Networks of Movement: Control Strategy, Tactics, Execution

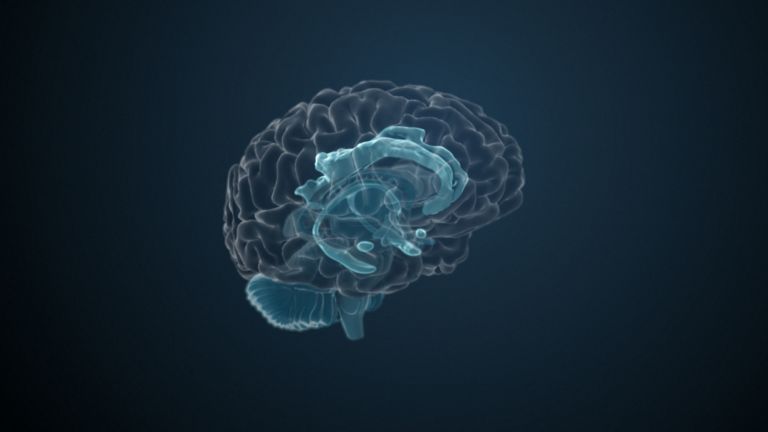

Whether we are throwing a ball, climbing a tree, or singing an aria, every voluntary movement of our body begins in the brain. A network of different brain areas with different specialized functions works together to plan and organize every movement.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Hansjörg Scherberger

Published: 01.12.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

- Human movements are controlled and regulated by a network of different brain areas.

- This involves large parts of the cerebral cortex and brain stem, as well as the cerebellum and spinal cord.

- The brain regions belonging to the motor system have different areas of responsibility and special functions, from determining the movement strategy to the concrete planning of the movement and its execution.

It's early in the morning, the alarm clock is ringing. Still half asleep, you flinch, blink your eyes, grope for the alarm clock, and turn off the alarm. Then you stretch, roll over, throw back the covers, swing your legs over the edge of the bed – and another day begins in which we move without interruption. Even when sitting relatively still in front of the computer, the body is always in action. Your eyes wander across the screen, your facial muscles briefly frown, your fingers rush across the keyboard, and in between, you thoughtfully scratch your ear. In short, motor skills are essential for human existence.

Interplay of action and reaction

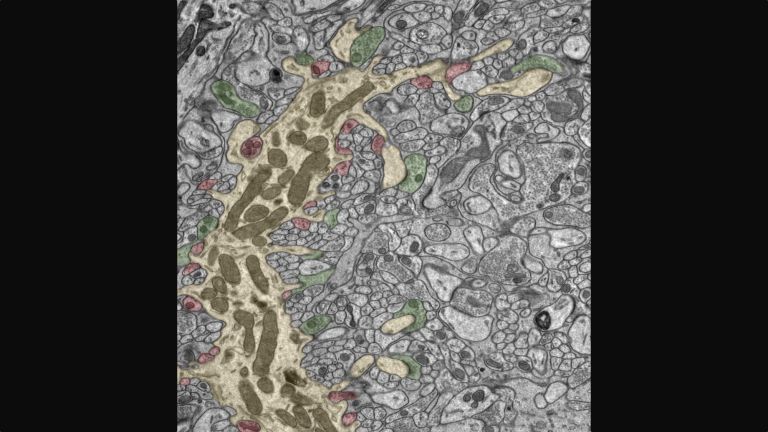

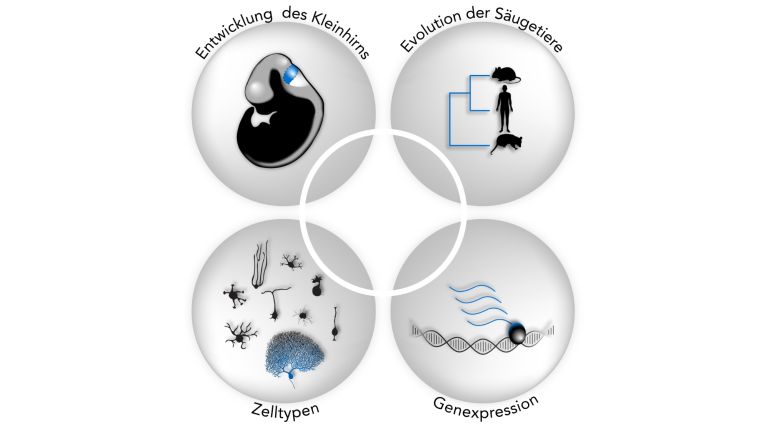

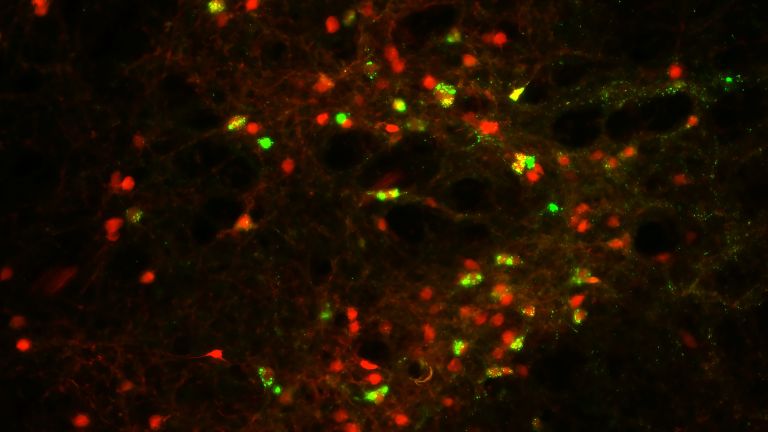

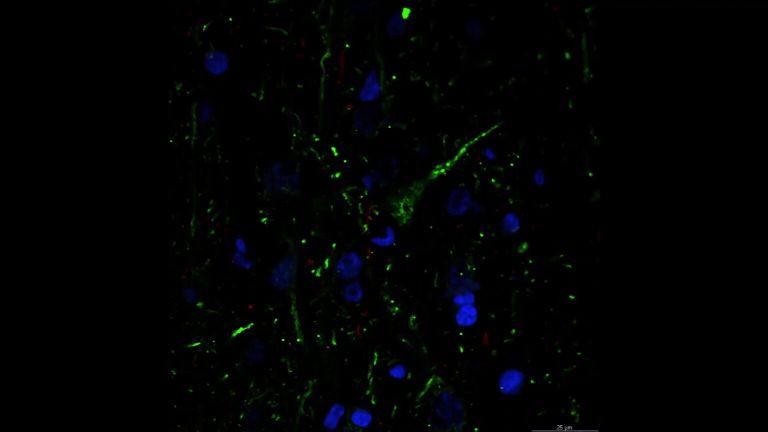

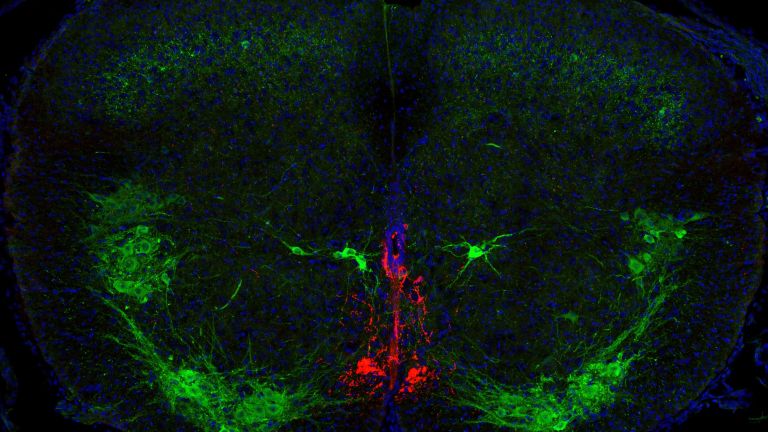

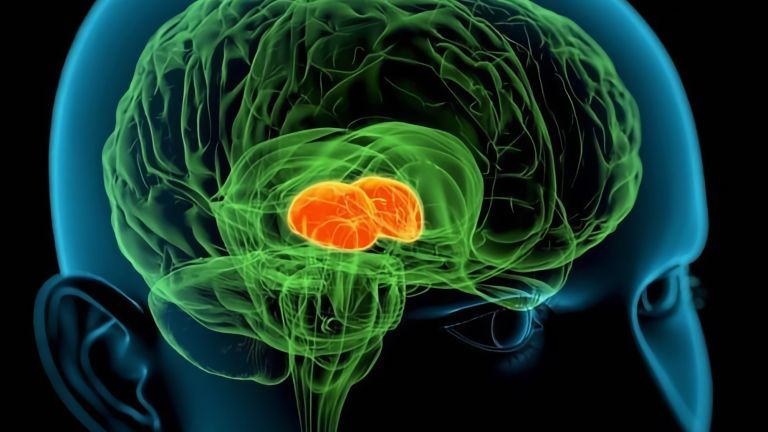

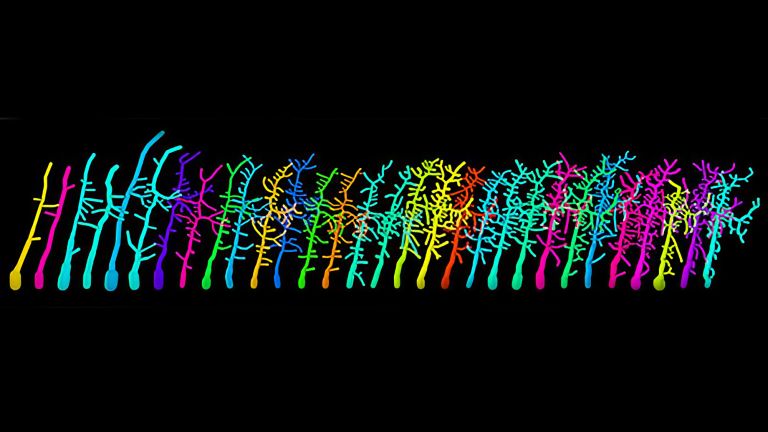

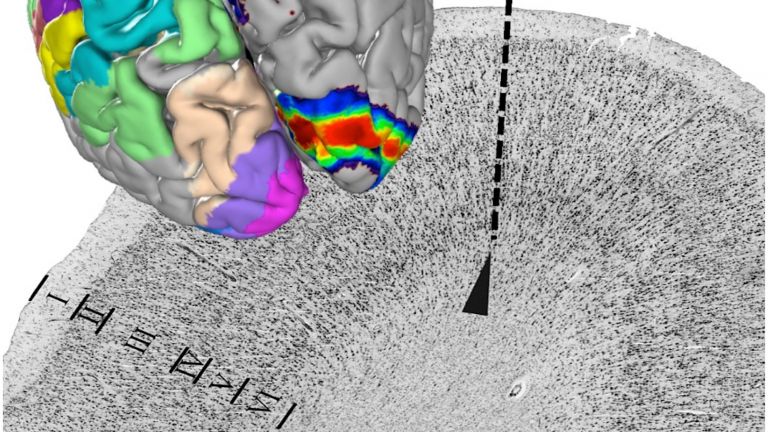

The importance of motor skills is also evident when looking at the central nervous system and the neurobiology behind it. In addition to areas of the brain stem, spinal cord, and cerebellum, large parts of the cerebral cortex, which is considered the seat of higher brain functions, are also largely occupied with planning and controlling movements.

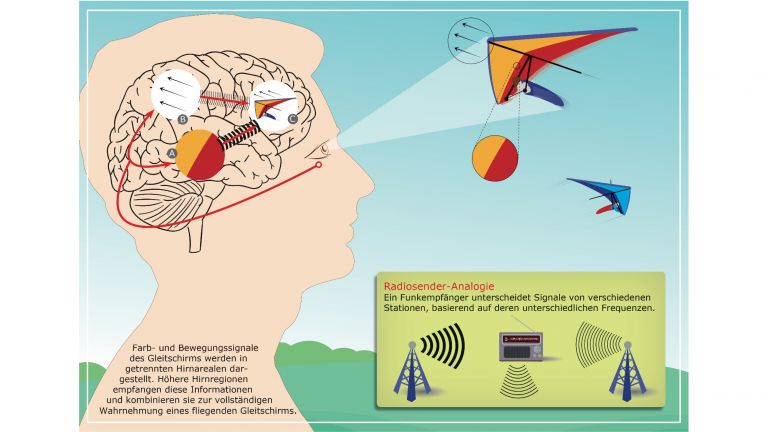

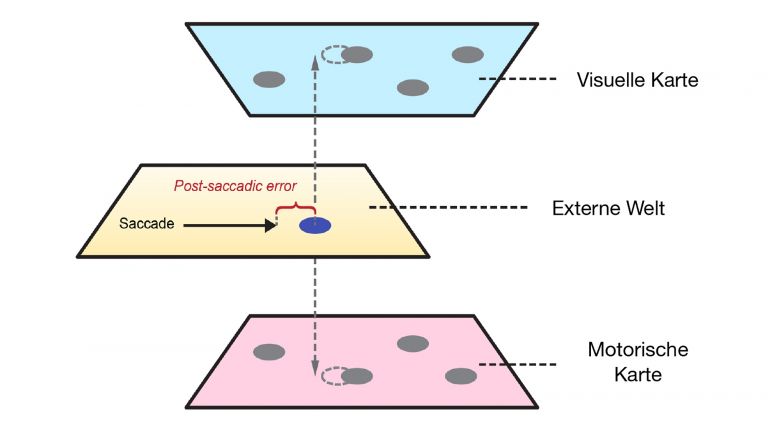

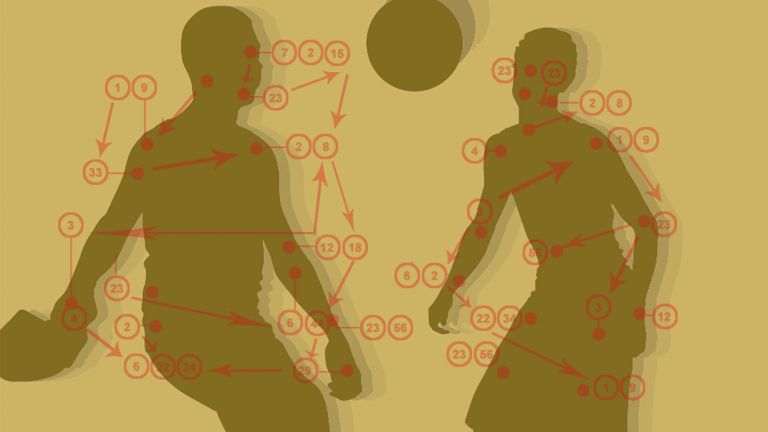

This task is accomplished in several steps by a network of different brain areas with different specialized functions, but which work closely together: First, the goal of a motor action is determined, then a tactic for optimal implementation of the whole is developed. Finally, the movement is executed – and if something does not work as desired, messengers send the bad news back up to the top, where a decision is then made to change the strategy.

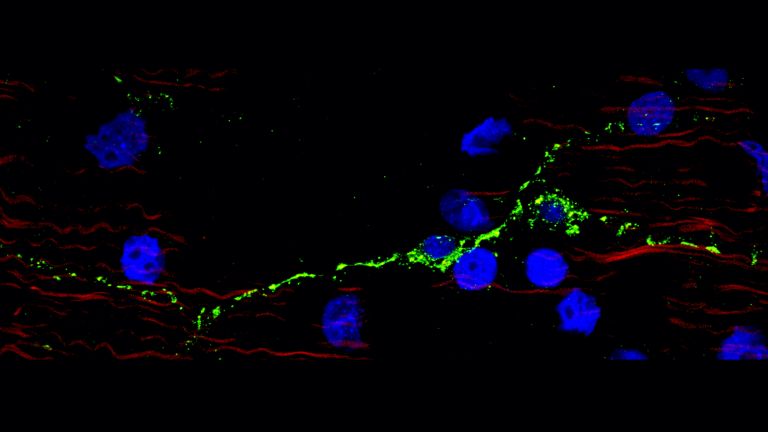

This means that signals and information do not only travel from the motor system in the brain to the muscles, but conversely, messages are also constantly sent back from the body's periphery to the command center in a kind of feedback loop. For example, special cells in the muscles, tendons, and joints, called proprioceptors, provide the brain with feedback on the position of the body in space, and sensory cells report on the force of the respective movement or its success. Only in this way can the brain perceive the effects of a movement and, in case of doubt, initiate an improved second attempt. In other words, sensory information is indispensable for movement control. That is why it would be more accurate to speak not only of the motor system, but also of the sensorimotor system.

However, in order for this feedback to occur in the first place, the brain must first initiate a movement. What exactly happens in what order can be easily understood by looking at the example of a tennis player serving. Their goal is always to hit the ball into their opponent's court in such a way that they cannot return it, or at least cannot return it well. There are several options to choose from: the high-bouncing kick serve played with forward spin, the slice serve played with side spin that almost slips away, or simply the straight and hard serve. In addition, the server can vary the direction – far to the side, directly through the middle at the body. Depending on where his opponent's strengths and weaknesses lie, and depending on what move he himself has in mind – such as a net attack – one variant may be the better choice at one time, and another at another.

Determining a movement strategy

Before the athlete swings for what may be the decisive serve, i.e., before the complex sequence of muscle contractions behind it can be planned and set in motion, they must consider which technique to choose. This requires information about the position of their body and that of their opponent, but also data such as wind speed and direction. In other words, a mental image of the situation.

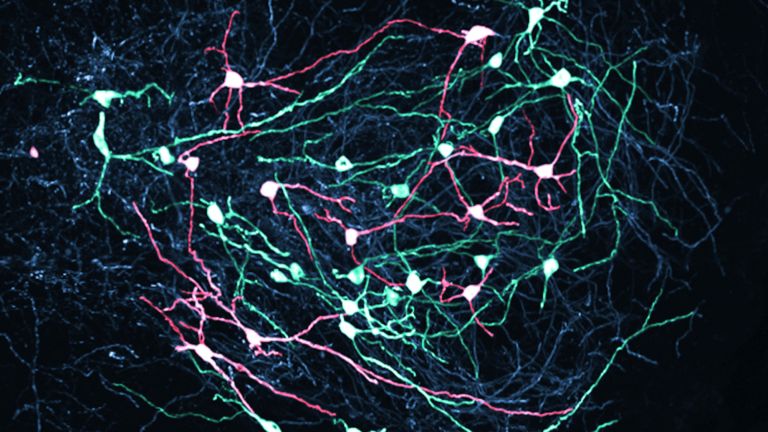

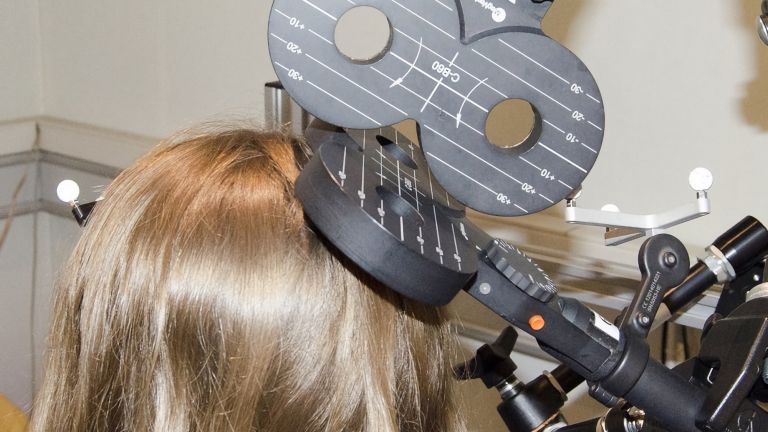

The somatosensory, proprioceptive, and visual information required for this is processed in the posterior parietal cortex at the top of the back of the head. The parietal cortex is closely linked to regions in the anterior frontal lobe, which are central to abstract thinking, decision-making, and assessing the consequences of an action.

Together with the posterior parietal cortex, these prefrontal areas are responsible for determining the goal of a movement and clarifying the strategy that best achieves it. This is where decisions about courses of action are made, including the type of serve. Previous experiences that the tennis player has had in the course of the match play an important role here. For example, that the opponent's backhand is weaker than their forehand. The strategic considerations could then look like this:

Movement goal 1: Force the opponent to make a mistake or a harmless return with the serve in order to win the point and thus the match.

Movement goal 2: Do not make a serve error yourself.

Information A: Opponent has shown weaknesses with their backhand.

Information B: The kick serve is the safest option.

Information C: The opponent is standing relatively far on their forehand side.

Ergo, best strategy: A kick serve to the backhand side, with a safe distance to the sideline to minimize the risk of an out ball.

Recommended articles

Planning and initiation

Both the prefrontal and parietal cortex send axons to the premotor and supplementary motor areas. In these two areas of the cerebral cortex, which belong to the motor cortex, the decision is stored until execution – for example, if the server cannot start immediately because his opponent is wiping his hands on his pants to get a better grip on the racket. Once it is clear that it is now possible to start, information that is conveyed via various other stages, the strategy is implemented. Now a movement plan must be created that specifies which muscles are to be tensed - in what order and with what intensity.

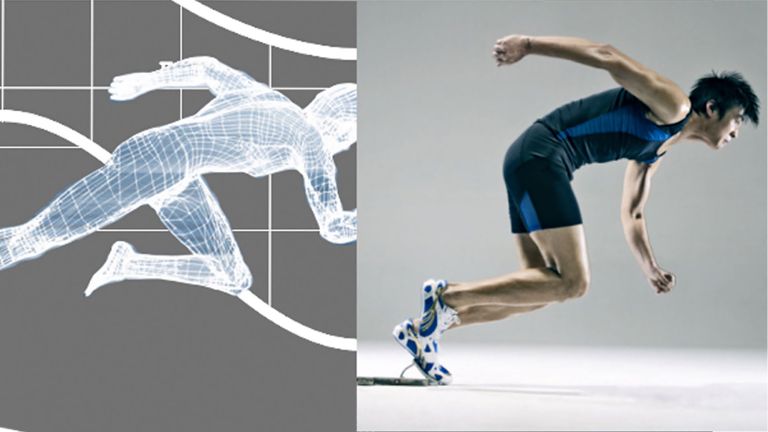

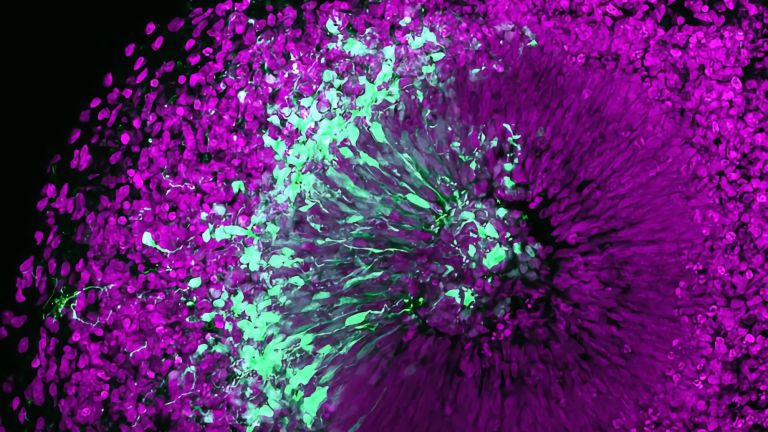

The motor cortex, basal ganglia, and cerebellum are responsible for organizing the spatial and temporal sequence of muscle contractions in such a way that the movement goal is optimally achieved. While the frontal and parietal cortex determine the “what,” these areas of the brain determine the “how” of a motor action. Patients with damage to the cerebellum clearly demonstrate how important it is for the development of our motor skills. Even simple sequences of movements are an impossible task for these individuals because, for example, when reaching for a glass, they cannot lower their arm, open their hand, and then close their fingers in sequence, but instead perform the individual movements in a disorderly manner. The clumsiness of drunk people is also mainly caused by alcohol-induced functional impairment of the cerebellum.

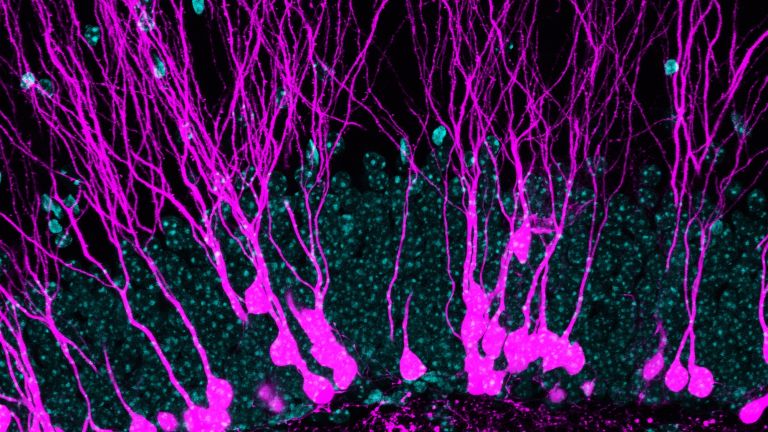

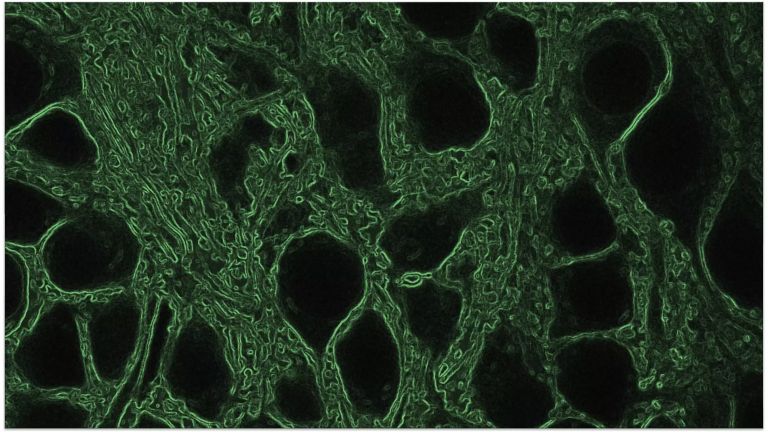

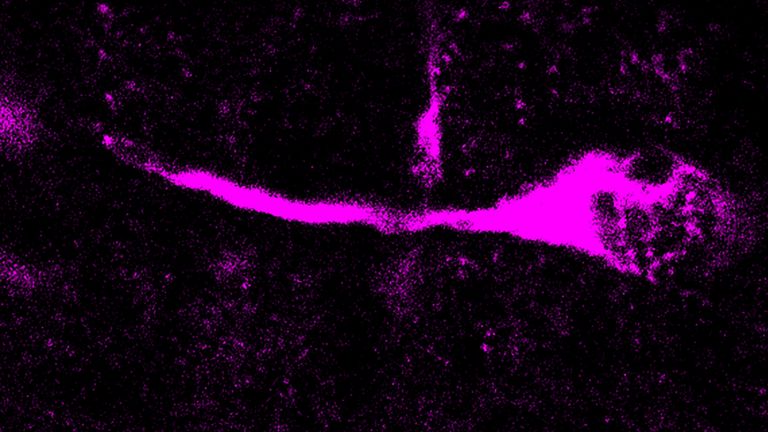

In order for the tennis player to finally close their fingers tightly around the ball, throw it up, tense their muscles, and swing for the serve, the movement plan must reach the muscles. This happens via pathways that originate in the primary motor cortex and then travel down the spinal cord. These pathways enable the brain to communicate with the motor neurons in the spinal cord, which are connected to specific muscles and muscle groups via their axons. The spinal motor neurons then trigger the movement by activating the muscle cells. The tennis player serves, the opponent makes a good return, and the rally continues.

Practice makes perfect

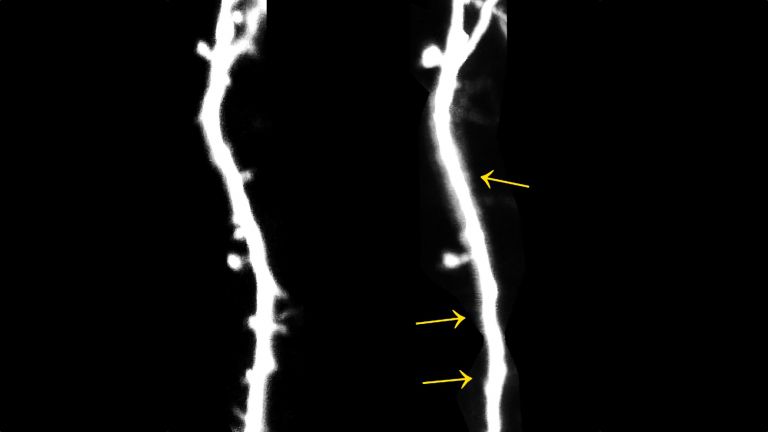

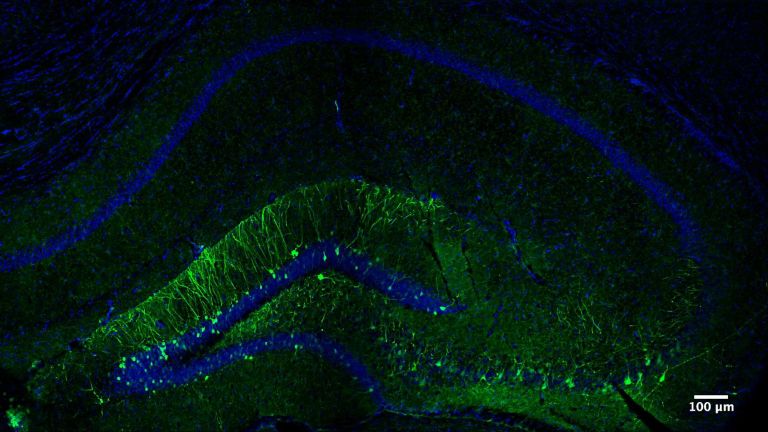

Some movements are rather large, such as rowing with your arms. Others, such as writing with a pen, are precisely coordinated and finely modulated. The fine motor skills required for a movement depend, among other things, on the number and control of the lower motor neurons in the spinal cord. If many lower motor neurons can be directly controlled for the movement of a muscle group, this movement can be performed more finely. The best example of this are the fingers, which are equipped with numerous small muscles and a corresponding number of these controlling motor neurons. However, those who engage intensively with a sequence of movements – i.e., practice a lot – can also influence the fine tuning: musicians, for example, can coordinate the motor skills of their fingers, hands, and arms particularly well, while athletes such as our tennis player can coordinate their strength.

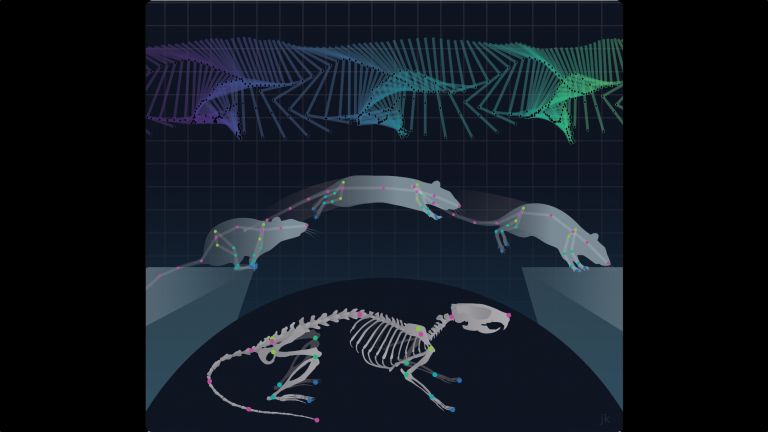

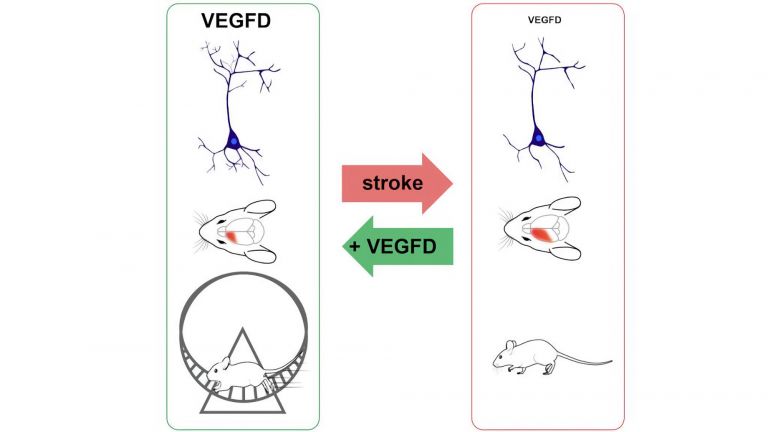

Studies on rats suggest that this ability to learn motor skills is also based on a reorganization of the neural networks in the primary motor cortex. If groups of nerve cells that were actually reserved for a particular movement are used infrequently, they can apparently be retrained to control other movements. This property is exploited in rehabilitation after brain damage: if a patient has lost certain motor skills after an accident or stroke, they can relearn them to a certain extent with a lot of practice and patience. For those affected, this is an enormous gain in quality of life, even if playing tennis is usually no longer possible.

First published on August 31, 2011

Last updated on December 1, 2025