Neurons got Rhythm

When the firing rates of one area of the brain follow a certain rhythm, this rhythm is often found in other areas of the brain as well. Some researchers believe that such synchronous oscillations are essential for conscious perception.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Jochen F. Staiger

Published: 09.10.2025

Difficulty: easy

- Researchers often find different areas of the brain whose neurons fire at the same frequency. They call this phenomenon synchronous oscillation.

- Many scientists suspect that synchronous oscillations facilitate the flow of information between different areas of the brain.

- Synchronous oscillations could also explain the binding problem. This is the question of how the brain merges different sensory impressions, which are processed simultaneously in different places in the brain, into one unified perception.

- The brain needs a very precise internal clock for many processes. Synchronous oscillations play an essential role in temporal coordination.

Oscillation

Oscillations occur when many neurons fire in synchronized, rhythmic patterns. These phased fluctuations in neural activity form the basis for measurable signals in the EEG. They reflect the coordinated processing of information in the brain.

Perception

The term describes the complex process of gathering and processing information from stimuli in the environment and from the internal states of a living being. The brain combines the information, which is perceived partly consciously and partly unconsciously, into a subjectively meaningful overall impression. If the data it receives from the sensory organs is insufficient for this, it supplements it with empirical values. This can lead to misinterpretations and explains why we succumb to optical illusions or fall for magic tricks.

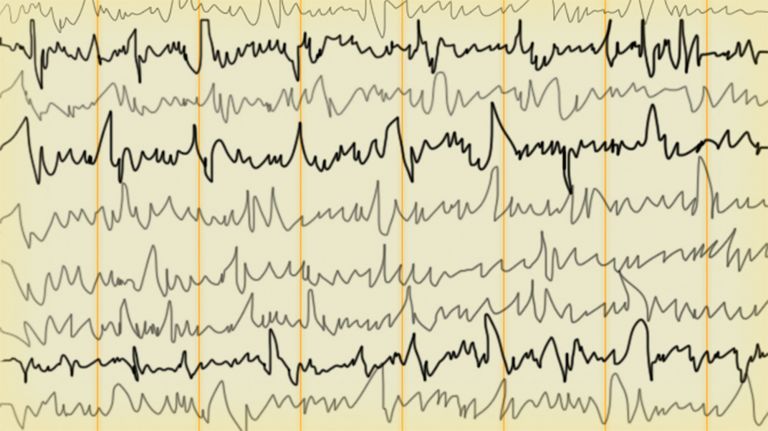

In 1924, Hans Berger was the first person to observe the activity of a human brain – at that time, directly on the brain of a patient. Today, electrodes are attached to the intact head during an electroencephalogram (EEG), which then show certain frequencies in their visualization. These are commonly divided into five frequency bands:

- Delta frequencies between 0.1 and 4 Hz (Hertz: oscillations per second) typically occur during deep sleep.

- The theta range is between 4 and 8 Hz. On the EEG, it usually appears during lighter sleep. Alpha waves between 8 and 13 Hz occur when the eyes are closed. They are associated with a relaxed state of mind.

- Beta frequencies between 13 and 30 Hz appear during wakefulness, but also during REM sleep.

- Gamma oscillations (30-100 Hz) occur during intense concentration, but also during deep meditation.

But that's not all, of course. Recent studies show, for example, that gamma oscillations are often integrated into the peaks and troughs of theta waves. Some researchers suspect that 40 Hz is the binding frequency for different sensory impulses, and they seem to be particularly important in communication between the Cortex and thalamus. Either way, there are still many unanswered questions about brain frequencies – not least of which is how the impulses we can measure on an EEG relate to the impulses of individual neurons.

Alpha waves

Neuroscientists distinguish between different types of brain waves based on their frequency. Alpha waves oscillate in the mid-frequency range between approximately 8 and 12 hertz. They occur, for example, in a relaxed waking state, such as when test subjects are tired or have their eyes closed, i.e., when there is no mental activity. In the brain, they originate primarily in the parietal lobe. They are also called "Berger's waves" Hans Berger, who first described them.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

EEG

An electroencephalogram, or EEG for short, is a recording of the brain's electrical activity (brain waves). Brain waves are measured on the surface of the head or using electrodes implanted in the brain itself. The time resolution is in the millisecond range, but the spatial resolution is very poor. The discoverer of electrical brain waves and EEG is the neurologist Hans Berger (1873−1941) from Jena.

Stefanie Liebe had been training her rhesus monkeys for almost a year, and now the animals were finally ready to start her experiment. The very first results caught her Attention. “There was no need for statistical analysis; the synchronous Oscillation was already very clear in the raw data,” recalls the neurobiologist. “I thought that was extremely cool.”

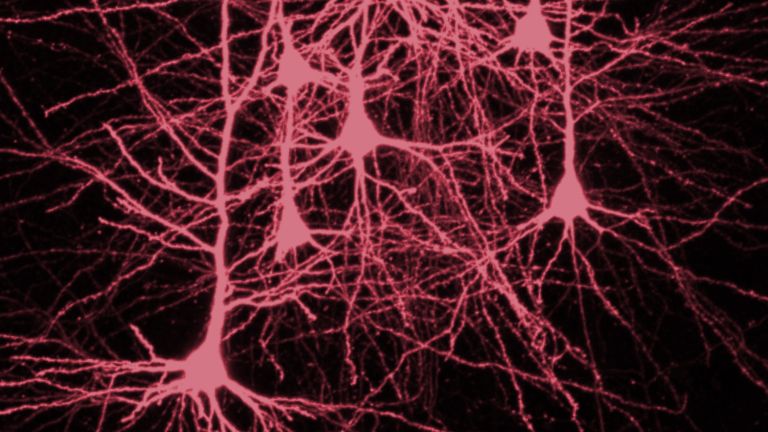

When researchers investigate processes involving multiple brain areas, they often find – as Stefanie Liebe did in her study from 2012 – synchronous oscillations, i.e., synchronized activities of entire Neuron assemblies firing in identical frequency bands. Many scientists now suspect that such recurring electrical patterns are very important for complex cognitive performance. By analyzing them, they hope to better understand how the brain works.

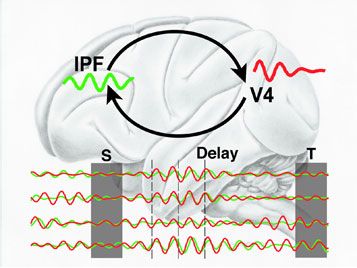

For her doctoral thesis at the Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics in Tübingen, Stefanie Liebe wanted to find out how different areas of the brain work together in Short-term memory To do this, she taught monkeys to look at images on a monitor. The animals learned that they had to press a lever as soon as an image appeared. The monitor then went black for a moment before another image appeared. The monkeys then had to decide whether this image was the same as the first one. If, for example, a butterfly was shown first, the monkeys were trained to release the lever only when another butterfly image appeared.

The researcher was now interested in what happened in the monkeys' brains when only a black screen was visible between the two images for about 30 to 50 milliseconds. This was the phase in which the animals remembered what they had seen. Using tiny electrodes, she measured the electrical voltage of individual cells at rest and how it changed after receiving impulses via the cells' synapses, known as the postsynaptic potential.

She focused on two areas of the cerebral Cortex: an area in the prefrontal cortex, which is essential for short-term working memory, and a section in the Visual cortex at the back of the brain, which processes visual information. These two areas are co-active when the monkey remembers a butterfly image – so they must communicate with each other in some way.

And indeed, the measured voltage in the visual cortex began to oscillate in a specific pattern. The area of short-term Memory oscillated in exactly the same pattern. The two areas of the brain had thus found a common rhythm across the distance; they were oscillating in unison, so to speak. Such synchronous oscillation only occurred when the monkeys were actually able to remember. If they were unable to do so, no synchronicity could be seen in the oscillations.

Attention

Attention

Attention serves as a tool for consciously perceiving internal and external stimuli. We achieve this by focusing our mental resources on a limited number of stimuli or pieces of information. While some stimuli automatically attract our attention, we can select others in a controlled manner. The brain also unconsciously processes stimuli that are not currently the focus of our attention.

Oscillation

Oscillations occur when many neurons fire in synchronized, rhythmic patterns. These phased fluctuations in neural activity form the basis for measurable signals in the EEG. They reflect the coordinated processing of information in the brain.

Neuron

A neuron is a specialized cell in the nervous system that is responsible for processing and transmitting information. It receives signals via its dendrites and transmits them via its axon. Transmission occurs electrically within the neuron and, between neurons, usually chemically via synapses.

Short-term memory

Short-term memory is a type of temporary storage in the brain where information can be retained for a few seconds to a few minutes. Its capacity is very limited, at 7±2 units of information (chunks). These can be numbers, letters, or words, for example. Today, this memory is usually considered within the framework of the working memory model, which also emphasizes the active processing of content.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Visual cortex

The visual cortex refers to the areas of the occipital lobe that are involved in processing visual information. These include the primary visual cortex and the associative visual cortices V1 to V5. According to Brodmann, the visual cortex comprises areas 17, 18, and 19.

Memory

Memory is a generic term for all types of information storage in the organism. In addition to pure retention, this also includes the absorption of information, its organization, and retrieval.

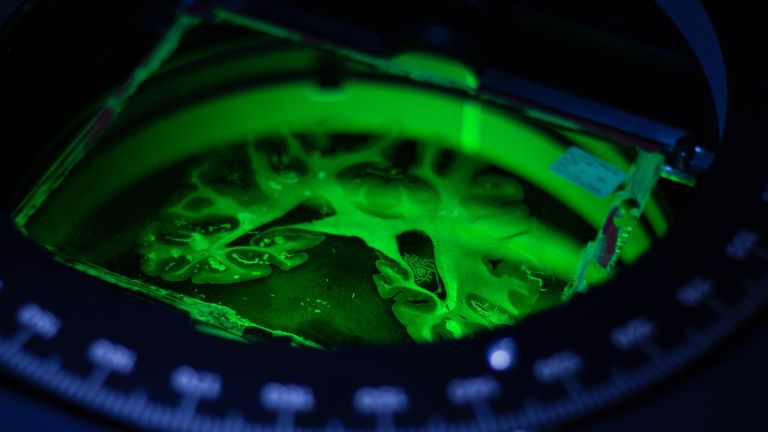

Oscillations improve information exchange

Ever since Hans Berger performed the first electroencephalograms (EEG) in 1924, doctors have known that electrical impulses in the brain constantly occur in rhythmic patterns that differ significantly between sleep and wakefulness, but also during certain perceptual processes in the brain. An EEG illustrates this in a regular sequence of zigzag lines. It measures the electrical activity in the brain using electrodes placed on the head. The device outputs the voltage changes in the form of many simultaneous wave lines. Because the electrodes are quite far away from the actual active areas of the brain, each signal can only be a very rough approximation of what is actually happening under the scalp and skull. Nevertheless, the EEG shows similar deflections in areas of the cerebral Cortex that are far apart.

In the meantime, measurements taken directly in the brain have made it possible to assign numerous oscillations to neural networks. In recent decades, researchers have developed theories to explain the phenomenon of common frequency changes.

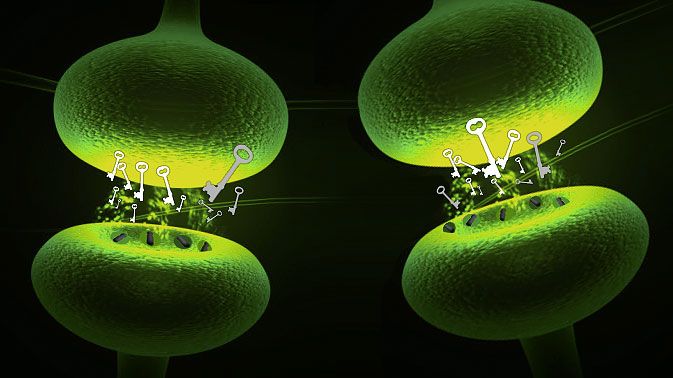

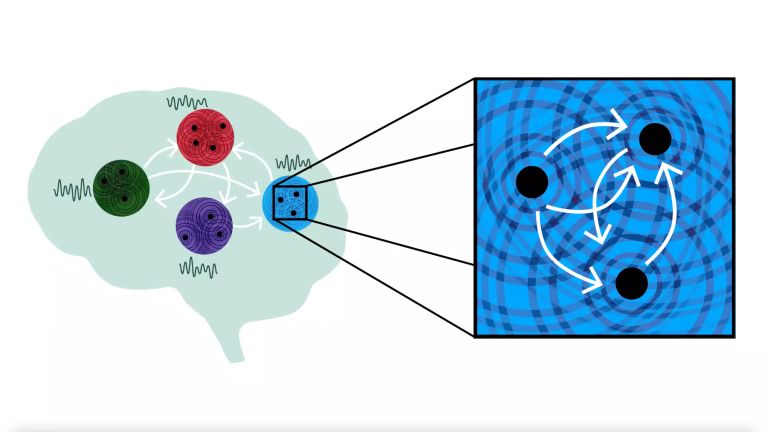

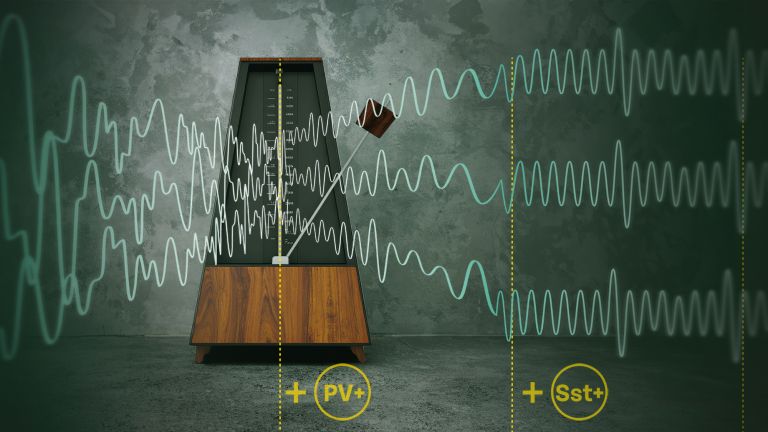

Stefanie Liebe suspects that the synchronous Oscillation she measured improves the exchange of information between brain areas. “You can imagine it as if the synchronized oscillation in both areas causes a revolving door to start turning,” says the researcher. “This allows signals to be sent back and forth more easily.” A neural network oscillates at the same rate as another so that it is particularly sensitive to its information, believes Stefanie Liebe.

EEG

An electroencephalogram, or EEG for short, is a recording of the brain's electrical activity (brain waves). Brain waves are measured on the surface of the head or using electrodes implanted in the brain itself. The time resolution is in the millisecond range, but the spatial resolution is very poor. The discoverer of electrical brain waves and EEG is the neurologist Hans Berger (1873−1941) from Jena.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Oscillation

Oscillations occur when many neurons fire in synchronized, rhythmic patterns. These phased fluctuations in neural activity form the basis for measurable signals in the EEG. They reflect the coordinated processing of information in the brain.

The binding problem

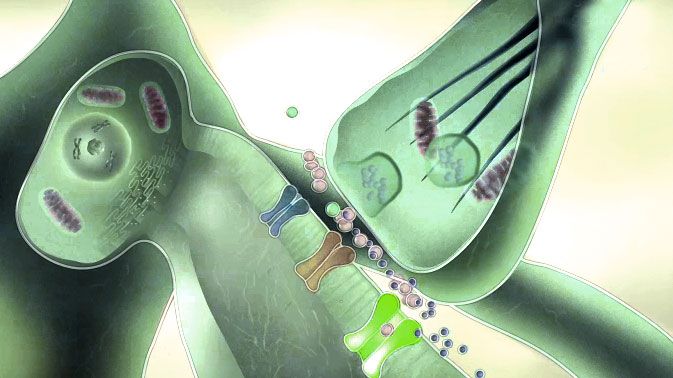

Some researchers go one step further. They believe that synchronous oscillations are not only important for effective information flow, but that they enable more complex cognitive performance in the first place. Neurobiologist Wolf Singer, now at the Ernst Strüngmann Institute (ESI) for Neuroscience in Frankfurt, measured synchronous oscillations in cats back in the 1980s. He immediately suspected that this could solve a fundamental puzzle that has been occupying brain researchers: the so-called binding problem.

It has long been known that sensory impressions are fragmented in the brain. When a person sees a red ball flying past, for example, several small neural networks in the Visual cortex become active. One area signals “something red”, another “something round”, and a third “movement from right to left”. However, people are not aware of these partial impressions; they only perceive the whole, i.e., the red ball flying past. But how does the brain connect this fragmented information to form an overall picture? Researchers summarize this question with the term “binding problem”.

Visual cortex

The visual cortex refers to the areas of the occipital lobe that are involved in processing visual information. These include the primary visual cortex and the associative visual cortices V1 to V5. According to Brodmann, the visual cortex comprises areas 17, 18, and 19.

Recommended articles

How does conscious perception arise?

Often, the binding problem is not limited to one sense, such as sight. Wolf Singer likes to use the example of a barking dog that is being petted. Many areas of the Visual system are active in this process: the size, color, and movement of the animal are analyzed. In addition, information about the texture of the fur is transmitted from the stroking hand to the brain. This information is processed in the areas of the brain responsible for the sense of touch. Because the dog is barking, the Auditory cortex is also involved in processing the auditory impression.

The person stroking the dog must also evaluate the dog's behavior, as the animal could become aggressive. This is why the limbic system, which is responsible for processing emotions, is also active. This creates an overall impression: this is a collie with long, reddish-brown, very soft fur, which barks loudly but is actually harmless. All of the information is linked together and assigned to the dog.

As a solution to the binding problem, it was initially discussed whether there might be an area in the brain that is exclusively responsible for conscious Perception. There could be, for example, a nerve cell that only fires when the collie with the soft coat barks. Despite intensive research, however, no such area of the brain – that would represent consciousness, so to speak – has been found to date. There is another catch to this theory. “If there were a separate cell for every conceivable situation, it would result in a combinatorial explosion,” says Wolf Singer. Although there are a very large number of nerve cells, there are also a very large number of possible sensory impressions, and there would have to be at least one cell for every combination of these impressions. This is not feasible, even with billions of brain cells.

Visual system

The visual system is the part of the nervous system that processes visual information. It primarily comprises the eye, the optic nerve, the optic chiasm, the optic tract, the lateral geniculate nucleus, the optic radiation, the primary visual cortex, and the visual association cortices.

Auditory cortex

The auditory cortex is a part of the temporal lobe that is involved in processing acoustic signals. It is divided into the primary and secondary auditory cortex.

Perception

The term describes the complex process of gathering and processing information from stimuli in the environment and from the internal states of a living being. The brain combines the information, which is perceived partly consciously and partly unconsciously, into a subjectively meaningful overall impression. If the data it receives from the sensory organs is insufficient for this, it supplements it with empirical values. This can lead to misinterpretations and explains why we succumb to optical illusions or fall for magic tricks.

Time as an encoding space

But how else could the binding problem be solved? When Wolf Singer measured synchronous oscillations in cats' brains almost 30 years ago, he came up with an idea. What if it is not where something takes place in the brain that is important, but when? The information “soft fur,” “loud barking,” and “reddish-brown dog” is perceived simultaneously. A pattern of brain areas specific to the situation is active and temporally related. So perhaps it is this simultaneity that is responsible for the overall impression of the barking collie. “The information is perceived uniformly. Where? Nowhere! The activity remains distributed throughout the brain,” says Wolf Singer. “Today, most brain researchers assume that the system deviates in time as an encoding space.”

For this to work, the brain must be extremely sensitive to temporal relationships. It therefore needs a very precise clock. And scientists suspect that the brain creates this clock itself through rhythmic oscillations. “You can imagine the synchronous oscillations as the pendulum strokes of a wall clock,” Wolf Singer explains. “They provide the beat so that the brain can define temporal relationships.”

Our conscious Perception may therefore not arise in a specific area of the brain, but is encoded in time with the help of oscillations. Perhaps this also applies to all other conscious thought processes. As you read these lines, you feel addressed at this moment. And according to the theory, this thought cannot be localized to one place in your brain. It arises solely from the fact that a certain pattern of brain areas is active at the same time. It is difficult to imagine, but many research findings support the theory of the temporal correlation of consciousness.

According to Wolf Singer, schizophrenic people provide a possible example of what happens when we are no longer able to do this. His research group used magnetoencephalographs (MEGs) to compare brain activity. In healthy people, the scientists observed a sharp increase in high-frequency oscillations when they showed their test subjects specific images. In schizophrenic patients, the increase was significantly lower, and there was hardly any synchronicity between different areas of the brain. Schizophrenic brains are therefore not as good at establishing temporal connections. A key symptom of this disease is that patients have fragmented thoughts; they perceive things separately that actually belong together. This distorted perception could be related to an incorrect rhythm in the brain.

Perception

The term describes the complex process of gathering and processing information from stimuli in the environment and from the internal states of a living being. The brain combines the information, which is perceived partly consciously and partly unconsciously, into a subjectively meaningful overall impression. If the data it receives from the sensory organs is insufficient for this, it supplements it with empirical values. This can lead to misinterpretations and explains why we succumb to optical illusions or fall for magic tricks.

Further reading

- Liebe S. et al: Theta coupling between V4 and prefrontal cortex predicts visual short-term Memory performance. Nature Neuroscience. 2012; 15(3):456 — 462 (zum Abstract).

- Singer, W.: Binding by synchrony. Scholarpedia. 2(12):1657 (zum Text).

- Uhlhaas PJ, Singer W: Abnormal neural oscillations and synchrony in schizophrenia. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2010; 11(2):100 — 113 (zum Abstract).

prefrontal cortex

Prefrontal cortex

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) forms the front part of the frontal lobe and is one of the brain's most important integration and control centers. It receives highly processed information from many other areas of the cortex and is responsible for planning, controlling, and flexibly adapting one's own behavior. Its central tasks include executive functions, working memory, emotion regulation, and decision-making. In addition, the PFC plays an important role in the cognitive evaluation and modulation of pain.

Memory

Memory is a generic term for all types of information storage in the organism. In addition to pure retention, this also includes the absorption of information, its organization, and retrieval.

Published on April 12, 2012

Last updated on October 9, 2025