Nerve Cells in Conversation

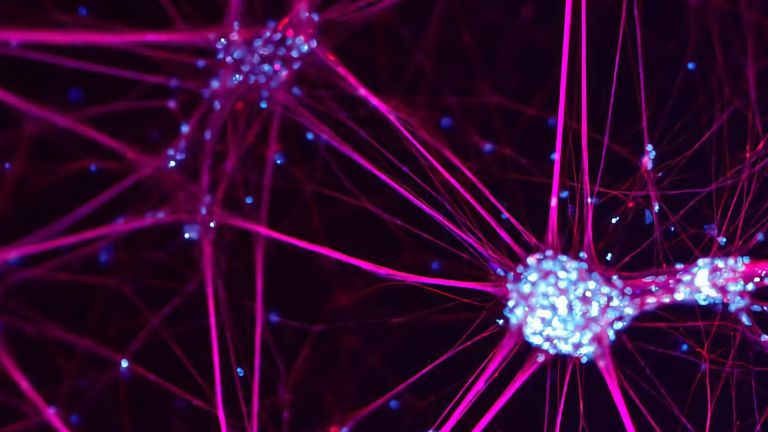

Around 86 billion neurons must constantly communicate with each other so that humans can feel, act, and think. Complex chemical and electrical processes take place in thousands of cells in milliseconds – for a single meaningful action.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Hans-Dieter Hofmann, Prof. Dr. Anne Albrecht

Published: 16.04.2012

Difficulty: intermediate

- Within a neuron, an incoming signal is transmitted electrically.

- Signals between two neurons are usually transmitted chemically via neurotransmitters.

- Electrical transmission works according to the all-or-nothing principle: only when the strength of the signal exceeds a threshold value is the action potential generated in the axon.

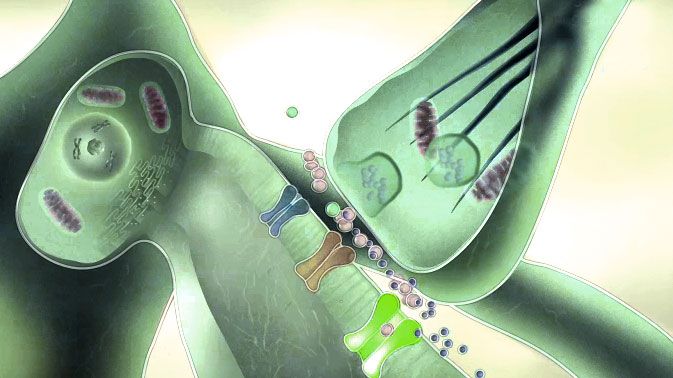

- The electrical signal of the action potential is “translated” into a chemical signal at the synapse: action potentials in the axon cause the release of messenger substances – neurotransmitters – into the gap between the sender and receiver cells.

- The receiving cell can absorb the neurotransmitters via receptors and translate them back into an electrical signal, the postsynaptic potential.

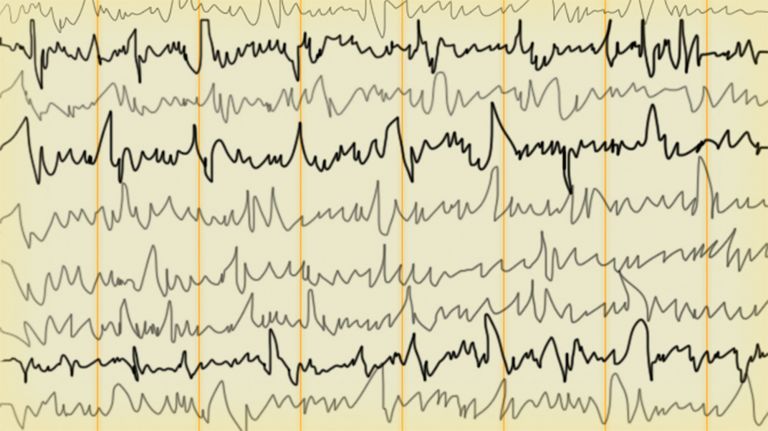

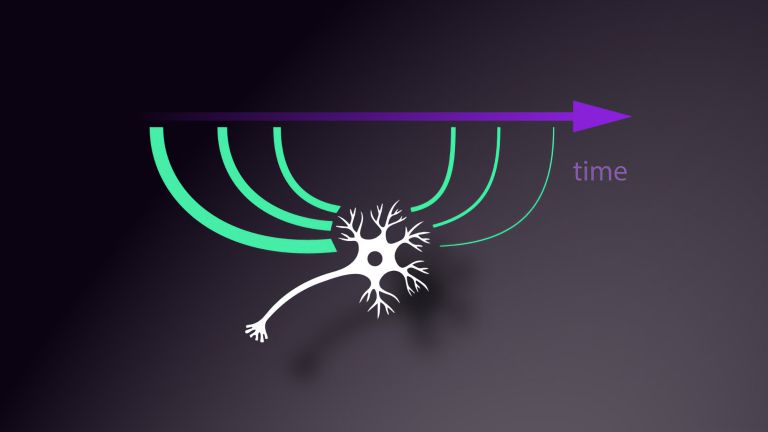

- The number and frequency of action potentials is variable and plays a decisive role in determining the urgency of information transmission.

As long as a neuron does not “fire,” it is in a resting state. In this phase, a certain voltage, the resting potential, prevails at the outer skin of the cell, the membrane. If the neuron is stimulated accordingly, for example by another nerve cell or sensory input, a changed electrical voltage is generated at the membrane of the axon, which propagates along the axon to its contact points with other nerve cells. This is referred to as the action potential, which lasts about one millisecond in humans.

At the contact point with the next cell, the synapse, the action potential triggers the release of chemical messengers (neurotransmitters). This is referred to as the presynaptic side. The neurotransmitters now enter the synaptic cleft and reach the downstream nerve cell – the postsynaptic side beyond the synaptic cleft. There are specific receptors for the neurotransmitter there, and its binding can trigger a postsynaptic potential at the postsynaptic membrane. If the impulse is strong enough – or if further excitatory impulses arrive at other synapses – another action potential can be triggered in the downstream cell.

The transition from resting potential to action potential occurs when certain ions flow in and out of the cell membrane of the axon. In the resting state, there are more potassium ions inside the axon, while there are more sodium ions outside the cell. Since potassium ions can migrate through the membrane to the outside more easily in the resting state than sodium ions can in the opposite direction, there is a positively charged environment on the outside of the membrane and a negatively charged environment inside the cell. This creates a voltage across the membrane of approximately -70 millivolts. When a suitable stimulus occurs, ion channels open briefly in the membrane, allowing positively charged sodium ions to flow in very quickly. Now the potential inside becomes more positive and more channels open, a process referred to as depolarization. Only when this is strong enough, i.e., when it exceeds a certain threshold value, does the action potential occur as a kind of explosive repolarization of the membrane (“all-or-nothing principle”).

While the action potential rushes along the axon like a wave, repolarization already begins at the axon hillock near the cell body: Potassium ions exit through their own channels, which are now opening, while the sodium channels close again. The imbalance of charges decreases until the resting state is reached again. Active sodium-potassium pumps then ensure that the sodium ions that have flowed in are transported back out, and the potassium ions are transported in. Everything is now back to normal.

In addition to chemical synapses, electrical synapses have also been discovered. So-called “gap junctions” play a role in this electrical communication between two cells – channels consisting of proteins that connect the cell fluids of two neurons. This allows electrical signals to pass ion currents through these channels directly from cell to cell without detours. “Gap junctions allow many cells to be synchronized with each other over a greater distance,” says Nils Brose, director of the Department of Molecular Neurobiology at the Max Planck Institute for Multidisciplinary Sciences. “When one cell receives a signal, it is immediately transmitted to the other cells, as they are connected to each other like plugs and sockets.” This mobilizes larger groups of nerve cells in a very short time.

Although this sounds very efficient, this purely electrical form of transmission is more common in simpler animals such as crabs, where it controls rapid escape reactions, for example. In humans, the need for more complex forms of transmission has prevailed in the course of evolution.

Imagine you had to get the participants of a conference to behave in a collaborative, meaningful way. The catch: the conference has a billion participants, and you only have fractions of a second to do it!

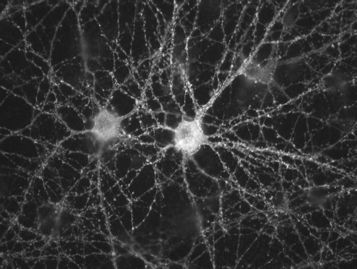

Impossible, right? But in the body, this works constantly and with an impressive success rate. In order for specific actions or emotions to be possible, large groups of nerve cells in the brain must work together and communicate with each other. ▸ Cells: specialized workers of the brain

The nerve cells understand each other perfectly – with the help of electrical and chemical signals.

Neurons are the sprinters among cells

When you roll up a portion of spaghetti with a fork because you're hungry, you do so thanks to a kind of “silent post” of various neurons: the central nervous system activates the arm and hand muscles with the help of nerve cells that specialize in motor functions – so-called motor neurons – so that you can grasp the fork. At the same time, sensory neurons constantly send info to the brain, like the position of the hand and the pressure of the fingers on the fork. This info is processed in the brain by groups of nerve cells that control the arm, hand, and fingers, so the rest of the movement can be precisely controlled – again via the motor neurons. This is how you manage to actually hold the long, slippery noodles on your fork.

It sounds simple. But the flow of communication is extremely complex and involves millions of nerve cells that analyze, inhibit, or amplify information through a combined electrical and chemical process and ultimately transmit the result.

From axon to synapse

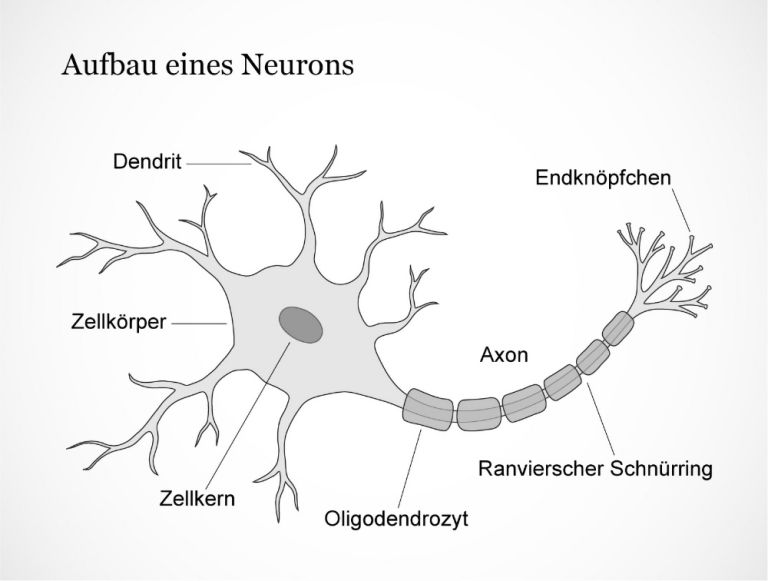

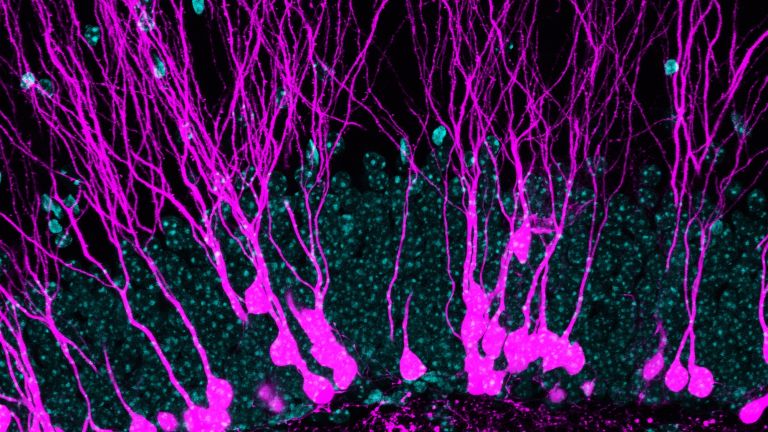

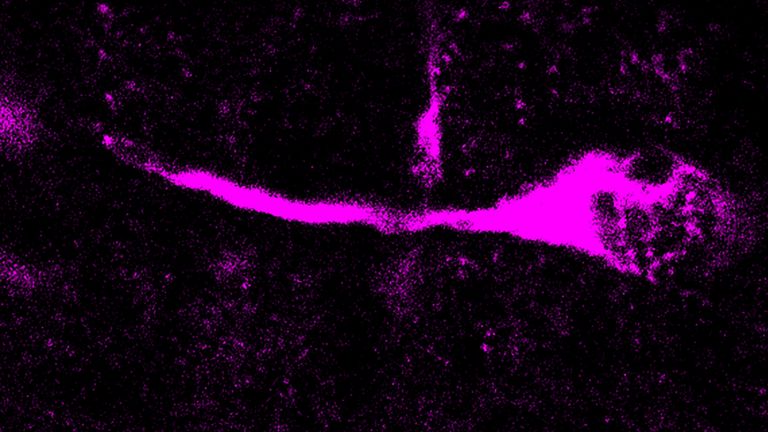

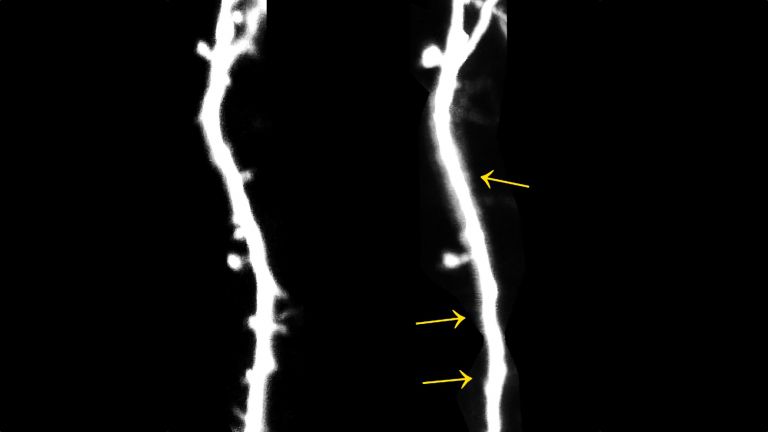

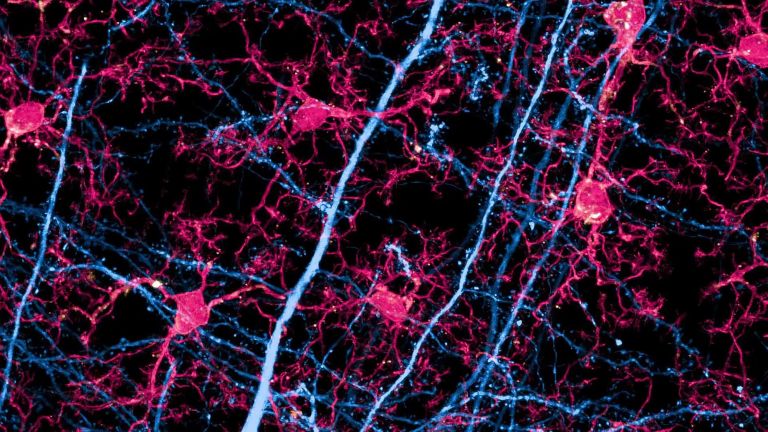

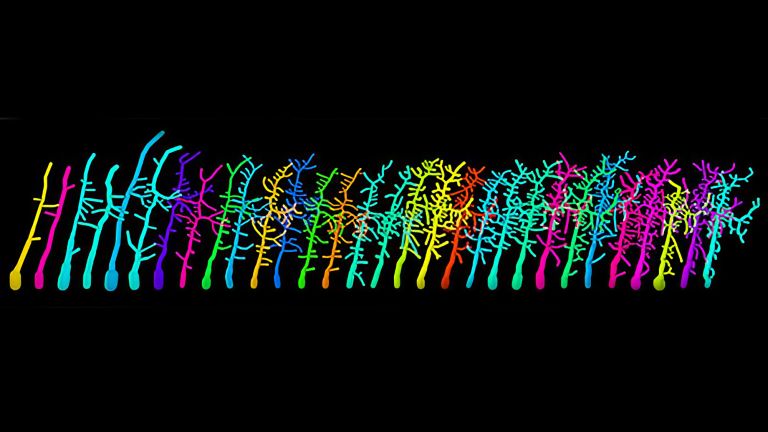

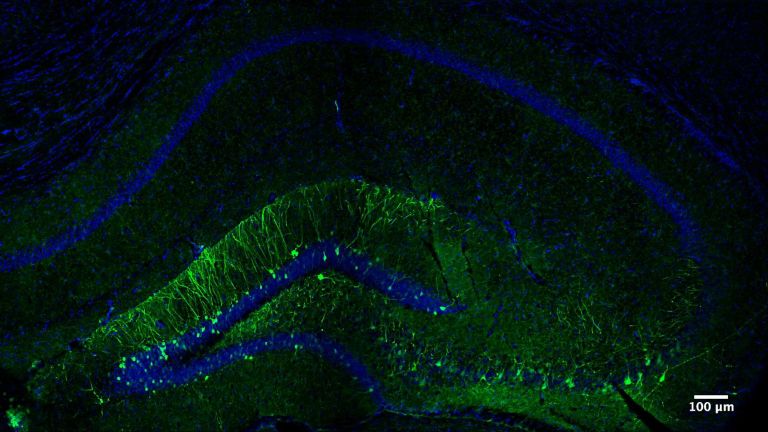

To understand this, we need to briefly recall the structure of a nerve cell: Put simply, a neuron usually consists of a cell body and several branches that are in contact with other nerve cells and are used to receive or send information. The sending extension is called an axon, which can be over a meter long. The receiving extensions are called dendrites. A single neuron can interact with 100,000 to 200,000 fibers from other nerve cells.

If the incoming signals from other nerve cells are strong enough, i.e., if a certain threshold of excitation is exceeded, the neuron fires: An electrical impulse, known as an action potential, shoots along the axon toward the synapse (see info box). Depending on the type of nerve cell, this happens slowly or rapidly: in extreme cases, the excitation can reach a speed of 120 meters per second.

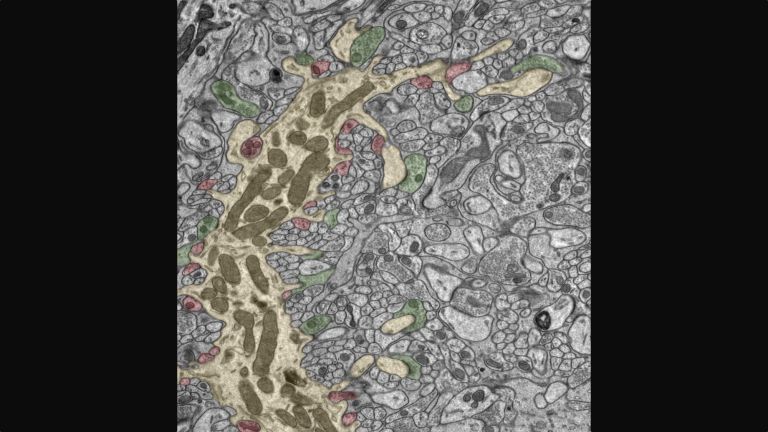

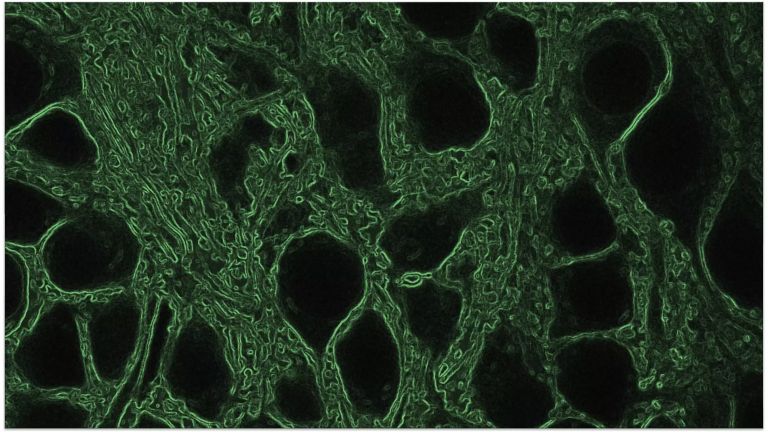

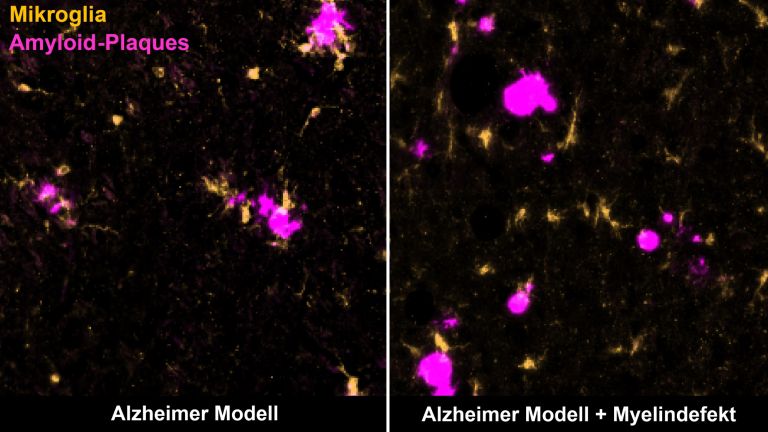

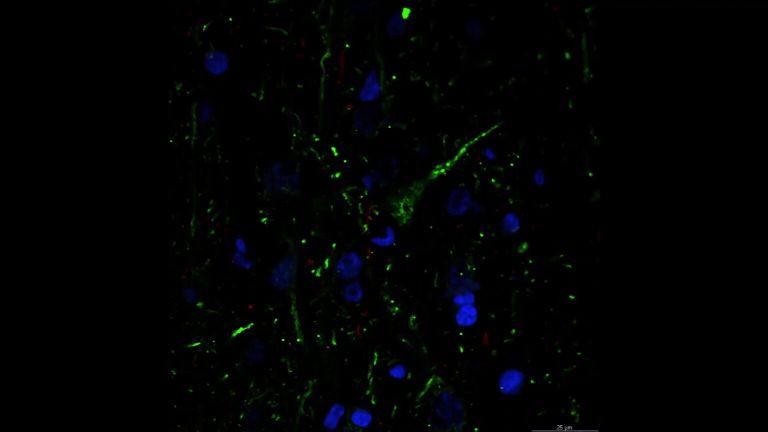

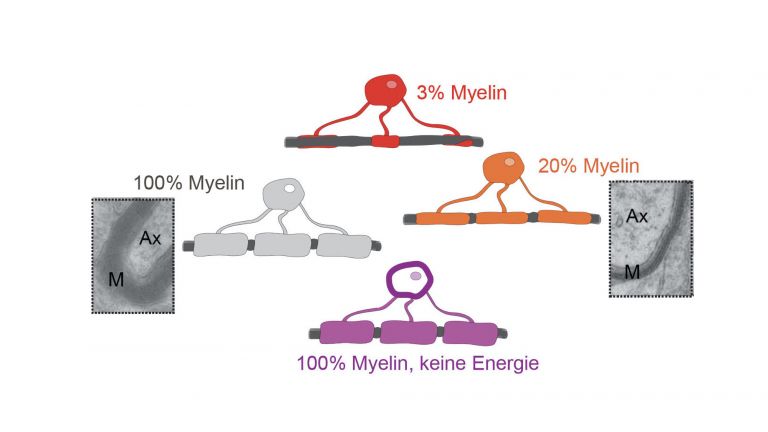

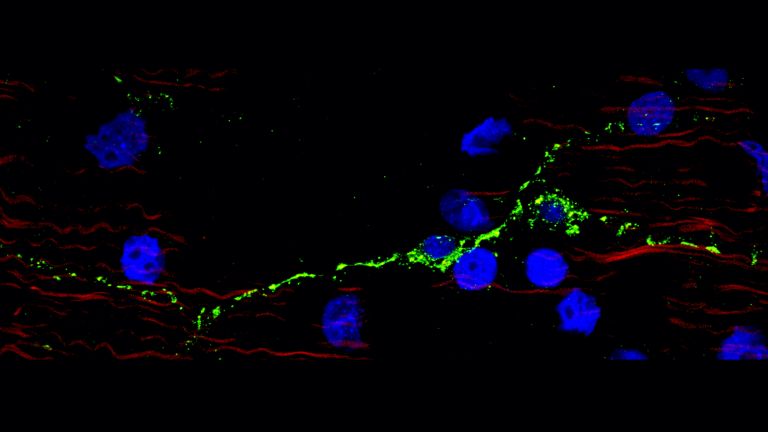

The speed of electrical transmission depends not only on the thickness of the axon (thick axons conduct faster, thin ones slower) but also on certain helper cells that surround the nerve fiber: in the brain and spinal cord, these are oligodendrocytes, and in the peripheral nerves, Schwann cells. Both are two types of glial cells. They often form dense, spiral-shaped sheaths around the axon, which are strung together like beads on a chain and interrupted by small gaps. The sheaths are called myelin sheaths, the gaps between them Ranvier's nodes. The myelin sheaths function like the insulation on a cable. No action potential can arise at these points, which means that the electrical impulse does not propagate continuously, but simply skips over the insulated areas. This makes transmission significantly faster.

Chemistry bridges the gap

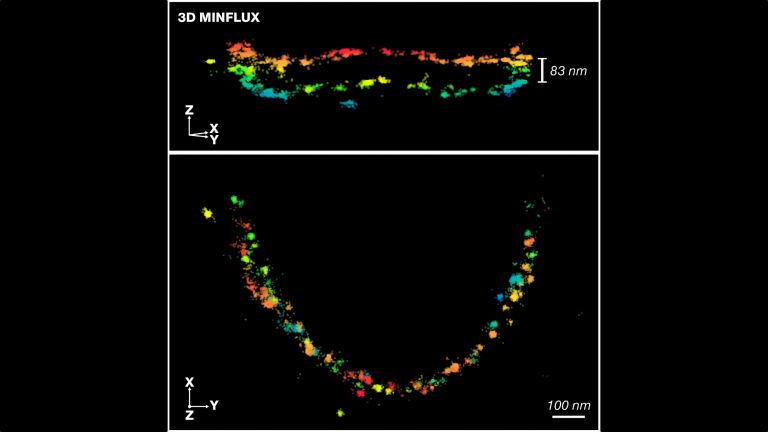

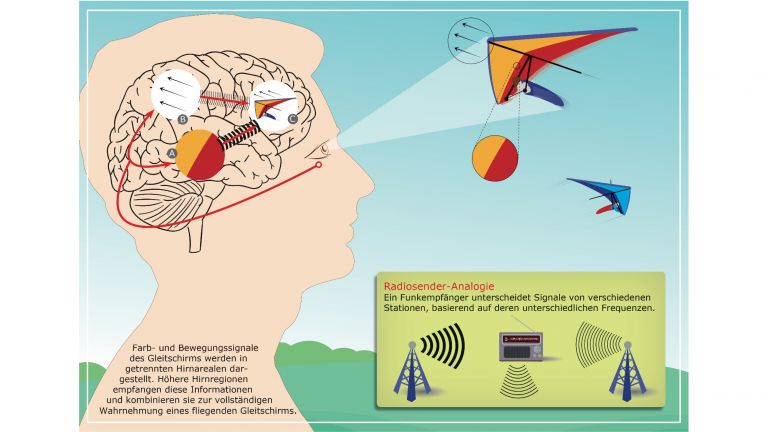

The action potential finally reaches the end of the axon, the synaptic terminal. This is the point of contact with another nerve cell. Synapses are the central switching points for information transmission in the brain. Each nerve cell has thousands of them, in extreme cases even more than 100,000. However, because the synaptic terminals of the sender cell do not directly touch the receiver cell, there remains a tiny gap of 20 to 50 nanometers between the two. To overcome this barrier, most synapses use chemical messengers – although there are some that work purely electrically (see info box).

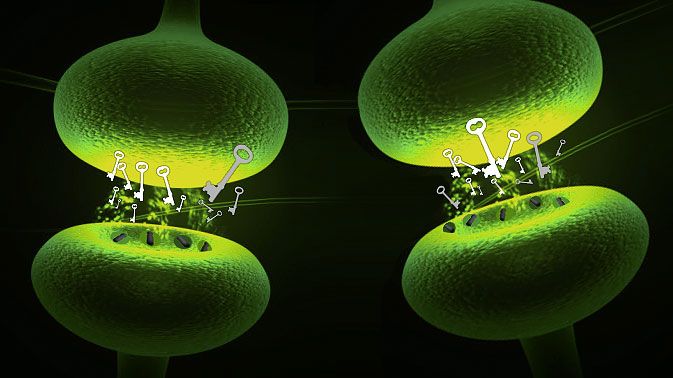

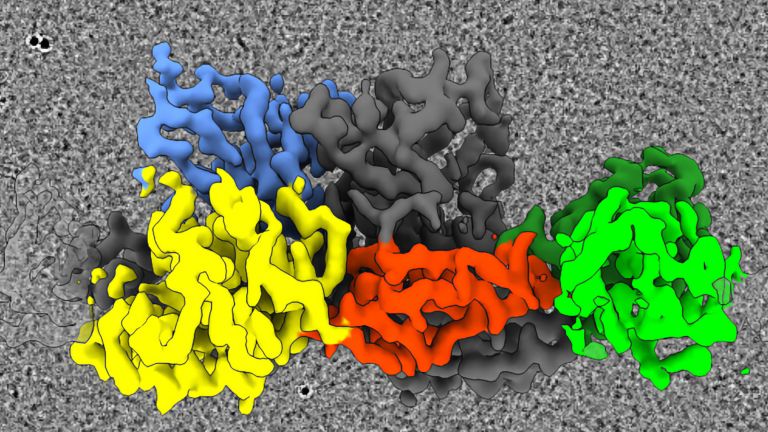

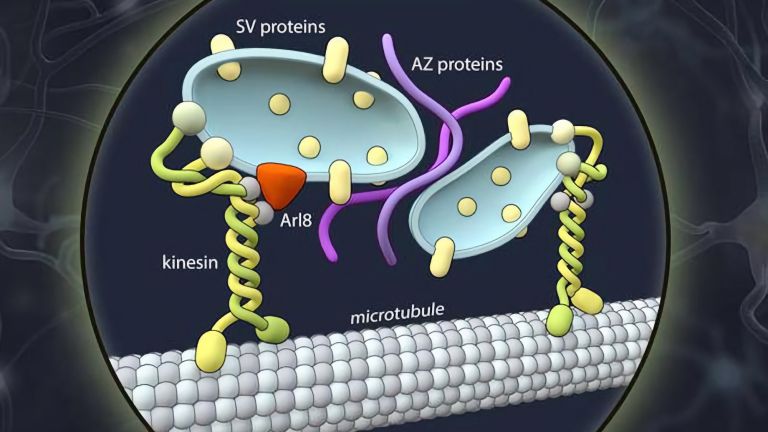

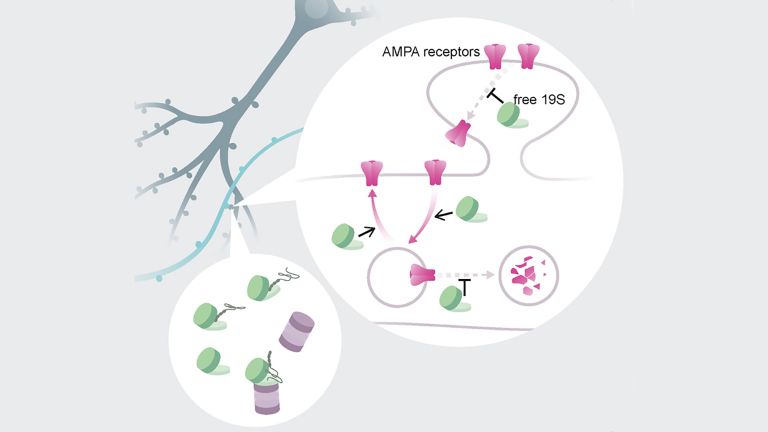

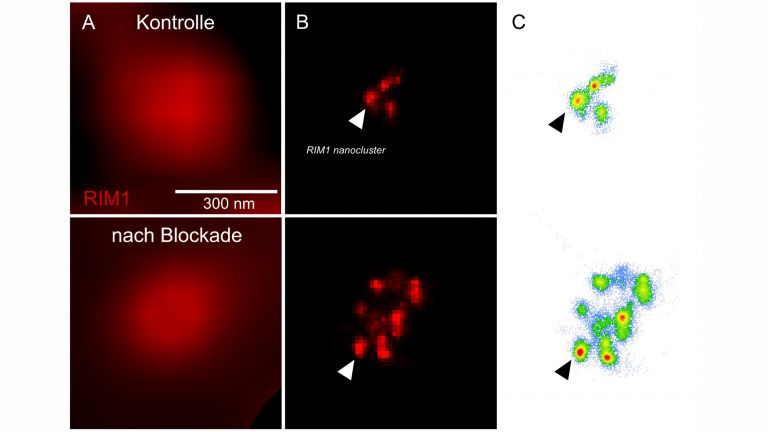

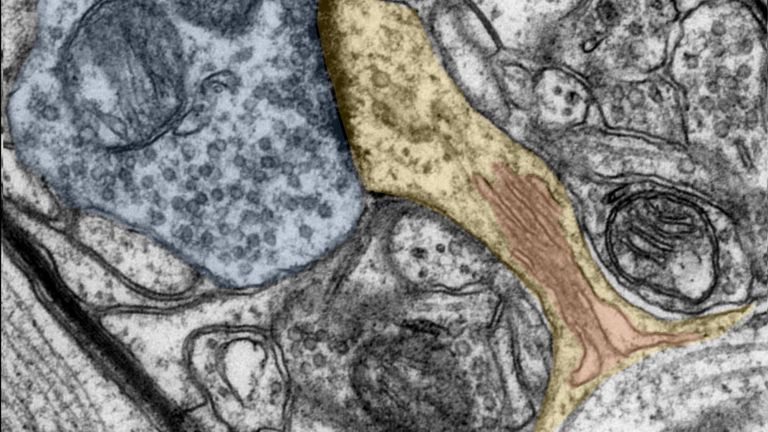

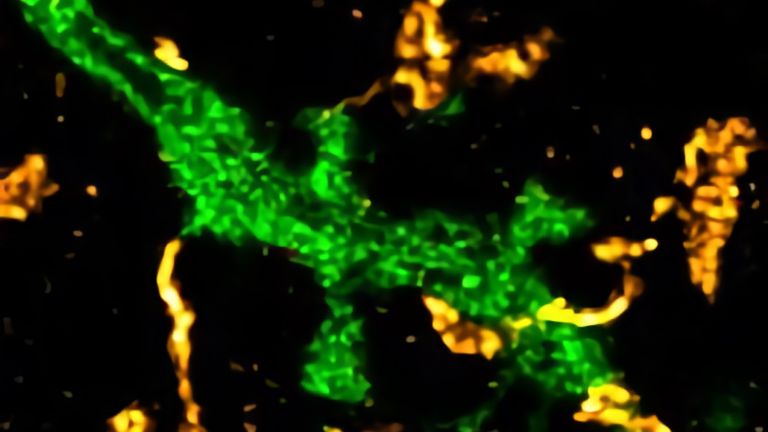

In chemical synapses, after the arrival of an action potential, the so-called synaptic vesicles – tiny bubbles measuring around 40 nanometers – fuse with the cell membrane and release messenger substances into the gap. These so-called neurotransmitters can cross the gap that separates the presynaptic cell from the postsynaptic cell. ▸ Neurotransmitters: Messenger molecules in the brain

At the postsynaptic neuron, there are specific receptors for the information: the receptor molecules. Each receptor is specialized for a specific neurotransmitter, like a key and a matching lock. The neurotransmitters generate what is known as the postsynaptic potential in the receiving cell, a change in the membrane potential of the neuron: the chemical signal is thus converted back into an electrical signal. And here again, if the cell receives a sufficiently strong signal or if the sum of the various signals arriving at the same time is large enough, the postsynaptic cell generates a new action potential in the initial part of its axon, the axon hillock, and the impulse is transmitted.

Recommended articles

There is controversy at the cellular level

But beware: the effect of neurotransmitters is not always excitatory, i.e., stimulating. Some synapses can act as inhibitors, preventing the formation of a new action potential (all-or-nothing principle). Neil R. Carlson provides a vivid example of this in Physiology of Behavior: If I want to carry a pot of freshly cooked pasta to the dining table but burn my fingers in the process, I would actually have to drop the pot. In many cases, however, the brain simultaneously receives the message that this reaction would cause a mess on the floor. “Don't drop it” is therefore the signal sent by the brain to the spinal cord and motor neurons – ultimately, dozens of sensory neurons, hundreds of motor neurons, and thousands of neurons in the brain are involved in this “discussion process” of excitatory and inhibitory processes, at the end of which the reflex to drop the pot is not acted upon.

This signal must arrive quickly and be so emphatic that it overcomes the impulse to drop the pot. But how can particularly important signals be emphasized? After all, the action potential that is decisive for transmission is generated according to the all-or-nothing principle: if the stimulus remains below the threshold value, the cell does not fire any impulse at all; if it exceeds it, the action potential is generated, but its shape and size are always the same, regardless of how much the threshold value has been exceeded.

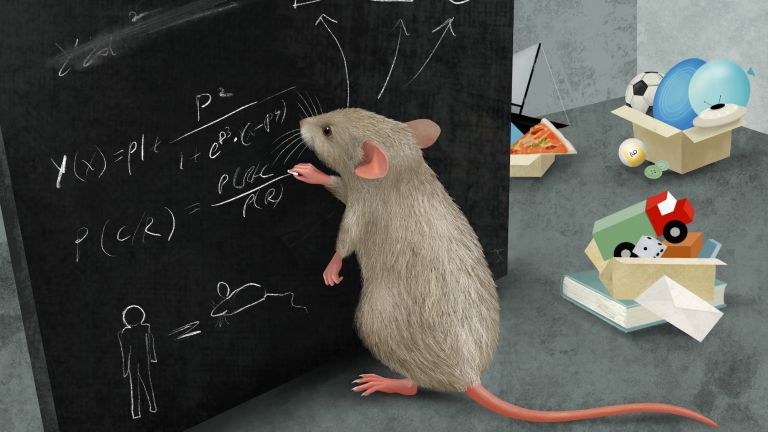

The solution: The information about the strength of an excitation is encoded in the number of action potentials and their temporal distance from each other, the frequency. Particularly strong stimuli trigger a particularly large number of action potentials in quick succession. A nerve cell can fire up to 500 times per second. For the receiving cell, this means that a large number of postsynaptic potentials are generated and add up.

Practice makes perfect

Messages can be encoded in a differentiated manner in the sending cell. Biochemist Nils Brose from the Max Planck Institute for Multidisciplinary Sciences in Göttingen emphasizes that the interaction between action potentials and neurotransmitters is a highly complex molecular process: "It involves a whole cascade of proteins – this is referred to as excitation-secretion coupling. This coupling can be dynamically altered. For example, by changing proteins or by using one protein more than another.“ The effectiveness of the coupling of action potential and the release of neurotransmitters can therefore vary.

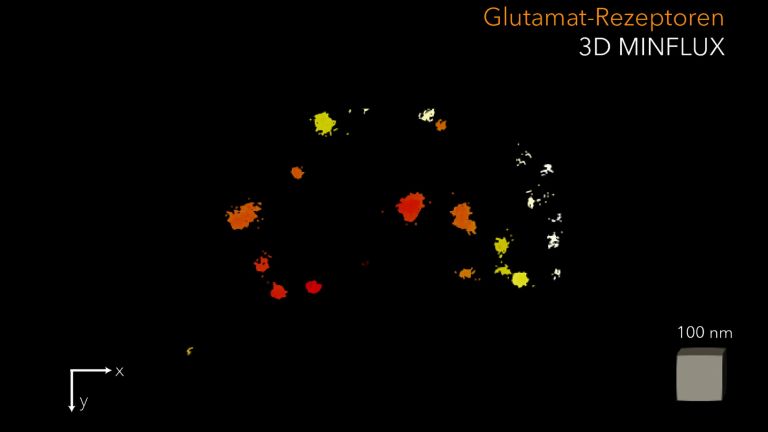

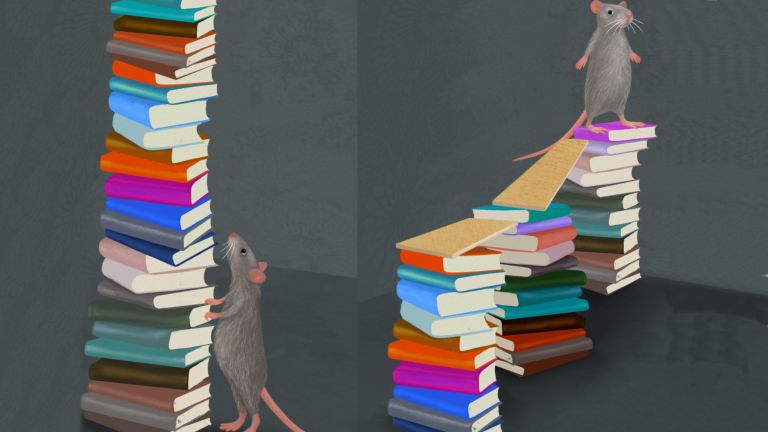

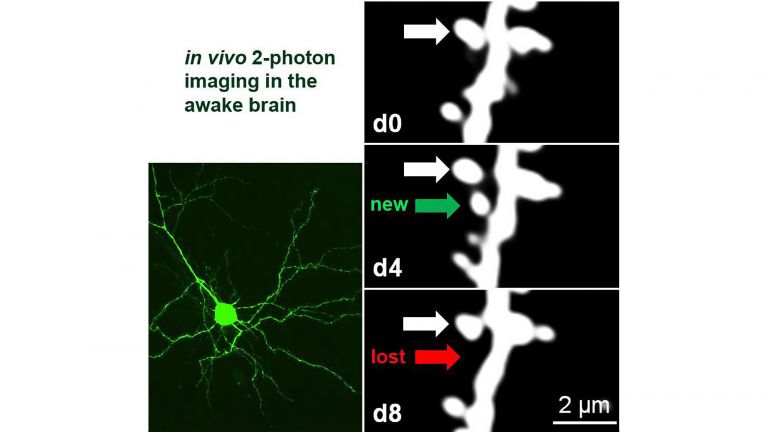

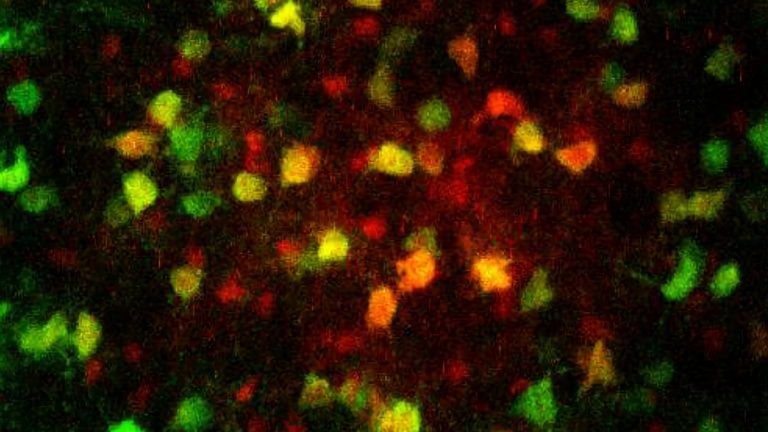

And the receiving cell can also dynamically alter the transmission performance: ”The more receptors there are on the receiving side, the more sensitive it is. This means that even with the same amount of transmitter released, the receiving side can still be excited to varying degrees," says Brose. And this is also dynamically changed in the brain: Researchers assume that in learning processes, for example, the post-synapse becomes more sensitive in the long term.

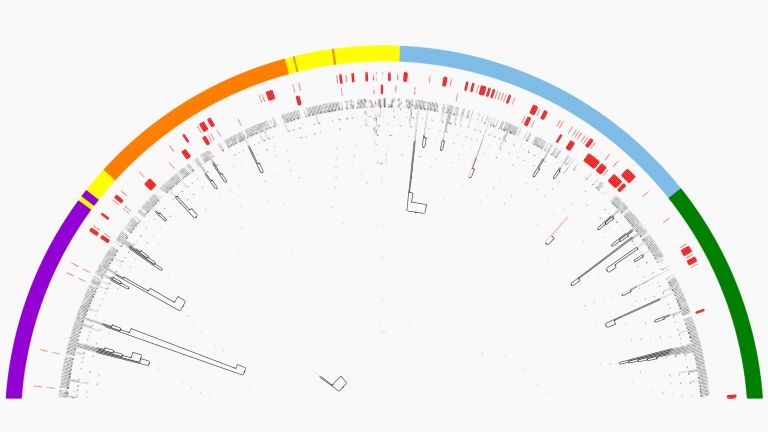

But how do the approximately 100 trillion synapses in our brain actually know which nerve cell to pass the information on to? This knowledge is determined during the development of the nervous system, says Brose: “If you look at a specific region of the brain, you can see that the cells are interconnected in a very regulated manner.” There must be mechanisms that enable the cell to identify the correct recipient cells. “It is assumed that they recognize each other on the basis of surface proteins and connect according to the lock-and-key principle.” However, there are still many unanswered questions in this exciting field of developmental biology within the neurosciences.

It turns out that our nerve cells are masters of communication and true multi-taskers: Amidst a flood of information that flows into them within milliseconds via thousands of inhibitory and excitatory synapses, they maintain an overview and forward the integrated impulses across large networks – always in collaboration with other cells. This is a feat that we often fail to achieve even in interpersonal communication. But the same applies to both humans and cells: practice makes perfect. If synaptic transmission performance can be improved through experience and learning processes, then there is still hope for chatting with mom or the boss.

First published on April 16, 2012

Last updated on November 25, 2025