On the Scent of Cell Communication

The work of early brain researchers was an adventure: frog legs twitched on clotheslines, bitter enmities were cultivated, Nobel Prizes were shared. It was worth it: the findings of yesteryear form the basis of today's research.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Herbert Schwegler, Prof. Dr. Anne Albrecht

Published: 22.12.2023

Difficulty: intermediate

- Until the end of the 19th century, it was unclear whether the brain was a coherent network of fused neurons or consisted of individual cells.

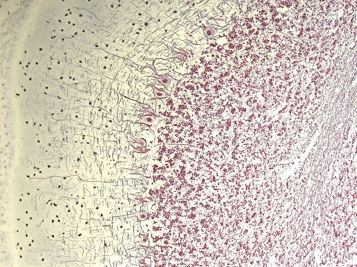

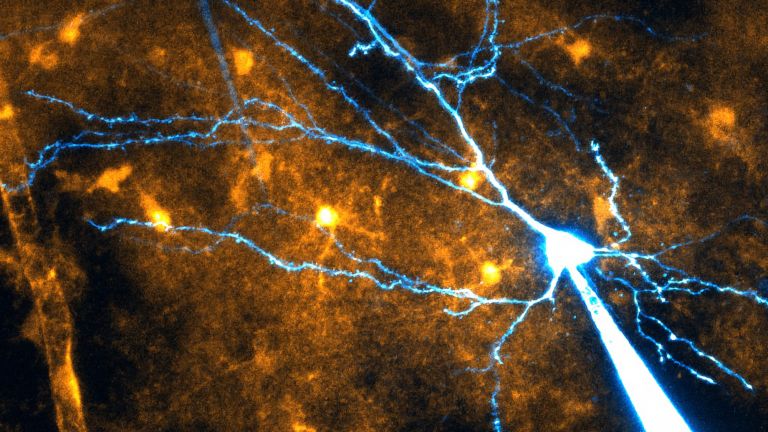

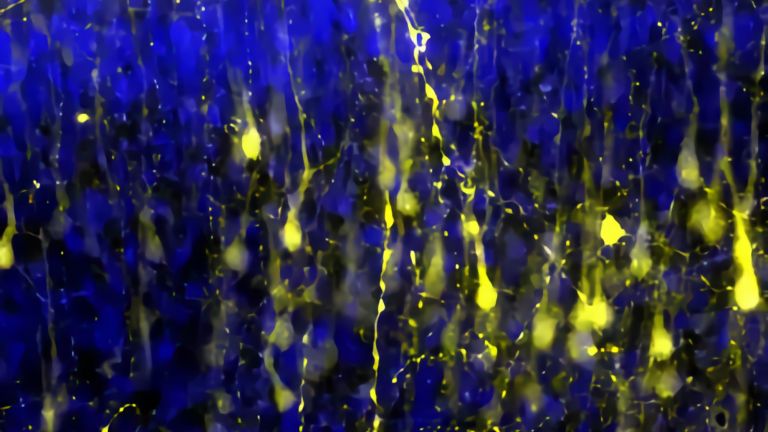

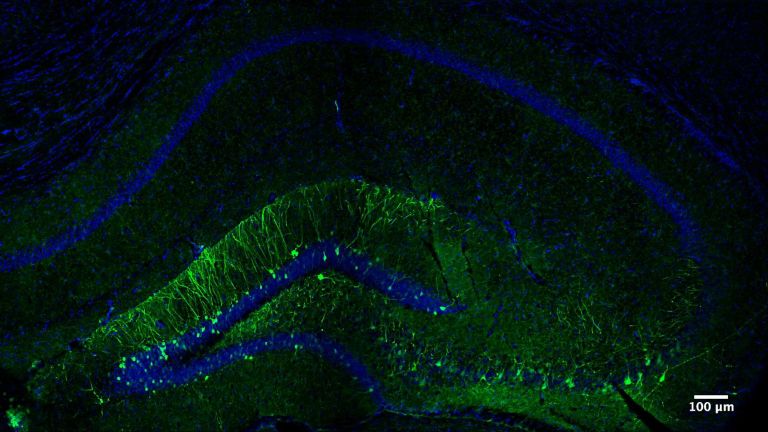

- It was only through Camillo Golgi's discovery of silver nitrate staining that individual neurons became visible – a technique that enabled Santiago Ramón y Cajal to formulate the neuron doctrine: discrete nerve cells are the basic building blocks of the brain.

- Luigi Galvani, Hermann von Helmholtz, Lord Adrian, and others were interested in the electrical conduction of nerves and nerve cells.

- Otto Loewi discovered neurotransmitters.

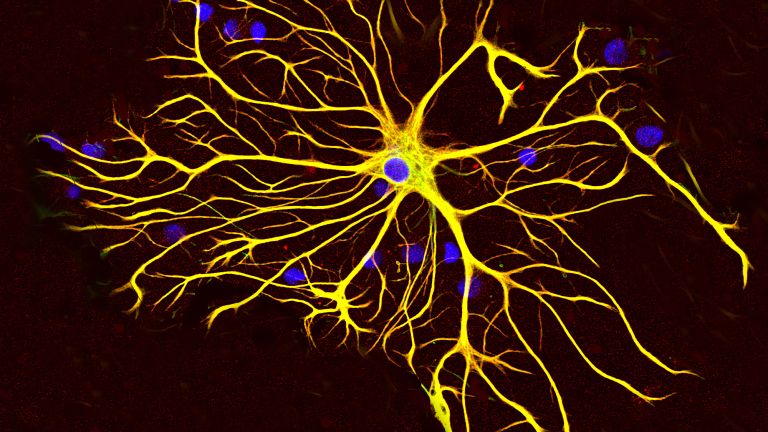

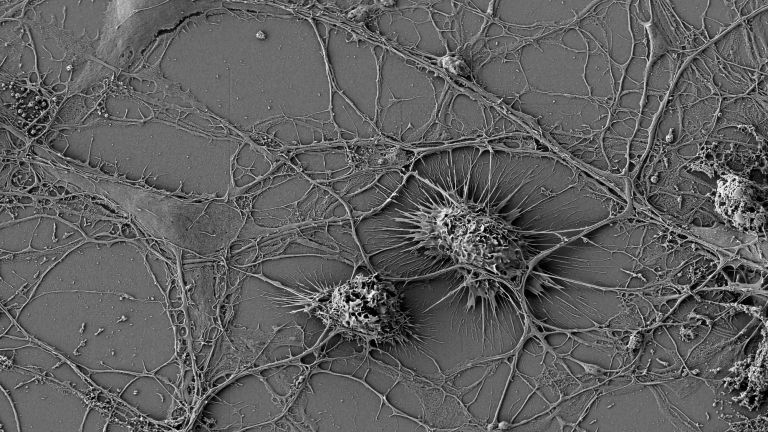

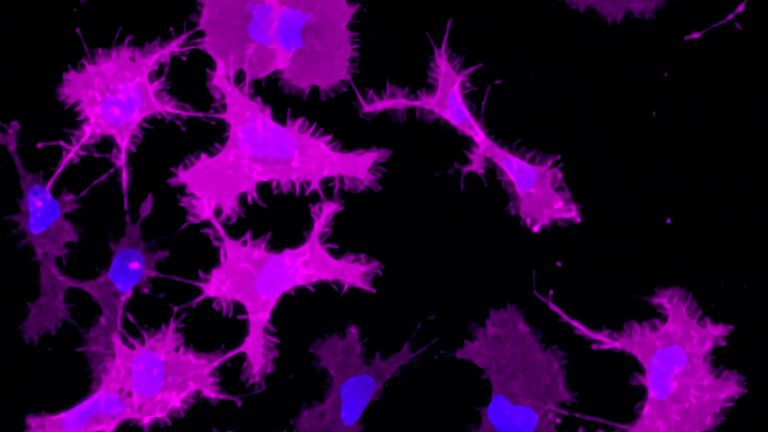

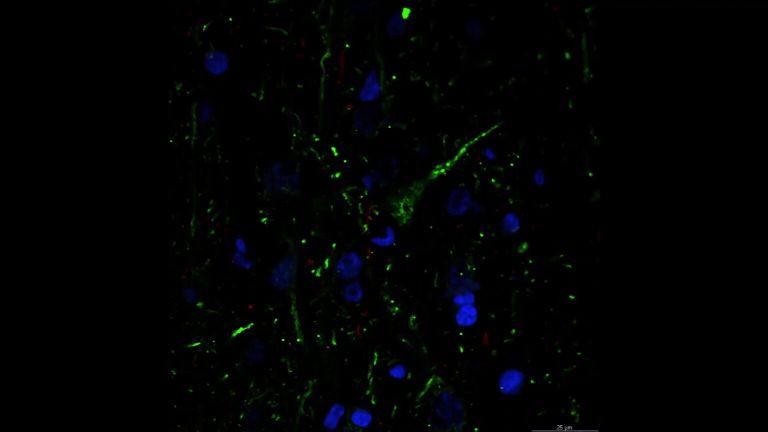

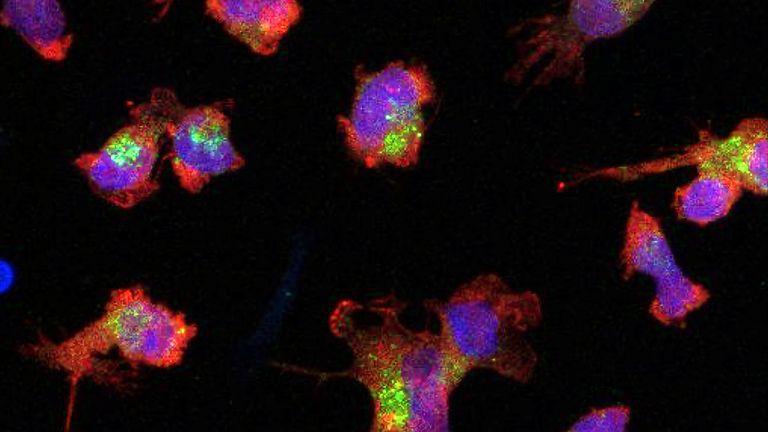

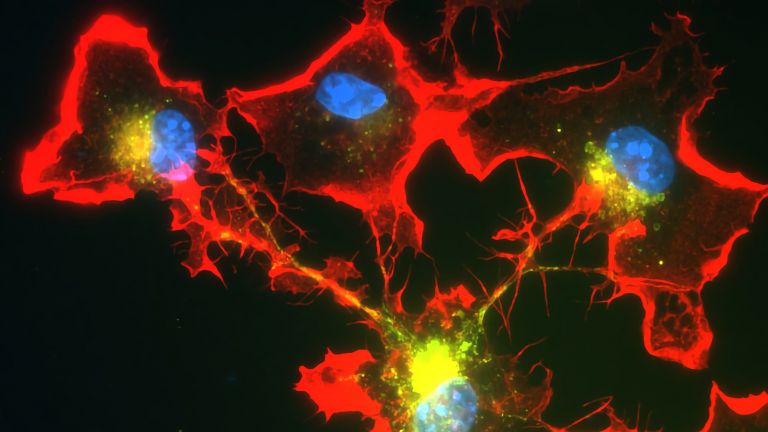

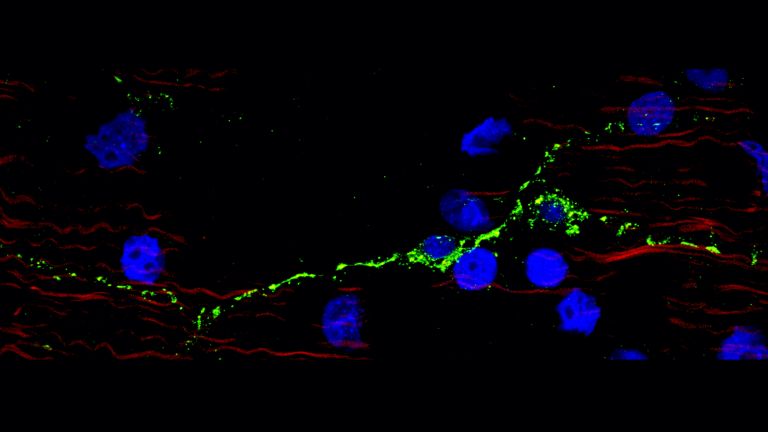

The human body consists of an estimated 100 trillion cells, all specialized for specific tasks. Cells that process and transmit information are called nerve cells or neurons. Together with the glial cells, they form the central and peripheral nervous systems

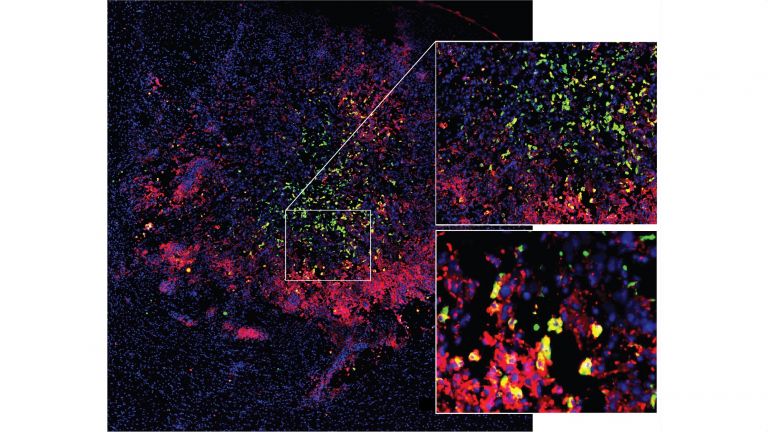

According to the latest estimates there are 86 billion neurons in the brain. They are responsible for our ability to speak, act, and feel. Their diverse interconnections create networks that can process even complex stimuli. Today's brain researchers devote their work and sometimes their lives to exploring them. Yet all stand on the shoulders of giants; today's knowledge would be unthinkable without the pioneers of the past. With experiments that were sometimes adventurous, they laid the foundation for today's research and discovered what holds our brain together at its core.

The problem of visibility

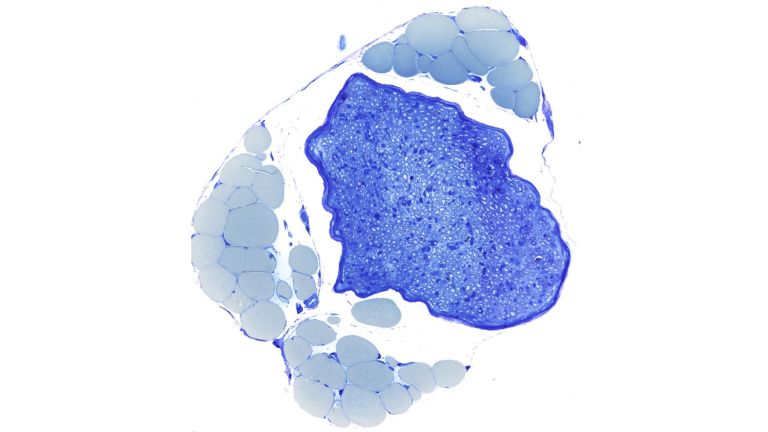

It wasn't easy. Neither the networks nor the individual brain cells can be seen with the naked eye. Robert Hooke, a founding member of the venerable Royal Society, had already discovered and named cell-like structures in plants in 1665 using one of the early microscopes. Yet, it was not until 1839 that Theodor Schwann showed that plants and animals actually consist of independent cells, however, no one knew exactly what these brain cells looked like.

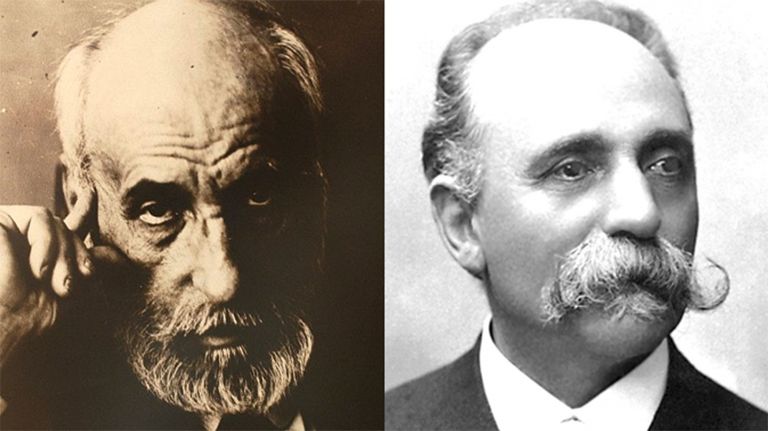

Conflict-ridden staining

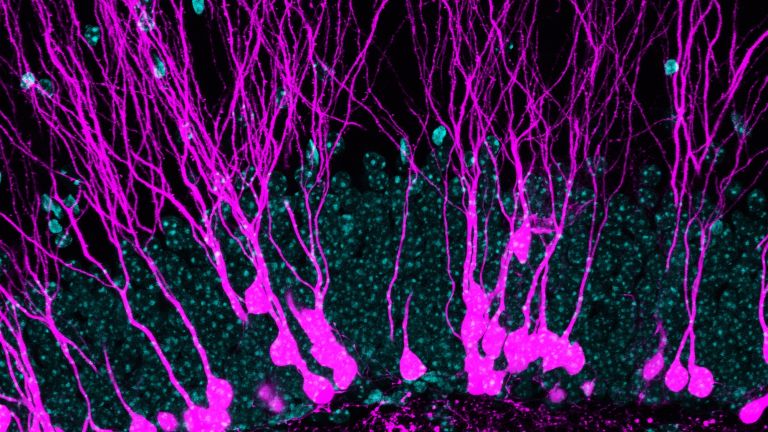

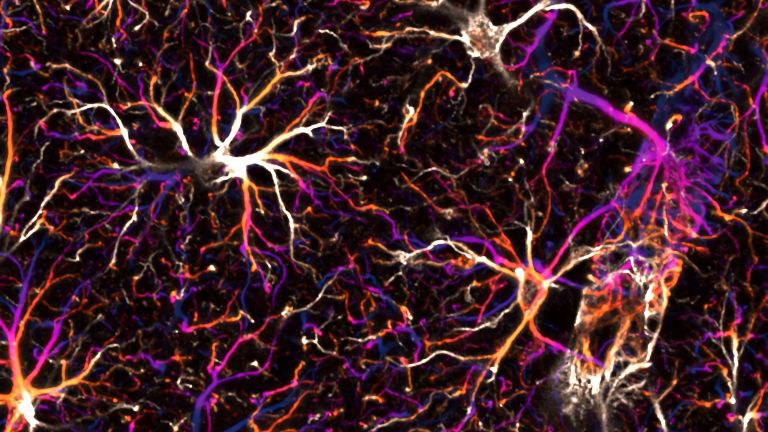

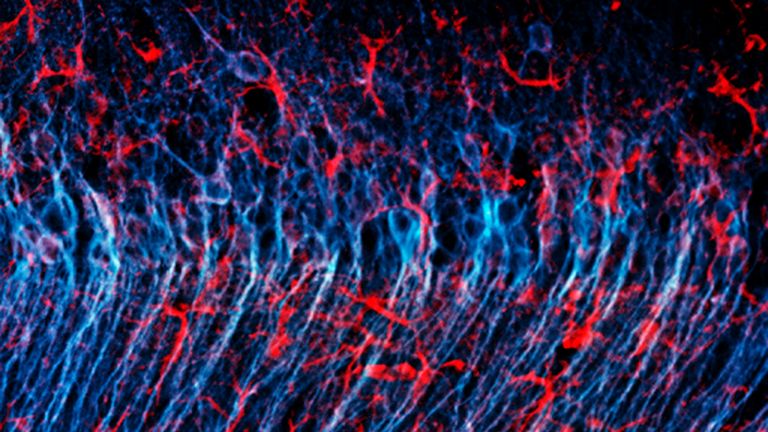

The breakthrough came from an Italian: in 1872, physiologist Camillo Golgi discovered the “black reaction” in a makeshift laboratory, a staining method that made individual neurons visible using silver nitrate. It was an incredible discovery and one that immediately sparked a new dispute. Golgi was certain that what he saw in his preparations was a connected network of cells fused together, a so-called syncytium. The Spanish physician Santiago Ramón y Cajal, who actually wanted to be a painter and who stained numerous preparations using Golgi's technique, disagreed completely. He postulated with conviction that the brain consists of individual functional units that are connected but not fused together. Ultimately, Cajal was proven right – the neuron doctrine he advocated laid the foundation for modern neurobiology.

Golgi and Cajal were honored with a joint Nobel Prize in 1906 for their achievements, however, they did not enjoy the ceremony, as the researchers were simply unable to settle their dispute.

Connecting gap

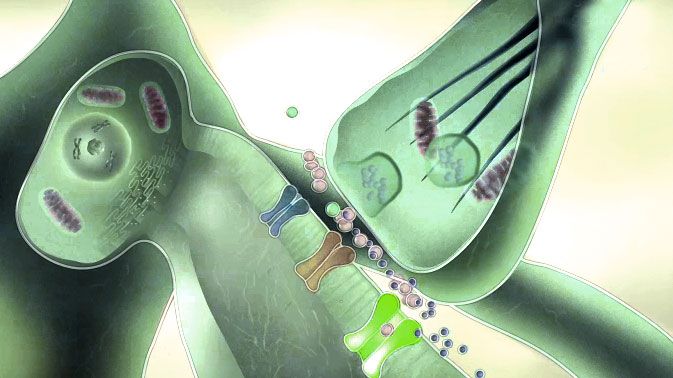

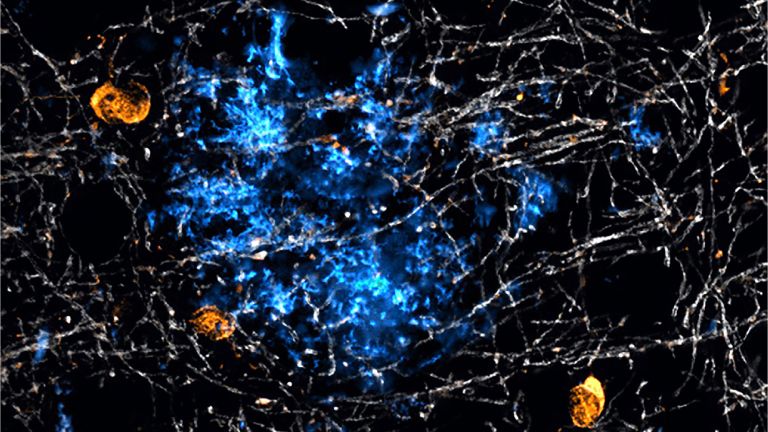

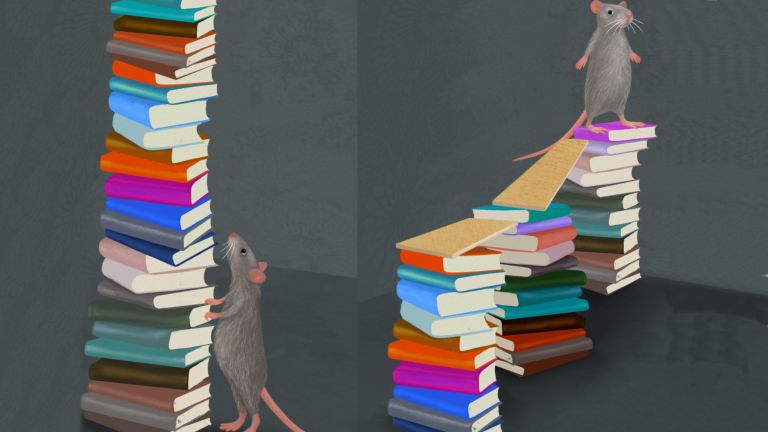

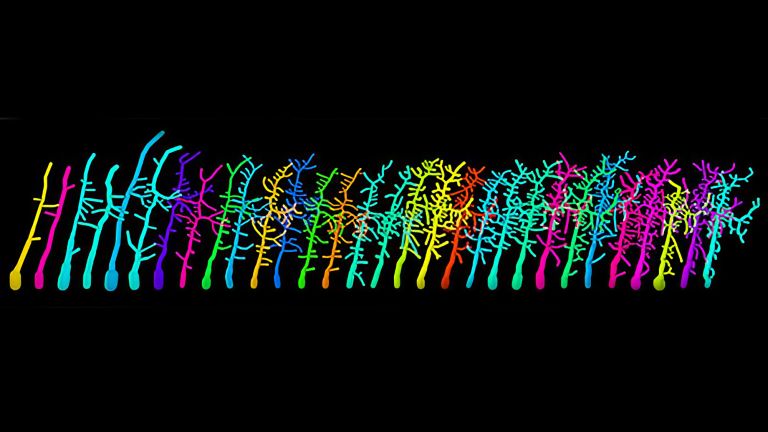

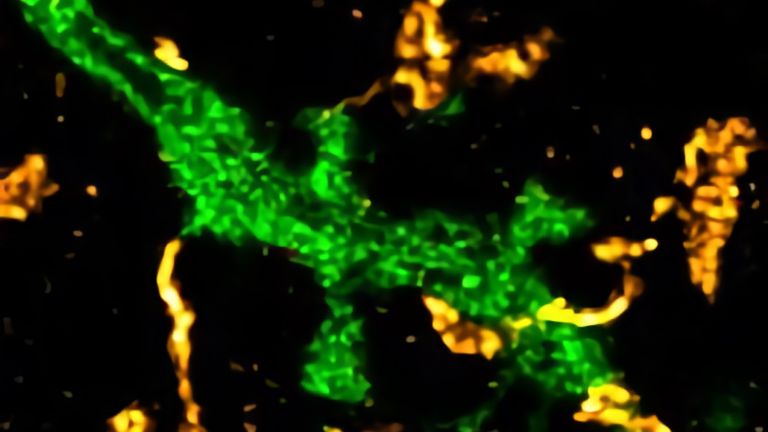

A great admirer of Cajal's work was the British neurophysiologist Charles Sherrington, who focused on the study of spinal cord reflexes. He studied certain long extensions of nerve cells, called axons, which transmit impulses to other neurons or cells. Sherrington also named the contact point between two neurons: since 1897, we call it the synapse. As we now know, synapses transmit impulses from one cell to another and are also necessary for the learning process (Synapses: interfaces of learning).

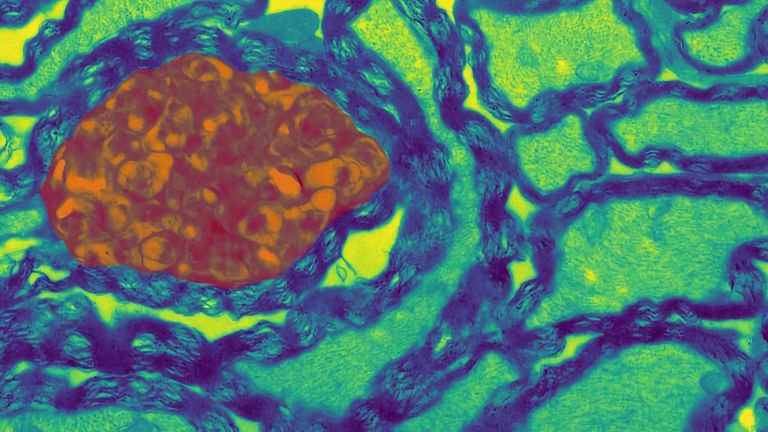

This determined the location of communication, but not its nature. This was discovered by the German pharmacologist Otto Loewi in 1921 using two frogs: he placed a still-beating frog heart in a salt solution and electrically stimulated the vagus nerve, which slowed the heartbeat. When Loewi then placed a second frog heart in the same solution, it also beat more slowly. Clearly, a chemical messenger substance in the nervous system was at work here – Loewi called it the “vagus substance,” but it is now known as acetylcholine. Loewi was awarded the Nobel Prize for his findings, however, the Nazis extorted the prize money from him. We now know that there are numerous chemical messengers.

Animal electricity

The discovery of chemical communication between nerve cells came as a surprise, as it had long been known that excitation is transmitted electrically within nerve cells. This had already been suspected by the Italian biologist Luigi Galvani: in 1786, he hung frog legs on a clothesline and observed that they twitched during thunderstorms. Galvani had discovered something he called animal electricity.

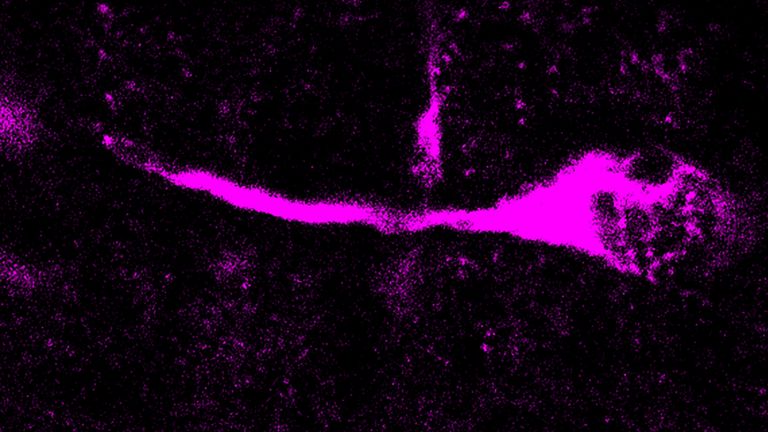

More than 50 years later, German physiologist Hermann von Helmholtz discovered that these electrical signals were not a by-product of the nerves, but carried meaningful information: the electrical impulses are something like a language of nerve cells and are transmitted via the axon.

In contrast to electricity within a copper wire, the electrical transmission of the cells was surprisingly slow: Helmholtz was able to measure that the impulses travel at just three meters per second.

Recommended articles

Action potentials

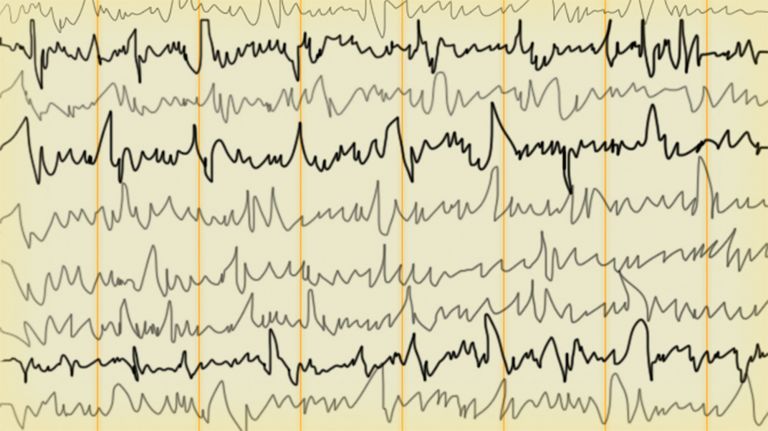

So what are the signals of neurons? British Lord Edgar Adrian devoted himself to this question from 1920 onwards. By observing the impulses of an axon using an oscilloscope, a device for measuring electrical voltages, he came to some groundbreaking conclusions. First, he saw that one electrical impulse looked exactly like the next, regardless of the intensity of the stimulus. We know this today as the all-or-nothing principle: either the neuron fires. Or it doesn't.

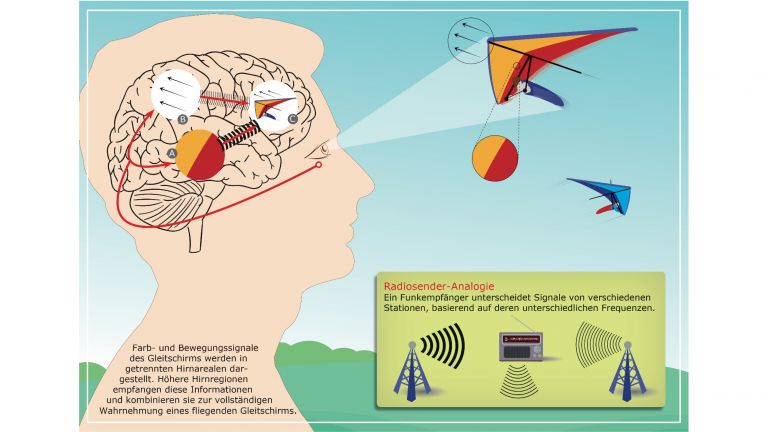

Lord Adrian made another discovery: the strength of the input stimulus was reflected in the frequency of the electrical impulses: the stronger the stimulus, the higher the firing rate. His most important discovery, however, was that the electrical impulses were also similar regardless of the message. Light falling on the retina, touch on the skin, or pain all trigger similar reactions in the nerve cells. Lord Adrian and Charles Sherrington received a joint Nobel Prize for their work in 1932 – which they accepted in a much more relaxed manner than Golgi and Cajal had done 26 years earlier.

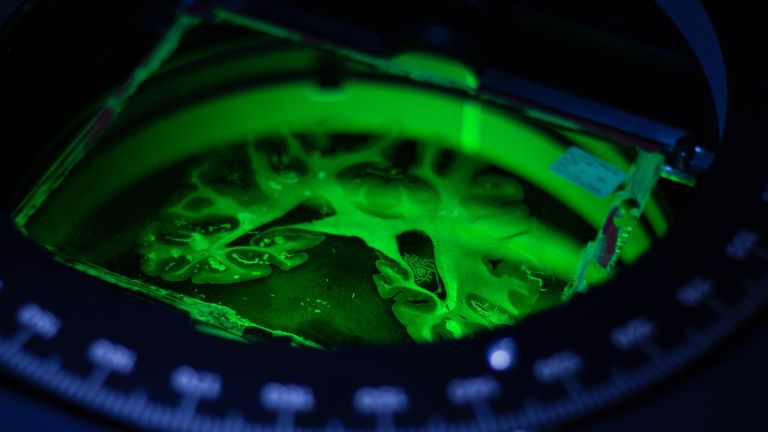

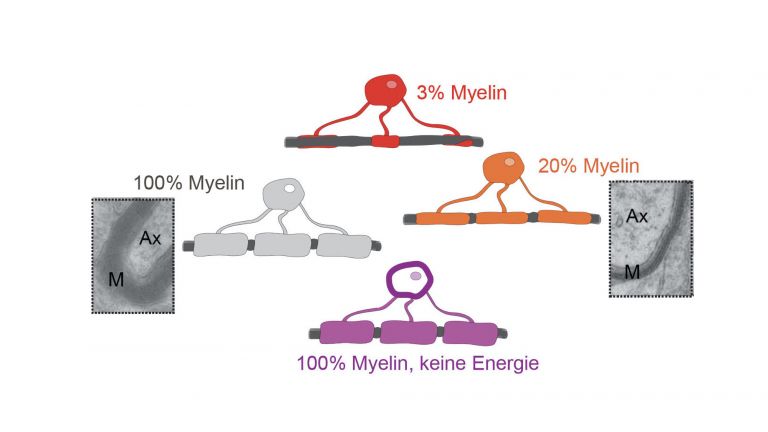

One important question remained unanswered: how electricity is generated in the cell in the first place. Helmholtz's student Julius Bernstein developed the so-called “membrane hypothesis” to answer this question. He already knew that an electrical voltage of -70 millivolts – the resting potential – is present at the membrane of an unstimulated cell. He discovered that this potential is based on the different distribution of positive and negative ions inside and outside the cell. This theory was later confirmed by Alan Hodgkin and Andrew Huxley. These two also shared a Nobel Prize: they discovered the processes of the ion channels that enable the membrane voltage to change abruptly, creating an action potential that travels through the axon to the synapse, where it triggers the chemical processes of stimulus transmission to the neighboring cell.

The missing piece

The discovery of the weak electrical potential at the dendrites, compared to the action potential, turned out to be the missing piece of the puzzle. The dendrites are, so to speak, the antennas of the neurons: they receive stimuli from neighboring cells or sensory receptors. They also send weak electrical impulses, but not outward, rather toward the cell body. Sherrington's student John Eccles, an Australian electrophysiologist, discovered with his colleagues Stephen Kuffler and Bernard Katz during World War II that these so-called postsynaptic potentials contain both inhibitory and excitatory impulses. Eccles, who later won the Nobel Prize, realized that these impulses are summed up by the nerve cell, which then either fires or does not fire.

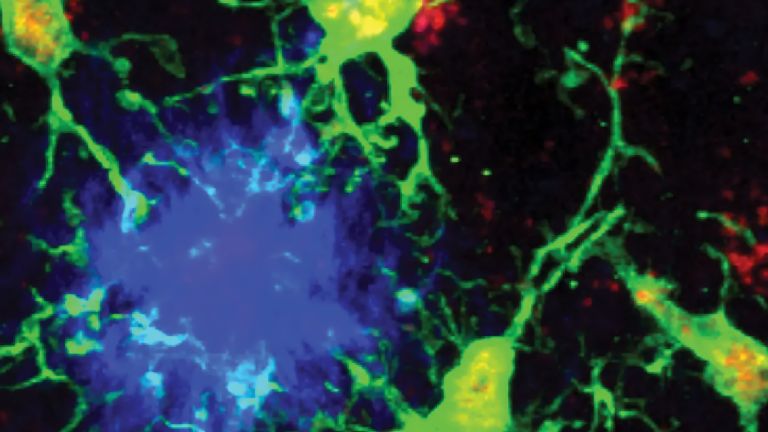

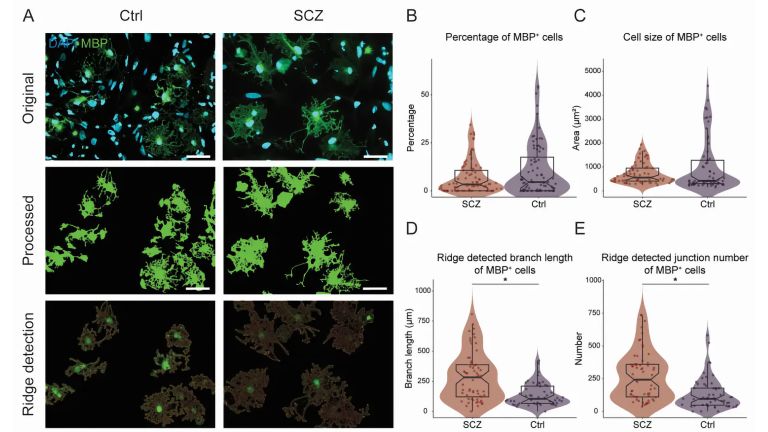

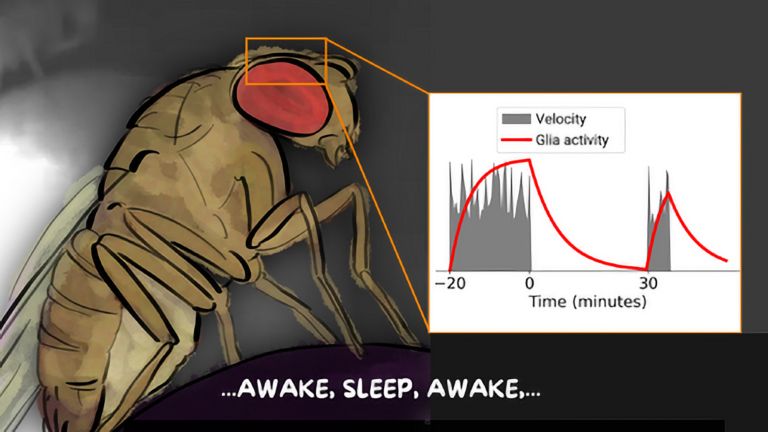

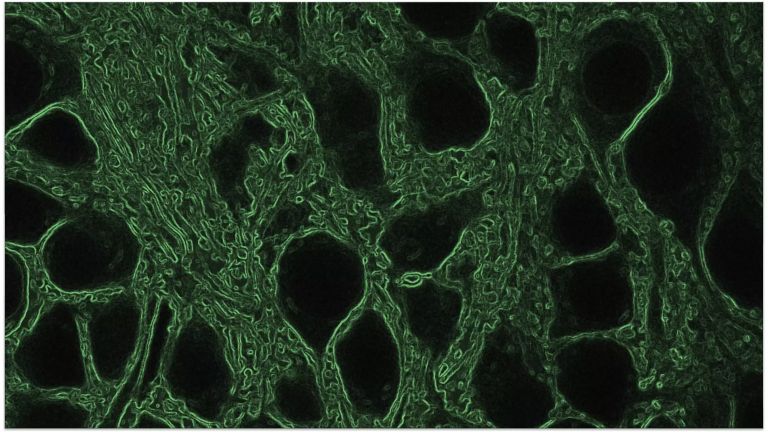

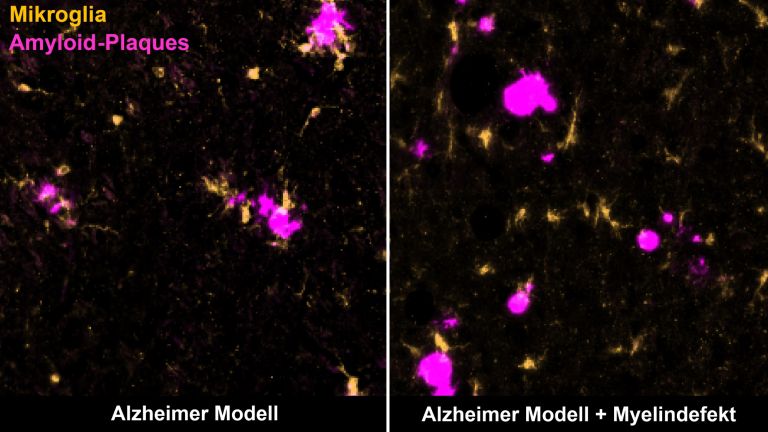

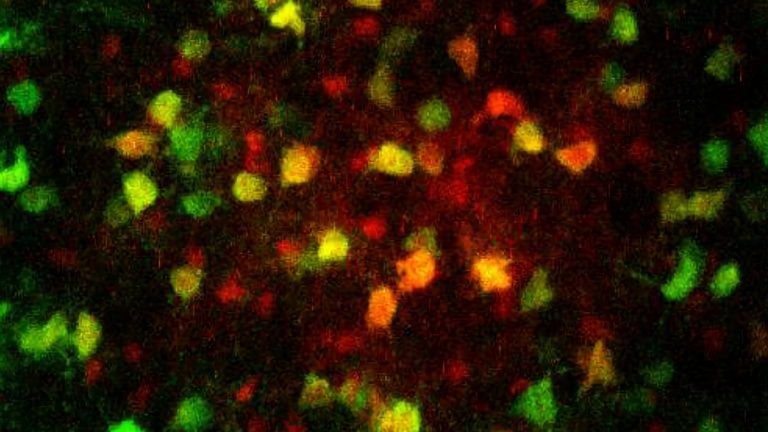

Many questions about the structure and function of nerve cells remain unanswered. As in so many fields of knowledge, brain research has shown that the more we know, the more questions we have. Researchers are now not only using molecular biology and genetic methods to search for new answers, but are also repeatedly questioning established theories. One example is the role of glial cells in the brain. Long reduced to the role of mere glue that holds the nerve cells in place, there is currently a major debate about whether they may represent a completely separate information system within the brain.

The scientific journey through the brain has only just begun.

Further reading:

- Van der Loos, H. The history of the neuron. In: H. Hyden: The Neuron. Amsterdam Elsevier, 1967, pp. 1–47.

First published on April 11, 2012

Last updated on December 22, 2023