MS under the microscope

Multiple sclerosis – scarring in the brain – is caused by damage to axons: it forms the basis of a wide range of neurological symptoms.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Hans-Peter Hartung, Dr. Melanie Schütte

Published: 15.08.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

Scattered areas of inflammation in the tissue of the brain and spinal cord are typical of multiple sclerosis.

The optic nerves, spinal cord, brain stem, and the medulla around the ventricles are particularly affected.

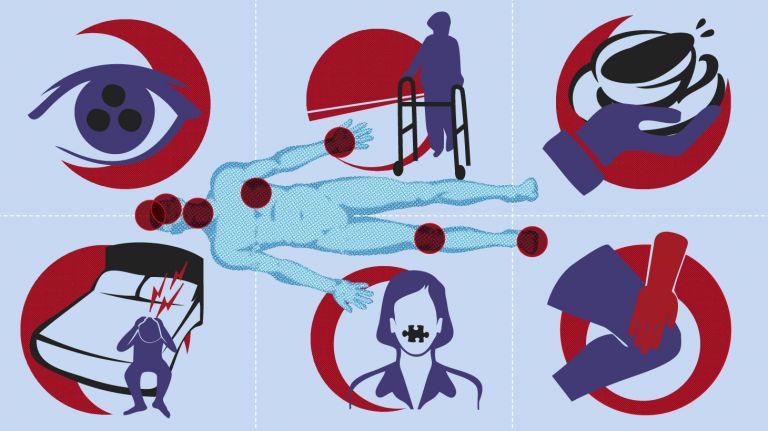

The symptoms are a consequence of damaged nerve sheaths and, as the disease progresses, the nerves themselves, depending on the location of the damage.

Effective medications are available for the relapsing-remitting course of the disease.

Depending on the location – brain or spinal cord – and the extent of the damage, the symptoms vary greatly. Typical optic neuritis is often the first episode of MS, occurring in 40 percent of those affected.

Damaged nerve fibers in the brain stem can cause trigeminal neuralgia, paralysis of the eye muscles, and double vision. If the nerves that supply the facial muscles are inflamed, facial paralysis can occur. Dizziness and nausea arise when nerve pathways that connect to the vestibular system are damaged. Inflammation in the brain stem can also lead to slurred speech.

If nerve fibers in the cerebellum or its connecting pathways are affected, this leads to disturbances in movement or standing, jerky speech, or excessive movements. If fibers in the spinal cord are damaged, this triggers sensory disturbances (tingling, numbness) and motor disturbances.

The muscles can either slacken or cramp up. Other symptoms include bladder and rectal disorders, urinary dribbling and urinary urgency, or loss of bladder or bowel control. Spasticity, incontinence, or sensory disturbances also cause sexual problems in many MS patients, which can manifest as loss of libido, inability to orgasm, or loss of potency.

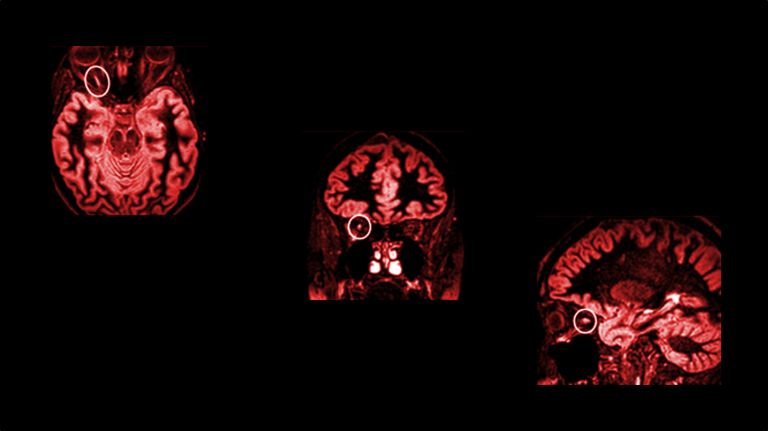

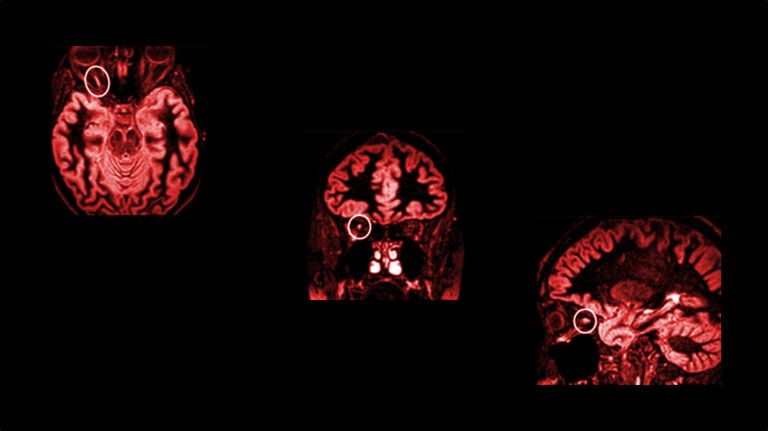

Until a few years ago, the relapsing-remitting nature of MS made early diagnosis difficult. However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) now allows the inflammatory lesions typical of MS to be detected in more than 70 percent of patients at a stage when only initial, non-specific symptoms are present.

The McDonald criteria for diagnosing MS are currently being updated to enable earlier and more accurate diagnosis. The first presentation took place in 2024, and the final criteria have yet to be published. For example, the detection of characteristic patterns (oligoclonal bands) and biomarkers in the spinal fluid, and the expanded inclusion of inflammatory lesions of different ages and with a specific distribution, can help doctors make a faster diagnosis. The penultimate update in 2017 already succeeded in reducing the time to diagnosis from an average of 7.4 months (according to the 2010 criteria) to around 2.3 months.

Imaging is sometimes used to detect damage to the brain in completely asymptomatic patients, indicating an inflammatory disease of the CNS. This so-called “radiologically isolated syndrome” indicates that a first clinical relapse is to be expected in the near future. In some of these patients, the detection of specific MRI features or biomarkers according to the proposed McDonald criteria 2024 would allow a reliable diagnosis and thus also an earlier start of treatment.

Multiple sclerosis loosely translates as “multiple scarring.” This name was chosen around 100 years ago because MS causes inflammation of nerves in various parts of the brain and spinal cord, and scarring occurs when the inflammation subsides. In fact, however, “encephalitis disseminata” better describes the disease process: in encephalitis, the nerve tissue of the brain and/or spinal cord becomes inflamed, and disseminata refers to the scattered occurrence of the inflammatory foci.

The French pathologist and neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-1893) was the first to describe the symptoms: His “Charcot's triad” – nystagmus (eye tremors), intention tremor, and choppy speech – was long considered characteristic of MS. We now know that the triad only occurs when MS affects the cerebellum, which is not that common, and that it also occurs in other diseases.

Augustus Frederick d'Este (1794-1848), a grandson of British King George III, was the first to record the progression of the then unknown disease in his diary. The first symptoms to appear in d'Este at the age of 28 were visual disturbances, followed by pain, partial paralysis, and sensory disturbances.

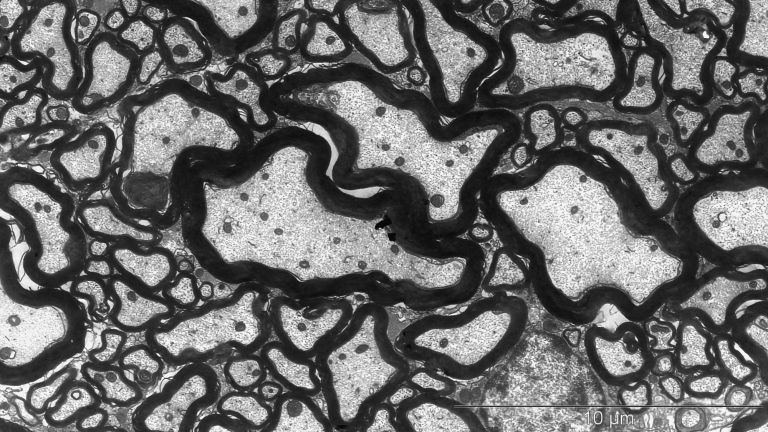

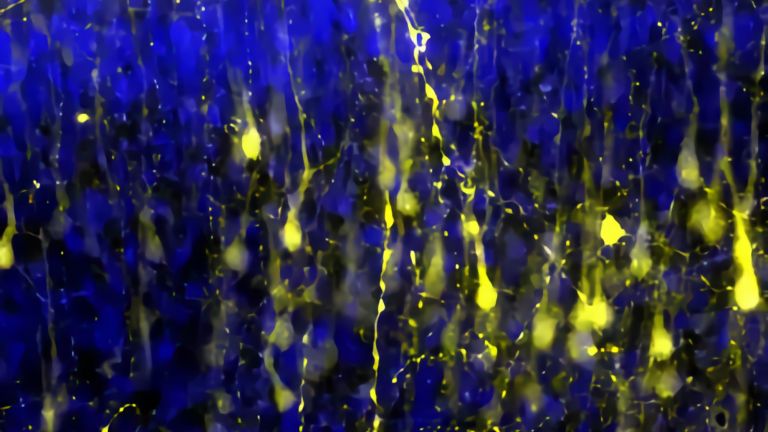

Damaged axons as the basis of the symptoms

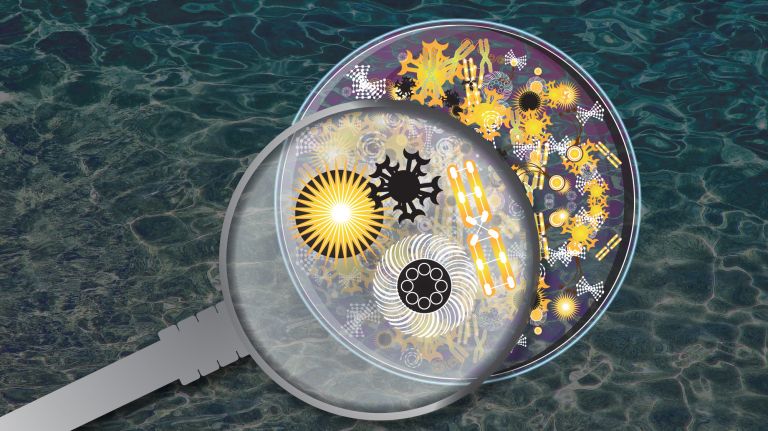

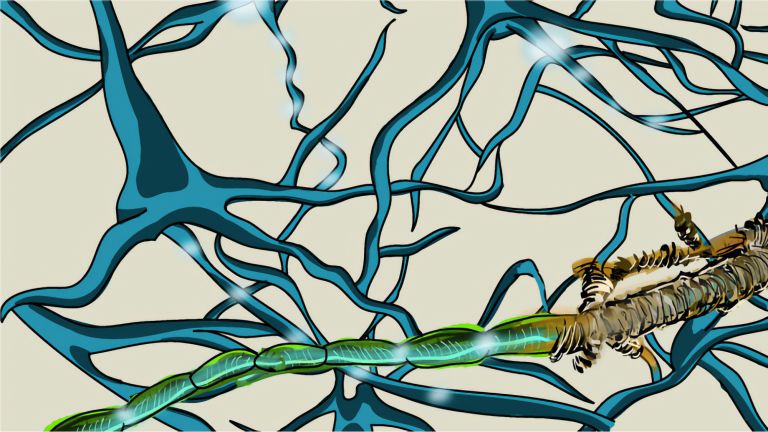

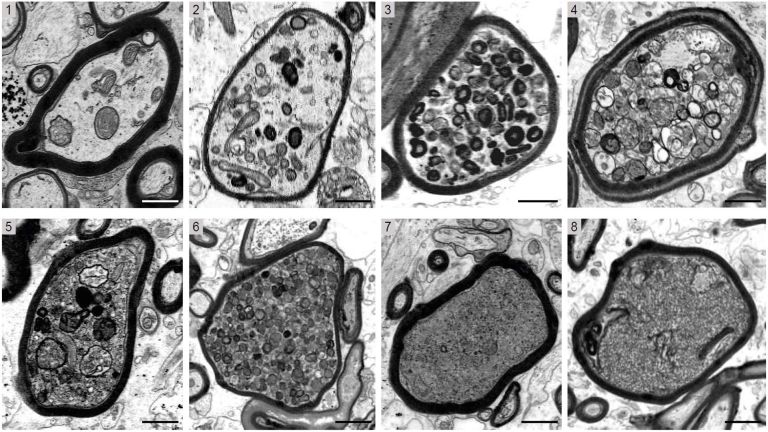

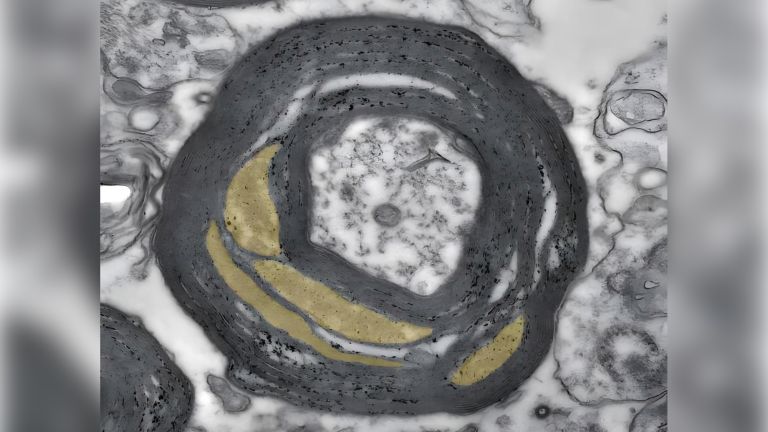

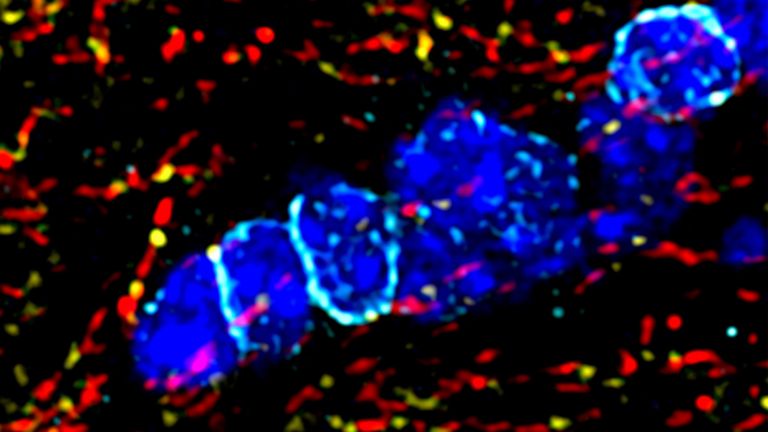

In MS, the immune system attacks the insulating layer of the axons. Special glial cells, called oligodendrocytes, form the myelin sheaths of the axons in the gray and white matter of the central nervous system (CNS), comparable to the insulating layer of an electrical cable. Gaps between the myelin sheaths, known as Ranvier's nodes, enable high conduction speeds in the transmission of nerve impulses, which can reach up to 432 km/h in humans. In addition, according to recent findings, oligodendrocytes supply the axons with important nutrients. The immune cells activated by MS cause inflammation in this myelin layer. When the acute inflammation subsides, fibrous scar tissue forms at the site – these scars then also interfere with information transmission. In advanced stages of the disease, the nerves themselves (the axons) can also be damaged.

In principle, inflammation can occur in all areas of the CNS. However, the optic nerves, spinal cord, brain stem, and the medulla around the ventricles are particularly affected. Inflammatory foci also frequently occur in the poles of the ventricles and in the spinal cord. There is a close connection between the location of the damage and the symptoms that occur (see box).

Around 85 percent of MS patients suffer from the relapsing-remitting form of MS. In this form, remyelination occurs in the early stages of the disease: the myelin sheaths are rebuilt, the neurological deficits disappear completely, and the transmission of impulses is compensated for. However, the myelin sheaths remain thinner. As the disease progresses and depending on its activity, reconstruction is only partial, leading to permanent disabilities.

Recommended articles

Oligodendrocytes as fuel stations for the data highways

Although oligodendrocytes initially form new myelin sheaths, they become increasingly less able to do so as the disease progresses. In addition to the myelin sheaths, the oligodendrocytes themselves can also be attacked and destroyed by the immune cells. Oligodendrocytes play a key role in the formation and maintenance of an intact myelin sheath. But insulating axons is not their only task: supplying axons is an even older evolutionary function. Klaus-Armin Nave, director of the Department of Neurogenetics at the Max Planck Institute for Multidisciplinary Sciences in Göttingen, calls oligodendrocytes the “gas stations of the data highways” of the nervous system because of their supply function for the axon.

The ability to form myelin decreases significantly with age. As a result, the accumulation of disabilities is strongly age-dependent. Damaged axons are no longer electrically insulated and supplied with nutrients, resulting in the death not only of the axons themselves, but also of their nerve cells. This results in diffuse lesions of the white matter and a decline in brain mass and volume.

Studies pointing to specific age-related changes in histones provide an explanation. These are proteins that play an important role in packaging genetic material in the cell nucleus. Chemical signals (acetyl groups) attached to the histones loosen the “packaging” at certain points. This appears to prevent the precursor cells of oligodendrocytes from developing into mature, myelin-forming oligodendrocytes.

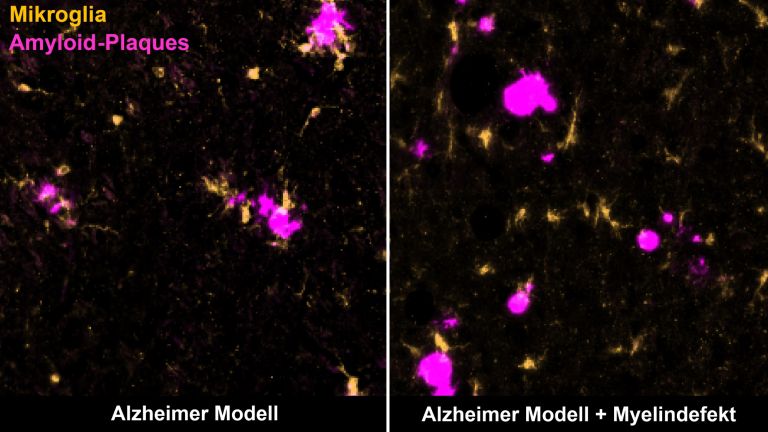

Researchers often use the model of experimental autoimmune encephalitis (EAE) to study the disease process and test new therapeutic approaches. In this model, laboratory animals are vaccinated against the body's own myelin components. As a result, the immune system attacks myelin and oligodendrocytes, destroying the myelin sheaths. Isolated autoreactive T lymphocytes from animals with this disease can also cause the symptoms of the disease when transferred to healthy animals.

According to Nave, the focus on the EAE model is too one-sided. It is similar to MS, because there are also cells that target the body's own myelin components. However, the question is which came first, the chicken or the egg. Other models are just as important for understanding the disease. These include models in which primary neurodegenerative changes in the axon or glial cell can lead to secondary inflammation. This also activates T cells, which in turn can cause damage.

Parallel to research into the fundamental mechanisms of the disease, great progress has been made in the treatment of MS in recent decades. Although it is still the most common cause of neurological disability in younger adults, its progression can be slowed in most patients and the onset of disability delayed, sometimes even prevented altogether. Average life expectancy has also increased significantly and is now approaching that of the general population.

Medical options for relapsing and progressive MS

Effective therapies are available for relapsing MS. Injectable beta interferons (interferon beta-1a and interferon beta-1b) and glatiramer acetate have long been used as basic therapies. In recent years, dimethyl fumarate, diroximel fumarate, and teriflunomide have been added to the list. They reduce the number of inflammatory lesions in the brain and reduce the number of relapses by 30 to 50 percent compared to placebo.

If the effect is insufficient, or if the MS takes an aggressive course from the outset, half a dozen active substances are now available: the S1P modulators fingolimod, ponesimod, and ozanimod; natalizumab, ocrelizumab, ofatumumab/ublituximab, cladribine, and, as a reserve medication if the other therapy options fail, alemtuzumab. These achieve a 50–80% reduction in relapses, but some carry higher risks.

In the approximately 15 percent of all patients with primary progressive MS (PPMS), the symptoms increase from the onset of the disease – either slowly and continuously or irregularly, with phases of temporary stabilization or even temporary slight improvement. In secondary progressive MS, the disease initially progresses in relapses and then becomes continuously progressive. A relapsing course can transition to a secondary progressive course at any time; sometimes soon after the first onset of the disease, sometimes only after several relapses. In both forms, treatment is significantly more difficult than in relapsing MS.

The only therapy approved to date for PPMS is the antibody ocrelizumab, which has proven particularly effective in younger patients with inflammatory activity. Ocrelizumab is also approved for active secondary progressive disease, as is siponimod.

Despite many unresolved problems, most doctors and scientists today see the glass as half full. Just a few decades ago, multiple sclerosis was considered largely untreatable – today, there are more than a dozen approved therapies available that can positively influence the course of the disease. It is particularly encouraging that progress is also being made in progressive MS, for example through antibody therapies, remyelination approaches, and neuroprotective strategies.

“We are no longer at the beginning – we are in the middle of a phase in which we are getting better and better at controlling multiple sclerosis and may even be able to cure it one day,” says Prof. Dr. Frauke Zipp, neurologist at the University Medical Center Mainz and member of the German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina. “What seemed impossible 15 years ago is now a reality: patients with MS can lead an almost normal life.”

First published on November 1, 2017

Last updated on August 15, 2025