Immune System out of Control

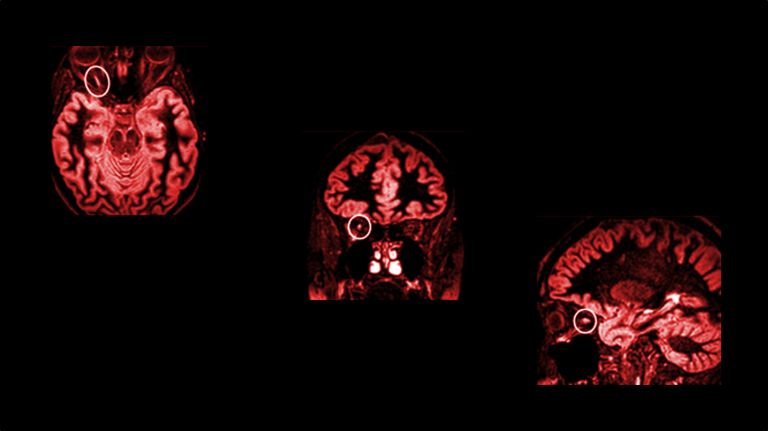

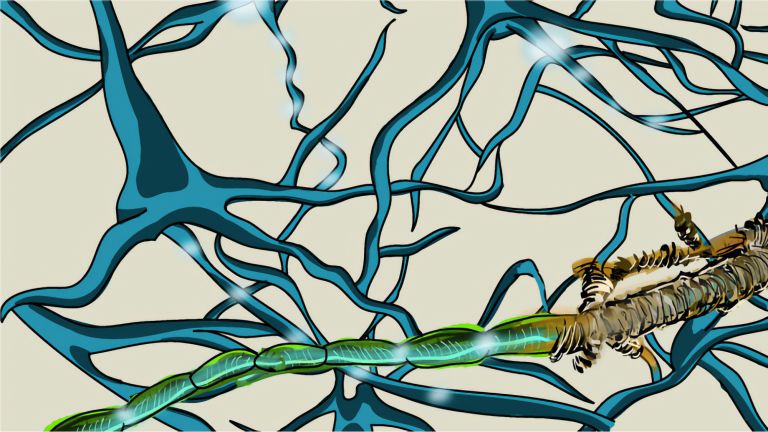

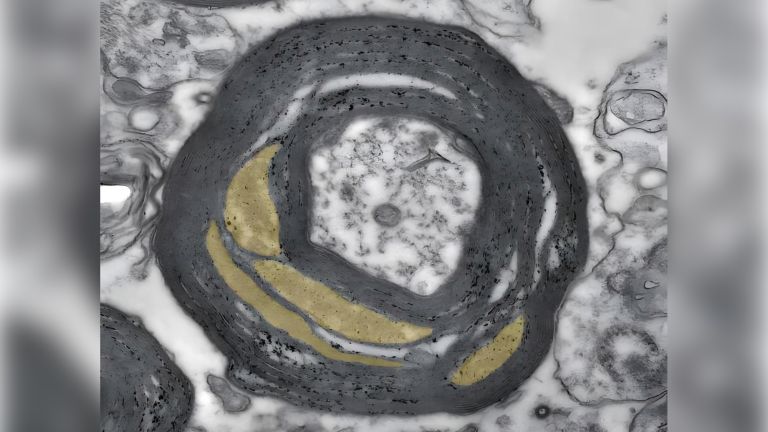

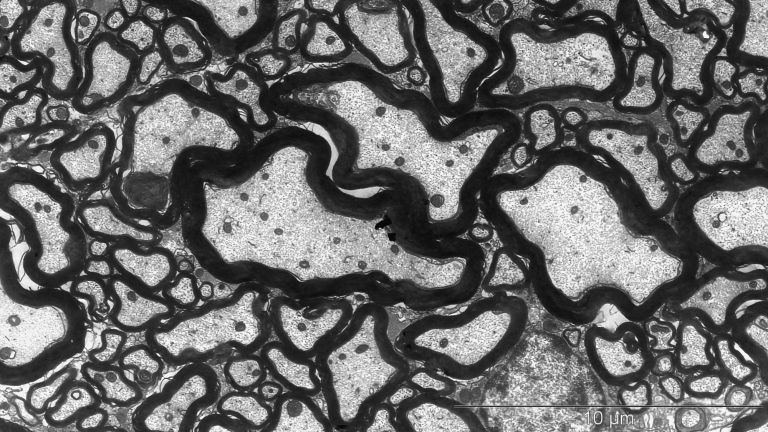

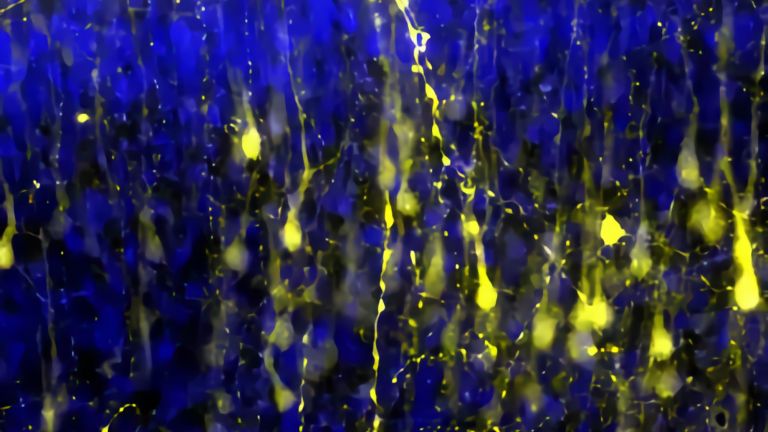

In multiple sclerosis, the body's own structures are misinterpreted as foreign invaders and attacked. Inflammation then destroys not only the electrical insulation of nerve fibers, but also the neurons themselves.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Ricarda Diem, Prof. Dr. Bernhard Hemmer

Published: 08.12.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

- Multiple sclerosis (MS) probably starts in the peripheral immune system: it confuses proteins in the central nervous system (CNS) with hostile viruses and initiates defensive measures.

- As part of the initial response, T and B immune system cells travel from the periphery across the blood-brain barrier into the brain. There, they release messenger substances that open the barrier.

- As a rearguard, further inflammatory cells arrive, attacking the myelin sheaths and thus causing the relapses that characterize the early stages of the disease.

- Contrary to what was long believed, however, the inflammatory reactions continue in later phases, during which the disease can progress. However, they take place behind a blood-brain barrier that has closed again and is disconnected from the peripheral immune system. It remains unclear whether the immune system promotes the destruction of nerve cells in this phase, or whether it is a reaction to the destruction of nerve cells.

- In the future, it will be important to treat MS in a more targeted manner and to block only the harmful immune cells. In addition, new therapeutic approaches are needed that specifically target the chronic progressive phase.

Despite all the efforts of researchers, the actual cause of multiple sclerosis remains unknown. “There is a polygenetic predisposition to MS,” says Wolfgang Brück, Director of Research and Teaching at the Institute of Neuropathology at Göttingen University Medical Center. Today, more than 230 risk genes are known to contribute to the onset of MS. “And what is striking is that all of these risk genes are related to the immune system.” In addition, there are environmental factors such as viral infections (especially the Epstein-Barr virus) that, while not directly causing MS, may cause changes in the immune system, ultimately leading immune cells to attack the brain and spinal cord.

“We know that immune cells migrate from the periphery to the brain,” says Manuel Friese, Director of the Institute for Neuroimmunology and Multiple Sclerosis at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf. "However, it is not yet fully understood whether MS actually begins in the immune system in the periphery or in the CNS. Some researchers see this activity of the immune system merely as a reaction to processes that originate in the CNS. However, what these processes might be is currently completely unclear.

It's like a game of dominoes: as soon as the first stone falls, multiple sclerosis (MS) triggers a fatal chain reaction that reaches the brain and causes devastating damage there. In this disease, the immune system goes haywire and attacks the body's own tissue. In at least some of those affected, this leads to limitations in everyday life in the medium term. Although the mechanisms of MS are only partially understood, early therapeutic intervention is essential to influence its course.

One of the first dominoes to fall, triggering the rest, probably does not fall in the brain. In the early stages, when the disease occurs in episodes separated by months of recovery, the peripheral immune system is likely to be the trigger for the chain reaction. In order for the immune system to do its job properly, it must first distinguish between “friend” and “foe,” between the body's own cells and foreign invaders. But in MS, this process goes wrong.

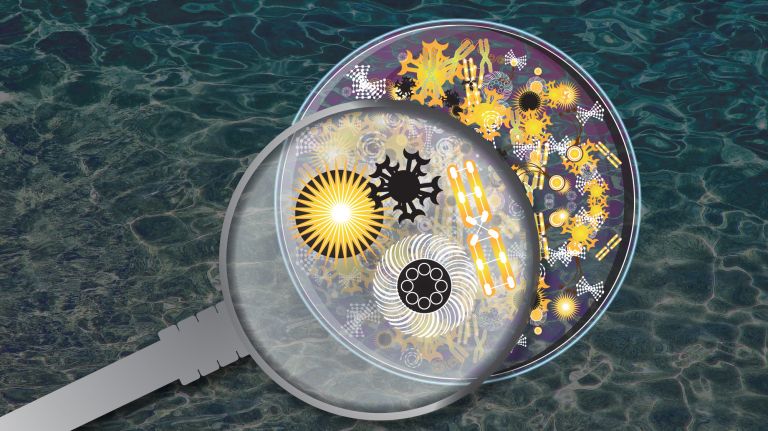

It probably happens like this: The immune system is activated by an infection in the lymph nodes or spleen. Infection with the Epstein-Barr virus probably plays a central role here. As part of the fight against the virus, immune cells are activated that cross-react with proteins in the brain and spinal cord. This causes the immune system to mistakenly focus on the CNS.

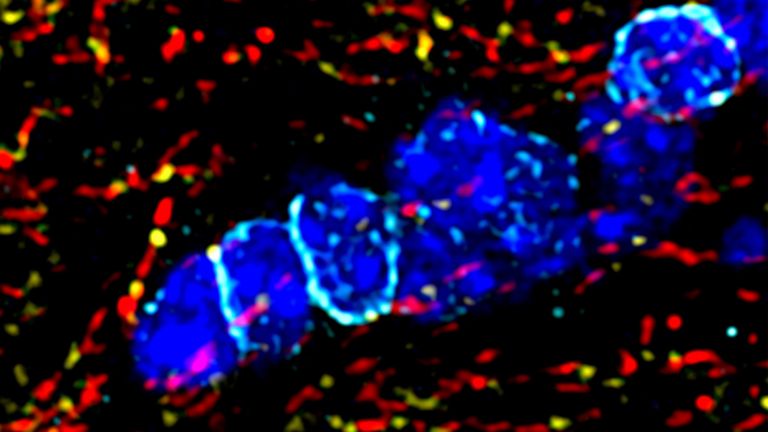

The activated T- and B-cells (lymphocytes) make their way to the brain via the bloodstream. There, they must first cross the blood-brain barrier. This powerful barrier separates the bloodstream from the brain and ensures that no foreign substances, pathogens, or toxic metabolic products enter the brain. “The T- and B-cells cross the blood-brain barrier via so-called integrin molecules, which are located on their surface,” says Manuel Friese. “These molecules enable the lymphocytes to ‘dock’ at binding sites on the vessel wall and migrate into the tissue of the central nervous system.” says the director of the Institute of Neuroimmunology and Multiple Sclerosis at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf. Once in the brain, the lymphocytes release messenger substances that open the previously intact barrier.

Inflammation and nerve death

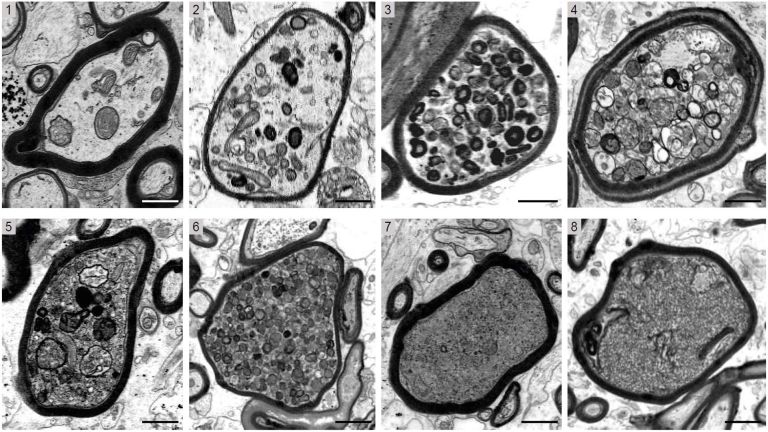

Now that the path to the brain is clear, the chain reaction takes its course. The next dominoes fall as more inflammatory cells invade the brain and attack glial cells and nerve cells. The resulting inflammation causes functional disorders in the affected nerve strands, leading to corresponding neurological impairments. In MS, these range from sensory disturbances, paralysis, and visual disturbances to neuropsychological deficits. “With each wave of inflammatory cells in the brain, damage occurs and possibly new relapses in patients,” says Wolfgang Brück, Director of Research and Teaching at the Institute of Neuropathology at the University Medical Center Göttingen. It was previously thought that such inflammatory processes only occurred in the early, relapsing phases of MS. In later phases, as the disease progresses, nerve cells would degenerate. “Today, however, we know that nerve cells and their extensions degenerate even in the early phases and that inflammatory reactions also play an important role in the progressive phases.”

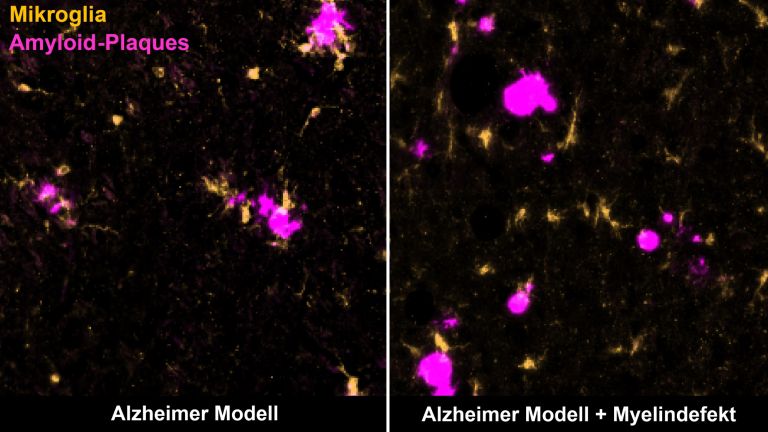

However, the circumstances in the late phases of the disease are different. The previously open blood-brain barrier has closed again. From now on, the inflammatory reactions take place directly in the brain, behind a closed curtain, so to speak, disconnected from the peripheral immune system. After all, the brain also has its own immune defense. Its ranks include microglia cells, which constantly comb through the tissue with hair-thin arms. In an emergency, they quickly migrate to the site of the disaster and eat up pathogens. The role of microglia is still unclear. On the one hand, they could maintain the inflammation, which then leads to nerve damage. On the other hand, microglia also become active when nerve damage occurs through other mechanisms. In this case, microglia activation is not the cause, but the consequence of nerve damage.

Therapy so far only one-sided

“This also explains in part why drugs that inhibit the immune system and work quite well in the relapsing-remitting phase of MS have little effect in the progressive form,” says Wolfgang Brück. These drugs target the immune response in the periphery, ensuring that lymphocytes do not enter the central nervous system. “For effective therapy, you actually need drugs that work locally, in the brain.”

Manuel Friese takes a similar view: “Medications can block the passage of T-cells into the central nervous system.” This would stop the inflammatory episodes and reduce damage to the brain. However, it would not reliably prevent the slow progression of the disease and disability that occurs between episodes. Friese has long suspected that it is not the T-cells that drive the disease and disability. They are merely the trigger for inflammation that later occurs autonomously in the brain. In fact, it has long been known that B-cells also play a central role in immunopathogenesis. Not only do they contribute to antibody production, they also influence T-cell activation and cytokine production.

Recommended articles

Good sides, bad sides

However, it is important to remember that the immune response does not only have its bad sides. “It also promotes regeneration in the brain,” says Wolfgang Brück. So it cannot be just a matter of slowing down and blocking the immune system. “That would also suppress the positive aspects of the immune response.” However, we do not yet know exactly which immune cells are good and which are bad. In the future, we will need to identify the subgroups of inflammatory cells that are actually negative and target them therapeutically. “We must protect the beneficial portion of the inflammatory cells,” says Brück, speculating on the future of MS therapy.

Further reading

- Stadelmann C, Franz J, Nessler S. Recent developments in multiple sclerosis neuropathology. Curr Opin Neurol. 2025;38(3):173-179. doi:10.1097/WCO.0000000000001370. Full text.

- German Society of Neurology: Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment in Neurology (German)

Hemmer B., Gehring K. et al. Diagnose und Therapie der Multiplen Sklerose, Neuromyelitis-optica-Spektrum-Erkrankungen und MOG-IgG-assoziierten Erkrankungen, S2k-Leitlinie, 2024, in: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie (Hrsg.), Leitlinien für Diagnostik und Therapie in der Neurologie. (Online), abgerufen am 9.12.2025.

First published on May 1, 2017

Last updated on December 8, 2025