Command Center for Movement

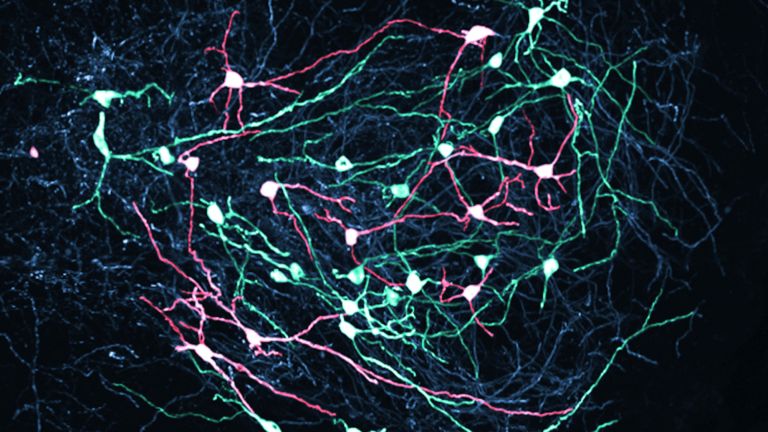

The primary motor cortex triggers movement. That much is certain. But beyond that, this part of the cerebral cortex – despite 150 years of research – continues to pose new puzzles for science. This is because its structure is more complex than initially thought.

Scientific support: Prof. Dr. Hansjörg Scherberger

Published: 01.12.2025

Difficulty: intermediate

- The primary motor cortex controls the spatial-temporal sequence of movements. Its neurons are largely the starting point for the pyramidal tract.

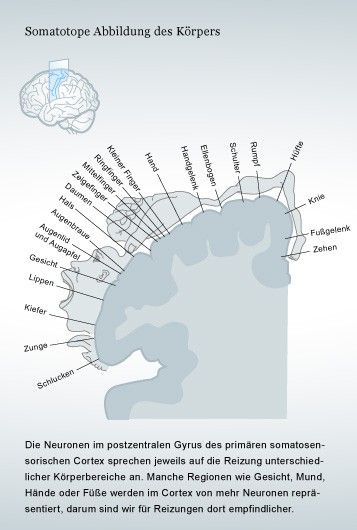

- Certain areas of the primary motor cortex are responsible for specific parts of the body. The hands and tongue are disproportionately strongly represented.

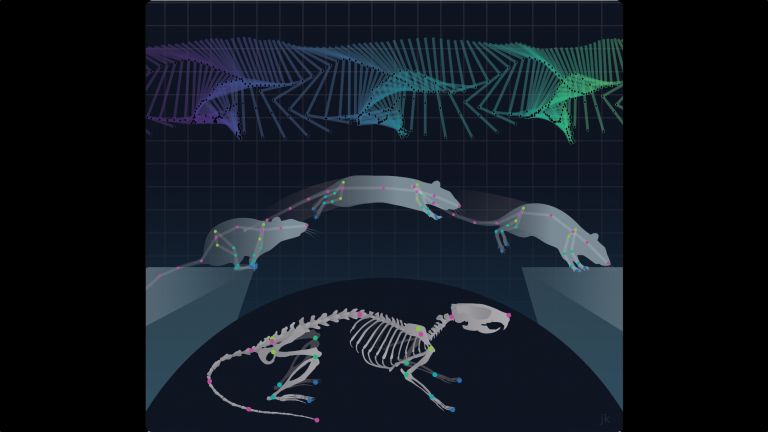

- Recent studies have shown that it is not individual muscles that are represented, but rather movements themselves, such as raising the hand to the mouth and opening the mouth at the same time.

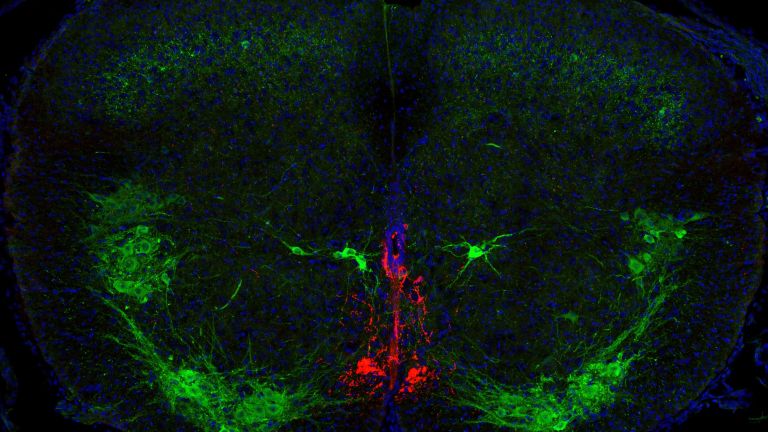

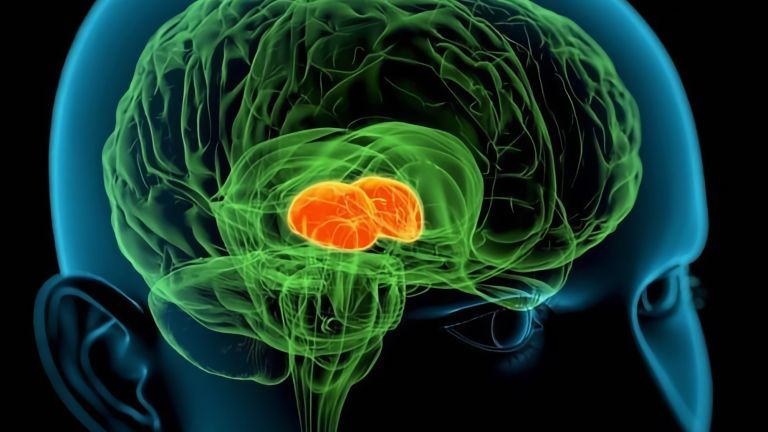

Shortly before a movement, such as reaching for a glass, increased activity can be measured in many regions of the brain. However, this activity is then concentrated in an area of the cerebral cortex in front of the central sulcus, the central groove between the frontal and parietal lobes of the brain. This is where the primary motor cortex is located: it is about two centimeters wide and is largely hidden in the central sulcus. The neural signals that command the muscles to contract originate mainly here.

Starting signal for movements

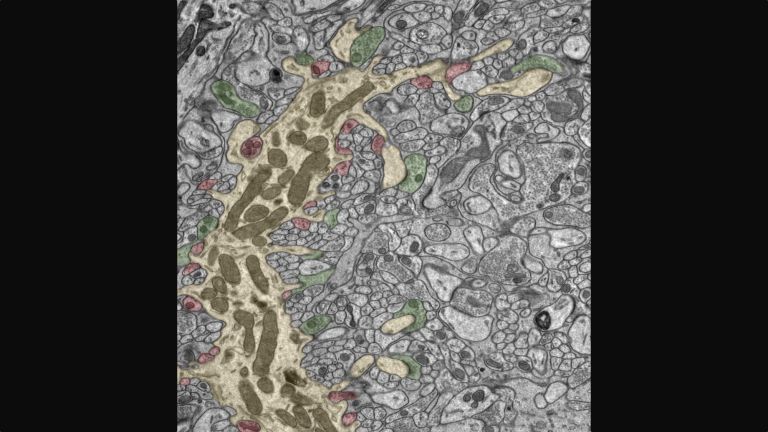

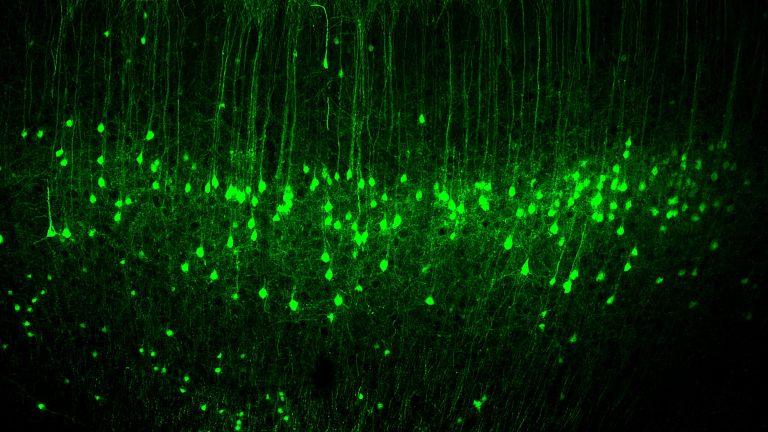

The primary motor cortex is the starting point for large parts of the pyramidal tract, which, with a million axons, is one of the longest and largest tracts in our central nervous system. This is where nerve cell extensions originate, which travel uninterrupted through the brain stem and on to the spinal cord, from where they then transmit commands to the muscles via so-called motor neurons.

It has been known for over 140 years that muscle contractions can be triggered by electrical stimulation of the primary motor cortex. This can also be achieved by stimulating other areas of the brain, but only with greater force, i.e., a higher current. The primary motor cortex does not have a monopoly on movement, but it is clearly the main player and market leader. Damage to this area of the brain, for example due to a stroke, results in paralysis.

However, the decision to stretch one muscle and bend another at the same time is mainly made by other areas of the brain: the premotor and supplementary motor cortices plan and initiate movements and complex movement patterns – the motor cortex is also involved in decision-making, but plays a subordinate role. These areas of the brain are therefore intensively interconnected with the primary motor cortex. Once the decision to move has been made, the primary motor cortex takes over: it ultimately gives the starting signal for a movement. However, its neurons also fire in anticipation of a movement, for example when a sprinter is waiting for the signal to start running. This allows the runner to move faster when the starting signal sounds. Even when we just imagine throwing a ball, the primary motor cortex is active. However, the excitation is then lower than when we actually perform this movement.

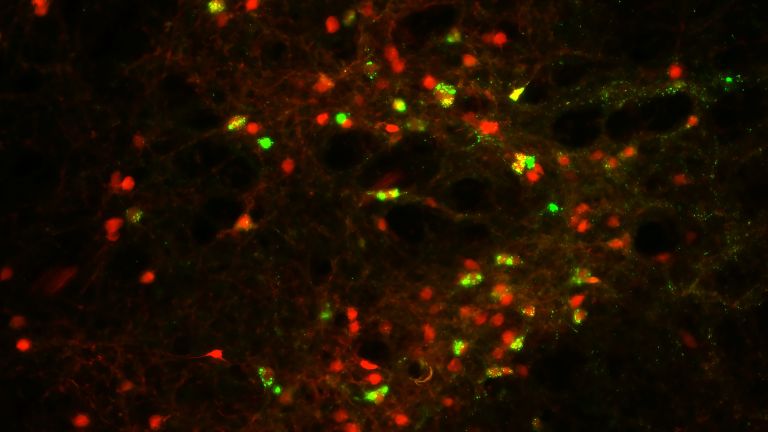

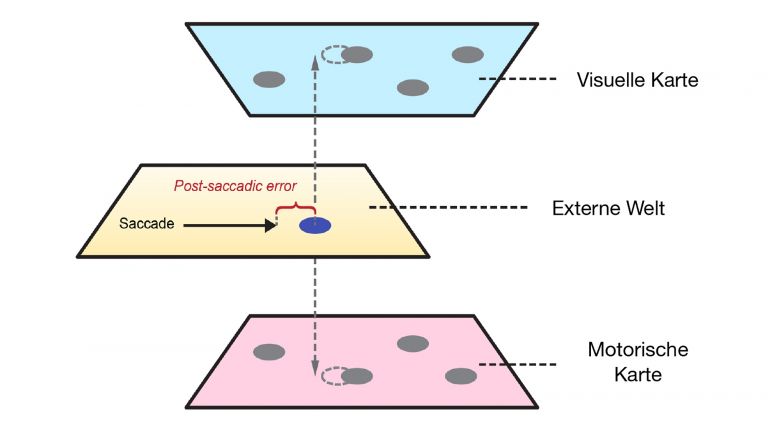

But movement is not a one-way street: it is not set in motion only to then proceed without correction. The somatosensory cortex uses proprioceptors to register parameters such as the position of individual body parts, joint position, and muscle tension, and continuously exchanges information with the primary motor cortex. The command center, as well as subcortical control centers such as the cerebellum, thus receive constant feedback on a movement sequence and can make corrections if necessary.

The cartographer of the human brain

It has been known since the end of the 19th century that a specific area of the brain is responsible for triggering movements. In 1870, German brain researchers Gustav Fritsch (1838–1927) and Eduard Hitzig (1838–1907) electrically stimulated the motor cortex of dogs, causing the animals to move the legs on the opposite side of their bodies.

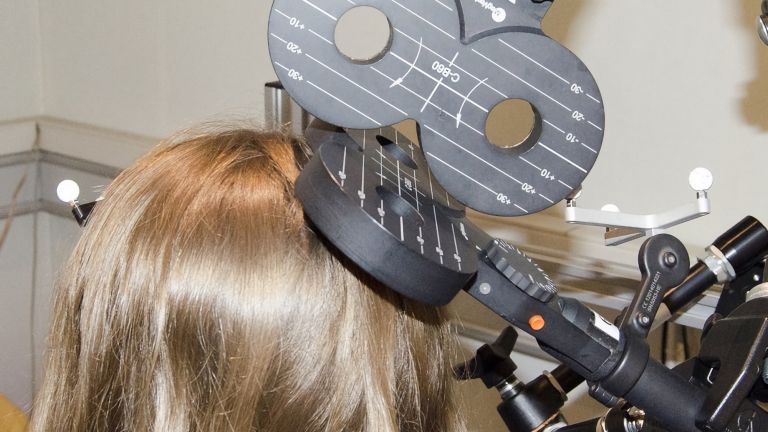

A few decades later, Canadian neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield (1891–1976) took a much more in-depth look at the motor cortex – not on laboratory animals, but on humans. "In the course of operations on the brain, I have stumbled on some fascinating findings. I must confess that it was usually more by accident than by design," he reported in 1961, when the Royal College of Surgeons of England awarded him the Lister Medal for his outstanding achievements in surgery. Penfield operated on seriously ill epilepsy patients, removing, for example, tumors in their brains that were causing the symptoms.

These procedures were tricky: Penfield had to find exactly the right area to remove. If he was wrong, the patient might end up paralyzed or unable to speak. Therefore, before each operation, he made sure he knew which part of the brain was responsible for which function. He lightly anesthetized his patients but kept them conscious while he opened their skulls and carefully stimulated the brain around the affected area with platinum electrodes. He observed the patient closely and asked them to report what they felt: if he touched parts of the somatosensory cortex, the patient felt as if someone had stroked their cheek, for example. If the motor cortex was stimulated, a specific part of the body moved. Penfield made precise notes on which area was responsible for which part of the body.

Penfield operated on around 400 patients in this way. The result: a map of the primary motor cortex showing which area was responsible for which part of the body. Such brain maps became known as homunculus, Latin for “little man.” If you draw how the human body is represented on the two-dimensional surface of the motor cortex, you get a grotesquely distorted little man with huge hands and a disproportionately large tongue. This shows that it is not the size of a body part that determines how strongly it is represented on the motor cortex, but the extent of its fine motor skills. The hands can perform particularly difficult movements, as can the tongue in humans, because this is important for speaking. Therefore, these body parts are strongly represented in the motor cortex. The motor homunculus lies virtually on the surface of the brain: it begins in the middle of the brain with the toes, bends at the central sulcus, and ends at the side with the head, with the areas for the tongue and larynx located at the very edge.

Recommended articles

Not individual muscles, but complete movement sequences

Penfield's homunculus may give the impression that there is a precisely defined area of nerve cells on the cerebral cortex that is responsible for a specific muscle in the middle finger, for example. The area next to it would then be responsible for another muscle in the middle finger, and an area further away would activate the same muscle in the ring finger, and so on. However, this theory, which had long been assumed by scientists, proved to be false. Today we know that the motor cortex does not function in such a simple and schematic way.

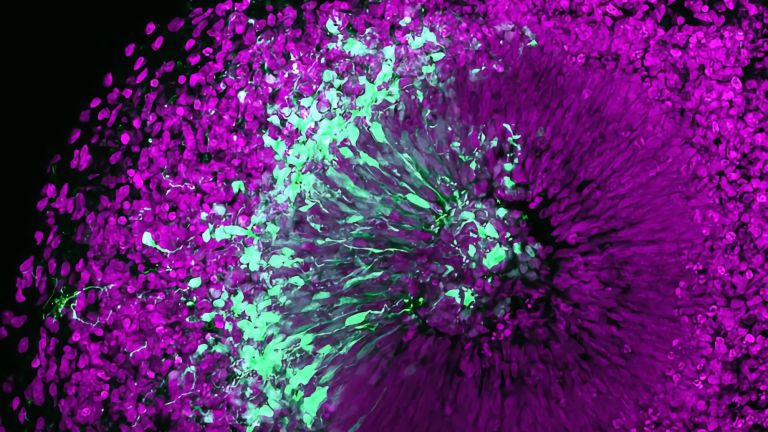

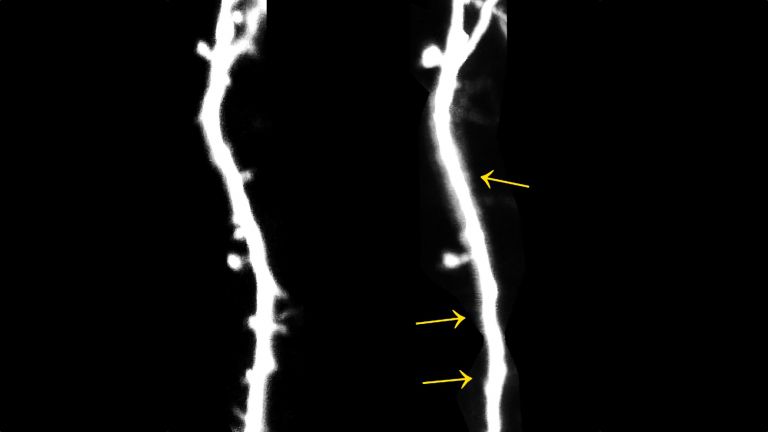

The areas of the brain that are active during simple flexion and extension of the first three fingers overlap to a large extent. Nerve cells that can stimulate a specific muscle are all located within a certain area, but they are usually spread over a relatively large surface of the cortex and are not crowded together in a narrowly defined area. A small section of the primary motor cortex therefore influences quite a large number of muscles.

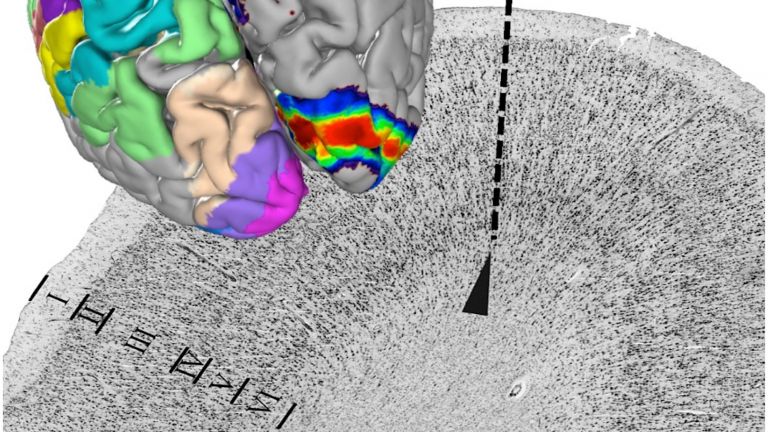

Representation of movement categories in the primary motor cortex

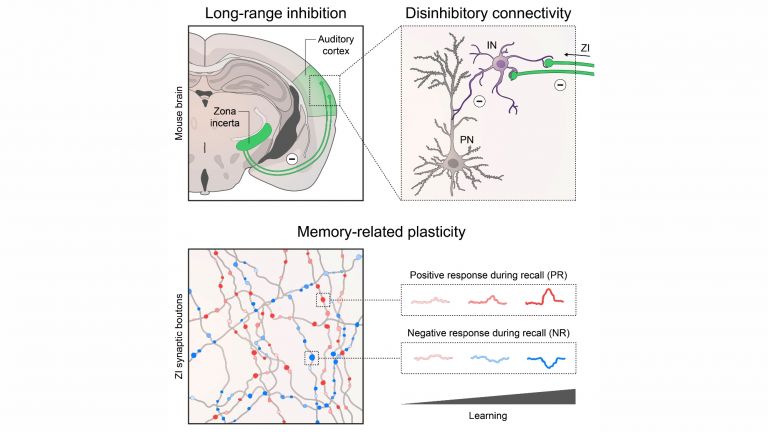

In 1999, a research group at the Health Science Center of the State University of New York in Syracuse, USA, studied the motor cortex of monkeys performing various hand and arm movements. A small portion of the neurons in the monkey's brain actually changed their activity depending on the muscles the animal used during a movement. However, the vast majority of nerve cells seemed to be responsible for different types of movements: depending on the direction in which the monkey moved its wrist, these nerve cells fired with varying intensity, regardless of the individual muscles that were in action.

Research by other scientists also points in this direction: it is not individual muscles, but rather categories of movement that are represented in the primary motor cortex. For example, researchers led by Michael Graziano at Princeton University in the US were able to trigger specific movement sequences involving different parts of the body by selectively stimulating areas of the cortex – such as closing the hand to grasp, then moving the hand to the mouth, and opening the mouth at the same time.

When the scientists stimulated another region, they caused the face to contort, the head to turn in one direction, and the arm to shoot up as if to protect the face from a blow. Michael Graziano was also able to show that prolonged stimulation of a region triggers more complex motor actions. To date, scientists have not been able to decipher in detail exactly how such movement sequences are controlled by the primary motor cortex and encoded in the nerve cell networks there. Even almost 150 years after its discovery, the command center for movement still poses many mysteries for researchers.

With its billions of nerve cells, the brain is by no means a rigid structure, but rather one that is constantly changing – throughout a person's entire life. This is especially true of the primary motor cortex. In a pianist, this part of the cerebral cortex is organized very differently than in a construction worker: through regular practice, the area of the motor cortex that represents the trained body part becomes larger. And after an amputation, the area that was previously responsible for this body part is partially repurposed and then takes on other tasks. Thus, at least one thing is certain about the primary motor cortex: it is unlikely that two people will be found who have the same structure in this important area of the brain.

First published on August 28, 2011

Last updated on December 1, 2025