Neurotransmitters: Messenger Molecules in the Brain

When people talk about them, they are often referred to as “happy hormones”: neurotransmitters such as serotonin and dopamine play a key role in communication between neurons.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Jochen F. Staiger

Published: 05.08.2025

Difficulty: easy

- Most synapses function on the basis of biochemical signal transmission via neurotransmitters.

- The neurotransmitters are released presynaptically by the “sender” and dock postsynaptically to specific receptors on receiving neurons, where they have an excitatory or inhibitory effect.

- Each Neurotransmitter defines a system – a specific molecular machinery responsible for the synthesis, release, effect, reuptake, and degradation of the transmitter, such as the dopaminergic system or the cholinergic system.

- Particularly rapid communication is usually based on the amino acid neurotransmitters glutamate, GABA, or glycine, which activate ion channels in the receiving cell.

- Amino acid transmitters such as the “happiness hormones”, Serotonin and dopamine, are also of outstanding importance due to their longer-term effect of modulating the entire system.

- Peptides known as hormones, such as oxytocin, angiotensin II, and somatostatin, can also be released at various synapses in the central nervous system.

excitatory

Exciting synapses are described as excitatory when they depolarize the subsequent cell membrane and can thus lead to the formation of an action potential. An excitatory effect is usually produced by an exciting transmitter (messenger substance), such as glutamate. The opposite is an inhibitory synapse.

Neurotransmitter

A neurotransmitter is a chemical messenger, an intermediary substance. It is released by the sender neuron at the sites of cell-cell communication and has an excitatory or inhibitory effect on the receiver neuron.

cholinergic

Cholinergic neurons produce acetylcholine (an important neurotransmitter in the brain), and cholinergic synapses use it to transmit signals.

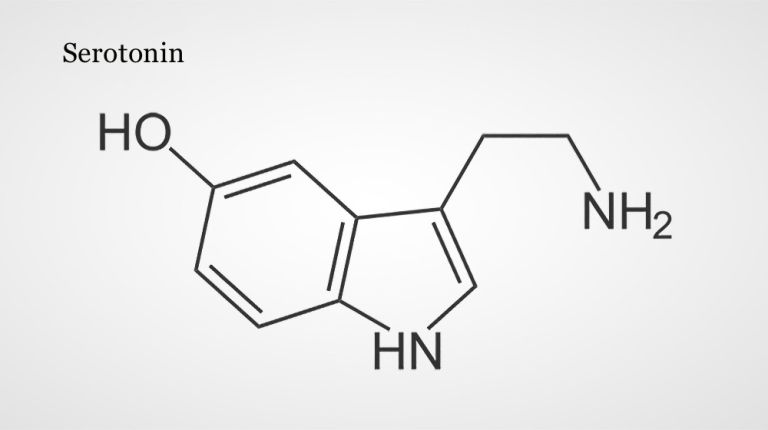

Serotonin

A neurotransmitter that acts as a messenger in the transmission of information between neurons at their synapses. It is primarily produced in the raphe nuclei of the brain stem and plays a key role in sleep and alertness, as well as emotional well-being.

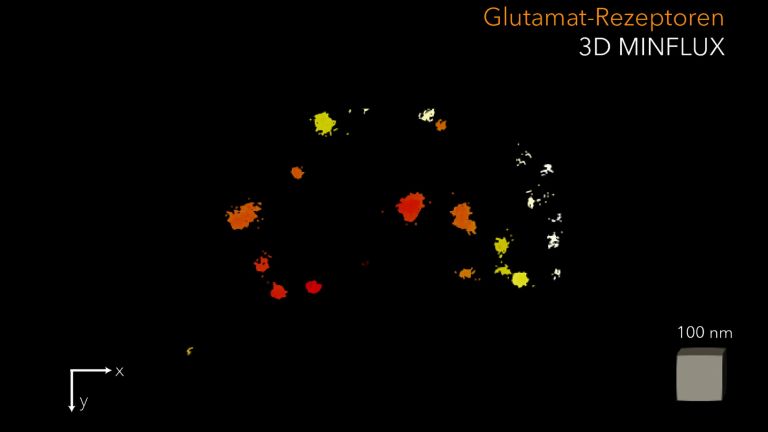

Each Neurotransmitter has its own specific receptors – and usually many different ones, known as subtypes. In laboratory tests, they can be distinguished, for example, by how they react to other chemical compounds. There are three subtypes of Glutamate receptors. One of them can be activated not only by glutamate but also by a substance called “AMPA”, another by the modified amino acid NMDA, and the third by so-called kainic acid. Such compounds, to which the Receptor subtypes respond, are also called agonists. In contrast, antagonists block a receptor instead of activating it.

Receptors can also be distinguished by their mechanism of action. All glutamate receptors, whether AMPA, NMDA, or kainate receptors, directly open an Ion channel in the postsynaptic membrane when activated (ionotropic receptors). In contrast, the numerous metabotropic receptors trigger more complex biochemical processes in the cell, which modulate signal processing in the longer term.

Neurotransmitter

A neurotransmitter is a chemical messenger, an intermediary substance. It is released by the sender neuron at the sites of cell-cell communication and has an excitatory or inhibitory effect on the receiver neuron.

Glutamate

Glutamate is an amino acid and the most important excitatory neurotransmitter, which acts as a messenger substance in the transmission of information between neurons at their synapses.

Receptor

A receptor is a protein, usually located in the cell membrane or inside the cell, that recognizes a specific external signal (e.g., a neurotransmitter, hormone, or other ligand) and causes the cell to trigger a defined response. Depending on the type of receptor, this response can be excitatory, inhibitory, or modulatory.

Ion channel

Ion channels are embedded in the cell membrane of nerve cells and all other cells in the body. They enable electrically charged particles, known as ions, to pass through the cell membrane into and out of the cell. They can therefore influence the membrane potential of a cell and trigger an action potential. A large number of different ion channels are known. Normally, ion channels have a specific permeability for only one type of ion, e.g., sodium ions or potassium ions. These are referred to as sodium channels or potassium channels, respectively.

Most of the neurotransmitters known today can be classified into three substance classes. The three most common transmitters, glutamate, GABA, and glycine, are amino acids – small building blocks of protein molecules that are found throughout the body. Serotonin, dopamine, and other transmitters belong to the amines, which are formed from amino acids through enzymatic reactions. The third group consists of neuropeptides, of which more than 50 have been discovered to date. Peptides are short chain molecules made up of amino acids and can be synthesized by cells in the same way as proteins (long amino acid chains) according to genetically coded blueprints. In addition, there are neurotransmitters that do not fit into this scheme: For example, dissolved nitric oxide or the molecule ATP are also involved in neuronal communication as messenger substances.

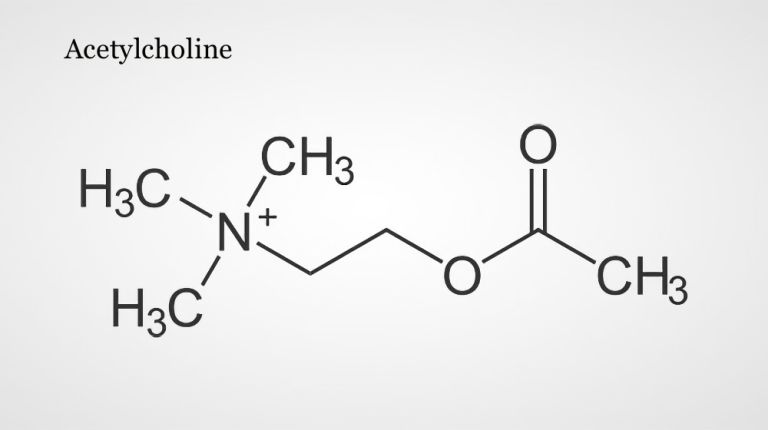

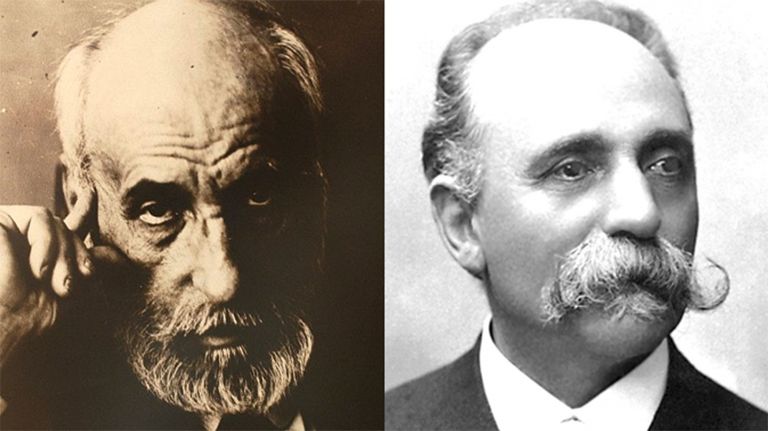

In the 19th century, the discovery of the synaptic cleft provided evidence that signal transmission between nerve cells could occur chemically. However, the high speed of transmission led many researchers to believe in an electrical mechanism. Not so Otto Loewi. The pharmacologist, who was born in Frankfurt and later emigrated to the USA, said that one night he dreamed of the decisive experiment, woke up, and immediately put it into practice with success. To do this, Loewi placed a still-beating frog heart in a saline solution and electrically stimulated the vagus nerve, which, as expected, slowed the heartbeat. When Loewi then placed a second frog heart in the same solution, it also beat more slowly. So there had to be a “vagus substance” that mediates neural communication. As it later turned out, this substance is the Neurotransmitter acetylcholine.

Neurotransmitter

A neurotransmitter is a chemical messenger, an intermediary substance. It is released by the sender neuron at the sites of cell-cell communication and has an excitatory or inhibitory effect on the receiver neuron.

Acetylcholine

Acetylcholine is one of the most important neurotransmitters in the nervous system. In the central nervous system, it is involved in attention, learning, and memory; in the peripheral nervous system, it transmits excitation from nerves to muscles at the neuromuscular end plates and controls processes of the autonomic nervous system, i.e., the sympathetic and parasympathetic parts. Areas in which acetylcholine acts as a messenger substance are called cholinergic. It was the first neurotransmitter to be discovered, identified in 1921 by Otto Loewi in the heart of a frog.

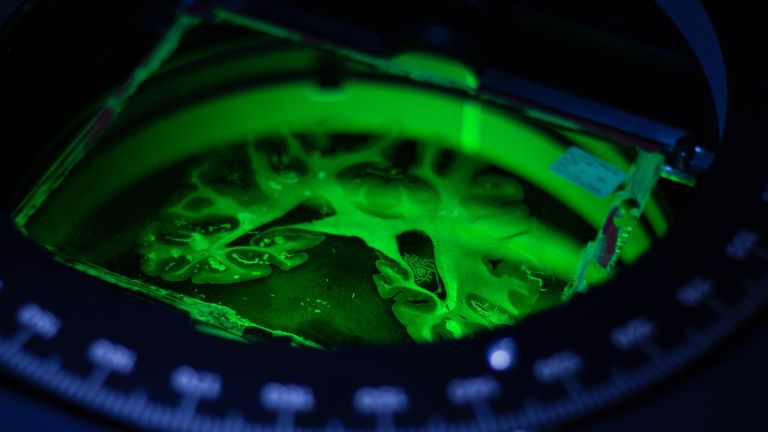

Information processing in the brain depends on networks of nerve cells communicating with each other via synapses. But how exactly do the cells communicate with each other? For a long time, researchers assumed that an electrical current flows between the cells – an obvious hypothesis, since information is primarily transmitted within a single nerve cell as an electrical action potential.

In fact, there are those so-called electrical synapses that connect neurons, known as gap junctions. However, they are in the minority in our nervous system. Most synapses communicate with each other chemically – a method that was impressively demonstrated 1921 by the scientist Otto Loewi (see info box). Since then, many of his successors have studied the chemical transmission of electrical excitation at synapses and discovered that they offer far more diverse possibilities than a simple electrical contact point.

The messenger substances that transmit information at chemical synapses are called neurotransmitters. Through painstaking puzzle work, scientists have been able to identify dozens of these substances to date. They can be divided into different classes (see info box). The best known are probably Serotonin and dopamine, both of which are also considered “happiness hormones” – more on that later. However, other neurotransmitters are crucial in the majority of chemical synapses: in most excitatory synapses, Glutamate is the carrier of information, while in inhibitory synapses it is GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) or glycine.

Serotonin

A neurotransmitter that acts as a messenger in the transmission of information between neurons at their synapses. It is primarily produced in the raphe nuclei of the brain stem and plays a key role in sleep and alertness, as well as emotional well-being.

excitatory

Exciting synapses are described as excitatory when they depolarize the subsequent cell membrane and can thus lead to the formation of an action potential. An excitatory effect is usually produced by an exciting transmitter (messenger substance), such as glutamate. The opposite is an inhibitory synapse.

Glutamate

Glutamate is an amino acid and the most important excitatory neurotransmitter, which acts as a messenger substance in the transmission of information between neurons at their synapses.

GABA

GABA is an amino acid and the most important inhibitory neurotransmitter, which acts as a messenger in the transmission of information between neurons at their synapses.

Each transmitter has its own biochemical machinery

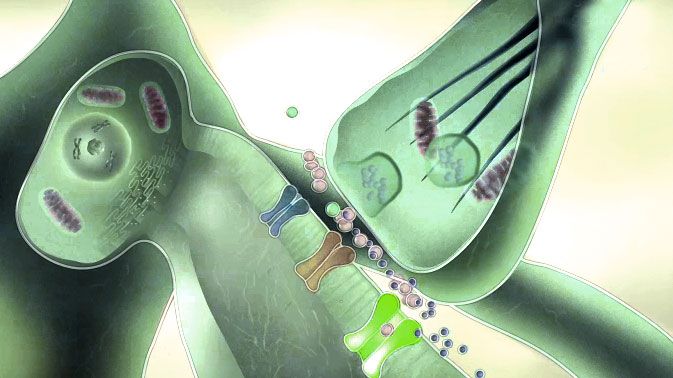

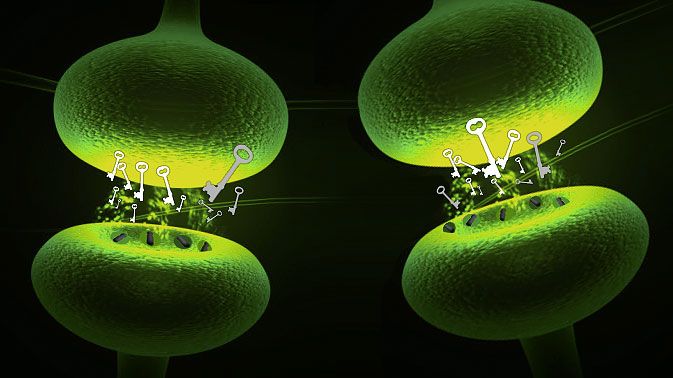

Neurotransmitters usually migrate from the presynapse of the sending Neuron across a synaptic cleft to a postsynaptic membrane, which may be located on the axon, dendrites, or cell body of another receiving nerve cell. They are produced on the output side, i.e., in the presynapse, and stored in small vesicles. When an Action potential arrives, the vesicles empty into the synaptic cleft. At the postsynaptic membrane, the transmitter molecules fit to specific Receptor proteins like a key in a lock. There they can have an excitatory or inhibitory effect, depending on the transmitter itself and, in many cases, on the specific receptor type (see info box). In any case, this creates an input that the postsynaptic neuron can process together with signals coming in from elsewhere.

After signal transmission, it's time to clean up: in order for the Synapse to become functional again, the transmitter molecules must disappear from the gap. At least for those substances that are responsible for rapid communication, the presynaptic membrane helps: transport proteins ensure that the transmitter is reabsorbed into the neuron. There it is either recycled or broken down.

Each transmitter, therefore, needs a specially tailored mechanism to ensure that synthesis, release, effect, and reuptake function smoothly. Many drugs, medications, and even poisons interfere with this complex biochemical cycle by activating or blocking transmitter receptors or inhibiting reuptake.

Neuron

A neuron is a specialized cell in the nervous system that is responsible for processing and transmitting information. It receives signals via its dendrites and transmits them via its axon. Transmission occurs electrically within the neuron and, between neurons, usually chemically via synapses.

Action potential

In excitable cells (e.g., neurons or muscle cells), very rapid changes in electrical potential occur across the cell membrane. This event is the basis for signal conduction along the axon of the nerve cell. The action potential continues along the cell membrane and, according to the all-or-nothing principle, only occurs when the cell has been sufficiently excited.

Receptor

A receptor is a protein, usually located in the cell membrane or inside the cell, that recognizes a specific external signal (e.g., a neurotransmitter, hormone, or other ligand) and causes the cell to trigger a defined response. Depending on the type of receptor, this response can be excitatory, inhibitory, or modulatory.

excitatory

Exciting synapses are described as excitatory when they depolarize the subsequent cell membrane and can thus lead to the formation of an action potential. An excitatory effect is usually produced by an exciting transmitter (messenger substance), such as glutamate. The opposite is an inhibitory synapse.

Synapse

A synapse is a connection between two neurons and serves as a means of communication between them. It consists of a presynaptic region – the terminal button of the sender neuron – and a postsynaptic region – the region of the receiver neuron with its receptors. Between them lies the synaptic cleft.

Three important neurotransmitter systems

Since nerve cells specialize in one or a few transmitters, messenger substances can often be assigned to specific Neuron networks. Particularly well-known and significant examples of such Neurotransmitter systems are the cholinergic system around the transmitter acetylcholine, the serotonergic system with the messenger substance serotonin, and, analogously, the dopaminergic system with the neurotransmitter Dopamine. These three will be discussed in more detail below.

A special feature of these three networks is that they have relatively small areas of origin, meaning that they are only produced by specific, narrowly defined groups of neurons. However, their influence extends to over 100,000 synapses and more per participating neuron in many different areas of the brain. In addition, acetylcholine, serotonin, and dopamine have a slower, longer-lasting effect than glutamate, for example, because they are not only released in a single synapse, but diffused in a larger area (so-called volume transmission). They therefore play a special role in regulating comprehensive states such as sleep, wakefulness, or mood. A textbook therefore compares these networks, known as “diffuse modulatory systems”, to the treble and bass controls on a radio: although they cannot change the vocals and melody, they can drastically influence their effect.

Neuron

A neuron is a specialized cell in the nervous system that is responsible for processing and transmitting information. It receives signals via its dendrites and transmits them via its axon. Transmission occurs electrically within the neuron and, between neurons, usually chemically via synapses.

Neurotransmitter

A neurotransmitter is a chemical messenger, an intermediary substance. It is released by the sender neuron at the sites of cell-cell communication and has an excitatory or inhibitory effect on the receiver neuron.

cholinergic

Cholinergic neurons produce acetylcholine (an important neurotransmitter in the brain), and cholinergic synapses use it to transmit signals.

Dopamine

Dopamine is an important neurotransmitter in the central nervous system that belongs to the catecholamine group. It plays a role in motor function, motivation, emotion, and cognitive processes. Disruptions in the function of this transmitter play a role in many brain disorders, such as schizophrenia, depression, Parkinson's disease, and substance dependence.

Acetylcholine: a multi-talented substance

One system innervates the hippocampus, neocortex, and Olfactory bulb from the base of the Cerebrum (between and below the Basal ganglia These cells are among the first to die in Alzheimer's disease The extent to which there is a connection to the disease beyond this is unclear. However, among the approved Alzheimer's drugs, which are intended to at least delay the loss of mental abilities, there are active ingredients that slow down the breakdown of acetylcholine in the brain. The second system consists of cells in the Pons and Tegmentum of the Midbrain. It acts primarily on the thalamus, but also strongly on the cerebrum.

Cholinergic neurons are involved in controlling Attention and brain excitability during sleep and wakefulness rhythms. Animal experiments have shown that acetylcholine promotes the transmission of sensory stimuli from the thalamus to the relevant regions of the Cortex. It also appears to play a crucial role in Plasticity and learning.

Acetylcholine

Acetylcholine is one of the most important neurotransmitters in the nervous system. In the central nervous system, it is involved in attention, learning, and memory; in the peripheral nervous system, it transmits excitation from nerves to muscles at the neuromuscular end plates and controls processes of the autonomic nervous system, i.e., the sympathetic and parasympathetic parts. Areas in which acetylcholine acts as a messenger substance are called cholinergic. It was the first neurotransmitter to be discovered, identified in 1921 by Otto Loewi in the heart of a frog.

Neurotransmitter

A neurotransmitter is a chemical messenger, an intermediary substance. It is released by the sender neuron at the sites of cell-cell communication and has an excitatory or inhibitory effect on the receiver neuron.

Autonomic nervous system

The part of the nervous system that primarily controls unconscious vital functions such as breathing, heartbeat, and blood pressure. The autonomic nervous system is divided into the sympathetic nervous system, which is active in performance and stress situations, and the parasympathetic nervous system, which is active during rest and recovery phases. In some cases, the enteric nervous system, which is responsible for gastrointestinal functions, is also considered part of the autonomic nervous system.

cholinergic

Cholinergic neurons produce acetylcholine (an important neurotransmitter in the brain), and cholinergic synapses use it to transmit signals.

Olfactory bulb

bulbus olfactorius

The anterior part of the brain that transmits information from the olfactory nerves to the olfactory brain (rhinencephalon) after initial processing via the olfactory tract.

Cerebrum

telencephalon

The cerebrum comprises the cerebral cortex (gray matter), the nerve fibers (white matter), and the basal ganglia. It is the largest part of the brain. The cortex can be divided into four cortical areas: the temporal lobe, frontal lobe, occipital lobe, and parietal lobe.

Its functions include the coordination of perception, motivation, learning, and thinking.

Basal ganglia

Nuclei basales

The basal ganglia are a group of subcortical nuclei (located beneath the cerebral cortex) in the telencephalon. The basal ganglia include the globus pallidus and the striatum, and, depending on the author, other structures such as the substantia nigra and the subthalamic nucleus. The basal ganglia are primarily associated with voluntary motor function, but they also influence motivation, learning, and emotion.

Alzheimer's disease

Morbus Alzheimer

Alzheimer's disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by cortical atrophy, nerve cell loss, synapse loss, and deposits of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, leading to dementia and loss of function. Early symptoms include memory problems, speech disorders, executive deficits, depressive moods, and subtle personality changes. As the disease progresses, global cognitive impairment, aphasia, agnosia, apraxia, and behavioral abnormalities such as apathy, restlessness, and sleep disorders occur. The disease was first described in 1907 by Alois Alzheimer.

Pons

pons

Area in the brain stem between the medulla oblongata and the mesencephalon. It acts as a switching station for many nerve pathways between the brain and spinal cord and contains numerous nuclei, including cranial nerves and those involved in controlling motor function in cooperation with the cerebellum.

Tegmentum

Tegmentum (from the Latin "tegere," meaning "to cover"). This is the ventral part of the midbrain located beneath the aqueduct. It contains nuclei such as the substantia nigra, the reticular formation, the cranial nerve nuclei, and the red nucleus.

Midbrain

mecencephalon

The midbrain is the uppermost section of the brain stem. Its regions are located around the aqueduct, a canal filled with cerebrospinal fluid. Prominent structures include the tectum, tegmentum, and substantia nigra.

Attention

Attention

Attention serves as a tool for consciously perceiving internal and external stimuli. We achieve this by focusing our mental resources on a limited number of stimuli or pieces of information. While some stimuli automatically attract our attention, we can select others in a controlled manner. The brain also unconsciously processes stimuli that are not currently the focus of our attention.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Plasticity

Neuroplasticity

The term neuroplasticity describes the ability of synapses, nerve cells, and entire areas of the brain to change structurally and functionally depending on the degree to which they are used. Synaptic plasticity refers to the adaptation of the signal transmission strength of synapses to the frequency and intensity of incoming stimuli, for example in the form of long-term potentiation or depression. In addition, the size, interconnection, and activity patterns of different areas of the brain also change depending on their use. This phenomenon is referred to as cortical plasticity when it specifically affects the cortex.

Recommended articles

Serotonin, the mood messenger

Serotonin is found in many foods but cannot enter the brain via the bloodstream. Instead, it is produced locally from the amino acid tryptophan. However, the amount of serotonin in the brain can be influenced by tryptophan levels – and these, in turn, can be influenced by diet. A diet rich in carbohydrates leads to high tryptophan availability, while conversely, studies have shown that carbohydrate withdrawal causes Sleep disorders and depression, which has been attributed to the resulting serotonin deficiency. Many antidepressants and anti-anxiety medications specifically increase the amount of serotonin available in the brain, for example by slowing down presynaptic reuptake. These active ingredients are known as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

Nevertheless, mood cannot simply be improved by increasing serotonin levels. This is also demonstrated by treatment experience with SSRIs: although the active ingredients reach the brain quickly, they only take effect after several weeks of use, and only in cases of severe Depression do they achieve clearly demonstrable success.

Serotonin

A neurotransmitter that acts as a messenger in the transmission of information between neurons at their synapses. It is primarily produced in the raphe nuclei of the brain stem and plays a key role in sleep and alertness, as well as emotional well-being.

Neurotransmitter

A neurotransmitter is a chemical messenger, an intermediary substance. It is released by the sender neuron at the sites of cell-cell communication and has an excitatory or inhibitory effect on the receiver neuron.

Raphe nuclei

The raphe nuclei are located in the reticular system and are distributed throughout the brain stem. They belong to the ascending reticular activating system (ARAS) and are the site of serotonin production.

Brain stem

truncus cerebri

The "trunk" of the brain, to which all other brain structures are "attached," so to speak. From bottom to top, it comprises the medulla oblongata, the pons, and the mesencephalon. It transitions into the spinal cord below. It is a center for vital functions such as breathing and heartbeat and contains ascending and descending pathways between the cerebrum, cerebellum, and spinal cord.

Sleep disorders

A collective term for various phenomena characterized by the fact that those affected do not get restful sleep. Both psychological and organic causes can contribute to this. Symptoms range from problems falling asleep and staying asleep to undesirable behaviors during sleep such as sleepwalking, restless legs when falling asleep, sleep apnea, etc. According to estimates, up to 30 percent of all adults in Western countries suffer from some form of sleep disorder. Finding the causes is often complicated, and analysis in a sleep laboratory is the best method of investigation.

Depression

A mental illness whose main symptoms are sadness and a loss of joy, motivation, and interest. Current classification systems distinguish between different types of depression.

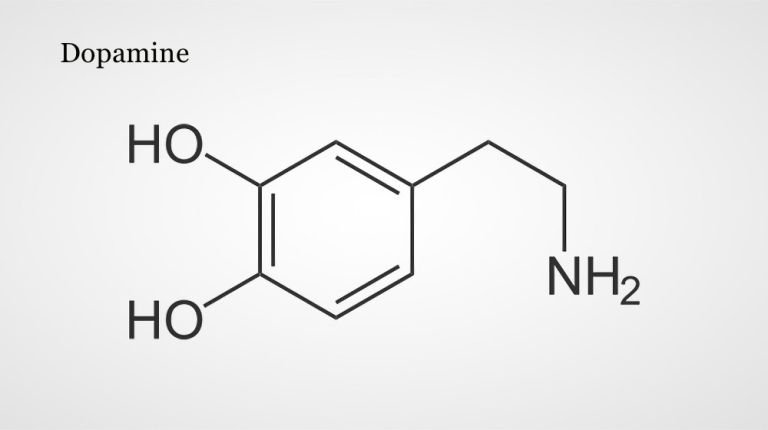

Behavioral regulator dopamine

Dopamine, like norepinephrine and epinephrine – other neurotransmitters that are particularly important in the peripheral Autonomic nervous system (think of the famous “adrenaline rush”) – is produced from the amino acid tyrosine. Before animal experiments rather accidentally revealed its independent significance for the central nervous system, Dopamine was long considered only a chemical precursor of norepinephrine.

Dopamine-containing cells are found in many places in the central nervous system, but two dopaminergic Neuron groups are of particular importance. One is located in the Substantia nigra in the Midbrain and sends its axons to the Striatum. This pathway is important for controlling voluntary movements: if the dopaminergic cells in the substantia nigra degenerate, this triggers fatal motor disorders – Parkinson's disease.

The second dopaminergic system also originates in the midbrain, in the Ventral tegmental area From there, the axons extend to certain parts of the Cerebrum and the Limbic system This pathway is therefore also known as the mesocorticolimbic system and is believed to play an important role in Motivation: it is considered a reward system that reinforces behaviors that are beneficial to survival in both animals and humans. Increasing the amount of dopamine available through appropriate active substances has a stimulating effect – but often also leads to addiction. A well-known example is cocaine: it inhibits the reuptake of dopamine, promoting alertness, increased self-esteem, and euphoria; at the same time, this stimulation of the reward system is addictive.

Other symptoms and mental illnesses are also associated with disorders of the dopamine system. Schizophrenia, for example, is linked to an overactive dopamine system, while a lack of dopamine in the frontal Cortex is thought to contribute to Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Autonomic nervous system

The part of the nervous system that primarily controls unconscious vital functions such as breathing, heartbeat, and blood pressure. The autonomic nervous system is divided into the sympathetic nervous system, which is active in performance and stress situations, and the parasympathetic nervous system, which is active during rest and recovery phases. In some cases, the enteric nervous system, which is responsible for gastrointestinal functions, is also considered part of the autonomic nervous system.

Dopamine

Dopamine is an important neurotransmitter in the central nervous system that belongs to the catecholamine group. It plays a role in motor function, motivation, emotion, and cognitive processes. Disruptions in the function of this transmitter play a role in many brain disorders, such as schizophrenia, depression, Parkinson's disease, and substance dependence.

Neuron

A neuron is a specialized cell in the nervous system that is responsible for processing and transmitting information. It receives signals via its dendrites and transmits them via its axon. Transmission occurs electrically within the neuron and, between neurons, usually chemically via synapses.

Substantia nigra

A nucleus complex in the ventral mesencephalon that plays a central role in initiating and modulating movement. It appears dark due to neuromelanin. Its dopaminergic neurons project via the nigrostriatal pathways to the putamen and caudate nucleus. Failure of these neurons leads to the typical symptoms of Parkinson's disease.

Midbrain

mecencephalon

The midbrain is the uppermost section of the brain stem. Its regions are located around the aqueduct, a canal filled with cerebrospinal fluid. Prominent structures include the tectum, tegmentum, and substantia nigra.

Striatum

Corpus striatum

The striatum is a central structure of the basal ganglia. It consists of the caudate nucleus and putamen; the nucleus accumbens is also functionally part of it as its ventral portion. As the most important input structure of the basal ganglia, the striatum plays an essential role in controlling movement sequences as well as in cognition, motivational processes, and the reward system.

ventral

A positional term – ventral means "towards the abdomen." In relation to the nervous system, it refers to a direction perpendicular to the neural axis, i.e., downwards or forwards.

In animals (that do not walk upright), the term is simpler, as it always means toward the abdomen. Due to the upright posture of humans, the brain bends in relation to the spinal cord, making ventral mean "forward."

Ventral tegmental area

Ventral tegmental area/Area tegmentalis ventralis7ventral tegmental area

Located in the midbrain, the uppermost section of the brain stem, is the ventral tegmental area (VTA) – a central component of the reward system. The area itself is not particularly large, but its influence is immense: the neurons of the VTA send their axons to the nucleus accumbens and widely into the prefrontal cortex (PFC), where they release the neuromodulator dopamine. In this way, they enhance learning processes, but can also contribute to the development of addictions.

Cerebrum

telencephalon

The cerebrum comprises the cerebral cortex (gray matter), the nerve fibers (white matter), and the basal ganglia. It is the largest part of the brain. The cortex can be divided into four cortical areas: the temporal lobe, frontal lobe, occipital lobe, and parietal lobe.

Its functions include the coordination of perception, motivation, learning, and thinking.

Limbic system

The limbic system is a functional unit in the brain. It consists of interconnected structures, primarily in the cerebrum and diencephalon. The structures assigned to the system vary depending on the source, but the most important components are the hippocampus, amygdala, cingulate gyrus, septum, and mammillary bodies. The limbic system is involved in autonomic and visceral processes as well as in mechanisms of emotion, memory, and learning. Some authors mistakenly reduce the limbic system to the emotional world by referring to it as the "emotional brain."

Motivation

A motive is a reason. When this motive takes effect, the living being feels motivation – it strives to satisfy its need. For example, for food, protection, or reproduction. Motivation can be intrinsic (from within, e.g., curiosity) or extrinsic (from outside, e.g., reward).

frontal

An anatomical position designation – frontal means "towards the forehead," i.e., at the front.

Cortex

cortex cerebri

Cortex refers to a collection of neurons, typically in the form of a thin surface. However, it usually refers to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of the cerebrum. It is 2.5 mm to 5 mm thick and rich in nerve cells. The cerebral cortex is heavily folded, comparable to a handkerchief in a cup. This creates numerous convolutions (gyri), fissures (fissurae), and sulci. Unfolded, the surface area of the cortex is approximately 1,800cm².

Attention

Attention

Attention serves as a tool for consciously perceiving internal and external stimuli. We achieve this by focusing our mental resources on a limited number of stimuli or pieces of information. While some stimuli automatically attract our attention, we can select others in a controlled manner. The brain also unconsciously processes stimuli that are not currently the focus of our attention.

First published: February 2, 2018

Last updated on August 5, 2025