The Human Brain Project: Review/Preview

The Human Brain Project has come to an end – and remained controversial until the end. But the HBP was more than just the initial visions of its founder. Its legacy proves this.

Published: 06.11.2023

Difficulty: easy

- The European Big Brain Project, the Human Brain Project, was launched in 2013. One billion euros in funding was on the table, but at the end, the project received 607 million euros.

- The HBP was controversial from the outset: the promises were too big, the level of knowledge too low, it would cost too much money for just one project.

- There was also internal criticism, and just two years later, a new management structure was put in place.

- Leaving aside Henry Markram's grand visions, the HBP actually achieved many of its goals, including some big ones. And it lives on in important projects, including the most detailed atlas of the human brain, the Julich Brain Atlas, and many tools for the neuroscience community.

Up to one billion euros. An enormous sum that the EU promised for a single brain research project in 2013. A flagship project, a showcase for European research excellence. It was supposed to last 10 years, and when its term had expired, the Human Brain Project came back into the media spotlight. Mostly in retrospect, but some parts will actually endure. However, we're getting ahead of ourselves, so let's start at the beginning:

The run-up: grandiose!

In the first decade of the 21st century, brain research was the undisputed pop star of science. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) constantly provided new images of area xy, which was involved in task z; consciousness was, at least in perception, on the verge of being pinned down to neural correlates; computer chips modeled on neural connections were on various drawing boards and set to revolutionize the performance of our computers. There was neuropedagogy, neuromarketing, and even neurotheology. The media omnipresence of brain research gave rise to hopes for effective therapies for major psychiatric and neurological diseases, especially dementia, which, as is still the case today, will affect more and more people in the coming decades. So it was only logical that the EU, in addition to the US and Japan, also launched its own big brain project. For the sake of completeness, China launched its own version in 2022, although its content remains unclear. Budget: $746 million.

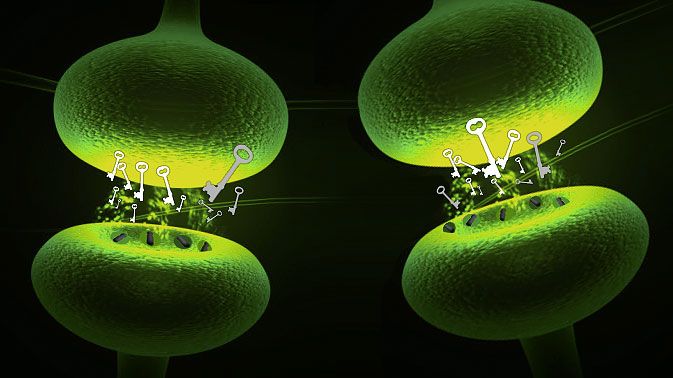

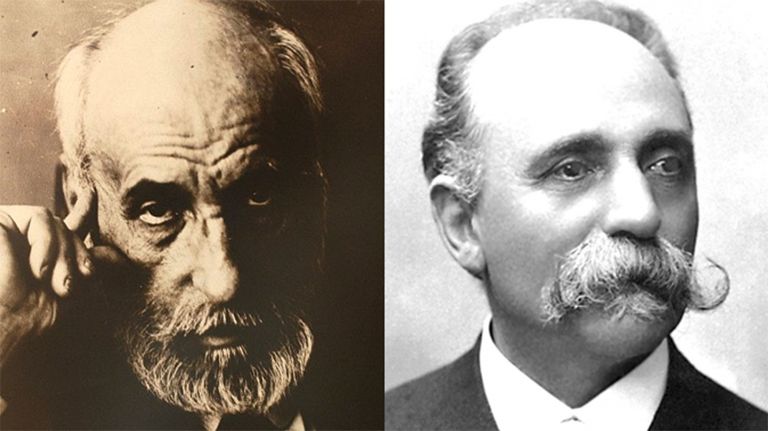

In 2013, the Human Brain Project was launched under the leadership of prominent brain researcher Henry Markram, who had already simulated the approximately 10,000 neurons of a tiny area of the rat Cortex using a supercomputer with the Blue Brain Project in Lausanne. The fact that this produced fantastic images that regularly made headlines certainly did not hurt when it came to awarding the grant. On the other hand, the fact that Markram himself had previously served as an advisor to the EU on precisely this flagship format left a certain bad Taste in the mouth. Nevertheless, Markram did indeed seem to be the right man for the job – not least thanks to his data technology experience in the Blue Brain Project.

And he presented the public with a fantastic vision: this time, the entire human brain was to be simulated. Such a simulation could, as he speculated in a TED Talk in 2009, four years before the start of the HBP, possibly even be capable of its own consciousness. In addition, neuromorphic chips were to drive the consumer industry in Europe forward. And last but not least, a platform was to be created that would collect, bundle, and make neuroscientific data generally available beyond the HBP.

This last point may sound simple but “neuroscience” is a plural term – it consists of various disciplines with different standards, different models, and different vocabularies. Above all, there is simply no unified theory, no integrated model of the brain. Markram hoped to solve this problem along the way.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is a modification of MRI that allows brain activity to be measured indirectly via regional blood flow and oxygen consumption. BOLD (blood oxygen level dependent) contrast is often used, which exploits differences in the magnetic behavior of oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood. An increase in the BOLD signal indicates increased neural activity. fMRI provides good spatial resolution and allows detailed conclusions to be drawn about the activity of specific areas of the brain, while the temporal resolution is in the range of seconds.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Taste

The sensory impression we refer to as "taste" results from the interaction between our senses of smell and taste. In terms of sensory physiology, however, "taste" is limited to the impression conveyed to us by the taste receptors on the tongue and in the surrounding mucous membranes. It is currently assumed that there are five different types of taste receptors that specialize in the taste qualities sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami. In 2005, scientists also identified possible taste receptors for fat, whose role as a distinct taste quality is still being investigated.

The start: bumpy

As grand as the vision was, its implementation was slow to get off the ground. On one hand, there was massive headwind from the scientific community itself: the promises were too unrealistic, the gaps in our knowledge of neurons, networks, and systems too large – how could we understand the entire brain when we didn't even fully understand individual circuits? A large part of the community feared that promises of this magnitude would inevitably fall flat in brain research. When we asked researchers in Göttingen for their opinion at the 2013 annual meeting of the German Neuroscience Society, skepticism prevailed by far. There was also a very practical reason: a large number of brain researchers feared that this major project would mean that research funds would no longer be available for smaller projects.

But there was also discontent within the HBP itself: since third-party funding was not as generous as expected, cuts had to be made from the outset. This led to a collision between the reality of what was feasible and the promise of large-scale simulation. Many strong leaders were active in both administration – such as the allocation of funds – and research led to friction. Markram proved to be a less than talented diplomat, and as early as 2014, there was an open letter that heavily criticized both the leadership and decision-making in the HBP. The arbitration commission that was subsequently appointed confirmed most of the allegations. Markram was voted out and the HBP has been headed by Jülich neuroanatomist Katrin Amunts since 2016.

Phase II

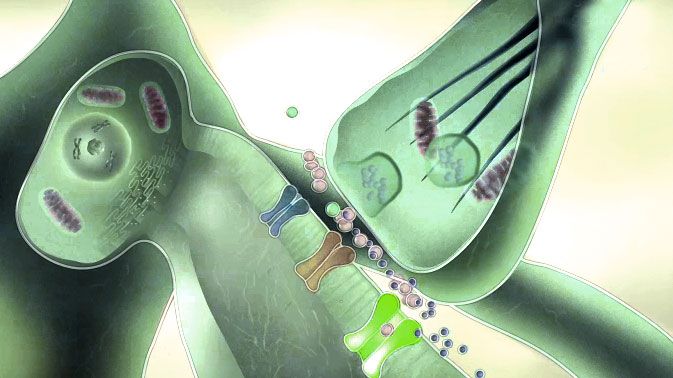

With Katrin Amunts, the HBP got back on its feet, strategically as well as structurally, with a calmer and more serious approach. Data technology came to the fore, and simulation became one tool among many, albeit still in a central position. At the same time, cognitive neuroscience was given greater consideration and the HBP was expanded to include four new projects. This was because the focus was still on the human brain, and the elementary molecular and cellular levels cannot explain the processes of large networks, such as language. This requires research projects that investigate the function of the brain across all scales – a major challenge for the future.

It was still necessary to bring together the many different approaches and disciplines of brain research and to find a common language with the other disciplines involved: medicine, computer science, and physics. Even if a unified theory is still a long way off, a common model can only emerge if data, methods, and models can be seamlessly integrated – another enormous challenge that has now been solved quite well, at least within the HBP.

Recommended articles

The legacy

From the above-mentioned TED Talk from 2009, one might think that the project had failed miserably. However, if we compare Markram's TED Talk with the actual goals of the project at its launch – to create the technical foundations for a new model of IT-supported brain research, to promote the integration of data and knowledge from various disciplines, and to catalyze a joint effort – many of these goals have actually been achieved. And as for the TED Talks: The US BRAIN Initiative, announced by then-President Barack Obama just days after the HBP, also set the bar unrealistically high: The flow of “every spike in every neuron” was to be mapped. In retrospect, this idea is just as naive. On the other hand, Cambridge neuroscientist Timothy O'Leary explains in a summary article in Nature that without such naivety – or, more precisely, a “ridiculously ambitious goal” – the HBP would probably never have been launched.

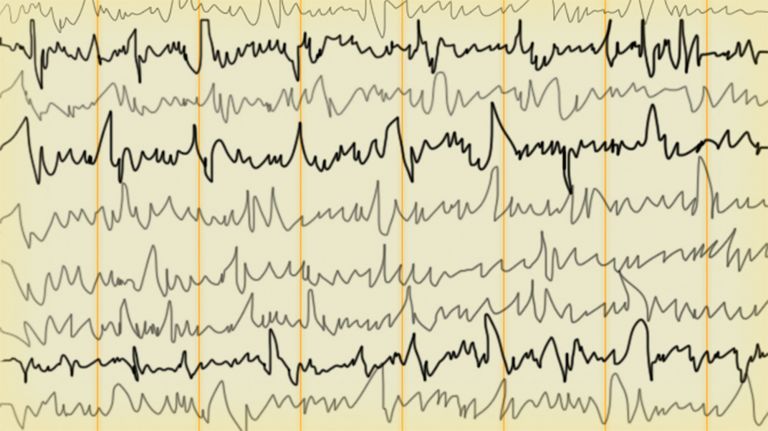

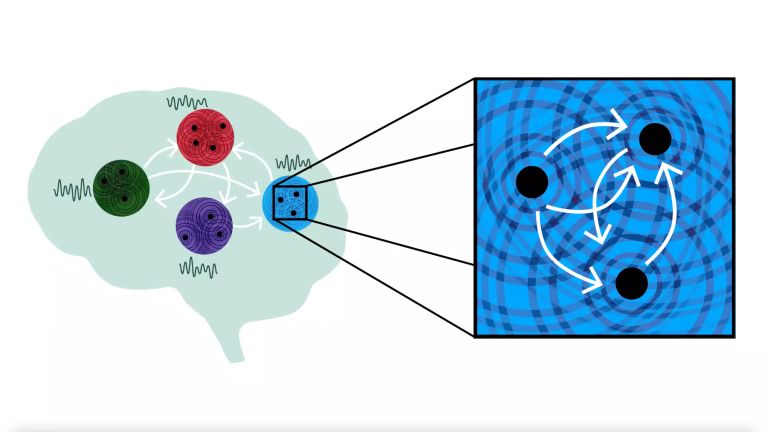

Opinions differ as to whether it was a success or not. However, the reorientation has led to the launch of projects that go beyond the HBP, not only carrying its DNA into the next phase, but also offering it in a future-proof form under the EBRAINS platform. This is a well-stocked toolbox for all neuroscientists,and some of the tools are real eye-catchers. One example is The Virtual Brain, a simulation platform developed by Viktor Jirsa and Fabrice Bartolomei, which is currently being tested by surgeons in a large-scale clinical study to prepare for operations on epilepsy patients. Fed with patient data, it can help improve surgical planning. In severe cases of epilepsy, the source of the pathological brain activity – the seizure focus – must be surgically removed, so precise planning is extremely important. Too much or too little tissue removed can determine the success of the procedure.

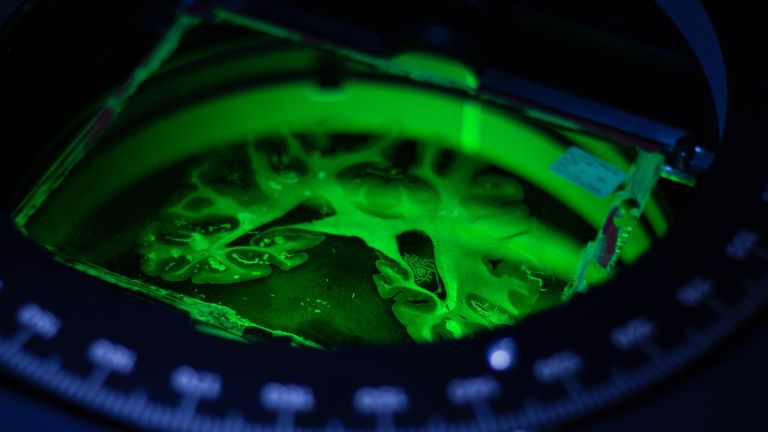

Another legacy of the HBP comes directly from Katrin Amunts: the Julich Brain Atlas, created from 24,000 wafer-thin slices of 23 human brains that were digitally reassembled – more comprehensive and detailed than anything that came before. With it, she continues her profession as director of the Cécile and Oskar Vogt Institute for Brain Research at the University of Düsseldorf. Similar to how the Vogts, with their famous colleague Korbinian Brodmann, developed maps of the Cortex and identified individual areas based on histological differences as early as 1909, Amunts has developed something she describes as “Google Maps” for the brain: On the one hand, it is possible to delve into the depths of Gene expression and molecules from the cellular level, but on the other hand, networks and areas are within reach.

Almost more important is the openness of the EBRAINS platform: all data in the Julich Brain Atlas is publicly accessible. Researchers can upload their data and even their own scripts that process this data. This is not “citizen science,” but rather “community science,” yet in any case open to expansion – and it is precisely this general comparability and usability of its results, based on professional data management, that brain research needs. In addition to functional, genetic, and molecular data, metadata such as author and DOI are also recorded. The idea is to collect data from the broad community of brain researchers and, in doing so, to develop the standards that are lacking across the various disciplines.

Such an atlas already has practical value, but for many laboratories, the offer of direct access to supercomputers via EBRAINS, enabling them to complete data-intensive tasks much faster than would be possible in their own laboratories, is likely to be no less attractive.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Gene

Information unit on DNA. Specialized enzymes translate the core component of a gene into ribonucleic acid (RNA). While some ribonucleic acids perform important functions in the cell themselves, others specify the order in which the cell should assemble individual amino acids into a specific protein. The gene thus provides the code for this protein. In addition, a gene also includes regulatory elements on the DNA that ensure that the gene is read exactly when the cell or organism actually needs its product.

The hope

Looking at this legacy, there is a certain irony: in recent years, the HBP has created the foundation for what it needed at the beginning. For all its mistakes and exaggerations, Henry Markram's vision was not entirely wrong: a large community, a common language, a viable theory of the brain, a common platform – nothing less is needed to decode the brain. In addition, we need to look beyond the purely neural – keyword glial cells; or the heart-brain- and gut-brain systems, but that might be setting the bar a little too high. It is to be hoped that the community will not be deterred by the past and will take advantage of EBRAINS' offerings, filling and further developing them.