balance organ, the inner ear with the cochlea and semicircular canals.

Eye

bulbus oculi

The eye is the sensory organ responsible for perceiving light stimuli – electromagnetic radiation within a specific frequency range. The light visible to humans lies in the range between 380 and 780 nanometers.

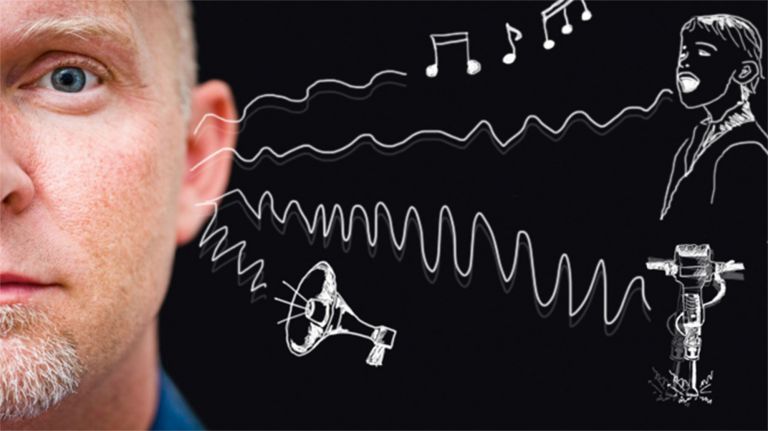

The frequency determines the pitch

Not all sound is the same. Whether we perceive a sound as melodious music or as loud noise depends on the nature of the vibrations. If they move in slow, regular waves, we perceive them as low tones. We interpret fast air vibrations as high-pitched sounds. To determine the speed of a wave, we measure its frequency, i.e., the number of vibrations per second. This is measured in hertz (Hz). The higher the hertz number, the higher the pitch.

Sounds that consist exclusively of sound waves with identical frequencies are called sine tones. They usually sound shrill, as can be heard in the ringing of old cell phones. We perceive the sounds of instruments as less shrill because, in addition to the fundamental tone that determines the pitch, they also have other sound waves at higher frequencies: the overtones. The condition for these not to distort the pure sound is that their frequency must be a multiple of the fundamental tone. The first overtone is twice as fast, the second three times as fast, the third four times as fast, and so on. With each overtone, the timbre changes. This is why an “a” sounds different on different instruments, even though the frequency of the fundamental tone is the same.

Recommended articles

Inaudible bat squeaks

When all overtones match the fundamental tone, acousticians refer to this as a “sound”. They use the term “noise” to describe a mixture of different frequencies that are not related to each other. Noise therefore cannot be assigned a clear pitch, only an intensity and a frequency spectrum.

Sounds and noises occur almost everywhere, but we do not perceive them all. A young, healthy person generally hears frequencies between 16 and 20,000 hertz. The squeaking of bats is usually so high-pitched that we humans cannot hear it – their sounds range from 15,000 to 150,000 hertz and are therefore largely in the ultrasonic range. The animals use their calls to orient themselves and locate prey via the echo reflected by their bodies. Only people with very good hearing are sometimes able to hear the lowest tones of the bat, perceived as a very high-pitched squeak.

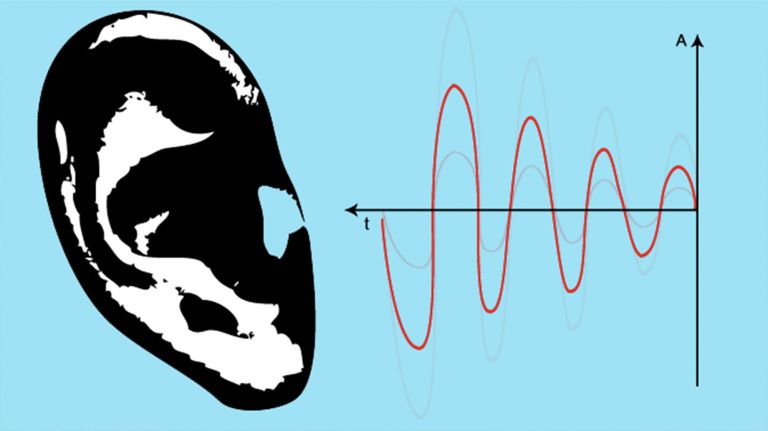

Sound pressure determines the volume

Not only the pitch but also the volume determines what can be understood and which sounds remain unheard. Once again, the shape of the sound wave is decisive here: We perceive particularly large wave crests as particularly loud. To determine the height of a wave, technicians measure its amplitude, i.e., the distance from the highest point of the wave crest to the original value. Sound consists of pressure differences, which is why amplitude is measured in pascals, the unit of measurement for pressure. The healthy human ear is capable of processing a huge range: from about 0.00002 pascals at the hearing threshold to 20 pascals at the pain threshold, it hardly misses anything.

Another unit of measurement for loudness is more commonly used in everyday life than pascals: decibels (dB). This allows the enormous spectrum of audible sound levels to be represented on a simple logarithmic scale: Zero decibels corresponds to the faintest audible sound. Whispering is around 30 decibels, city traffic is around 90 decibels, and the jet engines of an airplane roar at 140 decibels when taking off. Each increase of ten decibels is roughly equivalent to a doubling of the perceived volume.

Whether we perceive something as loud depends not only on the decibels – frequency is also important. When music is played very quietly, it is the mid-range tones that we can just about hear. The bass tones, on the other hand, “disappear”.

But whether loud or quiet, pleasant or annoying, sound is almost everywhere. In order to understand sounds and noises, distinguish between them, and assign meaning to them, they must first be converted into a language that the brain can understand. This happens when sound waves find their way through the passages, convolutions, and cavities of the ears, triggering nerve impulses. Then a little physics turns into music.

ear

auris

The ear is not only the organ of hearing, but also of balance. A distinction is made between the outer ear with the auricle and external auditory canal, the middle ear with the eardrum and ossicles, and the actual hearing and balance organ, the inner ear with the cochlea and semicircular canals.

Published on July 27, 2012

Last updated on October 3, 2025