Full Blast to the Ears

Whether in the subway, in a café, or outside on the street – noise is everywhere. But this constant acoustic companion is not only stressful and harmful to our hearing and health; it also damages the brain.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Eckhard Friauf

Published: 18.11.2025

Difficulty: serious

- Noise can destroy the fine hairs of the sensory cells in the cochlea, thereby damaging our hearing.

- Noise makes you ill, not only but especially when it occurs continuously and at night. As a chronic stressor, it affects the cardiovascular system and is a risk factor for hypertension, coronary heart disease, and stroke. It also increases the risk of metabolic disorders, mental illness, and dementia.

- Noise impairs brain development.;the Auditory cortex is particularly affected.

- Cognitive performance also suffers from constant exposure to noise.

stroke

Cerebral apoplexy

In a stroke, the brain or parts of it are no longer supplied with sufficient blood, which impairs the supply of oxygen and glucose. The most common cause is a blockage in an artery (ischemic stroke), less commonly a hemorrhage (hemorrhagic stroke). Typical symptoms include sudden visual disturbances, dizziness, paralysis, speech or sensory disturbances. Long-term consequences can include various sensory, motor, and cognitive impairments.

dementia

Dementia

Dementia is an acquired deficit of cognitive, social, motor, and emotional abilities. The most well-known form is Alzheimer's disease. "De mentia" means "without mind" in English.

Auditory cortex

The auditory cortex is a part of the temporal lobe that is involved in processing acoustic signals. It is divided into the primary and secondary auditory cortex.

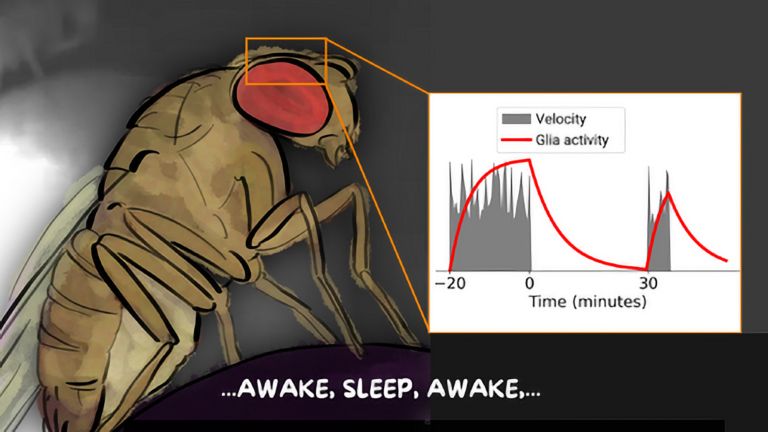

Not all people are equally sensitive to noise. US scientists at Harvard Medical School in Boston have investigated this phenomenon. They asked 12 test subjects to sleep in the laboratory and found that how undisturbed someone sleeps seems to depend on the number of so-called sleep spindles. These are high-frequency wave patterns in the EEG that the brain produces during slumber. The more frequently these sleep spindles appeared in the EEG, the less the test subjects were disturbed during sleep. The sleep spindles probably reflect a blockage between the Auditory cortex and the thalamus. And thalamus's control center must pass on acoustic information before it is processed in the auditory Cortex. Accordingly, regular, rhythmic sleep spindles act like neurobiological earplugs.

EEG

An electroencephalogram, or EEG for short, is a recording of the brain's electrical activity (brain waves). Brain waves are measured on the surface of the head or using electrodes implanted in the brain itself. The time resolution is in the millisecond range, but the spatial resolution is very poor. The discoverer of electrical brain waves and EEG is the neurologist Hans Berger (1873−1941) from Jena.

Auditory cortex

The auditory cortex is a part of the temporal lobe that is involved in processing acoustic signals. It is divided into the primary and secondary auditory cortex.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

How wonderful, this silence! Anyone who has the opportunity to travel to the desert can look forward to a very special experience: a silence beyond imagination – completely unfamiliar to most ears. Because everyday life is characterized by a constant backdrop of noise: traffic, a train rattling by, aircraft noise, a television playing here, a radio blaring there, cell phone chatter everywhere, a dog barking, and a group of retirees chatting away over coffee at the next table.

This constant noise level is not a modern invention. Historical sources report that ancient Rome was already plagued by terrible noise. And according to the satirist Juvenal (around 100 AD), it robbed many people of their sleep – some even became so ill from the constant din that they died.

Noise makes you ill

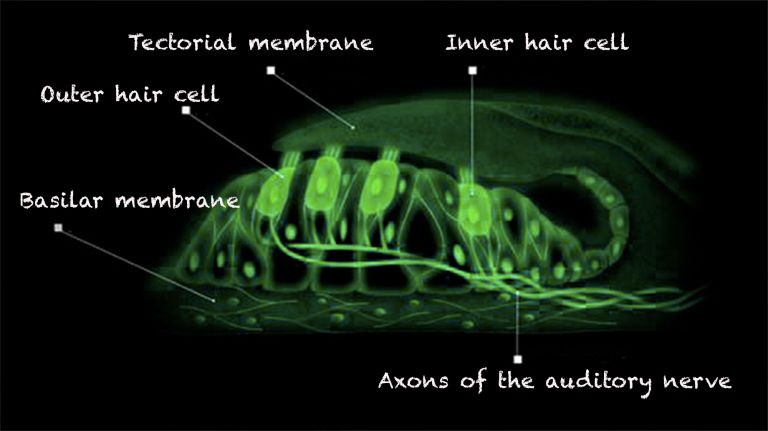

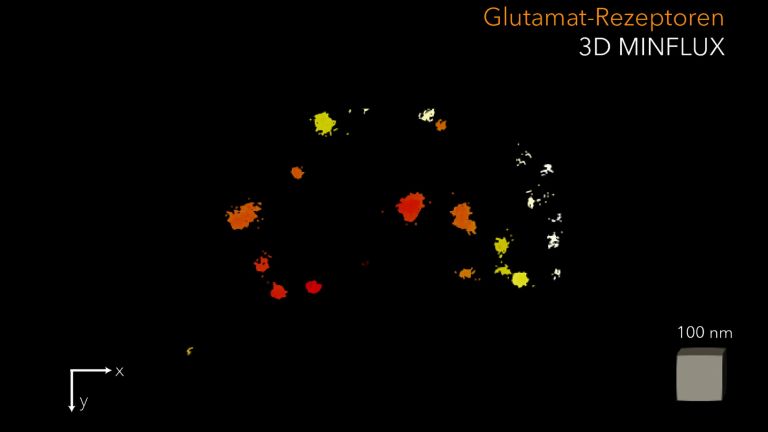

Then as now, noise is a nuisance, can make you ill, and can impair cognitive performance. And it damages your hearing. If there is a loud bang, for example when a New Year's Eve firecracker explodes nearby, the sound vibrations can bend or even break the fine hairs of the Hair cells in the inner ear (stereocilia). Because it is the stereocilia that pick up sound so that it can ultimately be transmitted to the brain as a neural signal, the affected person becomes hard of hearing and usually experiences a soft hissing or whistling sound in their ear. With a little luck, the hairs will straighten up again and hearing will recover. However, if the damage is more severe or the noise pollution is constant, the problem becomes permanent.

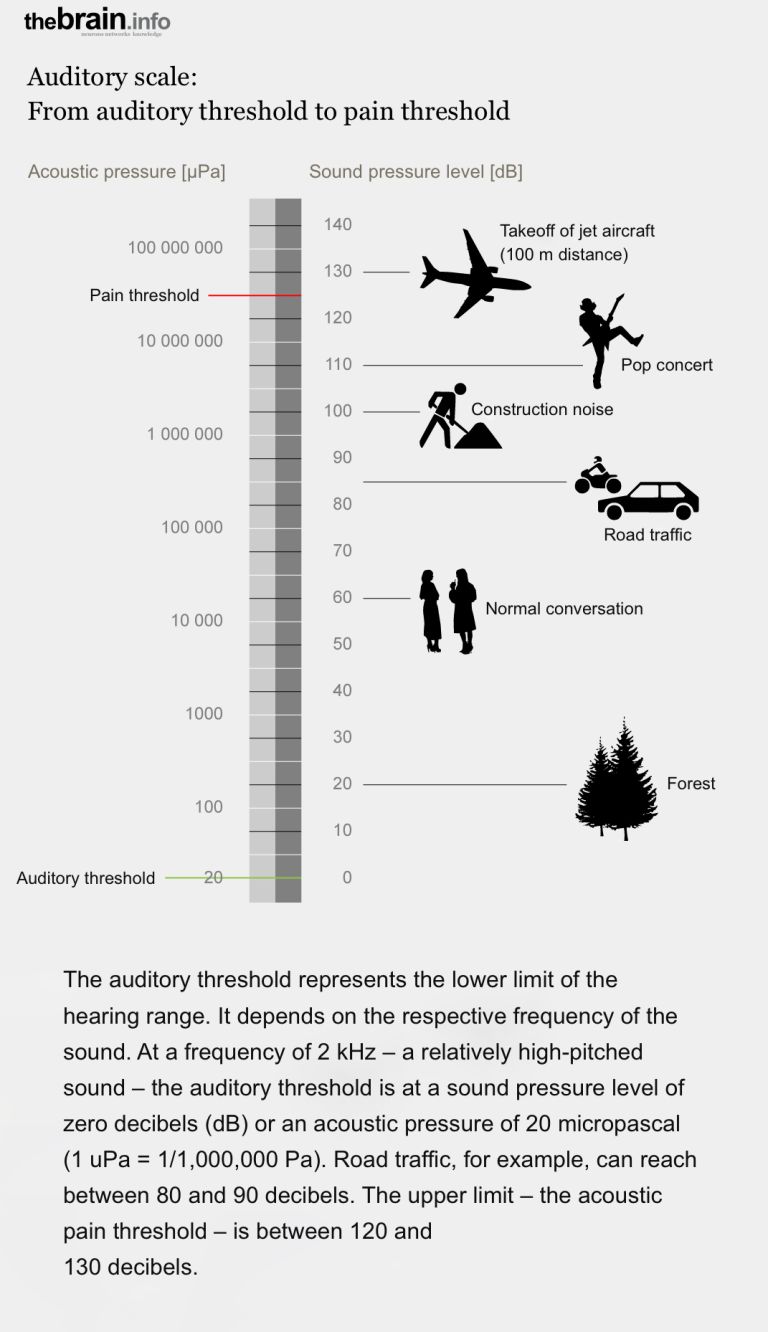

The pain threshold for noise is between 120 and 130 decibels. At this level, people instinctively cover their ears. But even continuous exposure to 85 decibels, such as from a busy road, leaves its mark on the hearing. Scientists have also discovered that noise is harmful to health. High blood pressure, arteriosclerosis, heart attacks, stomach ulcers – all of these can be attributed to prolonged noise pollution. For example, the risk of heart attack is higher for men living in noisy residential areas – with average daytime street noise levels of more than 65 decibels – than for men living in quieter areas. This was shown in a study by the German Federal Environment Agency in 2004. Even the youngest children are affected, as the agency's staff discovered in a study conducted in 2009: children whose rooms face a busy road tend to have slightly higher blood pressure.

The reason: noise is a stressor. More than 90 decibels trigger a Fight-or-flight response The body releases increased amounts of the stress hormones Adrenaline and noradrenaline and activates energy reserves. When it gets really loud, i.e., above 120 decibels, Cortisol is also released in people who are awake. In people who are asleep, the stress response occurs much earlier, with consequences for the cardiovascular system. A 2003 study by the German Federal Environment Agency found that people who must endure an average noise level of 55 decibels or more outside their bedroom window at night have almost twice the risk of high blood pressure as those whose noise level was below 50 decibels.

Hair cells

Sensory cells in the inner ear located in the organ of Corti and the semicircular canals. The hair cells in the organ of Corti are responsible for transducing (converting) the vibrations into electrical potentials. Each of these sensory cells has hair-like protrusions of varying lengths, called stereocilia. These are interconnected. The movement of these stereocilia caused by the vibrations is the key to signal transduction in the hair cells.

ear

auris

The ear is not only the organ of hearing, but also of balance. A distinction is made between the outer ear with the auricle and external auditory canal, the middle ear with the eardrum and ossicles, and the actual hearing and balance organ, the inner ear with the cochlea and semicircular canals.

Fight-or-flight response

According to Walter Cannon's theory from 1929, animals – just like humans – respond to acute threats with increased arousal. They have the choice between fight or flight. Both reactions are triggered by the same feeling of stress.

Adrenaline

Along with dopamine and norepinephrine, it belongs to the catecholamines. Adrenaline, also known as epinephrine, is the classic stress hormone. It is produced in the adrenal medulla and causes an increase in heart rate and heartbeat strength, thus preparing the body for increased stress. In the brain, adrenaline also acts as a neurotransmitter (messenger substance), where it binds to so-called adrenoreceptors.

Cortisol

A hormone produced by the adrenal cortex that is primarily an important stress hormone. It belongs to the group of glucocorticoids and influences carbohydrate and protein metabolism in the body, suppresses the immune system, and acts directly on certain neurons in the central nervous system.

Recommended articles

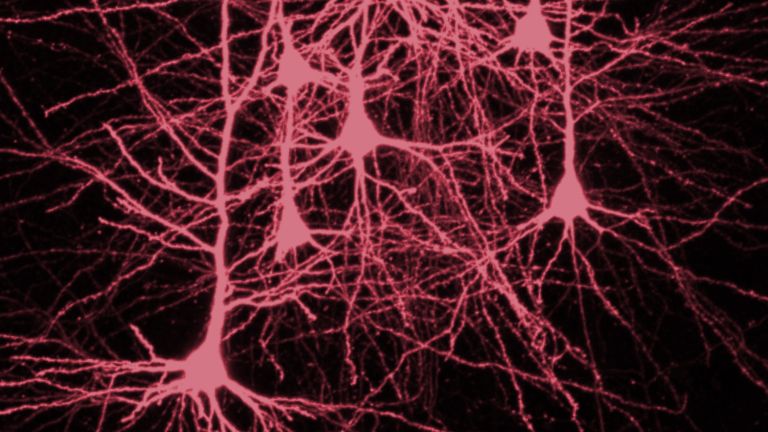

Noise damages the brain

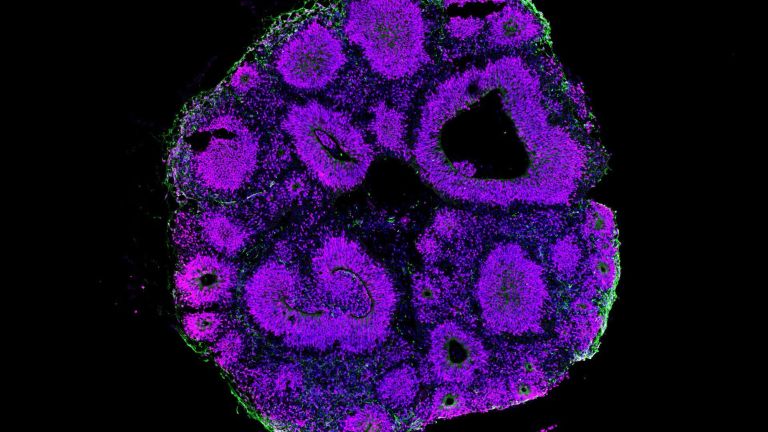

Noise also leaves its mark on the brain. This was proven in 2003 by neuroscientists Edward Chang and Michael M. Merzenich from the University of California, San Francisco. The US researchers exposed newborn rats to broadband noise for several months, which, according to the scientists, can be compared to normal ambient noise (unstructured continuous noise) in everyday life. Although this did not cause any direct damage to the hearing of the baby rats, it did delay the development of their Auditory cortex During the first month of life, Neuron clusters form in this area that react selectively to certain sound patterns and frequencies. In the rodents that were exposed to continuous noise, this maturation process was still not complete even after several months. Admittedly, such massive exposure is anything but typical. However, later, less extreme studies confirmed the negative effects on brain maturation – even in the prefrontal cortex!

“The negative aspect is that noise can have serious effects on brain development,” Chang commented on his publication. Although rats are not humans, it is conceivable that similar circumstances could also leave lasting marks on human babies. But the researchers did not only have bad news. “On the positive side, the period during which affected children can be treated and catch up seems to be longer” than previously assumed. Once the young rats were relieved of the constant noise, they soon caught up in their maturation process – even as adult animals.

Nevertheless, great caution is advised when it comes to constant noise exposure. A whole series of studies has shown that it also impairs cognitive performance in schoolchildren and adults. In 2008, scientists at RWTH Aachen University asked test subjects to take part in a test in a simulated office. They played sounds through headphones to the volunteers that corresponded to the murmur of a conversation in the next room – sometimes at a volume as if it were coming through a thick wall, sometimes through a thin one. At the same time, the test subjects were asked to memorize numbers and later reproduce them in the order they had memorized them. As a control, they listened to the conversation at full volume in further rounds, and on another occasion, they were allowed to memorize without disturbance.

The result: the test subjects found all background conversations disturbing. This was also reflected in their cognitive performance: the test subjects' Memory was impaired, regardless of whether the conversation was whispered or at normal volume. Schoolchildren are already disturbed by acoustically unfavorable rooms that echo, as researchers in Aachen discovered in another study in 2010.

Young people in particular, but also older people, are considered to be particularly sensitive to noise. And even age-related hearing loss does not protect against noise. It is true that as hearing loss progresses, the threshold at which a person perceives sound at all and can therefore perceive it as noise increases. But in the range in which they can hear, older people are actually more sensitive. “The dynamic range becomes smaller. The range in which hearing begins is higher, but the pain threshold decreases,” says hearing researcher Holger Schulze, professor of experimental otolaryngology at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg. And every bit of damage contributes to progressive hearing loss. Reason enough, then, to appreciate and protect our hearing and its extraordinary capabilities. Silence, by the way, has a distinctly healing effect. It relaxes and strengthens the psyche, allowing us to reconnect with ourselves. It doesn't necessarily have to be in the desert; a local forest works just as well.

Auditory cortex

The auditory cortex is a part of the temporal lobe that is involved in processing acoustic signals. It is divided into the primary and secondary auditory cortex.

Neuron

A neuron is a specialized cell in the nervous system that is responsible for processing and transmitting information. It receives signals via its dendrites and transmits them via its axon. Transmission occurs electrically within the neuron and, between neurons, usually chemically via synapses.

Memory

Memory is a generic term for all types of information storage in the organism. In addition to pure retention, this also includes the absorption of information, its organization, and retrieval.

Further reading:

- Homma et al; Auditory Cortical Plasticity Dependent on Environmental Noise Statistics; Cell Rep 2020; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2020.03.014

- Bures et al; The influence of developmental noise exposure on the temporal processing of acoustical signals in the Auditory cortex of rats; Hearing Research 2021; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2021.108306

- Hayes et al; Neurophysiological, structural, and molecular alterations in the prefrontal and auditory cortices following noise-induced hearing loss; Neurobiology of disease 2024; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2024.106619

- Gheller et al; The effects of noise on children‘s cognitive performance; Environment and Behavior (EAB) 2023; https://doi.org/10.1177/00139165241245

- Jafari et al; The effect of noise exposure on cognitive performance and brain activity patterns; Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences 2019; https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2019.742

Plasticity

Neuroplasticity

The term neuroplasticity describes the ability of synapses, nerve cells, and entire areas of the brain to change structurally and functionally depending on the degree to which they are used. Synaptic plasticity refers to the adaptation of the signal transmission strength of synapses to the frequency and intensity of incoming stimuli, for example in the form of long-term potentiation or depression. In addition, the size, interconnection, and activity patterns of different areas of the brain also change depending on their use. This phenomenon is referred to as cortical plasticity when it specifically affects the cortex.

Auditory cortex

The auditory cortex is a part of the temporal lobe that is involved in processing acoustic signals. It is divided into the primary and secondary auditory cortex.

First published on July 19, 2012

Last updated on November 18, 2025